Review Notes on Western and Central Europe, 475 CE – 1648 CE

In general, European history from 475 CE to 1648 CE has been taught from the perspective

of Western and Central Europe with a tendency to see its culture as primarily Roman

Catholic Christianity and its 16th century offshoots. Some of this can be

explained by the adoption of Hellenistic culture and the desert religion, Christianity, by

the Romans and the expansion of the Roman Empire outside of the Mediterranean Basin. Part

of it is explained by literacy; history of written from documents and societies that

don’t produce documents (or too few) don’t have their own histories. Someone

else might mention them, giving us reason to believe they existed and, perhaps, even some

knowledge of what those people did.

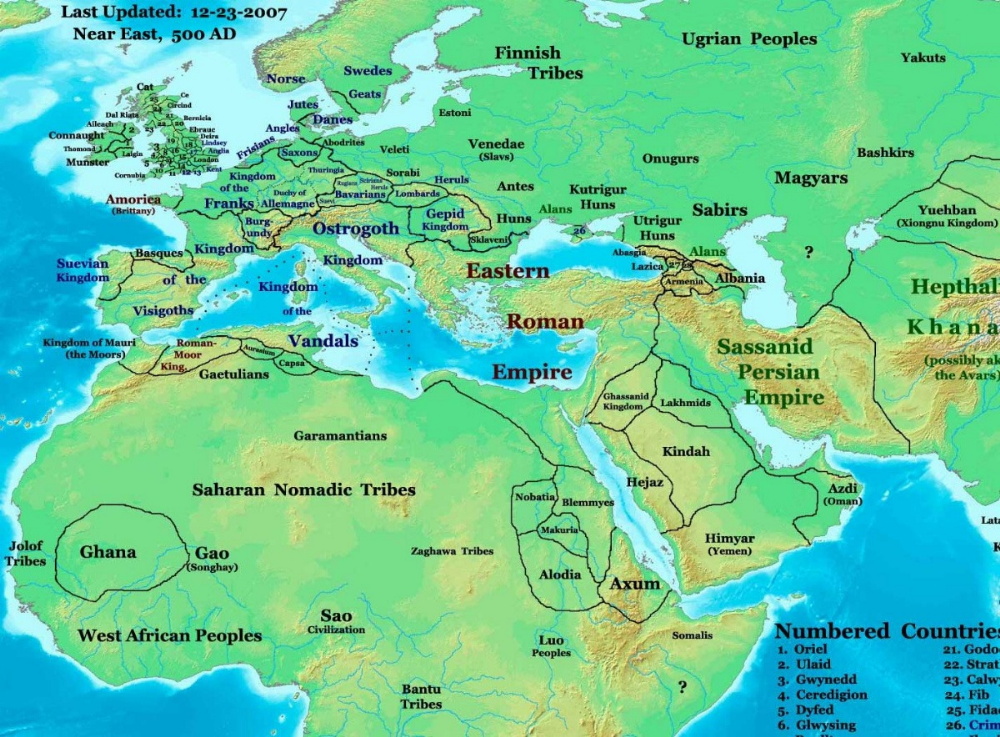

Europe was larger, more complex, and influenced by events on other continents. It extends

to the Arctic Circle, to Iceland after that island was settled by Norwegians in the 9th

century, and eastward into Russia. Turkey considers itself European but, for many years,

was generally considered Asian. Many different peoples/tribes with many different

languages and daily habits and beliefs have inhabited this land mass. Events elsewhere in

China or Mongolia or in Eastern Europe bumped population into different places or wars

caused migration.

Having said this, we return to the Western Roman Empire and its successors. In brief,

outline form, however, for even this small piece of European history is very complex.

Roman Empire under Trajan, 117 CE

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:RomanEmpire_117.svg

The Roman Republic fought “defensive wars” to secure its

borders from any threat; by about 30 BC, it had become an empire ruling the entire

Mediterranean Basin, reaching its greatest limits under Emperor Trajan.

Trajan

It ruled so many diverse people over so much territory that Diocletian, a year after he

won the emperorship in battle in 284, appointed a co-emperor, Maximian Augustus

in 285. Seven years later, in 293, he appointed two junior co-emperors, Galerius and Constantius,

thus dividing the Empire into four parts. Thus, there was no “Roman Empire”

after 285 and there were four after 293 CE. They shared Greek culture as modified by Rome,

Latin as the government language, transportation networks, weights, measures, money, laws

and courts, and a state religion[1] among the

other religions were tolerated. Flavius Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman Emperor,

Romulus Augustus, in 476. The Eastern Roman Empire survived until 1453 although Turks had

gobbled pieces for centuries.

Constantine

Constantine

Unanimity did not exist. Although Emperor Constantine converted to

Christianity in 312 CE and, in 313 CE, the two Emperors, Licinius I and Constantine,

declared that this religion from the Asian desert be officially tolerated, it did not

become the government mandated religion for years. Even when it did, there were different

versions of it. Moreover, there were always other religions, including Islam and Judaism;

different groups migrated into the empire(s), diversity increased.

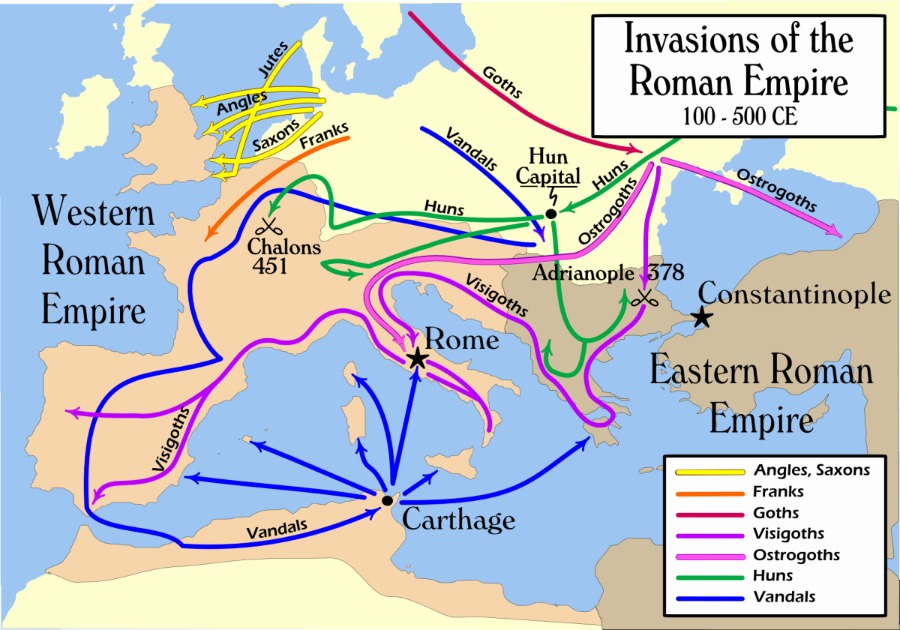

Source: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Invasions_of_the_Roman_Empire_1.png

The central authority of the Roman Empire slowly disintegrated in the 4th and 5th centuries

as people from Inner Asia migrated and fought their way into it. Lynn Nelson in his essay

“Barbarian Invasions and Recovery”[2]

provides a pithy description of what happened. Visgoths, Ostrogoths, Vandals, Angles,

Jutes, Saxons, Franks, Suebi, Alamanni, Burgundians and Huns entered the Empire over the

centuries and stayed, either as groups or through their DNA. The Huns from Asia began

invading and conquering all in their path beginning in the late 4th century.

They penetrated westward into present-day France before being turned back at Chalons in

451.[3] The next year, Attila invaded the

Italian peninsula but left before he took Rome. His losses at Chalons and an inadequate

supply system were telling. He died in 453. Although the Empire survived Attila’s

invasions, it could not cope with so many disparate groups seizing local control. The

unity of Mediterranean world was destroyed when Roman Empire broke up. The Western Roman

Empire was gone by 476. The Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire was centered in

Constantinople and extended into the Balkans, Asia Minor, Black Sea, etc. The third empire

was initially Arabic but eventually became Turkish.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

For 500 years, Western Europe was raided by outsiders, causing disruptions and genetic or

DNA mixing. Trade almost disappeared. The economy reverted to rural, even frontier,

conditions. Such characteristics of the Roman Empire as the use of money, trade, and urban

life broke down. The life of learning continued but with less intensity. This period was

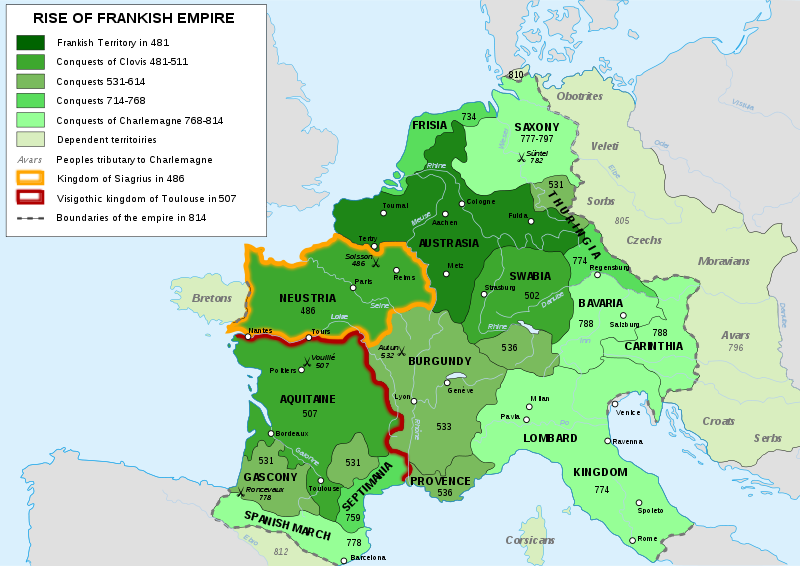

the “Dark Ages” only in contrast to the Renaissance. Significant rallies

occurred during this time such as the Carolingian Renaissance or Charlemagne

Renaissance.[4] Charlemagne strengthened his

position by association with the Pope. The work of Charlemagne was largely undone by fresh

invaders from the north in the 10th century.

Architecture

In the 11th century (1001-1100) the process of the

reorganization of Western Europe began. Secular rulers adopted the feudal system of

governance and the manorial economic system, achieving a degree of stability and security.

The Roman Catholic Church became the leading institution of the West. The Pope became

major a secular figure as well as a religious leader. Feudal institutions and Church

became so pervasive that they extended their influence into 12th century.

The term feudalism[5] came

into use in the late 18th century. It refers to particular organization of

society ending in various points in the countries of Europe. Modern scholarship does not

use the term “feudalism” but, instead sees political power and the economy as

being based on land tenure; almost everyone was engaged in agriculture. Europe was large

so there were variations from place to place. As the central authority dissipated, people

replaced it with more local rule, headed by elites which could command sufficient force to

impose their will.

The inability of the Western Roman Empire to adapt itself to the immigrants who came to

enjoy its benefits caused its dissolution and the rise of a ruling warrior class in

numerous and various parts of the old empire and its neighboring areas. These warriors and

their allies, the clergy, maintained their supremacy by force and tradition, living from

the labor of the peasants the vast majority of the population. The outstanding feature was

the contract between the ruling lord and his vassal. The lord was always a warrior in

ruling class. The vassal agreed to provide service to his lord. In return, the lord gave

him a fief, an estate-unit of agricultural income, tools, peasant serfs, etc. The fief was

a unit of agricultural income but also a state-within-a state which administered

justice, tax, tolls, military forces, etc. It became inseparable from political authority;

it became the new basis for political organization. The system regulated the

relations among the ruling class by imposing a hierarchical structure.

All fiefs were originally granted by king. William the Conqueror divided all England into

fiefs and gave them to his vassals in the process dispossessing the former English

holders. A vassal receiving from king could donate to lesser person if he wished in return

for his service. This process was called subinfeudation. Archbishops and bishops held land

from the king. They gave land to knights who performed military services which were

required of priests.

In practice, fiefs became hereditary. Male heir had to perform homage and take oath of

fidelity to his lord. A female couldn't inherit a fief because she wasn't a warrior, but

her husband could. Since the fief was granted in return for military service, the vassal

had to appear in person for judicial and social functions. The vassal had to provide

financial aid such as payment upon the eldest son’s knighting, marriage of the eldest

daughter, and ransom if the lord was captured.

As European economy changed, as money reappeared, as middle class began to grow into

towns, kings began to consolidate power. Nobility suffered at the extension of king's

power, but gradual change helped.

The manorial system was labor attached to land. Land needed labor to work it. Under the

terms of this system, the peasant-serfs worked the land, providing food for the manor;

the rulers provided defense. The system included not only peasants-serfs but also

artisans. The peasant-serf had obligations and rights. He was not a slave, per se, but his

freedom was circumscribed. He couldn't leave of own free will but he could be sold to

another lord. Serf could pass his land tenure to his son. The average land holding was 30

acres. Fields plowed and worked in common. The layout of a community was houses built in

the center of land, fields around. The farm hand had to work in his lord's fields to support

the lord and the lord’s people. The serf was required to provide labor for bridges and

roads (corvée). He was free from military service except during sieges. He made payments

in produce. The serf was taxed if his daughter married outside of manor because the lord

would be deprived of her and her offspring’s labor. The serf paid an inheritance tax.

A tallage (land use) tax could be levied annually or whenever money was needed. The serf

was obliged to pay bonaliter to use a mill, ovens, or wine press. The Roman Catholic

Church demanded a tithe (10%) and sometimes demanded more for construction projects.

The lord’s or vassal’s income was from the manor and this placed a heavy burden

on the broad peasants' back. Income from manor was income of lord whether cleric or

layman. The peasant supported whole temporal system as well as spiritual system. The lord

of the manor was responsible for keeping law and order. He protected serfs in times of

danger. His steward generally kept law and order. The peasant village was, generally, at

the foot of the castle. Security of the castle was paramount. Frequent holidays were

beneficial to the peasantry. The peasant population increased and more forests were

cleared for planting. The manorial state differed from the modern state because almost all

people were not legally free, having special obligations, and were subject to

idiosyncratic legal systems. Nevertheless, the system was the best that could be provided;

it prevented anarchy for it provided laws and rules.

The system left valuable legacies such as trial by peers(ruling class-primarily),

concept of limited sovereignty of king, mutual rights, guaranteed certain rights, ideals

of the code of chivalry (standards of gentlemanly conduct honor, loyalty).

Papacy and the Roman Catholic Church

At the same time the power of secular rulers ebbed, so, too, did the influence of the

Roman Catholic Church. Some argued that it was in need of reform, that it should not allow

clerical marriages, simony(the sale of clerical favors), the sale of indulgences,

forgiveness, and/or protection) sale of clerical offices. In other words, they argued that

it had been corrupted since its founding, deviating vastly from what had been taught by

its founders. In one way of looking at it, Western Christianity had become ungodly. It was

much like secular society.

To those who believed that the Church should be supreme, lay investiture-investing of the

clergy with the symbols of his spiritual authority by laymen (kings) was a problem. The

Papacy (which wanted to be supreme) objected because this meant that the king was

all-embracing. Who had the allegiance of the clerics, the Pope or a king? Many of the

Church hierarchy had a dual capacity; they were part of the ruling class possessing land,

vassals, and, even, military duties and did not focus on the spiritual life.

By last half of 11th century (1051-1100), there was a spiritual revival and the

rise of the papacy to significant powers and position. The Clumiae movement from monastery

of same name attacked the three evils above. In mid-11th century reform carried

to the English church by William the Conqueror.[6]

The Germanic king and Holy Roman Emperor Henry III worked to cleanse the papacy.[7] Strong Popes, especially Gregory the 7th,

changed the institution by regularizing the choosing of the Pope through the College of

Cardinals[8]. The election of the Pope was

taken from the hands of nobility to Rome. Gregory VII also attacked the centuries-old

practice of the clergy getting married; he and his advisors demanded the sole loyalty of

the clergy.[9]

The Holy Roman Empire claimed to be the successor of the Western Roman Empire which had

ended in 476; Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Emperor in 800 CE but it was not until Otto

I, the elected German king, was crowned Emperor in 962 that it really existed. Emperors

were elected, as was the German custom, and anyone with any pretence to power tried to

control said elections.

The strengthening of Pope and Church created a conflict between the emperors of the Holy

Roman Empire.[10] These Germanic rulers were

accustomed to having a large say in who became Pope. The issue came to a head over

question of investiture. Who was supreme over choosing the clerical head-temporal or

spiritual powers? Gregory VII asserted that only the Pope had the power.[11] Gregory won this battle with Henry IV in 1077 by

excommunicating him, an act which required all true believers to shun him. Henry trekked

to Canossa at the residence of Gregory VII in the northern part of the Italian Peninsula,

stood bareheaded in the snow for three days, and begged forgiveness. The two continued to

battle. In 1084, Gregory lost to Henry and retired into the exile in San Angelo. Henry

created Clement III who then crowned Henry as Emperor in 1084. Gregory was not pleased. It

took another half century before the issue was settled by compromise, the Concordat of

Worms[12] in 1122 between Calixtus II

(1119-1124) and Emperor Henry V (1106-1125). To wit, elections of bishops and abbots in

the Germanic kingdoms would be held in the presence of emperor or his representative.

Secular power was given by emperor, spiritual power to the Pope (Church).

The struggle continued by their successors. One famous struggle was between Henry II of

England and Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, who was struck down at an altar of

Canterbury Cathedral by four knights in 1170. They had been good friends until Beckett

assumed independence of the king. There were very real struggles between strong monarchs,

whether English, French, or German, and the hierarchy of Church.

Under Innocent III in the 13th century, the Church reached the acme of

intellectual, spiritual, and temporal power. The Pope became temporal head of Italy. The

Pope was also feudal lord over numbers of kingdoms. King John of England became vassal of

the Pope as did many other kings. Innocent III was a brilliant administrator, and spread

himself from spiritual to temporal power. He improved money collection, laws, and courts.

He asserted that canon laws covered not only ecclesiastical matters but secular aspects

also. The Church was threatening the temporal power of Frederick of Sicily, John of

England, and others; Innocent III overcame these monarchs.

Two heresies threatened the spiritual power of the Roman Catholic Church.

Waldensian—spread into Southern France and Low Countries. Catharism[13][1]-most

sinister, support from important ruling class, slaughtered those who took up these

heresies. Innocent III launched the 20-year Albigensian or Cathar Crusade (1209–1229)

to eliminate heresy in Languedoc. Spiritual orders—Dominicans, Franciscans,

Cistercians—did great deal to reform the life of the Church and to fight

heresies. The Church’s efforts to stamp out heresies in the 13th century

were much simpler than in the 16th because political and social conflicts never

joined with spiritual/theological issues. Western Europe remained united in the common

Roman Catholic Church. In some ways, it was a kind of Christian republic (Republica

Christiana) except, of course, for those areas of Europe controlled by Muslims and except

for the small number of Jews and other non-believers.

The Church continued to exercise intellectual and artistic power throughout the period.

Universities were started as a school to train clerics. Almost all people were illiterate

in Latin and in whatever local language but priests had the necessary ability to read. Any

person accused of a crime who could read Latin was allowed to plead benefit of clergy.

Clergy and those with benefit of clergy were tried in church courts which had no death

penalty. Secular courts were harder, more strenuous.

Medieval Christianity believed that the highest, the purest activity of a human was to

devote one’s life to the worship of and service to God. Thus, theology was preeminent

in the high Middle Ages. The highest class or first estate was the clergy. Functionally,

those who were governed by the rules of a holy order, regular clergy (monks) had higher

caste than secular clergy. Regular clergy were seen as being more god-devoted than those

who served the common man, the hoi polloi, because contact polluted them. The clergy was

also subdivided between bishops and abbots, on the one hand, and ordinary priests, on the

other.

Theology was supreme in the university; philosophy was its handmaiden. St. Thomas Aquinas

summed up his arguments in Summa Theologica. He knew some P1ato and Aristotle and

combined this with orthodox Christian theology. Started with the assumption of God-given

truths and then used the deductive method of reasoning. The danger is in departing too

widely from fact and experience. He kept within those bounds. He was one of the great

philosophical systematizers of Western thought. He asserted that the human will cannot

wholly transform but can adjust.

Respectable work was done in science by clerics. The most outstanding was Roger Bacon, a

Franciscan friar, who did not question Church, but relied heavily on the secular

Aristotle. He tested some of Aristotle’s assumptions and criticized their veracity.

He believed in experience not reason to determine what is real. Rather than rely upon

deductions derived from “revealed truth” he relied on inductive reasoning. He

did work in optics of significant interest.

The Church persuaded its believers to build churches, including monumental cathedrals, to

the “greater glory of God” as they put it. To deny the church funds was to deny

God, so the argument went. Churches were the public buildings of the medieval

period and usually the only buildings that survived. Church architecture illustrates many

areas we see seen in other parts of the culture. They used inductive reasoning on

building. If it worked, it was copied; they were pragmatic. The 11th to 13th

centuries were important in art, monumental sculpturing, breaching great spaces, and

ecclesiastical building.

Romanesque was the style from 1000 CE until 1150 CE; the Gothic style began about 1150 CE

and lasted for the next three of four centuries. Gothic was more northern than Italian.

Romanesque was related to Eastern Byzantine and northern barbaric styles. Northern

barbaric styles were full of eccentricities, asymmetrical, and dissolving silhouettes.

There was more variety than unity and many regional variants from the Roman style. No

styles were identical. It used church towers, rounded arches, and compounding of vaults.

Arches and buildings were not precise and sometimes faulty. The Leaning Tower of Pisa

leaned from the beginning. They didn't care if it leaned. Much was left to improvisation.

Many churches fell down; they had to start all over again. Romanesque churches are

picturesque and lovable. Their parts are delicate rather ponderous. The use of colors was

common. The plan of it is that of a Christian Basilica, a functional plan.[14] Romanesque churches are profusely adorned with sculpture,

generally religious, done on a commission basis. In the north, they borrowed from books

and used mythological animals, called bestiaries. Many of the pieces of sculpture were

hideous. They were not concerned with beauty, but with the telling to the Christians the

story of what would happen to them if they did not behave as the Church wanted.

The Gothic style originated in 12th century France on the Île de

France. Northern France remained the center for this style for 150 years. It was a region

of rich soil with strong efficient government, thus bringing peace for awhile. Farmers

became wealthy along trade routes. Surplus wealth facilitated building large, expensive

buildings. Paris had the university where St. Thomas Aquinas worked and studied. French

Gothic is the expression of the philosophical concept of harmonious balance of each part.

Every part had to be examined as to its rationale. Building a cathedral required knowledge

of the Christian understanding of the world. Gothic is a misnomer. Gothic reflects the

freedom from Rome. It reflects the Northern barbaric style, the effect of pointed arch and

ribbed vaulting. Amiens Cathedral had much glass and stone. Stone roof which is partly

supported by flying buttresses which don't block windows. The Cathedral, dedicated to the

Virgin Mary, was completed in 60 years. Gothic is very ornate, complex. We know the names

of the master builders, but nothing about how they recruited labor or anything else.

Amiens Cathedral

The plan of these churches is Romanesque, more or less. Amiens was

built inside a town. The important facade was built on the west side of square. To

construct such a church was daring for it used less mortar per cubic area and a pointed

arch to control the thrust. The Gothic style spread in the 13th century as did the Church.

Economic and Social Changes in the Middle Ages

Industry and commerce revived and towns arose[15]

with commerce occurring first. There was much interaction among all three. Most of the

towns were new. European civilization expanded. Commercial activity revived first in the

Mediterranean because it had never ceased there. Constantinople, city of a million people,

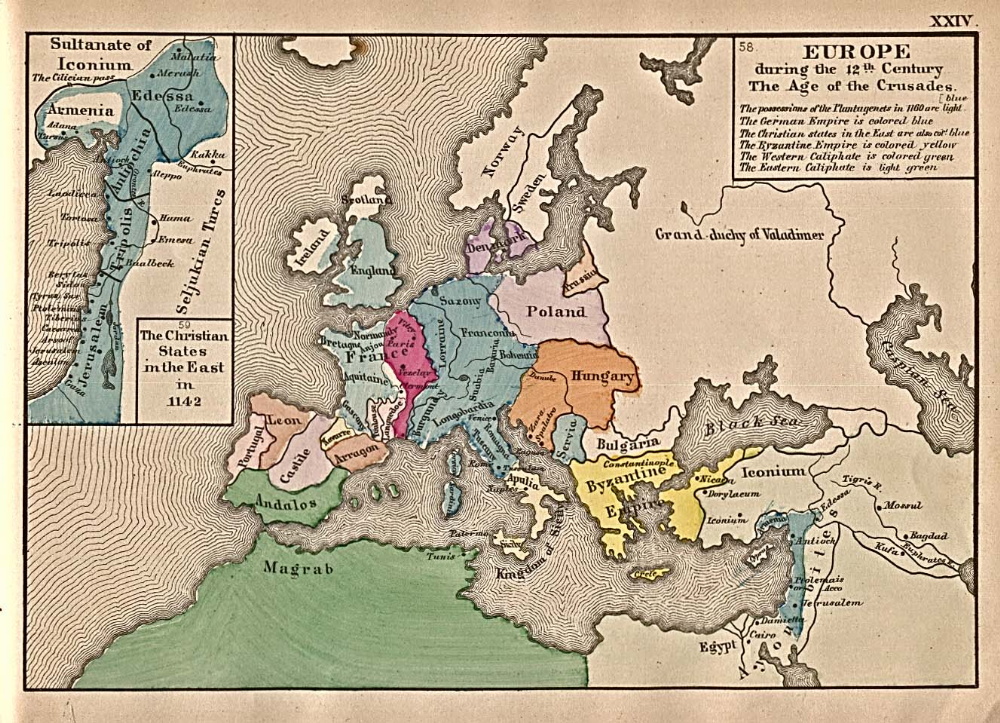

had to trade to survive. The Crusades (1096-1272)[16],

Roman Catholic military invasions of the Holy Land to wrest control from Muslims, helped

commerce for it brought western and central Europeans into contact with eastern Europeans

and Asia Minor. Merchants from Genoa, Pisa, Venice, supplied English, French, and other

Crusaders in order to get rights to trade. These merchants prospered in supplying

Crusaders and trading with Orient. Commerce spread west to Marseilles and inland. The

region of the Lombardy plain took lead, followed by the cities of Pisa and Venice. Soon,

trade breached the Alps into Northern France and Germanies, spread to Holland, and across

the English Channel to London. Then another trade developed in the North to supply other

commodities than the Piedmont and Mediterranean products. The demand for Flemish woolens

caused them to import raw materials (wool) from England. English wool was of finer

texture. Flanders became a region of weavers and fullers in 12th century, a

source of wealth for many towns.

Commerce into the Baltic Sea region was promoted by Hanseatic League

(German merchants) formed in the early 13th century. It served as an

intermediary between Eastern and Western Europe. The League’s east was a frontier;

its merchants had to establish their own posts. Fur trading was important.

Towns were born or grew. Industry stimulated migration to towns. Many

were runaway serfs. If a runaway serf resided in a town for a year and a day, he was free.

Towns developed their own economy. Merchants developed their own law, "jus

mercatorum." They established separate tribunals, organized a town group to levy tax

for defense and improvement. They assessed the tax according to individual’s wealth,

that is, a progressive tax. It was collected by the town council and magistracy. Townsmen

sought charters from lords of the region. Some lords saw the rise of towns as another

source of revenue and gave charters upon receiving a payment. The towns could play one

lord against another to secure a charter or to improve its conditions. Some members of the

town formed a new class called the third estate. Civic pride pervaded medieval towns.

Town life was inimical to peasant life. Town-rural conflict has been

going on ever since the rise of towns. Prices of fuel and food were minutely regulated.

Wages and production were controlled by the craft guilds, corporations enjoying the

monopoly of practicing their craft in accordance with regulations set by public authority.

Purpose was to protect members by assuring monopoly of their particular craft. Towns

controlled price and quality.

People sought stable conditions in a stable industry. The medieval attitude tended to

limit initiative and individual progress. Stability, not change, was the ideal. Merchants

came from a period of anarchy and were trying to establish themselves. The typical craft

guild structure was masters, journeymen, and apprentices. The Master owned the small shop,

tools, and products. They were small capitalists. A journeyman was on his way to becoming

a master; he had no shop or tools. The apprentice was learning the trade; he was protected

against malpractices. In towns which produced material for export like the cloth towns of

Flanders, the workers organized in guilds were only wage earners. Merchants obtained raw

materials, put out for spinning to one group, fulling[17] to another group, weaving to another group, dyeing to another, etc. He

owned it, paid to have it worked into finished product, then traded it through the routes.

Those engaged in making export products had not as much protection as other guilds. They

engaged in strikes and other forms of protest. Trade experienced boom periods and

depression. The periods of anarchy in this organization explain why some guilds clung to

their organizations.

Towns affected agriculture and the peasant-serfs. Provisioning these cities led to

increased agrarian activity; land was utilized that hadn't been before. Villes neuves[18] in uncultivated lands used to build

agrarian towns. Landowners lured men by the promise of rent payments and exempting people

from the old manorial dues. The free peasant who appeared in many of these agrarian towns

received charters and enjoyed same legal autonomy as the industrial towns. Some towns

emerged in frontier locations. The status of the new towns affected the serfs of

neighboring manors. They agreed to pay quitrents (cash payment for their work) which

released them from the old manorial payments/regulations.

By 1200, serfdom had virtually disappeared in Flanders and was disappearing in France.

Serfdom survived only in places remote from trade. It died out in areas where industry and

commerce flourished. In conservative and backward Russia serfdom began in the 18th

century, however.

Age of Renaissance in Western Europe

Leaders of the Renaissance thought of themselves as modern, as making a complete break with

the past but this was inaccurate. There was a shift in attitude, intellectual activity,

and the arts but it was spread over several centuries. Learning revived in the 12th

century. Trade and the money economy began in 11th and 12th

centuries. Contrariwise, some medieval systems continued far past the Middle Ages. England

didn't revamp its economy and its courts until the 19th century. The Christian

view of the Middle Ages was not challenged until the 18th century. Earlier

historians limited the movement to the intellectual emphasis which began to take place but

that view is too limited.

Economic and Social Changes

There was no sharp break. Little change occurred in the manner and spread of land or sea

transport. Distant communications depended largely on horseback and caravans. Wheeled

vehicles were used for short distances because of the lack of good roads. For sea

transport, sails were modified but oars were still in use. Ninety percent of the

population lived from the soil. Only half dozen cities exceeded 100,000 populations. The

bourgeoisie (town-dwellers) were a small minority but they were a dynamic element in

European society; their influence was far out of proportion to size. This “middle

class” still lacked wide recognition, for much of the medieval law recognized only

three classes-lords, clergy, peasants.

Class structure and social mobility changed by the 15th century. Nobles had

more political power than the middle class but were losing military power. The clergy was

hardly social and economic class; it enjoyed a separate legal status with certain

privileges and immunities, such as only being bound by canon law. Members of higher clergy

owned land and were feudal vassals with obligations to a lord. The positions of abbots and

bishops were often filled by members of the nobility. The parish priest frequently came

from peasant class, often a bright peasant son. These priests were no better off than the

peasants they served. They, of course, were the front line of the Church.

Middle-class towns had even less homogeneity. Both the upper and lower middle class were

lumped together as bourgeoisie. The special quality of the bourgeois was being a man on

the make, expanding, q professional. All such occupations were subversive to the

established order. The discovery of the New World brought inflation as gold and silver

poured in from Peru and Mexico, inflating the currency, and creating hardships on those

with fixed incomes. Lawyers investigated feudal charters so that the king could take away

special privileges of nobles. Townsmen were a revolutionary element in Europe. The economy

expanded so rapidly, it was almost a revolution. New industries such as printing, cannon

founding and silk were created, in part, because of explorations. The New World became a

vast hinterland, an extension of Europe. The expansion of the European economy was chance

rapid but little understood. The pace was very different from what Europe had experienced

in centuries and it squeezed static structures. For example, some landowners converted to

sheep runs, forcing peasants off the land, so they could sell raw wool to the cloth trade.

Lesser nobility often racked by money lenders and usurers. It was difficult for the

average person to understand the changes. Few understood or believed in progress; they

were conservatives, seeing change as a worsening of life. Characteristic was Sir Thomas

More, Utopia, wherein he condemned change, blaming it on Christian failing. The

money economy caused the development of banks and sophisticated devices to handle the

expansion of business.

Political Changes in 1500 and thereabouts

Similar to the tempo of change of economic and social conditions, the

political change was not sharp or abrupt. Europe wasn’t unified, in spite of the

claims and hope of the Holy Roman Emperors. There existed many independent states with

distinct boundaries and kings at the head who were competing for power. They

weren’t as absolute in power as would later be, for these governing units were still

linked with the medieval past, which set limits. Monarchs were stronger than before and

the feudal nobility was greatly diminished and would become even more so as rulers found

more ways to emasculate them. The peasants were burdened no matter who ruled—monarch,

feudal lord, or clergy. Whenever it appeared that a ruler who could rule, the “middle

class” (bourgeoisie) backed him for despotism was better for business than feudal

anarchy.

Who should rule is a constant question, of course, and whoever rules seeks justification

in some kind of theory. In the latter half of the 16th century, Jean Bodin [19](1576), in De Republica, provided

a secular justification for monarchical rule. He asserted that power is expressed in an

association of individuals and their possessions ruled by a sovereign power, who,

according to reason and the essential manifestation of sovereignty is to make and enforce

laws. He cannot be bound by what he makes, because king made the laws. He is bound by the

law of reason of nature, the divine law common to all nations; he is bound by constitution

of the State. Bodin reflected Roman and medieval tradition. The trend was towards strong

centralized power/government, providing authority and order first and liberty second. This

tendency was exemplified by Italian states.

Background of Italy

Hohenstaufen rulers sought to extend their control over northern Italy but failed (11th

and 12th centuries). By the 13th century (1201-1300) Italy was free

from Germanic domination. Northern cities were independent. The Papal States were no

longer threatened by foreign encroachment. The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies had passed from

the German line to the French Angevin line. After 1300, city-state history is important

for Italy was only geographical expression and not a country until 1861. In the northern

part of the peninsula, Venice, Florence, and Milan were the major cities. By 1500, these

three had become the cultural centers of Europe as their mercantile wealth accumulated by

“international” trade provided the funds to subsidize cultural activities.

Merchants had taken full advantage of their geographical position and had traded in

luxuries, for such brought the highest value for their weight. Later other imports, such

as fruit, cotton, silk, and perfume were added. Milan on the Lombardy plain became the

center for trade between Italy and North, as well as for goldsmiths. Florentine artists

refinished and dyed cloth from Flanders and were masters of the tooled leather industries.

Venice became a ship building center and was the most important port of Italy. It was

famous for its glassworks, particularly Murano glass. Northern Italian cities experienced

a major industrial revolution. Money lending became banks, replacing the money

services which had been provided by Jews because Christians were forbidden to charge

interest on loans. The Church objected to loaning money at interest (usury) because it

asserted that doing so taking advantage of people in need. That the Church loaned money at

interest was seen as different because the profits were spent by the Church to maintain

itself and do good works. Florence took the lead. The Florentine gold piece, the florin,

was the symbol of the wealth of Florence and highly sought in Europe and in the

Mediterranean. Italian bankers worked out the fundamental techniques of capitalism such as

partnerships, double entry bookkeeping, and investment capital. Religious scruples against

the taking of money gave way to needs of commerce and of the Church to finance trade,

industry, wars, and such.

Trade led to commercial and political rivalry. Each city reached out to bring rural areas

into its power. Rich burghers invested some surplus in rural land, often country estates

for prestige. By 1300, nearly all the rural land was owned by these burghers or lords who

delved in trade and industry. One result was the disappearance of manorialism;

serfdom was replaced by wage system or sharecropping. Agriculture changed to cash-profit

basis, supplying city market from surplus.

In these urban republics or city-states, actual authority resided in rich merchants known

as grandi. The old patriciate of nobles and burghers possessed prestige of having led

city-state away from the domination of Pope or emperor. The nouveau riche was eager to

harness state policy to further own interests. In Florence they were known as Fat people,

popolo grosso, in Florence. Below these were the plain people, populo-artisans, guild men,

and the middle class of burghers. They opposed the economic imperialism of populo grosso,

but sided with them rather than the grandi or the popolo minuto. Most numerous people were

the popolo minuto.

Between 1300 and to 1500, the classes struggled among themselves for relative position and

wealth. Venice was the exception for the merchant families ruled under a republican form

of government. The Doge was elected from one of the ruling families. The populo grosso

were strong enough to exclude the grandi from office by admitting some of the populo to

minor office. In 1378, successful rising of the popolo minuto, the Revolt of the Ciompi,[20] was short-lived proletarian rule. By 1382,

the populo grosso was back at head of states until 1434. Cosimo di Medici[21] relieved them of their power de facto not de jure. Medici

family was the uncrowned head of the Florentine state.

In the interest of security and peace, upper class chose One person in which to put all of

the power, podesta[22]. The chaotic

condition of Italian city politics encouraged a strong man to take control of the city.

Milan’s bitter warfare between nobility and the people led to the rise of two groups,

the Della Torre[23] and the Visconti[24]. The latter won and ruled to the middle of

the 15th century. They were harsh, cruel, and prone to assassinate one another.

They patronized the arts to gain prestige. After last male died, Francesco I Sforza[25] took over, married a female

Visconti, and patronized the arts tremendously.

The government of the city-states on the Italian peninsula were often more rational than

the Northern states. They were social laboratories with the first graduated income tax,

public works programs, and first census. They were less bound by traditional, moral laws.

Public morality was different from private morality. Niccolò Machiavelli[26], The Prince, defended what was rather than

what should be. Acts of clemency, morality, and justice were second to the interests of

the state. So much for traditional Christian morality.

South of the northern city-states lay the Papal States, for the Bishop of Rome was also a

secular ruler. This temporal area of the Popes could not be isolated from the North from

1305 to 1378 when the Popes resided in Avignon (sometimes called the Babylon

Captivity)[27]. The Great Schism[28] followed, lasting through 1417. Two popes

and then a third, the first John XXIII, were elected and consecrated as Pope while

Christians in Western Europe fought to insure that one of their own would lead the

“universal church.” The Papal States were attacked by neighbors and Roman

nobles. Rome became a provincial city. Popes returned and the city started recovering. The

Papacy weakened by schism and Conciliar Movement,[29]

which asserted that the Council was final authority. Not until the mid 1400s did the

Papacy recover. Strong popes used temporal methods such as war to fight their neighbors.

Further south on the peninsula, The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies had been divided in late

13th century when the island of Sicily was captured by the King of Aragón. The

capture of the fa11 of the Eastern Roman Empire by Ottoman Turks in 1453, led to the

decline of brilliant civilization under Roger II, Norman king[30]. With the great revival under his grandson Frederick II,

the Kingdom was converted it into a modern state with centralization and a

brilliant intellectual life. Trouble plagued the Kingdom as outsiders intervened, rugged

mountains fostered isolation is area; peasants were landless; landowners hired pug uglies

(Mafia, Black Hand) to maintain power, and factionalism was rife. Commerce failed to keep

pace with northern city-states. By 1500, it became a backward area. The House of Aragón

became the ruling house over Spain and Aragonese rulers were able to exert influence. The

Kingdom of Two Sicilies was going to play an important part in the politics of Italy.

Mercenary armies and strife kept the states apart. A disunited Italy escaped invasion

because neighbors were otherwise engaged. The French fought England and Burgundy in the

100 Year's War. The Iberian Peninsula fought the Moors. Each was trying to force influence

on other Christian states. The German states suffered from terrible internal strife.

In this period, the first balance of Power system developed, a group of independent states

trying to keep each other from becoming too powerful in Italy, Florence and Milan alliance

with Kingdom of Two Sicilies against Venice and Papal states. The alliance system weak

against foreign invaders; England, Spain, France, once united, were able to look elsewhere

for expansion. The Italian Peninsula offered the chance to divide and conquer; it began in

1494, Charles VIII of France led expedition into Italy as far as Naples. The

invasion collapsed in 1496 as the result of disease and bad organization; foretaste

of what was to come. Italy in the 16th century became a battlefield between

France and Spain. The Italian states used as pawns during these wars.

France, by 1500, had become one of the leading European powers; it was the largest

territory in Western Europe under one ruler. By 1453, it had won the 100 Year's War[31]. English kings since William the Conqueror

had possessed French feudal lands. The 100 Year's war began when Edward III pursued his

legitimate claim to the French throne over the claims of Philip of Valois, the choice of

the French nobility who would not tolerate an English ruler. It ended as a war between two

nations. It created nationalism; national feeling was aided by the “moat: that was

the English Channel. The French crown was aided by the rise of the middle class in towns

who sided with the king because he meant security. France had geographical and climatic

advantages and a rich soil. France prospered in spite of the war. Charles VII (1422-61)

had a weak character but was surrounded by able people (“the Well-Served”). Joan

of Arc, whose military feats insured the coronation of Charles, is also a symbol of French

nationalism. During his reign, the English driven from French soil and the first permanent

army was created and a military supply system was created. Militaries consume vast amounts

of funds. The Estates General voted the first land tax, the taille. Once levied, it became

permanent. Finances were put into order by Jacques Coeur[32]. The monarch was strengthened in the secular realm but also in Church

affairs. The Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges[33]

(1438) granted the French or Gallican Church a large amount of autonomy. The

French king exercised substantial degree of control over church in France and enjoyed a

high degree of freedom from Papacy.

Louis XI improved the things that Charles had started, pursuing broad economic policies.

He was a good administrator. He extended the royal domain with his victory over Duke of

Burgundy, Charles the Bold[34]. He took part

of the Low Countries. The remainder passed to the House of Hapsburg when Duke's daughter

Mary of Burgundy married Maximilian and he agreed to defend it. Maximilian was heir to the

Holy Roman Empire. The Angevin Louis XI assured the direct annexation of Brittany by

marrying his son to the heiress of Brittany. The grateful people of France allowed Louis

to proceed without much interference. At one meeting, the members of the Estates General

said that the king could rule without them, that he could levy taxes including the taille,

aide (an excise tax), and the gabelle [35](salt).

These taxes produced the necessary money for diplomacy and war but stepped on liberties.

There was a steady encroachment upon municipal liberties, feudal rights, etc.[36] on the other hand; he sought support from

the Pope by repealing the Pragmatic Sanction 1461.

The Estates General declined under Louis XI. There were three Estates in France, the

clergy, nobility, and commoners. Nobles had to attend it as service to king. There were

different ways of choosing who went to the Estates General. The Estates General was an

advisory (not a legislative) body which the king expected to support him. He wanted

approval of his line of conduct; he wanted as many people as possible to support his

policy. When Louis XI died in 1483, the royal authority was paramount and buttressed by

permanent army, permanent taxes, institutional support, and encroachment of liberties.

Estates General had been called only once. France was on its way to becoming

a strong centralized state.

England was a power to be reckoned with even though it had been weakened by losing to

France and then the War of the Roses[37],

when the House of Lancaster fought the House of York. It was an anarchic period. The

English middle class welcomed the peace and security the Welshman Henry Tudor (Henry VII)

brought when he defeated Richard III on Bosworth Field in 1495. His claim to the throne

came via his mother of the house of Lancaster but he wisely married Elizabeth, daughter of

the House of York. He created the Star Chamber[38]

as the only way he could prevent certain nobles from continuing anarchy was to bring them

to court. He created the foundation of powerful monarchy not based upon standing army

because of English Channel. Tudor power rested on popular approval. Parliament had

developed into intricate part of the Constitution and developed a life of its own. It had

taken its present bicameral form and become a truly legislative body with power of

taxation. The boundary of power between Parliament and the monarchy was always disputed,

of course. A king who wanted to levy a tax had to go to Parliament (Commons) for approval.

Popular monarchs with popular program could handle Parliament. By time of Elizabeth I's

death England counted as major power, one that could and did resist Spain.

Spain[39] was a geographical expression

containing several kingdoms but which was finally virtually united by the wife and husband

team of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragón. The Moors were conquered and driven

off the Iberian Peninsula at Granada[40] in

January 1492. The Peninsula contained the kingdoms of Portugal, Castile, Aragón[41], and Navarre. It would not be until the

accession of their daughter, Juana la Loca that both kingdoms had the same monarch but

Juana’s parents took measures to create some unity while each administering the

affairs of their respective kingdom. Close relations with the Church allowed them to use

the Inquisition to seek uniformity. They followed a common economic policy as much as

possible. Augmentation of monarchical power was facilitated by commerce and revenues from

the New World. See Donald. J. Mabry, Spain,

1492-1598.[42]

Portugal,[43] the tiny kingdom on the western

shore of the Iberian Peninsula, was established as a kingdom in 1139 by its leader Afonso

Henríques; recognition came from King Alfonso VII, king of León and Castile in 1143 and

Pope Alexander III in 1179. By and. By 1249, its borders were set with the Moors having

been driven out of the Algarve in the south. It is the oldest nation-state[44] in Europe. It was also the first nation to

make contact with the Far East, directly. Its explorers gave it claim to Ceuta, the

Azores, Brazil, Macau, Goa, Ormuz, and Malacca. Portuguese independence disappeared from

1580 to 1640 because the Spanish king, Philip II, the son of a Portuguese princess,

invaded and took control, and had himself crowned Philip I of Portugal.

Three distinct religious groups—Jews, Christians, and Muslims—lived on the

Iberian Peninsula in relative peace until the Crusades. Muslims invaded in 711 and

conquered most of the peninsula but tolerated Jew and Christians as fellow people of the

Book, the Old Testament. Learning and culture flourished. The Christian crusades against

the Moors excited Spaniards against Jews and Moslems and they became intolerant. Religious

conflict agitated by merchant conflict. The policy of persecuting non-Christians became

popular. To be Spanish was to be Christian according to Spanish nationalists. Portugal was

not so intolerant.

Germany, a geographical expression, was a bewildering patchwork of independent

states/countries varying in size, complexity, and importance. It was the center of the

Holy Roman Empire which was none of these three things but a collection of duchies,

counties, two kingdoms (Denmark and Hungary), many autonomous groups, a large number of

bishoprics (which were secular powers as well as religious institutions), a large number

of free towns (granted independence by royal charter, and knights with autonomous powers

living in their Rhineland castles. The northern Italian states excluding Venice were part

of it for a time. The head was traditionally a Hapsburg. The Emperor was elected, but the

policy was to keep the crown in Hapsburg family who had established dominance and who were

beginning to think it belonged to them.

Source:www.vlib.us/medieval/lectures/hundred_years_war.html

Source:www.vlib.us/medieval/lectures/hundred_years_war.html

The Emperor/king had prestige but little power, which came from

hereditary Austrian power and the Low Countries by marriage. Within the Empire, war was

endemic because emperor failed to raise the money necessary to keep order. Free cities

formed alliances to protect their commerce. The Swabian League, established in 1488, was a

confederation of bishops, principalities, knights, and cities which asserted that the

Emperor had to consult them, that he could not impose his rule. Such was not the view of

the Emperor Maximilian.[45]

As a result of this weak central authority, there was more tension there than the rest of

Europe. Peasants were rebellious. Some of the Germanic upper class began developing

nationalist attitudes. They directed their hostility against the Roman Catholic Church,

which was Italian. They expressed a willingness to follow anyone who would defend the

Germanies (prostrate) against Italian harpies. They believed that the Church hierarchy was

draining money from Germany through indulgences, and the temporal undertakings of the Pope

and the bishops.

The Renaissance

John Hus

John Hus  John Wycliff

John Wycliff  John Calvin

John Calvin Martin Luther Source: www.covenanter.org/Luther/martinluther.htm

Martin Luther Source: www.covenanter.org/Luther/martinluther.htm

Luther was trying to remodel Christianity after earlier

Christianity, the religion before it had been corrupted by humans, before it became

selfish and egotistical and self-serving. In short, before Christianity became

anti-Christian.[63]

His ideas were spread partly by books, converts, and Wittenberg events,

which remained the nerve center of Lutheranism. He had an educational institution in which

to develop his ideas. Enrollment increased. His main interests were the Germans and

Scandinavians, but his Latin writings went everywhere. Other places that were strongholds

were Zurich (Ulrich Zwingli) and Strasbourg. Zwingli argued that the Eucharist was

not the eating of human and divine flesh and drinking of human and divine blood but

nothing more than a memorial of the Last Supper. Luther had argued that the

Eucharist/Communion was the presence of Jesus Christ in the bread and wine but neither was

transformed into flesh and blood, the position known as consubstantiation.[64] Martin Bucer (1538-41)[65] made Strasbourg the most tolerant city in Europe,

influenced Calvin to take refuge there. He asserted that Jesus was present only to true

believers in Eucharist.

The rapid spread of Lutheranism in three decades was appalling to

Catholics. First to feel the impact were the free German cities; by 1530, a number of

German princes had swung to Luther as well as the kings of Denmark and Norway, and Sweden.

In 1530, the Augsburg Confession (the Lutheran Creed) was adopted. Phillip Melanchthon[66], the other great founder of Lutheranism and

the principal author of the Augsburg Confession, was more moderate than Luther. When

Luther died, the Germanies were split religiously. There was a religious war between

Charles V, the Hapsburg ruler, encouraged by the Pope, and the Lutheran Schmalkalden

League.[67] Finally it ended under the Peace

of Augsburg (1555) which granted toleration to those princes and subjects who had adopted

the Augsburg Confession, and that the prince determined the religion of his subjects, that

no other form of Protestantism would be tolerated. Protestants were allowed to retain all

the church property received up until 1552. After that date, any priest or prelate who

defected lost his church and land. This latter part was never fully accepted by the

Protestants and it had been added by the Emperor

Lutheranism seemed revolutionary to the Catholics but was conservative

to the left wing of Christianity which believed he had gone only part of the way. Official

Lutheranism seemed too close to Roman Catholicism. They wanted to restore the early church

of first century. They were called Anabaptists by critics, Baptists by themselves. They

argued that people should understand the faith before they could be baptized into it; thus

they rejected infant in favor of adult baptism. To them, the true church was only the

people who have received regeneration of faith and are baptized into the elect. The Church

is not identical with the community at large as Luther believed, but the community of

saints. They became martyrs, refusing to bear arms and take oath in court. Within their

own organization, they practiced strict democracy. All were equal. They had a

communitarian or communist belief. They fought for separation of Church and State, for

religious freedom. Many of these descendents came to the U.S., people who were peasants,

artisans, miners, and especially those affected by the economic change and dislocation

caused by the discovery of the New World. In many of the industrial cities where

Protestantism took hold, the Anabaptists flourished.[68]

Christianity split into two wings, the Right of Roman Catholicism and

Lutheranism, the Left of the Anabaptists/Baptists. Lutheranism kept a good deal of the

medieval church because of the fear of radicals. Lutheranism fought radicals who argued

for the literal meaning of the Bible which few could translate. Anabaptists held two

prominent theories:

1. Second Coming of Christ—immediately

2. Inner voice said that person was saved.

They proceeded to do anything they wanted because it was ordained by God. They were called

antinomians (against the law). The Anabaptist movement climaxed with the uprising at

Münster, 1531-35. Peasants were fighting social conditions. There is a parallel between

the outbreak of the peasant rebellion and the rise of Anabaptist influence. Some

Anabaptists indicted for their part. The suppression was violent. Luther condemned the

Anabaptist movement and the Peasant War whose manifesto was the Twelve Articles.[69] In the Peasants' War, the upper

classes were thrown into panic, and the peasants were hunted down and killed by Lutherans

and Catholics. The Anabaptists turned to quietism and pacifism under the Dutch reformer

Menno Simons[70] and became known as

Mennonites. Some went to Moravia, others moved around. Christian left wing was composed of

many different kinds of people and groups, all rejecting the authoritarian structures of

Roman Catholicism and Lutheranism. Unitarianism appeared.

v The Reformation in England began as an act of state by decision of the

monarch, Henry VIII, to break with the Papacy. This institutional break occurred before

rather than after the doctrinal beliefs. John Wyclif’[71] movement had been stamped out so it was not a cause. The

immediate cause was the desire of Henry to have his marriage to Catherine of Aragón

annulled because he and others believed that she could not give him a male heir.[72] Although he had condemned Luther, he could

not persuade the Pope Clement VII to grant his divorce. When the Pope wouldn't agree,

Henry stripped the Papal Legate, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, from power and replaced him with

Thomas Crammer who helped organize and mobilize public opinion. In 1529, Parliament backed

Henry; Thomas Crammer[73] was appointed

Archbishop of Canterbury and he granted Henry his divorce so that he could marry the

pregnant Anne Boleyn[74]. Unless he had a

male heir, the Tudor line would die out. Furious, the Pope excommunicated Henry.

Henry VIII

Henry VIII

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I

In 1534, England made a complete break with the Church of Rome through

the Act of Supremacy passed by Parliament. It established the King as the head of the

Church of England and that children of his marriage to Boleyn would be the heirs to the

throne. In 1535-36, lesser monasteries were confiscated through the Act for the

Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries. Some of the faithful rose in protest, notably in

the Pilgrimage of Grace in northern England but were suppressed. Henry distributed some of

this property to supporters. Henry was a strong and smart enough ruler to have his way but

he was also aided by the insular and anti-continental attitudes so prevalent.

That the State could force the Protestant movement on the people for

the first time was important for the course of the English Reformation. It was the first

time that such a large unit had broken from Rome; without England, it is doubtful that the

Protestant movement could have lasted. The English state absorbed the Anglican Church. The

Anglican Church has seemed Erastian, for followers of Thomas Erastus believed the church

should be subservient to the State. Change occurred with relatively little bloodshed.

Thomas More and others were killed for heresy. What were the reasons for the non-violent

acceptance of this change?

l. Recent memory of the violence of the War of the Roses.

2. Henry's caution and ostentatious respects for the forms of legality

3. Skill with which he appealed to nationalism, and to anti-clerics, for backing of the

divorce question.

4. Henry retained the Catholic liturgy and sacraments

5. Confusion over actual issues; few knew what was happening and most would not want a

complete break.

Regardless, Henry had released powerful new forces by substituting himself, a secular

person, as head of the Church. The Church of England tried to stay close to Catholicism

but with important difference. It used an English liturgy. Priests, who married before the

12th century, could once again marry. The Six Articles (l539) placed

Anglicanism on record as true to Catholic dogma and required everyone to subscribe to

them. All was not well, however. Archbishop Crammer founded a Protestant faction. When

Henry died, his heir, Edward VI ruled, but he was only 10 years old. Crammer, in the name

of the king, drafted the 42 Articles, a more Protestant doctrine, and had them

enacted. Thus, the Book of Common Prayer was created and it was much more Protestant.

Edward died. Mary I succeeded. The daughter of Catherine, she was Catholic. She married

Philip II of Spain, her cousin. She reintroduced Catholicism with a vengeance earning the

sobriquet Blood Mary by her detractors. Cranmer, after public humiliation in

ecclesiastical and secular courts was burned at the stake in 1536. Hundreds of other

Protestants died. She died after five years on the throne in 1558 and was succeeded by her

half-sister, Elizabeth I, a Protestant. The faithful suffered a heavy burden from these

shifts. Somehow, the mass of Englishmen were able to accommodate themselves to the

shifting theological lines. Many were fearful of transgressing against the king but many

simply did what their neighbors did.

John Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin (1509-1564) shaped

Protestantism more than any single person. Whereas Luther was the ground breaker, Calvin

was the systematizer and organizer of the movement. He thought logically, rationally.

Calvin built upon Luther's work. They shared five basic Protestant

beliefs:

1. salvation by faith alone

2. salvation only by grace of God

3. the priesthood of all believers

4. the Bible as the sole authority concerning faith and order

5. Glory to God alone.[75]

Calvin borrowed and leaned heavily upon the writings of St. Augustine

of Hippo (354-430), who had developed the doctrine of original sin, the concept that

humans are naturally selfish.[76] Calvinism

became a distinct form of Protestantism, the militant form of European Protestantism. As

Puritanism it left an indelible imprint on English in America. Calvin, a humanist scholar

and lawyer, wed his fine Latin and French style to his legal turn of mind. He converted to

Protestantism about 1533. On a chance visit in 1536 to Geneva, he

met William Farel[77] who induced him to stay

and help spread the gospel in that city. Talented in organization and administration, he

inspired great loyalty but also hatred. His system and organization were different from

Luther because he built out of experience in commercialized town. Calvin didn't sit down

to write a blueprint for middle class in his Institutes of Christian Living (1536).

He created a highly organized church when he returned home in 1541. The combination of

scholarly and practical ability is rare.

The Institutes were translated into every

European tongue. Calvin's church in Geneva was model for reform churches in France,

Netherlands, parts of Germany, and elsewhere. His theology spread across Europe but did

not succeed everywhere. From the middle of the 16th century onwards, Geneva was

the fountainhead of Protestant training, the Protestant Rome, supplanting Wittenberg.

Calvin excluded free will entirely in his theology for he believed in

the absolute sovereignty of God, the Almighty God, the omniscient God, the timeless,

limitless God who determined that all men would inherit the original sin of Adam and set

Jesus upon Earth to redeem Man. He has already determined who will be saved. Time is a

human construct and constraint and therefore ungodly. Calvin argued the concept of

predestination[78]. The Bible, the authority

and the beliefs of the elders of the church became the authority of Christian living for

Calvin. (The Latin word for elder is Presbyter, hence Presbyterian). Asceticism in

selection of worldly goods and desires was valued. Calvinism chose those which would

further salvation as being good such as marriage and the market. One should serve by doing

well in one's calling. Calvin stressed ethical improvement; he believed in a high moral

code for everyone; this led to the desire to suppress bad conduct in others. He did

believe in the method of persuasion as method of salvation. He was not

anti-intellectual. First Calvinists could not be called rational.

Calvinism raised, to a high pitch, the tension which exists between

individual and higher authority. It had to stress some individualism, arguing that people

had to give up obedience to the Roman Catholic Church. He encouraged the competition of

businessmen. Calvinists had to defy civil authority in England, France, Scotland,

Netherlands, Poland, Hungary, and Bohemia. The individualism of Calvin could be

overemphasized. In 16th century Geneva and 17th century Boston, a

minority of officeholders—clergy, teachers, elders, and deacons—ruled. The

economy as well as the social contact was regulated. These were societies of status and

oligarchies; ministers and magistrates (Boston) and ministers and elders (Geneva) had high

status. Its form of church government was the election of minister and elders by the

majority. Calvinism emphasized the separation of Church from State, an educated clergy,

and the militant people of God, very much like the medieval church of the Crusaders. It

preserved some Catholic traditions akin to the Middle Ages. In 1559, he published the

definitive edition of The Institutes and founded the University of Geneva. The

first national synod met in France and the religion became rooted in the Netherlands and

Central Europe. There seemed to be no stop to Calvinism.

The Pope and fellow believers launched a counter reformation to bring

people back into the fold of the Church of Rome. About half of the Europeans had defected

to Protestantism, a severe blow to Catholicism. The northern third of Europe became

Protestant but the subversion of the Church’s teachings and defections occurred in

such areas as France, Poland, and the British Isles, even in parts of Ireland. So the

Church went on the offensive. The clergy became more pious and encouraged the people to do

so as well. The Papacy made a number of institutional reforms and changes in

administration and dogma. There were a remarkable number of Catholic saints created in

this period—Pius V, Thomas More, Francis DiSalle, Theresa. Some of the saints founded

new orders. Phillip Neri[79] founded

the Oratory of Divine Love[80] in Rome which

gathered together for prayer and singing music (sacred). “Reformation of Church and

Society begins in one's soul” was the mantra. It contributed leaders to the Council

of Trent. Charles Barromeo[81] founded the

Order of Oblates who placed themselves under the Pope directly. The faith of Spanish

Catholics kept vivid by attacks on Moors and Jews.

The most influential figure of the Catholic Reformation was Ignatius

Loyola, founder of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). He was a soldier for Charles V in Spain

who suffered an leg injury and was hospitalized at Manresa. In 1522, he underwent a

conversion and vowed to become a knight of Christ. Whereas Luther believed that sin was

inherent in man and only God could save man, Loyola believed that Satan (sin) was apart;

that man had the ability to choose between God and sin; and by his imagination, man can

reinforce his will and make a decision for Christ and resist Satan. He wrote a volume

called Spiritual Exercises (1548). The Society of Jesus (1540), endorsed by Pope,

revealed the military sympathies of its founder; its members take special vows to the Pope

in addition to the vows of poverty, charity, and celibacy. Jesuits did not make strenuous

ethical demands upon their converts; the goal was numbers. They saw education as the way

to influence minds so they became educators. In that era, it meant educating the elite,

the only ones who went to school. They were able to influence key people by becoming

confessors to the monarchs and nobility of Europe. In central Europe, they were the

commandos of the counterreformation bringing Poland, southern Germany, and Bohemia back

into the Catholic fold.

Beginning with Paul III[82]

(1534-49), men of responsibility became Popes and appointed Cardinals of like quality.

Popes and the Council of Trent reformed the Roman Catholic Church. Council of Trent met in

three separate sessions from 1545-1563. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, strongly advocated

the Council. The Popes feared that the Council would shear them of their powers, so they

managed to control the vote, using the Jesuits to guide discussions. The Council concerned

itself with dogmatic definition and articles of reform. The articles of faith were sharply

defined and made dogma, to wit, salvation by faith and good works but with a little more

emphasis on good works, penances, and sacrifices. The Council asserted that authority was

not in Bible alone but also in the Latin Vulgate Bible as interpreted and understood by

the Church and according to the traditions of the Church. Seven sacraments, including

transubstantiation, were confirmed. Saints were to be venerated; a practice which most

Protestants believed was treating humans as lesser deities. The practice of granting

indulgences was upheld but no longer on a monetary basis. Other moral prohibitions

adopted—the sale of Church offices, ordering prelates and bishops to live in their

dioceses, more training of priests in seminaries. It was an ecumenical reform, that is,

all of the Catholic churches. The net result was that the Church closed ranks,

reformulated essential dogma, instituted some of moral and institutional reforms demanded,

thereby saving half of Europe from becoming Protestant Christian. The medieval Inquisition

was revived in Spain and Italy. Index of Books began in 1559 by body

called the Body of the Index of the Cardinals. The Roman Catholic Church reasserted its

independence from lay rulers and regained much of the prestige lost in the high middle

ages.

The Catholic and Protestant Reformations tended to hurt secular

progress. Some assert that Martin Luther revived the Christian consciousness of Europe;

people were willing to die for their faith. Life was becoming permeated with secular ideas

when this happened. At this very point there was the great religious revival. By 1550,

Calvinist Church and Jesuits led the way in a supranational and supernatural drive

demanding allegiance to Christianity transcending secular bodies and nationalism. The

clashing of these influences with secular force gave the latter 16th century

its significance, characterized as a struggle between deep-seated dynastic national power,

on the one hand, and religious armies, on the other.

Western Christianity, i.e. the version based in Rome had been tied to

secular rulers since it became the state religion of the Roman Empire. After the Empire

had split into different parts, some small, some large, the secular rulers still tried to

control the religion in their realms even though they claimed to be members to believe in

a single, universal church, the Church of Rome. The Pope and kings made deals as to who

controlled the appointment of church officers and which church doctrine would be spread in

a kingdom. A king might be Roman Catholic and resist the Pope. He acted in what he thought

his self interest was. When it was to his advantage he would become Protestant or ally

with a Protestant ruler or become an ally of a Muslim ruler. The Protestant Reformation

revealed these issues.

The first half of the 16th century was a period of dynamic,

dynastic personalities: Henry VIII (1509-47) of England, Francis I (1517-1547) of France,

Suleiman (1520-1566) of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, and Charles V (1519 -56) of the

Hapsburg Empire. Charles V is the central figure because of the location of his dominion

in Central Europe.

Spain

Under Francis I (1507-47) and Henry II (1547-1559), the French monarchy grew stronger. In

1559, however, Henry II died in a tournament (France was still participating in forms of

chivalry), leaving three weak sons and his despised wife Catherine of Medici. His death

seemed to be signal for political, religious, and social battles to break loose. The

kingdom was kept in civil war for forty years. It became an arena for the contending

forces of manorialism/feudalism versus centralism with Spanish intervention and English

intervention. France fell to being a second-rate power, ineffective as a European power.

Francis I

Francis I

Charles V of the

Holy Roman Empire

Charles V of the

Holy Roman Empire

Charles V (Charles I of Spain)[83]

headed a large unwieldy empire, controlling much of central and Western Europe as well as

Latin America. His dominions came to him through marriage, inheritance, and the Hapsburg

luck in acquisition. He was heir to Hapsburg dominions and Low Countries. He had

possession of Italy and Spain and the New World. He came into his inheritance in two ways.

Spain, the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, and later Milan came when grandfather, Ferdinand,

died. When his other grandfather, Maxmilian, died, he got Hapsburg lands in the Germanies.

He got himself elected Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. This was a formidable empire on

paper. Charles had wealth of Flanders and gold and silver from Peru and Mexico. His

soldiers were the best fighting force in Europe. The very size of his army was a threat to

the balance of power in Europe.

The Hapsburg-Valois War (1522-59) demonstrated some of Charles’

problems. The French Valois monarchy, the only other monarchy as strong as the Hapsburgs,

began to attack Charles V to prevent Hapsburg hegemony while, at the same time, Lutherans

were fighting him for religious reasons. Charles and Francis, the French king, were

long-term bitter rivals. Francis had been beaten out for Holy Roman Emperor by Charles.

Their armies clashed in the Paria Valley of Italy in February, 1525; Francis I was

captured. He was released in 1526 when he signed the Treaty of Madrid which required him

to give his two sons as hostage. Once freed, however, he repudiated the treaty and

launched the War of the League of Cognac (France, Pope Clement VII, the Republic of

Venice, England, the Duchy of Milan and Republic of Florence). That league failed so he

allied with the Muslim Ottoman Empire to fight another Italian war (1536-38 with Charles.

Francis lost again and lost still again in another war. The rapid revival of the French,

however, showed the weakness of Charles' empire. He had to expend time, money, and energy

holding on to what he had and could not go in for the kill. He never went to conquer the

world but followed a conservative policy.

Ruling was not easy. The Spanish did not want Charles because he was

not Spanish but Flemish. He fought numerous religious wars against Protestants. Most

threatening of all were the Ottoman Turks who were marching westward and defeated the

Christians at Mohács in Hungary in 1526. By 1529, they were at the gates of Vienna, which

alarmed Christendom. The fortifications of Vienna held and the Turkish invasion receded.

For 30 years, until his abdication in 1556, he was fighting somewhere in his

domain. Charles couldn't solve his domestic political problems, his Turkish and French

problems, and the religious problem.

By the 16th century, Europe was a network of political

relationships that a war or heresy or economic change or other factors in one part could

cause repercussions everywhere. Europe was never unified in terms of religion; after all,

some of its people were Jewish, Muslim, atheist, Wiccan, and any number of religions, but

the vast majority asserted that they were Christian and it was Christianity the defined

European civilization. Europe lost its spiritual unity. There were struggles for power and

clashes of religious ideologies in the years 1501-1600. The European economy was subjected

to strain by the inflationary effect of gold and silver pouring into Spain from New World.

Prices tripled. Inflation spread into the “four corners of Europe” and was

followed by social distress. Those on fixed incomes (such as the older nobility and urban

workers suffered. It adversely affected persons who had no way of increasing their income

such as peasants. Such people attempted to hold down the prices of necessities. A new