|

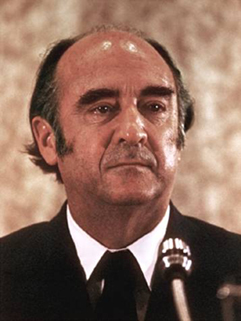

Mexican Snake: José López Portillo

The conservative political savior José López Portillo[1] assumed the Presidency on December 1, 1976 after the tumultuous, populist,

and extravagance of the Luis Echeverría presidency. On November 30, 1982, six years

later, he left in disgrace; many, perhaps most Mexicans, considered him a snake, a man who

had feathered his own nest while damaging the country by fiscal irresponsibility,

corruption, and demagoguery. He spent much of the rest of his life in exile but went back

to Mexico and died on February 17, 2004 at the age of 83.

There were those who said he never should have become a

politician but remained a member of a well-respected family, a university professor, an

author, and a philosopher. Perhaps it would have been acceptable to become an

administrator at the sub-cabinet level of the national government, for these did not

require the political skills of a President. But he rose beyond to become Secretary of

Treasury, 1973-75, and then President, 1976-82.

He was born on June 16, 1920 in Mexico City. His father, José

López Portillo y Wéber, was a soldier, engineer and historian of middle-class status,

far above the average person. His paternal grandfather, José López Portillo y Rojas was

a distinguished intellectual and member of the Mexican Academy who served in the cabinets

of two conservative governments. He was proud of the fact that he was the

great-great-great grandson of José María Narváez (1768–1840), a Spanish explorer

who was the first to enter Georgia Strait in present-day British Columbia. The future

president was born as somebody but not rich. He graduated from public schools in Mexico

City, including the National University which he entered in 1939 and from which he

graduated in law and political science in 1946. Part of his university education was

obtained at the University of Chile with the aid of a scholarship from the Chilean

government. He obtained his law degree in 1946.

He married his childhood neighbor, Carmen Romano, in October,

1951. They moved into a three-storey house given to her by her father. She bore him three

children--José Ramón, Carmen Beatriz, and Paulina. The couple were separated but

reunited for the sake of appearances when he was designated the Partido Revolucionario

Institucional (PRI) presidential candidate in 1975 for the campaign and the duration of

his presidency. She performed the public duties of First Lady, mostly entertaining

dignitaries and doing good works. She created the National System for Integral Family

Development (a social assistance agency for families), and various programs to promote the

arts. Nevertheless, the couple maintained separate lives throughout his presidency and

physically separated again once he left the presidency. They divorced in 1991.

The young man became a successful lawyer and a professor of law

at his alma mater the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in 1947, remaining

in that role until 1958. His textbook on the general theory of the state earned him extra

income. He wrote a book about the Mexican feathered serpent god Quetzalcóatl in

1965 and then, in 1975, a philosophical novel, Don Q. , wherein he waxes

philosophical about figurative as opposed to literal meanings in life. In 1961, after he

founded the doctorate in Administrative Science in the business school (Escuela Superior

de Comercio y Administración (E.S.C.A.) in the National Polytechnic Institute. He seemed

the stereotypical academic--teaching, writing a textbook, involving himself in academic

administration--as well as being a novelist, painter, athlete, and equestrian. He was an

attractive, charming man of virtu.

Perhaps he entered public service in 1959 at age 39 because of

his childhood friendship with Luis Echeverría Alvarez, a rising politician who would be

President, 1970-76. They had played together as boys; enjoyed a friendship at UNAM

students where they both worked on the school newspaper in 1940; traveled together on the,

long voyage to Santiago, Chile where they studied on a fellowship in 1941; and continued

their friendship after receiving their law degrees. Although It was common for a lawyer to

practice law, teach part-time, and work at a low level national government job, he

abandoned the law practice as he rose in government ranks.

His government career before becoming President in 1976 is

briefly summarized. From a low post, he rose to the Cabinet in fourteen years. He was seen

as an amiable, connected, technocrat or, at least, someone who could manage technocrats.

- 1959--Technical Advisor, Secretary of National Heritage.

- 1960-65--Director General, Federal Commission for Material Improvement in the Secretary

of National Heritage.

- 1965--Director General, Juridical Consultative Office, Secretary of the Presidency.

- 1966--Member, Joint Secretarial Commission (Treasury, Presidency) to formulate

developmental plans.

- 1968-70--Subsecretary of the Presidency.

- 1970-72--Subsecretary of National Heritage.

- 1972 (August) 1973 (May)--Director General, Federal Electric Commission.

- 1973 (May)-1975-- Secretary of Finance and Public Credit [Treasury]

Understanding the Echeverría regime (1970-76) is

imperative to understand the López Portillo presidency. President Echeverría tried to

become a hero to the average person in the mode of President Lázaro

Cárdenas (1934-40) after the hard-line, iron fisted conservatism of his predecessor,

Gustavo Díaz Ordaz under whom he had been Interior minister, responsible for domestic

politics and security. As such, Echeverría had ordered the repression of the Student

Movement of 1968 and was responsible for the Tltatelolco Massacre of October 2, 1968 just

before the Mexico City Olympiad . As Jim Tuck remarks:

[He] released students who had been arrested after Tlatelolco. ordered rigid price

controls on basic commodities, added a 10 percent tax to luxury items and a 15 percent

surtax to bills in first-class restaurants and nightclubs, increased subsidies to

universities and technical institutes and gathered the highest percentage of National

Autonomous University (UNAM) graduates (78 percent) in his cabinet.[2]

He tried to help the rural poor, regardless of cost, creating some 17 million more ejidos

(communal farms) partly by expropriating rich, irrigated lands in Sonora and Sinaloa

states. Money was poured into rural credit banks and ejidos received preferential

treatment. Echeverría thought it could jump start economic development among the rural

poor and increase agriculture production simultaneously. He was wrong, very wrong. Mexico

had to import foodstuffs.

When his Treasury Secretary, Hugo B.

Margáin, balked at borrowing more money, domestically or externally, to finance

federal government programs, he was dismissed an sent to London as Ambassador and the

pliant López Portillo was put in his place in May, 1973. López Portillo had no qualms in

doing what his friend wanted. He found the means to finance the programs of his friend.

Although he did improve the tax collection system, he continued borrowing vast sums.

Petroleum played a key role in both the

Echeverría and López Portillo because Mexico was an oil-exporting nation during the

decade that crude oil prices skyrocketed. The first jump in oil prices came with the Oil

Crisis of October, 1973 when the conservative Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting

Countries embargoed petroleum exports to the United States. They were angry because the US

supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War against some of its members. Oil prices skyrocketed

from $3 a barrel to almost $12 a barrel by March, 1974, creating inflation and recession

in countries allied to the United States. Mexico was the third largest trading partner of

the US and the US was, by far, its largest trading partner. Quadrupled oil prices helped

Mexico at first and enabled its government to borrow funds but Mexican dependency on the

gigantic US economy created problems as American spent less in Mexico. By the time José

López Portillo took over on December 1, 1976, the peso had dropped in value from 12.5

pesos per dollar to 20 pesos per dollar and the external debt had risen from $6 billion

dollars in 1970 to $20 billion dollars in 1976.

López Portillo became president without significant opposition

once Echeverría had chosen him but he campaigned throughout the country so people could

see the next president and to touch base with the various politicos in the PRI. He was

seen as a conservative technocrat who would stabilize government finances and the economy

not as a politician. No one doubted he would “win”—the PRI candidate was

always the winner—but the National Action Party (PAN) fought within itself over

ideology and over the efficacy of running a presidential candidate and, thus, supporting

the sham.

In the first few years, he and his

administration did all the right things to stabilize Mexico. He effectively let others

know that he was his own man, that Echeverría was the past president. He reassured

the business community. He persuaded labor to moderate its wage demands while encouraging

business and industrial leaders to cooperate with labor with the Alliance for Production

(Alianza para la Producción). He reorganized cabinet agencies. The Secretary of Budget

and Programming replaced the Seceretary of the Presidency. Agriculture and Water Resources

were combined. The Secretariat of Natural Resources and Industry was created. He planned

to cut the budget deficit from 9% of the Gross National Product in 1976 to 6% in 1977 and

then to 2.5% by 1979. Taxes were increased on excess profits, luxury items, motor

vehicles, some incomes. Price controls were extended on basic foods. Some drug prices were

decreased by 60%. López Portillo’s administration saw the inflation rate drop in

half from 30% to 15% by mid-1977. The economy grew only 2% but it grew.

To curry favor with the Mexican left, he

had a political amnesty law passed. In an unprecedented move in an anticlerical country,

he received Pope John Paul II in January, 1979; the Pope celebrated a open air mass. The

Mexican Constitution forbade public religious ceremonies.

One of his greatest achievements was to

move Mexico towards democracy by enlarging political participation The Federal Law of

Political Organizations and Political Processes of 1977 lowered the number of members a

political party needed to run candidates in elections. Alternatively, a party could get

conditional registration to run candidates which would become permanent registration if it

received 1.5 percent of the national vote. The minority parties gained from free

television and radio time. The lower house, the Chamber of Deputies, was enlarged by

constitutional amendment to 400 members, 100 of which would go to minority parties on a

proportional representation basis. PRI maintained hegemony, however. As Joseph Klesner

notes, the reform probably fragmented the opposition left.[3] On the other hand, PAN, the center-right party, gained seats and national

attention.

López Portillo lost his perspective when

vast petroleum reserves were discovered in 1978 in the Gulf of Mexico. By the beginning of

1979, proven reserves were 26 billion barrels with possible reserves of 100 billion

barrels. Mexico was suddenly in the same class as Saudi Arabia. As he said, “"In

the world of economy, countries are divided in two: those that have oil and those that

don't have it. And we have it!" “In 1981, Mexico became the fifth largest

oil-producing nation with daily production of 2.3 million barrels (scheduled to be 2.7

million in 1981). López Portillo announced that proven reserves stood at more than 60

billion barrels, an increase of more than 20%. Oil exports, primarily to the United

States, earned more than $12 billion as Mexico raised its prices in tandem with OPEC.

Natural gas exports to the United States (300 million cubic feet per day) were priced at

$4.47 per thousand cubic feet in an agreement signed by both nations in March.

Profits from oil boom and monies borrowed

massively based on those profits, present and future, were spent on investments in

economic development projects regardless of merit. Incomes rose legally and illegally. The

flow of money into Mexico overwhelmed accounting system, not that López Portillo cared.

The Gross Domestic Product grew at the rate of 8% a year in the last years of the decade,

surpassing the 6% rate of the years of the Mexican Miracle.

The President believed he could end rural

poverty and meet the nation’s needs for food and fiber with oil money. Mexican

agriculture was unable to supply the nation’s needs; by 1980 Mexico a net food

importer. So López Portillo emphasized production of basic foodstuffs for domestic

consumption by creating the Mexican Food System (SAM). It sought to help small farmers

grow more food for the domestic market while also subsidizing a “basket of staples to

19 million undernourished people. SAM was to be financed by oil revenue and international

borrowing, something which could not be sustained by the economic crisis of 1981-82.

President Miguel de la Madrid ended the program in 1982.

Mexico became more independent of the

United States in foreign policy. López Portillo proposed a World Plan for Energy

Resources to the United Nations. He sponsored a North-South Summit in Cancún in 1981 to

promote dialogue between First and Third World countries. Fidel Castro, the Cuban

dictator, was received warmly, much to the displeasure of the United States. He

reestablished diplomatic relations with Spain, broken since the fascist Francisco Franco

came to power in 1939.

He appointed relatives to important

positions. His sister, novelist Margarita López Portillo, became Director of Film, Radio

and Television. His son, José Ramón, became Undersecretary of Programming and Budget.

The President bragged “¡Mi hijo es el orgullo de mi nepotismo!” ["My son

is the pride of my nepotism"]. The Los Angeles Times asserted that Rosa Luz

Alegria was his mistress when he was President and that he made her Minister of

Tourism. [4]

López Portillo and his advisers were

betting on the “never never’, that international oil prices and international

demand for oil would remain high or increase, allowing Mexico to finance its needs and

desires regardless of what happened to the United States economy. They thought that oil

made Mexico free, finally, that the US needed Mexico more than Mexico needed the US. They

were wrong. The United States economy determined Mexico’s economy.

In the United States,

“stagflation,” the continual rise in prices combined with slow economic growth

and higher than usual unemployment, was fueled by the quadrupling of oil prices in 1973-74

and its fallout. In the post-WWII period, inflation had averaged 3.2% but reached a 7.7%

rate after the Oli Crisis. Then it rose to 9.1% in 1975. By 1979, it had risen to 11.3%,

then to 13.5% in 1980. It fell from 10.3% in 1981 to 3.2% in 1983. Automobile prices

increased 72% between 1973 and 1979. New house prices went up 67%. In 1979, because the

Iranian Revolution interrupted that nation's production of petroleum, gasoline prices

increased 60%. High unemployment continued. Investment, savings, and productivity

declined. Carter advocated and got the deregulation of many businesses and industries in

hopes of stimulating business and industry but these measures had no apparent immediate

impact.

Stagflation in the United States and

other Western nations reduced the demand for oil and, in 1981, they fell precipitously.

Paul Volker, Chairman of the Federal Reserve System, began forcing interest rates upwards

in 1979 to combat inflation.

Mexico was hit with a double whammy. Its

income dropped at the same time its service increased on its $60 billion external debt.

López Portillo swore publically that he would defend the peso “like a dog”. It

plunged in February, 1982 from 22 to 70 per dollar, or 78%, the steepest drop in Mexican

history. The President was often met thereafter by barking. Devaluation meant, of course,

that more pesos would be necessary to pay the dollar-denominated external debt. Richard

Boudreaux noted: “By 1981, when the oil boom went bust, 87 cents of every dollar of

assets held by PEMEX, the state oil monopoly, were owed to foreign banks. The debt was

one-fifth of the country's total foreign debt. And in the month before the peso collapsed

in August 1982 by 60%, a crisis of investor confidence sent $9 billion out of the

country.” Mexico had to default on its debt and give up some freedom of action in

order to get emergency aid from the United States and international agencies.

In a fit of fury, López Portillo

announced the nationalization of the banks in September, 1982. In his State of the Union

address, he blamed the banks for Mexico’s financial ills, saying that they had aided

and abetted the capital flight. He broke down in tears, begging the forgiveness of

Mexico's impoverished millions. They didn’t. He finished out the remaining three

months of his term in disgrace.

The new President, Miguel de la Madrid

Hurtado, was a sober, conservative, technician with a master’s degree in public

administration from Harvard. He promised a moral renovation in the government and a few

visible people were prosecuted He resisted efforts to punish his processor, letting him go

quietly into exile in Europe. Perhaps some house cleaning occurred at lower levels. He

would reverse much of what López Portillo did, including the bank nationalization,

restoring confidence in the business and industrial communities. Mexico would join GATT,

opening the Mexican economy to competition.

Away in Spain, López Portillo

defended his political and economic actions including an autobiography but continued an

unconventional personal life. He lived with his Mexican mistress, Alegria, and divorced

his wife, Carmen in 1990. After he and Alegria split, he married retired Yugoslavian-born

film star Sasha Montenegro in 1995 and had two children with her. They returned to Mexico

in the late 1990s but separated years later. His health worsened. Double bypass heart

surgery in 2001, ulcers on his legs in February, 2003, and respiratory and heart problems

when he was admitted to Angeles del Pedregal Hospital in February, 2004. He died at 8:15

PM on February 17, 2004, surrounded by some fifty relatives and close friends.

His obituaries blamed him as a corrupt,

incompetent. As it were, a snake. López Portillo had become very rich while in office

according to popular lore. Not only had e bought an expensive mansion for his mistress but

was able to replace it with another when his wife confiscated the first. Before he

finished his term, he built a five mansion compound on a hill overlooking Mexico City,

“dog hill” as wags called it. Many claimed that he became a billionaire[5] while in office. He was able to live in

Europe. He certainly acquired money from somewhere; he was not rich before becoming

President.

Perhaps his fascination with

Quetzalcoatl, the Toltec feather serpent and god-king encouraged that view, a mocking of

his artistic and intellectual interests. He certainly had dreamed big, of making Mexico

less dependent upon the American behemoth, of using oil revenues to develop the nation

over the long-term for a sexenio was too short a time. Quetzalcoatl, was driven out; so

was López Portillo.

The United States was in economic

difficulty for more than the decade of the 1970s and its conservative leaders could not

solve the problems. How was Mexico expected to do better? If the world economy had not

gone into a tailspin in 1981 and petroleum prices had not plummeted, López Portillo might

have won the bet. But Presidents are not supposed to gamble on such a scale. López

Portillo did to his everlasting shame.

Donajd J. Mabry

060410

__________

SOURCES:

Alexander, Charles, Jay Branegan, and Laura López, “A Freeze Play at the

Banks,” Time, September 13, 1982.

Anonymous, “Carmen Romano,” Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmen_Romano.

Boudreaux, Richard , “Jose Lopez Portillo, 83; Former President Led Mexico in Boom

and Bust,” Los Angeles Times, February 18, 2004.

Cárdenas, José, “Niega López Portillo recibir pensión millonaria,”

Noticieros Televisa, agosto 14, 2003.

Central Intelligence Agency, “Outlook for Mexico,” April 25, 1984.

Cuellar, Mireya , “Corrupción, frivolidad y despilfarro, ejes del sexenio

Lopezportillista,” La Jornada, February 18, 2004.

Kate Doyle, Prelude to Disaster: José López Portillo and the Crash of 1976

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 115, March 14, 2004.

Escalona, Ivan, “José López Portillo,: monografías.com.

http://www.monografias.com/trabajos12/hmlopez/hmlopez.shtml

Fisher, Swayze, “José López Portillo and The Financial Crisis of 1982,”

Historical Text Archive, 2002. http://historicaltextarchive.com/sections.php?action=read&artid=554.

Kandell, Jonathan, “José López Portillo, President When Mexico's Default Set Off

Debt Crisis, Dies at 83,” New York Times, February 18, 2004.

Klesner, Joseph , "Electoral Reform in Mexico's Hegemonic Party System: Perpetuation

of Privilege or Democratic Advance?" Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American

Political Science Association, Washington, D.C., 28-31 August 1997. http://www2.kenyon.edu/Depts/PSci/Fac/klesner/Electoral_Reform_in_Mexico.htm.

Mabry, Donald J., Mexico,” Americana Annual, 1973-1984.

Tolchin, Martin, “Paradox of Reagan Budgets: Austere Talk vs. Record Debt,” New

York Times, February 16, 1988.

Tuck, Jim, “Black gold, fool's gold: the oiling of a crisis (1938–1988), “

Mexico Connect (http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/297-black-gold-fool-s-gold-the-oiling-of-a-crisis-1938%E2%80%931988).

Watkins, Thayer, “Financial and Economic Crisis in Mexico in 1982,

“http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/mexico82.htm.

Notes

[1] José López Portillo y Pacheco is his full

name but he was known as José López Portillo.

[4] Richard Boudreaux, “Jose Lopez

Portillo, 83; Former President Led Mexico in Boom and Bust,” Los Angeles Times,

February 18, 2004. Jonathan Kandell, “José López Portillo, President When Mexico's

Default et Off Debt Crisis, Dies at 83,” New York Times, February 18, 2004, asserted

that he bought her a $2 million mansion in Acapulco and then another villa after his wife

too the Acapulco dwelling.

[5] He contended in 2003 that he lived on an

annual pension of about 1,723, 000 pesos ($158,656 in 2003).

Donald J. Mabry

|