8: Locating the stations

<< 7: Designing the ticket system || 9: Designing the train schedules >>

The De Leuw Cather report to MTARTS discussed the need for short journey times in the rail

commuter service, and the importance of feeder services by private automobile and by city bus.

The quality of the proposed service depended upon being able to attract commuters out of their

cars, to park their cars at the stations, and ride the trains instead. It put forward the case for not

having station stops too close together. The recommended criterion was that the spacing between

station stops should be not less than two miles. So the proposal that was accepted, to reduce the

number of station stops that the present commuter trains were making, by consolidating certain

stops into a single stop, and cutting out some others altogether. The approximate locations for

the stations were given in the MTARTS report. On the east end, the only existing stop was where

CN's intercity trains made a suburban stop at Danforth, and where the only commuter train to

Uxbridge made a stop at Scarborough, so new stations were proposed. These also were to

conform to the concept of not being too close together.

Starting from Dunbarton, there would be five intermediate stops from there to Union Station,

and from Oakville, four. There was still some question in our minds about the report's

recommendation to eliminate the existing stop at Sunnyside, so we held in reserve the possibility

of a fifth stop on the Oakville side. The report was broadly specific as to the suggested locations

for the stations, but did leave some flexibility in the final choice of site.

For a commuter station to serve an area wider than just for passengers walking in, good

access by roadway and adequate parking space would be essential. So station sites had to be

finalized, based on these criteria. In most cases, this demanded that the site should be at an

important road crossing, where buses could feed the passengers to the trains, where automobile

drivers could drive from development areas well away from the line, and where there were open

lands that could be developed for parking, easy to get to from the road.

The study on main line capacity had already determined that the reversing tracks at the outer

terminals should be on sidetracks, so that the trains standing for ten minutes to change ends

would not be occupying time on the main line. An understanding between CN and the

Government of Ontario was that the outer ends of the new commuter service would not extend

into the territories where the main line freight trains would be operating in and out of the hump

yard. On the east end, the hump yard access line came in at a junction under the overpass at

Liverpool Road, so it proposed to terminate at Dunbarton, and should not go through the

overpass at Liverpool Road. By terminating on the west end at Oakville, this avoided any

conflict with the access line.

The responsible members of the commuter group started out to examine locations along the

length of the line to identify possible station sites that we could then put to the Government for

final selection.

Dunbarton becomes Pickering

At Dunbarton, the intended roadway access was to be from the north and south by Liverpool

Road, where the existing overpass crosses the main line. We had been instructed not to run the

commuter trains beyond the Liverpool Road overpass, because that would interfere with the

freight trains coming off the access line. Our visit to the site immediately showed us a problem.

The only space available to put a terminal station lay quite a distance west of Liverpool Road,

between the CN main line, the freight access line and highway 401. On the side of the freight

line and highway 401, there was no way passengers would be able to get to a terminal station.

On the other side where the tracks were on a high fill, was a four-lane roadway called "Bayly",

deeply below the level of the main line. The only open lands that might be an area for

automobile parking would require all passengers to cross to the far side of the road. The only

way out for passengers, from where the station would have to be, was through a narrow stone

arch under the railway fill that had been the route of an important country road. This is the road

that used to connect with what is now Dixie Road in Dunbarton, before the construction of

highway 401 cut it off completely.

We walked back along the tracks all the way to Whites

Road, but the problem was the same all the way, and

Whites Road was a long way from the intended end point

of the service. On the east side of Liverpool Road we

found an open field, between the tracks and Bayly Road,

that could accommodate an excellent terminal station, if

only our trains could get through the underpass.

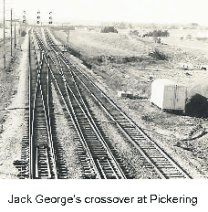

The Accountant, Jack George, lived in West Hill, and

he came into the office one day, saying he was sure we

could find space for a parallel crossover before the

overpass at Liverpool Road. This would let our trains

reach the industrial track beside the open field, without

conflicting with the freight trains coming out of the yard.

Then we could put the terminal platform beside the field, and the trains at the platform would be

standing off the main line. So Harry Kier took out his drawings and visited the site, confirming

that it could be done. He got concurrence in CN, so now we could take it to the Government.

The Government would be responsible for

the roadway access, so we invited them to

visit the site with us. We met Bill Howard

and Ed Ingraham there to discuss this new

possibility. The field would lend itself well

the station buildings, the parking lots, and

for a parking lot at a terminal station, but

there was a gas station in the upper corner.

We could not persuade them that the whole

field would be needed, so they took only

about one quarter of the field, and left the

rest for a later date.

Another complication arose. Bill came

back to us to say that now that the station

was to be on the east side of Liverpool Road, it would not be in Dunbarton, but instead would be

in Pickering, so could we please give it the new name? That also had to pass up to CN

Headquarters in Montreal, where a problem showed up again. There was an order office and

station out at the switch where the freight trains entered the mainline that already had the name

Pickering, so that would have to be changed to release the name to us. The name was not

released to us officially until CN's next working timetable became effective, with a changed

name on the order office, but we began to use the name unofficially right away.

Rouge Hill

CN had a small yard at the foot of Port Union Road, where helper engines used to wait for

freight trains coming from the east, to couple on and help them up the grade to the summit at

Scarborough. So there was an order office there that had been used to give train orders to the

helper crews. The order office and the short locomotive tracks in the yard were out of use, since

the helper engines were long gone. This land could have been available for a commuter station,

so the report had used this to offer a station in the same location, by the name of "Port Union".

When our inspection party arrived on site, we saw that there was not enough available land

for parking. The road itself came to a dead end, so automobiles coming to the station would have

to go out again against the flow of more cars coming in.

But just 500m to the east the tracks touched Lawrence Avenue, a principal east-west roadway

that, at that time, did not extend further east except as an unpaved cart track. There was also a

north-south road, East Avenue, West Hill. There was an open triangle of land that could serve

for parking and for a bus turning loop, once bus service was extended to that point. So the

decision was made to place the station where the tracks ran close to Lawrence Avenue, and make

the access to the station directly from the Lawrence.

At the east end of where the platforms would be there was a grade crossing. This crossing had

some complications with it. It was officially a farm crossing, with no real legal status, so there

were no precedents for putting grade crossing protection devices on it. Also, it would be only a

short distance from the end of the platform at the station. If we concluded that it would have to

have protection installed, then a train making its station stop would hold down the barriers for

the duration of the stop. Grade crossing protection is obligated to be in operation at least twenty

seconds before the train reaches the crossing. The intercity trains and the long freight trains that

would be passing there at high speed would have to activate the protection while they were at

least twenty seconds away.

Clearly, this mix of high speed and stopping trains passing on the tracks meant that some

form of protection had to be installed, so the decision was to solve the problem in another way.

The protection is activated by all trains approaching, while still the standard distance away, but if

the train stops at the station, then the protection de-activates, and allows road traffic to cross.

Then, when the train restarts, it must approach the crossing very slowly, until the protection

restarts, then it proceeds as usual.

This was the site chosen for the Premier of Ontario, the Rt. Hon. John Robarts, to drive a

bulldozer to turn the first sod, when construction of the commuter service started. A small group

of school children watched the short ceremony, but it was all rather low key. The news reporters

complained they had inadequate notice, so mostly they were absent.

Guildwood

The intent of putting a station at Guildwood was to afford connections to the TTC buses along

the Kingston Road, as well as access for automobiles using that road to reach the station. It

would have been best if the pedestrian access

to the station could have been directly from

the

Kingston Road overpass, where there was an

adjacent bus stop. Unfortunately, the land

close to the overpass was occupied by a long-

established lumberyard. In view of the

philosophy that this was only a

demonstration, at limited investment cost,

and perhaps with a limited life, there was no

possibility of taking over this yard, so we had

to look at the next open lands slightly away

from the Kingston Road towards the east.

Eglinton

The site proposed for a station at Eglinton was based on the existence of public transit along

Eglinton Avenue, and the availability of land for parking. Automobile drivers from the north

could come south on Bellamy or the Markham Road, so a convenient parking lot would be on

the north side of Eglinton.

Bob Schmidt had some misgivings about this. The

counts he forecast for the origins of potential riders

showed many people coming south on the

Markham Road, and he worried about putting all

this extra traffic on Eglinton Avenue to reach the

station. We walked the railway tracks at the

Markham Road to see whether the station might be

there, but the tracks are in a cut under the overpass,

there was no space for parking, and the adjacent

lands were already committed for high rise

development. So the station was built at Eglinton.

There was land available for a relatively small parking lot on the north side of the road, and

passengers to and from there would have to cross the busy Eglinton Avenue at the traffic light at

the intersection with McCowan, a short walk to the west. For a later date, when funds would be

available, we suggested it might be possible to hang a pedestrian walkway on the side of the

railway overpass, so that passengers could walk to the north parking without descending to the

sidewalk. This need disappeared when much larger parking space was developed on the south

side of the tracks, so that passengers would not need to cross the road.

Scarborough

There was an important railway junction at Scarborough, where the tracks of the Uxbridge

Subdivision connected from the north, so CN had an office there, by the name of Scarborough

Junction. Also, the one and only commuter train operated by CN on the east end was one trip a

day to Uxbridge in the outward direction only, so it already made station stops at Danforth and

Scarborough. The Uxbridge Subdivision crossed St. Clair Avenue, but did not cross Midland

Avenue, so the station had to be on the south side of St. Clair Avenue.

There was another complication. The junction was close to the grade crossings of St. Clair

Avenue in the east-west direction and Midland Avenue in the north-south direction. These

crossings were obvious candidates for grade separation at some time in the future, but the

expense and the time involved for such a complicated project clearly prevented us from

expecting this to happen in less than two years, when the service should start.

The inspection on site showed that the station would need two separate platforms, one

between the north main line and the Uxbridge Subdivision branch line, and the other beside the

south main line. There was land available for parking on the south side of the station, and the

presence of the branch line discouraged any thought of looking on the north side. This was the

one station where we planned that the access to the ends of the station platforms would be by

direct walk-in from the sidewalk of St. Clair Avenue, separately to each platform, so we needed

two ticket booths, one for each. Passengers from the parking lot walked first out to the street,

then along the sidewalk to the platform entrances. This situation persisted until the grade

separations were put in, at a much later date.

Danforth

There was a long-established station at Danforth, from

the days when that was an outer suburb on the east side of

Toronto. Most of the intercity trains made a station stop

there, as did the Uxbridge commuter. The station was in

the shadow of the overpass that carries Main Street over

the tracks, and the existing platforms passed under the

overpass in a constricted manner. With a streetcar service

on the overpass, and Danforth Main Street close by, it

remained a good choice for a commuter station. The

existing station was a short distance from Main Street, to

allow a driveway from the street for taxis, and other road

vehicles. This layout made the walk from the street to be

longer than a good commuter service justified, so the plan

was made to locate the new ticket booth close to the overpass. Being in the inner city, this was

the only station where there was no intention to provide parking.

The criterion for platforms of the new service was a width of at least 10ft (3m), except that

the ends could taper down somewhat. To meet this, it was best that the platforms should start

only at the overpass, and extend eastward for the full length of 850ft (255m). This allowed space

under the overpass, where the old platforms had been, to put a pedestrian walkway for

passengers to walk to the other side of Main Street. This had to be at an intermediate level, so the

ticket booth also was raised to the same level, with stairways to reach the sidewalks above on

both sides of Main Street. Since passengers would be coming from the Main Street overpass

above, it was logical to use a pedestrian overpass to cross the tracks, so Danforth is a station

where no underpass was put under the tracks.

At the same time that the commuter service was being planned, the TTC was advancing plans

for the construction of the Bloor Subway line, that was to follow under Danforth Main, a short

distance north from the CN tracks. It would have been an advantage, if we could have had a

convenient interchange station between the two lines. Since the CN line offered no possibility of

relocation to come closer to Danforth Main, we discussed with the TTC whether the alignment

of the subway could be diverted to come close to the CN tracks. Unfortunately it was already too

late, and the designs were already committed. Passengers arriving from east or west at the

Danforth station now have to walk about 300m to reach the Bloor line subway station.

Union Station

At the time the MTARTS report was prepared, the understanding had been to assign only a

single track for the new service at Union Station. The track designated was #13, at the far south

end of the passenger concourse. The decision to use on-ground ticketing meant that ticket sales

and collection would be occupying space in the concourse, where intercity passengers would

walk through to access tracks 11 and 12. This was at the same time that the Tempo trains were

already on order, and CN was promoting new concepts in intercity passenger services, with a

new fare structure, based on "Red, White, and Blue" days.

The General Manager, Passenger Sales, Garth Campbell, came down from CN headquarters

in Montreal, to examine the plans, and had an immediate negative reaction. He had full

experience of how commuter services could grow in the end, and he did not wish to envisage

heavy flows of commuters walking the whole length of the concourse to reach their trains. There

would be too much potential conflict with passengers with their baggage circulating in the

concourse to access trains on the other tracks.

The Union Station was designed with a large hall having an upper and a lower floor, facing

on to Front Street. The upper hall was devoted to departing passengers, with ticket sales

windows, redcap services, a checked baggage counter, and some small boutiques. To reach the

trains, passengers walked down a gentle slope into the departure concourse under the rail tracks

in the train shed. There were stairways leading up from each side of the concourse to the

departure tracks above. The departure concourse had corridors on each side at the same level that

were used for arriving passengers. The platforms had another pair of stairways, one on each side,

for arriving passengers to descend to the side corridors. These corridors were on the same level

as the departure concourse, but they connected into the lower level of the hall on a ramp down.

This was the arrivals level below the ticket hall, where people could await the arrival of the

passengers coming off the trains. This achieved separation of inward and outward passengers,

and avoided conflicts in the flows of people movement.

Garth proposed to adapt this layout for the commuter services. He proposed to put both

inward and outward intercity passengers into the upper hall, release the lower hall to the

commuter traffic, and to assign the tracks and the passenger platform between tracks 2 and 3 to

the commuter trains. The stairways down from the commuter platform to the departure

concourse were closed off, and arriving commuters came down into the side corridors. Walls

were erected in the side corridors, beyond tracks 2 and 3, so that the commuters would not move

into the intercity spaces.

The space in the lower hall, where people had waited for arriving passengers, became

available to put the ticket collection barriers, and the newsstand in the centre became the ticket

selling office. Commuters leaving or arriving passed each way through the same barriers, and

along the same corridors and stairways to the platform. In the interests of economy in the

beginning, there were no information signs on the platform, so the train crews used the loud

speakers on the outsides of the trains to tell passengers on the platform where that train was

going.

Mimico

The location of the new commuter station for Mimico has been discussed in the chapter

"Inventing Willowbrook". The site could not be in the same location as the CN Mimico station,

because the layout of the Willowbrook service depot needed to have a re-arrangement of the

tracks into the yard.

Long Branch

The MTARTS report proposed that the existing stations at Long Branch, Dixie Road and the

Lakeview station at Cawthra Road should be consolidated into a single station. To do this, the

CN station called "Long Branch" should be moved slightly to the west, where it would make a

good interchange with the TTC loop, that is the outer terminus of the streetcar line along

Lakeshore Road.

An option was considered to place it at the

foot of Browns Line, where there was land

available for parking. This location offered

direct access for automobiles from the north,

and still was close to the streetcar line.

Inspection on site showed that the tracks were

in a cut as they passed under Browns Line.

Creating a station there would require

considerable excavation and disruption of

adjacent developed lands. The proposal

implied more expense than was warranted for

the commuter concept that was still regarded

as a three-year demonstration.

Quite separately, CN was committed in the project replacing the grade crossing with a grade

separation at Dixie Road, where there was a commuter train station. Engineering designs for this

separation were well advanced, including platforms on both sides of the tracks, and access

stairways from both sides of Dixie Road. The plans were put to the commuter group for

approval, at the same time as the location for the Long Branch station was under study, so there

was some urgency to finalise the planning.

The streetcar turning loop is about midway between interchanges where Browns Line and

Dixie Road make the junctions with the Lakeshore Road. Automobiles could arrive easily

enough from the north by both roads, and eliminating the flat crossing of the railway tracks at

Dixie Road would enhance the usefulness of that road. The problem there was a marked lack of

open lands for parking, so this was a location where residential properties would have to be

taken over to create parking space. It was accepted that this was the best compromise, and the

next steps would be to start the detail design of a new station at the turning loop.

The plans for the grade separation at Dixie Road were returned with the message that the

platforms and stairways could be eliminated,

and the total cost reduced accordingly.

It was Harry Kier's job to prepare the final

layout for the station at the Long Branch

turning loop. We wanted to make the exit

from the station to be directly opposite the

loop, so that the interchange would involve

only a short walking distance. There were two

limitations. The decision to locate the station

there required that a row of houses between

the tracks and the turning loop would have to

be expropriated, demolished, and resurfaced

to create a parking lot. This would use time

that could delay the construction and opening

of the station. Even after that area would be

cleared, there was a substation for the streetcars that prevented a direct walk across, so

passengers interchanging would have to walk behind the building and then around the loop. So

Harry was forced to plan to put the station further down the hill towards the creek. It created a

reasonably good interchange, but one not as convenient as we would have preferred.

Port Credit; political battle keep a station at Lorne Park

There was an existing station at Port Credit, where some of the intercity trains had made stops

in the past, but now were passing by without stopping. However, the station was at the foot of

highway 10, a location that had attractions for developers of residential properties, and already a

few commuters were driving down to park in the streets to take the commuter train. The choice

to continue with the commuter service at that station was not in question.

There was a political complication, in that, in the recommendation to achieve faster train

operations by ensuring adequate distances between station stops, the MTARTS study had

recommended that the station stop on Stavebank Road at Lorne Park, three kilometres to the

west, should be consolidated with Port Credit. Residents at Lorne Park wishing to access the new

commuter service would go to either Clarkson or Port Credit.

The residential development at Lorne Park consisted of relatively high value properties, so the

owners and occupiers objected strenuously to the closure of their station.

This created an ambivalent attitude on the part of the public. Clearly, a new and frequent

commuter service was a good objective. To achieve the performance needed, stations would

have to be far enough apart, so that journey times could be short enough to be attractive

compared with driving to work. So they could recognise the need to close stations, but, please,

not our station! A protest group came together and they called upon the town councilors to lead

the opposition. The Mayor, Bob Speck, tried to negotiate with CN and the Government, to

continue with the station stop there. A public meeting was set up, where the positions of all the

pros and cons were laid out. The man in the middle was Lou Parsons. He was the elected

representative for Ward #2 in Lorne Park, so he represented the town at the public meeting.

It was a difficult meeting. It fell to Bill Howard to present the Government side. I was called

upon to describe the quality of service we

would be operating, and how important it

was to not retain the Lorne Park stop. Norm

Hanks gave an exposition on the

impossibility of making more station stops,

if there was to be adequate capacity on the

line for the new train service to operate at

all. The hall was full to overflowing. There

were several occasions when we, as the

speakers on the platform, had to walk away

from the microphone, until Bill Howard, as

the M.C., could allow us to be heard again.

It was a raucous meeting and the audience

was hostile throughout.

The message got through to Government, that Lorne Park needed some recognition of their

problem. We could not add an additional station, so they asked us if we could make the best train

of the day serve Lorne Park instead of Clarkson. The concession was made that the first

timetable would include this arrangement. It created a problem for the ticket collection system.

We could not justify building a complete station, and assigning on-ground ticket collectors, for

one train in a morning and one train in the evening, five days a week. Our solution was that, after

the previous train had passed Clarkson, the ticket takers from there would take a taxi to Lorne

Park, collect the tickets there for the next train, then taxi back to Clarkson for the following train.

This arrangement persisted for the first two years of operation. Then it became clear to the

users, that the full service at Port Credit was superior to one train a day at Lorne Park, and there

was some unhappiness at Clarkson, when the best train of the day did not stop there. The

Government accepted that we should terminate the arrangement. So the last train to stop at Lorne

Park was a GO-Transit train, two years after the service was inaugurated.

Clarkson

The CN station at Clarkson was at Clarkson Road, in the heart of the town. This location

dated from the days when it was only a village, where trains stopped to serve the local

community and the holders of the summer cottages on the lakefront. On one side were rail tracks

serving local industries, and it was surrounded by lands already developed for other uses, so

there was no space for parking, and access would have been through those congested streets.

About 400m to the west, there was a grade crossing where the tracks met Ontario highway #1,

as it was then. Long range planning included building a grade separation there at some time in

the future, but it was not yet in the design stages. This was an opportunity to develop an

excellent north-south access route that also offered good access from the west along the

Lakeshore Road. The site both to the north and south of the tracks had large open lands that

could become adjacent parking areas.

The Government representatives and the commuter group had no hesitation in deciding this

should be the location for the new Clarkson Station. Bill Howard took it back to the Department

of Highways to work with the CN Engineering Department to accelerate the construction of the

grade separation, and we went on to design the station that would be built there.

Oakville

Oakville was a town of sufficient importance that

most of CN's intercity trains made a station stop there,

as well as the two commuter trains from Hamilton. A

service of that calibre naturally had already induced

development of the whole community as a satellite

city, 21 miles from downtown Toronto. There was a

recently modernized station building, and an adjacent

holding shed for the Express Department. The design

followed the tradition of an open and unfenced station,

where the two tracks of the main line were served from the north side. The platform for the south

track lay between the tracks, so that passengers using that platform had to walk across the north

track to reach the station building.

There were three counts why the station as it stood could not meet the criteria of the new

commuter service. Commuter trains reversing at Oakville could not block the main line for that

length of time. The south track would have to be separated with a fence so that passengers would

not walk across the tracks, so that rule 107 would not apply there. The north platform did not

lend itself to being fenced in for on-ground ticket collection.

On the south side of the two main lines, and a little distance from them, there was a team

track that was now almost unused. A team track was a place with roadway access to the track,

where clients, who did not have their own industrial sidings, could bring their vehicles alongside

a freight car, and transship their commodities into road vehicles. The team track in Oakville had

handled a lot of freight traffic in the past, but now traffic was almost zero.

We took the matter up with Bob Doty, who was the Freight Sales Manager for the Area. He

arranged to handle the remaining team-track work at another location to release the team track

for us to use as the terminal track for the commuter trains. The lands available for parking were

all on the north side, around the station house, which

required a pedestrian underpass under the main lines,

for commuters to reach that commuter platform. The

intercity trains still required a platform accessible on

the south track, so Harry Kier designed the

commuter platform between the south track and the

erstwhile team track. As it lay, the track was too

close to the south main line, so it had to be moved

further away to make space for the platform to be

put in. The booth for the ticket control was placed at

the north portal of the underpass. Intercity trains

would make station stops at the south platform.

Access to this platform would be through the

underpass between the platform and the station, so ticket takers at the control booth needed to

allow passengers to pass when they were holding intercity tickets.

There was still another complication. There would be two commuter trains each way on

weekdays running beyond Oakville to Hamilton. In most cases, these trains were directed by the

dispatchers to pass through the commuter track, even though they continued back on to the main

line. This was not always possible. When the dispatcher had to put the Hamilton trains through

the north track, the open platform made ticket collection somewhat difficult. Commuters quickly

recognised the purpose of the on-ground

system, so generally they handed their

tickets to the ticket takers, upon leaving.

Bronte, Burlington, and Hamilton.

The effect of introducing the new

service was slight at these stations. There

would be two trains to Toronto on weekday

mornings and two from Toronto to

Hamilton in the evenings. There had been

equivalent service with the CN trains, so

the only change was the introduction of

new train equipment, and a minor

speeding-up of the timetable. The Station

Agent collected the tickets on the platform,

and submitted his reports as usual.

<< 7: Designing the ticket system || 9: Designing the train schedules >>