3: The Sea and Chilean Expansion

<< 2: Independence || 4: Civil War >>

The War Against the Confederation

After Chiloe the dismemberment of the squadron was almost complete. The only ship left

was the Aquiles, the very brig that had served the Royalist Quintanilla

and which had been taken over by Pedro Angulo in Guam. She participated actively in the

unsettled activities that marked the first few years of republican life in Chile. Since

the government owned only one ship, when Aquiles was at one time taken

over by revolutionaries, the authorities had to ask for help from outsiders. Once the

English man-of-war Thetis pursued and captured the brig and return her to

Valparaíso. Fortunately the regime established by Diego Portales, the very able minister

of President José J. Prieto, in 1833 brought about a period of calm, progress, law, and

order. The navy was increased with a few small vessels that were used for internal

commerce, scientific exploration and mapping the most important harbors and passages. An

expedition was sent to the Juan Fernández Islands carrying the French scientist, Claudio

Gay.

But Portales had powerful enemies outside of Chile. In July of 1836 General Freire, was

living in exile in Peru. With the help of General Santa Cruz, 'Protector' of the newly

created Peru-Bolivian Confederation, Freire armed a small squadron in Callao and sailed to

promote a revolution in Chile. One of his ships, the frigate Monteagudo,

mutinied and sailed into Valparaíso where the crew turned themselves into the

authorities.

Freire sailed on to Ancud and through a ruse obtained the surrender of the town. A few

days later Captain Manuel Díaz arrived with the same frigate Monteagudo

which Freire thought had been delayed only by the weather. Díaz easily captured the town

and arrested Freire.

Portales did not wait for the return of Díaz or for the trial of the captured

officers, but ordered the Aquiles to Callao carrying as many men as could

be accommodated. The brig arrived off Callao on August 21st and that very night 80 men in

five boats entered the port of Callao. Under command of Pedro Angulo the assault force

boarded all of the Confederation's ships so easily and quietly that the local authorities

did not realize until next morning that the Aquiles set sailed away

carrying with her the Confederation's navy!

An attempt at mediation was made by the neutral naval commanders at Callao but the

senior Chilean officer, Army Colonel Victorino Garrido refused to give back the ships and

sailed to Valparaíso with the Arequipeño, Peruviana and Santa

Cruz. On arrival they joined the frigate Valparaíso which had

been purchased by the Chilean government. The squadron was placed under command of Admiral

Blanco Encalada, who sailed to Peru with instructions to present General Santa Cruz with

certain Chilean conditions. The Confederation leader refused Chile's terms, which included

the dissolution of the Confederation, recognition of the Peruvian debt to Chile and

reduction of the Peruvian army and navy. Blanco Encalada returned home and prepared his

ships for war. On December 28, 1836 the Chilean Congress declared war against the

Peruvian-Bolivian Confederation.

A revolt by the Maipo Regiment resulted in the arrest of Portales, who was inspecting

the troops. It was crushed by Blanco Encalada who led the loyal troops when the

revolutionaries attempted to attack Valparaíso, but in the turmoil created before the

battle a junior officer had Portales shot. The murder of the Prime Minister was believed

to have been engineered by Santa Cruz. Chileans of all social levels now accepted the war

in the cause of justice.

Blanco Encalada, like Cochrane before him, blockaded Callao and tried to capture or

destroy whatever ships the Confederation had left. The brigs of Santa Cruz took refuge in

Guayaquil, a neutral port where the Chileans could not attack them. Blanco Encalada

divided his squadron: while two ships covered the mouth of the Guayas, the rest blockaded

Callao. Santa Cruz had purchased two excellent corvettes and hired crews to man them. The Libertad

had a Chilean officer, Lieutenant Leoncio Señoret who was assisted by the Peruvian Manuel

Uraga. Once at sea, they arrested the officers loyal to Santa Cruz, took command, and

sailed to Chile. The ship was sent off to Australia to deliver General Freire into exile

in Sydney.

The squadron was then ordered to Valparaíso to embark the army but in doing so it

lifted the blockade of Callao. A Peruvian squadron under command of the Colombian Trinidad

Moran appeared off the coast of Chile; and although it captured a merchant brig near San

Antonio it returned to Peru without causing further damage or worry.

Near Islay the Chilean squadron and the Peruvian squadron met. Cannonades at long range

were exchanged but the Peruvians disappeared into a fog bank. Arriving at Callao, the

Chileans reestablished the blockade while Captain James Bynon in the Libertad

captured the corvette Confederacion.

At Callao feats reminiscent of Cochrane were accomplished. The chief of blockade,

Captain Carlos García del Postigo, ordered a night attack by launch which captured or

burned all the Peruvian ships in port. The Chilean army under command of General Manuel

Bulnes occupied Lima only to find, as did San Martín, that control of the capital did not

mean control of the country. General Bulnes was forced to evacuate Lima and follow the

enemy forces into the interior. The Chilean squadron moved north to keep supply lines open

for the army. In a colossal mistake the navy lifted the blockade of Callao.

With Callao once more open, Santa Cruz , who reoccupied Lima, organized a privateer

squadron under the command of a French officer, Jean Blanchet. Blanchet sailed from Callao

and at Casma Bay found three Chilean ships loading firewood. Commodore Robert Simpson had

taken precautions and although his ships were at anchor and part of his troops on land, he

put up a stiff resistance that resulted in the capture of one of the attacking vessels,

the brig Arequipeño ---the same ship that had been captured earlier but

which had been returned to Peru. The brave Blanchet was killed in the attack. The rest of

his ships, although badly damaged, managed to escape into Guayaquil where their captains

took neutral flags. The battle at Casma had put the Chilean crews into a difficult

situation, but their discipline and training had paid off because the men, by now used to

daring boarding and landing attacks, showed equal ability in defending themselves against

a vigorous attack.

The last desperate attempt by Santa Cruz to wrest control of the sea from the Chileans

had failed. A few days later, Bulnes defeated the Confederate Army at Yungay and after two

years and four months of war, the victorius squadron returned to Valparaíso on November

29, 1839.

The Peruvian ships that had been captured or had voluntarily served with the Chilean

navy were returned to Peru. The Chilean ships were sold to private citizens to be used as

merchantmen and only two schooners were left in the service of the government. Once again,

the governing class did not think that Chile needed a navy.

The Merchant Marine

The Chilean merchant marine should have developed parallel to the navy, but its growth

was impeded because of the war. The attacks had been made against nations with which

commerce had been carried on during colonial times. The Talcahuano flotilla was almost

totally lost. The few remaining ships were used as privateers or as transports for the

army and navy. Conditions were such that Chilean sea power deteriorated rapidly.

Once hostilities ended the available ships were so few they could not possible satisfy

the needs for internal or external commerce so the government allowed foreign flag vessels

to trade along the coast of Chile. English ships began to arrive at Talcahuano and

Valparaíso loaded with English and European merchandise to be sold in Chile. They would

then proceed north to La Serena where they would load copper, gold and silver, and from

there went to China or India, from where they sailed loaded with Oriental goods back to

Europe. Some Chileans also attempted this lucrative circuit. The frigate Carmen

managed two trips to the Orient between 1819 and 1820 but the difficulties with the custom

houses in India did not allow great earnings. It was, besides, somewhat ludicrous that

Chileans ships were engaged in exotic trips while their own country was served by

foreigners because there were no Chilean vessels available.

Portales established a policy of protection towards the merchant marine. Naval schools

were created in Valparaíso and Ancud, free storehouses were erected in Valparaíso where

merchants could store their goods without paying customs duties, and financial help was

found for the struggling shipowners. All these measures contributed to raise the number of

ships under the Chilean flag to fifty. But they were not enough to carry on the coastal

agricultural trade and permission was given for foreign ships to engage in commerce along

the coast. These conditions permitted an American, William Wheelright, to establish the

Pacific Steam Navigation Company with English capital. This enterprise introduced steam

navigation into the Pacific in 1839 and eventually grew into one of the world's largest

shipping companies.

The news of the gold discovery in Alta California arrived in Chile on August 19, 1848.

Although Chile had known gold rushes before, the news electrified not only the experienced

miners but all levels of Chilean society. Everybody wanted to reach the golden coast

first. Many abandoned hulks were put into service to make the trip to California with

cargo and passengers.

The English-speaking merchants of Valparaíso were the first to leave, taking their

families and their stock. Large contracts were made to ship merchandise and foodstuffs.

The storehouses created by Portales proved their worth in real gold. Valparaíso shipped

pianos, shovels, pans, pots, nails, and all kinds of tools, while Concepcíon shipped

through Talcahuano the harvest of the southern regions: Chilean wheat would feed

forty-eighters and forty-niners as well as those Argonauts who stayed on into the fifties.

The trip was one-way and soon the bulk of Chile's merchant marine found itself aground

on the mud flats within the Golden Gate. By the end of 1849, 92 of the 119 ships

registered under the Chilean flag were rotting in San Francisco Bay.

The reduction at first, looked like a disaster but in the end it proved beneficial. A

new merchant marine was created with better ships. However, a War with Spain in 1863, to

be discussed later, was to cause the Chilean merchant marine the greatest damage ever

suffered by any Chilean industry: those ships that were not captured, destroyed or sunk,

had to change their flag.

A powerful impulse to the merchant marine was the organization of the Chilean Steamship

Line (Companía Sud-Americana de Vapores) in 1872. It would grow into the largest

steamship company in Chile. Under a government regulation that allowed a subsidy in times

of peace, the company's ships were turned over to the government during the War of the

Pacific (1879-1882). Although their crews were mostly foreigners they served the needs of

the army and navy with diligence and enthusiasm. Not only did these ships transport troops

but landed them under fire and some even participated in combat.

A similar task fell on the ships of the Coronel and Lota Coal Company, whose owners

patriotically turned their ships over to the government without charge, even though they

received no subsidy. The collier Matias Cousiño, named after the founder

of the company, would go along with the squadron in practically every major battle of the

war.

When the War of the Pacific ended, the Chilean coast extended for 2610 miles. New

provinces, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, Arica and Tacna were incorporated and the need to

supply nitrate workers, occupation troops and new civil authorities meant that the number

of ships under Chilean flag multiplied fivefold.

The northern ports were occupied by a never-ending line of sailing vessels loading

nitrate for Europe. Since most of the Chilean ships were used for coastal trading, the

nitrate boom did not have favorable consequences for the Chilean merchant marine. This

situation continued until the l920's. Thus a great opportunity was lost to form a large

merchant fleet which might have placed Chile at the head of maritime power in the Pacific.

In fact the lack of an adequate indigenous merchant marine was one of Chile's most

serious economic deficiencies in the nineteenth century. The country needed ships to take

advantage of the fertility of the central valley which came into full production after

completion of the railroad from north to south, from Santiago to Concepcíon. Nor were

there means to take Chilean products to European markets or to bring back needed

merchandise, so that the majority of the population did not have access to manufactured

goods.

The government tried to implement the development of a merchant navy through tax

concessions, subsidies and other means but Chileans capitalists chose to invest their

money not at sea but in mines, railroads, agricultural properties, and other enterprises.

Soon even the most ardent government officials became convinced that it was better to

leave maritime commerce to foreign owned vessels. The Chilean merchant marine persisted at

barely a subsistence level, struggling to survive.

The War With Spain

The government indifference to a Navy was going to prove expensive. In 1840, the

frigate Chile was purchased in France. She was a beautiful vessel, fast

and armed with 46 guns. But the ship soon had to be disarmed because of lack of funds.

Later, when her services were needed, her timbers proved to have been improperly treated.

When another revolution broke out in 1851, the government purchased the steamship Cazador,

the first steamer commissioned into the regular Navy. Three smaller ships were added and

the small squadron was able to blockade the southern ports until the issue was settled in

a bloody battle at Loncomilla.

The Cazador remained in service until 1856, when sailing from

Concepcíon to Valparaíso with 501 persons on board, she ran onto the Carranza rocks near

the mouth of the Maule river. The shipwreck was inexplicable: the sea was calm, the

weather good, yet only 17 persons survived. It proved to be the greatest loss of life in a

single accident in Chilean history.

Towards the end of the same year, a warship, specially built in England for Chile,

arrived in Valparaíso, the corvette Esmeralda, steam propelled and armed

with 12 guns.

In 1859 Pedro Leon Gallo, a mining leader from La Serena, rose against the government.

The Esmeralda sailed north and bombarded the revolutionaries at Caldera.

The ship was then used as a transport and enough troops were concentrated to attack La

Serena by land. Gallo met them at the foot of Cerro Grande, a hill near the shore. The Esmeralda

approached the beach and fired with decisive results upon the revolutionaries. The

maritime campaign led by Captain José Anacleto GoZi, with the assistance of the Navy's,

three ships, was crucial in transporting and landing troops, and in fire support.

The superiority of the steamship had been demonstrated. The old sailing ships were sold

and the Navy kept just the steamers Maipo, Independencia, and the

corvette Esmeralda. For six years the Navy was able to concentrate on

peaceful missions, such as exploration, transport of troops and passengers, and service to

the new settlements.

In April 1863 a Spanish expedition arrived in Valparaíso. The purpose of their visit

was unclear. While in Chilean waters the officers and men were cordially received and the

Spaniards responded in kind. But once in Peru, the commanding officer attempted to

interfere in Peruvian internal affairs and demanded from the government that some pending

questions be settled immediately. In their dispute, the Spaniards insisted their

representative be a Royal Commissioner and not an ambassador, the latter of which was the

proper title for a diplomatic representative to a free and sovereign state. The Spanish

squadron took the Chincha Islands, the major source of Peruvian guano, blockaded the major

ports, and forced the Peruvian to negotiate. Command of the Spanish squadron was in the

hands of Admiral Antonio Pareja, the son of the Royalist Admiral who died in Chile during

the Wars of Independence.

Anti-Spanish sentiment in Chile was high and when the gunboat Vencedora

coming from Spain stopped at Lota to coal, President J.J. Perez of Chile, declared coal a

war supply that could not be sold to a belligerent nation. The coal embargo could not be

taken as a proof of Chilean neutrality when two Peruvian steamers had left Valparaíso

with Chilean volunteers to fight for Peru. With them went Patricio Lynch, then a young

lieutenant commander who had resigned his commission to join the fight.

Pareja took a hard line and demanded sanctions against Chile that were heavier than

those imposed on Peru. On September 17, 1865, the eve of Chile's national holiday, Pareja

anchored his flagship the Villa de Madrid at Valparaíso and demanded

that his flag be saluted with 21 guns. President Perez realized the demand meant war and

he ordered Captain Juan Williams to depart Valparaíso with the Esmeralda

and the steamer Maypu, with an unknown destination. These orders were

carried out at night without opposition from Pareja. The Admiral lived to regret having

allowed the Chileans to sail away.

Chile refused to salute Pareja's flag and war was declared. A squadron was formed with

of two Chilean ships and the Peruvian Navy. But Williams realized that little help could

be had from Peru and sailed out alone in the Esmeralda.

Since Pareja had no troops with which to attempt a landing he was effectively limited

to a blockade of the main Chilean ports. His squadron was reinforced with the arrival of

the modern ironclad Numancia, a powerful warship of forty guns. Even so,

the plan was Quixotic, for in order to blockade Chile's 43 ports and 1800 miles of

coastline, Pareja would have needed a fleet twenty times larger than what he had at his

disposal. The blockade of Valparaíso, however, caused great damage to Chileans and

neutrals. Pareja 's squadron captured some Chilean merchantmen, even some that had

switched to neutral flags. Still, the blockade was only partly successful. In Concepcíon

Bay a steam launch patrolling the inner bay was captured by the Chileans and placed under

their flag. Chile attempted to sell letters of marquee, but was unable to create a

privateer force as had been done in the War of Independence.

Rumors were spread in Europe however, and panic spread in Iberian waters. The Peruvian

ironclads, Huascar and Independencia, had sailed from

England and were said to be heading for Cadiz. In fact, the corvette Tornado

was captured off the Azores with a mixed European crew while on their way to deliver the

ship to Chile.

For two months nothing was heard of the Esmeralda. Williams was ready

to fight, even though his ship was in terrible condition: the hull leaked and the engine

needed a full overhaul. She could not steam at more than seven knots. He attempted to draw

some of the ships off Valparaíso, but the Spaniards would not chase him. Near Papudo he

came across the gunboat Covadonga. The Chilean approached under the

British flag, ready to board. No sooner was she in range, than the flag was hauled down

and a murderous fire discharged at the gunboat. The boarding party never had a chance to

fight because the Covadonga surrendered almost without a fight. With two

ships Williams set out to capture any Spanish ships that might come his way, but fog

prevented further operations; and when he contacted the government he was ordered to the

Chiloe archipelago to await the Peruvian squadron that was to join him there.

Pareja was unaware of the capture of the Covadonga. When the visiting

American consul casually mentioned it to him, the Admiral suffered a nervous collapse.

Next day after he seemed to have recovered, he dressed in his best uniform, lay down on

his bed, and shot himself in the head. Command of the squadron passed to the captain of

the Numancia, Commodore Casto Mendez Nuñez.

The Peruvian squadron finally joined up with the Chileans and came to anchor at Abtao,

a well protected inlet in the Chiloe channels. On February 7, 1866, the Spanish squadron

appeared at the entrance, but Mendez Nuñez was afraid to risk his ironclad in shallow

water. A cannonade lasting several hours was exchanged with very little effect. In spite

of being at anchor, without steam, and some ships even with their engines under overhaul,

the Peruvian ships fought with energy and determination. The Covadonga,

under the command of Lieutenant Manuel Thomson, managed to fire over an island and scored

several hits on the frigate Blanca. The battle ended indecisively without

further developments. Afraid of the shallow water and realizing that a long range gun duel

served no purpose but to waste ammunition, the Spanish commanders retreated. Williams and

the Esmeralda were not at the anchorage that day. The commodore had

sailed to Ancud for coaling.

A month later the frigates Numancia and Blanca

anchored at Tubildad, so close to the shore that a company of Chilean infantry approached

during the night, waited for roll call, and opened fire on the unprotected decks full of

men. Since the attackers were hiding among the rocks, the Spanish ships had to hoist

anchor and retreated without being able to answer the fusillade effectively.

Mendez Nuñez, like Pareja, failed in his efforts to conquer the Chileans or Peruvians.

The Spanish could not attack the land forces and they had been frustrated in engaging the

allied squadron at sea. The Spanish ships were isolated, short of supplies, and without

any hope of victory. The arrogant aggressors had turned into desperate men who needed a

spectacular feat to save their honor. In Spain, the government and the newspapers demanded

revenge. Mendez Nuñez determined on bombing Valparaíso and Callao.

The neutral British and American commanders, when notified of the intended plan of

attack, did everything short of direct intervention to avoid the destruction of a

defenseless port. It was even suggested that the two squadrons, less the Numancia

meet at sea to decide the issue. Commodore Rogers of the American squadron offered to

serve as referee. Mendez Nuñez liked the idea but could not take the responsibility; he

had been ordered to destroy the enemy squadron or a city and chose Valparaíso. Admiral

Denman of the British squadron also conferred with the Admiral to no avail. General Judson

Kirkpatrick, American minister to Chile, demanded that Rogers attack the Numancia,

but he refused to do so.

On March 31, 1866 the waterfront of Valparaíso was bombed and destroyed. For three

hours the Spanish squadron discharged its heavy guns against the city, destroying the

warehouses, the ancient unarmed fort, the railroad station, and other public buildings.

Fire fighting companies from Santiago assisted the local fire brigade in putting out the

fires and removing of debris. Damages to Valparaíso amounted to 14 million gold pesos, of

which six million belonged to neutrals, mostly British merchants.

Before leaving the coast of Chile, Mendez Nuñez set the captured Chilean ships afire.

All told, thirty-three vessels were burned or sunk. It was the total ruin of the Chilean

merchant marine. Twelve years later the total tonnage under the Chilean flag was still

less than half of what it had been in 1865.

To bomb Callao was no easy task. The city's forts and batteries were of legendary

power, had been kept on a war footing since Spanish times and were periodically

reinforced. When the Spanish squadron attacked on May 2, 1866, the forts returned the fire

and all the Spanish ships suffered damages and casualties. Nearly 100 sailors were killed

and Mendez Nuñez was wounded nine times. Two frigates had to be ran aground on San

Lorenzo Island. There the Spanish buried their dead, repaired their ships, and sailed off

into the Pacific. The war was over.

Technically speaking Chile had been responsible for the war. Without an adequate Navy

and no port fortifications, she went to the aid of a neighbor. The consequences were

serious: Chile's merchant marine was destroyed and the valuable warehouses of Valparaíso

were burned with all their merchandise. These setbacks to the Chilean economy would take

time to recover from. But at the same time the country had finally been made painfully

aware that Chile had to maintain a Navy to defend her coast. Two armored corvettes were

ordered in England and forts with powerful guns were erected at Valparaíso. A coast

artillery corps was created and auxiliary ships were also purchased.

Exploration and Colonization

Until 1843 the territories south of the Chiloe archipelago had not been populated

except for Indians. President Manuel Bulnes, elected President after his victorious

campaign against the Confederation, took the necessary steps to make Sarmiento de Gamboa's

dream finally come true. By ordering the establishment of a fort, he reinforced Chile's

sovereignty in the Straits of Magellan and Patagonia. Early in 1843, he ordered an

expedition to establish a colony in the shores of the channel. Captain Juan Williams, who

had taken the name "Guillermos," was placed in command of the 30 ton schooner Ancud.

The area south of the Straits had been charted earlier by Captain Robert FitzRoy of HMS

Beagle. FitzRoy returned to Chile in January 1834, bringing with him

three Yahgans who had been taken to England and also the naturalist Charles Darwin. For

more than a year the Beagle explored the southern channels collecting

specimens, charting the waters, and exploring adjacent lands. The Beagle

then proceeded north and explored the whole coast of Chile. Darwin's published findings

would make this trip one of the most memorable voyages of exploration in History.

After many difficulties Captain Guillermos entered the Straits on September 18, 1843,

Chile's national holiday. A few days later, after a short exploration along the coast, he

decided to establish the colony in the same place where Sarmiento de Gamboa had founded

the now extinct town of Rey Don Felipe at Port Famine.

The colony consisted of a small fort with a wooden stockade and four guns. It was not

meant to stop traffic in the Straits for the only defense planned was against possible

hostile Indians. It was named Fort Bulnes, in honor of the President.

From its origin the colony had to depend on the Navy for its existence. The brigs Condor

and Meteoro were used almost exclusively to supply the fort, but the

colony did not prosper. The weather was wet and cold, and nothing would grow. There was

not enough pasture and the whole area was surrounded by thick, impassable forests. In 1847

José Santos Mardones was appointed governor. He explored the surrounding countryside

carefully and decided that the very worst imaginable place had been selected for the

colony, so he decided to move his headquarters to the mouth of the Carbon river, today

known as RRo de las Minas, a place called Punta Arenas. The brig Condor

was used to move the colony and by 1849 Punta Arenas was firmly established.

Slowly but surely the Navy explored and later charted, the important ports along the

coast. In 1843 Roberto Simpson charted the mouth of the river Bueno. Later, a Navy

"commission", as they were called, charted Mocha Island, the rivers Maule,

Tolten, and Valdivia; and by 1862 a complete chart of the west side of Chiloe was

finished.

The revolution of 1851 served as an excuse for a murderous officer, Lieutenant José

Cambiaso, to foment a rising at the small colony at Punta Arenas in November of that year.

Claiming that he favored the revolutionaries, Cambiaso harangued the garrison, took over

the town, and imposed a reign of terror. He captured two merchant ships: shot their

captains and the Governor of Punta Arenas, Commander Benjamin Muñoz Gamero; he burned the

wooden buildings of the town and finally escaped into the Atlantic with whatever money he

had stolen. But near the Falkland Islands, his crew took him prisoner and returned him to

Valparaíso where he was executed. The Navy had been unable to help: the two ships were on

the north coast of Chile and there were no other naval forces to quell the mutiny.

The Navy also served the small colony at Juan Fernández Island and eventually took

possession of the small islands of San Felix and San Ambrosio.

By 1870 the exploration activity took on a new and intense importance. The Navy started

systematic mapping of the southern archipelago. The corvette Chacabuco, a

brand new ship built in England, charted the Guaitecas Islands and other ships not only

explored and charted the Magellanic channels but even went up the Atlantic Coast of

Patagonia to the River Santa Cruz. In command of all explorations was Captain Enrique

Simpson. Lieutenant Francisco Vidal Gormaz , who would eventually become the most

brilliant of Chile's hydrographers and surveyors, started his career under him.

The Argentinians had not yet taken possession of the Atlantic coast of Patagonia, but

because of Chilean advances a new policy was determined by Buenos Aires aimed at putting a

stop at Chile's exploration and starting its own expansion into Patagonia. A tense climate

was created and of course the colony at Punta Arenas was at the center of the storm.

Since 1874 Punta Arenas had been governed by an Army Captain, Diego Duble Almeyda, a

veteran of the California Gold Rush. Duble had given great impetus to the region's

progress. He had brought sheep from the Falklands and under his protection several

European pioneers had established themselves in the town. Among them were Elias Braun,

José Menendez, and José Nogueira, all of whom would in time represent the three largest

fortunes in the area. Unfortunately the colony was also used as a penal establishment and

because of its isolation the soldiers of the garrison soon saw themselves also as if they

were in prison. The actual prisoners enjoyed almost complete liberty during the day while

some of the soldiers had to serve long hours at guard duty. On November 11, 1877 the

artillery company mutinied and took control of the town. Duble showed great bravery and

tried to stop the insurrection by himself. He was hit on the head by a rifle butt and a

caisson rolled over his leg. In the drunken orgy of that first night, he was given up for

dead. But next morning, wounded and limping, he walked through the hills towards the Percy

river, where he knew a Chilean gunboat was charting the waters. After swimming across a

river and two days without food, sleep or, shelter, Duble reached his destination. Captain

Juan José Latorre of the gunboat Magallanes immediately moved on Punta

Arenas but the mutineers had left after burning and sacking the town. Some were

apprehended, but others escaped into Argentina which refused to extradite them. Nine of

the prisoners ultimately were condemned to death by a court martial and executed in the

main square of Punta Arenas.

The result of the mutiny was the elimination of the penal colony and the establishment

of better living conditions and regular rotation of the garrison. The city prospered with

the production of wool in the area and the constant traffic of steamers which now

transited the Straits.

The Navy also participated, peacefully but actively, in the Chilean expansion into the

northern desert of the Atacama. There was always a need to keep a ship stationed on the

Bolivian coast, to aid navigators, explore the coast, assist the local population when

earthquakes struck, and, on occasions, to stand firm against Bolivians authorities when

they attempted to infringe on the rights of Chileans mining in the area.

During this period of Chilean expansion, the Chilean Navy took a most active part in

the colonization and exploration of new territories. An equal zeal would soon be displayed

at war.

The War of the Pacific: Iquique

In 1871 Federico Errazuriz was elected President of Chile. Errazuriz had served as

Minister of War during the Spanish War. He resisted all efforts to disarm Chile. When

faced with complaints that the Army was useless and that it could be replaced by an

irregular militia such as the National Guard, he refused to yield. The Chilean Army had a

esprit de corps and an image based on literature myths and historical facts that went

as far back as Lautaro and Valdivia, and was reinforced during the War of Independence by

the heroic deeds of O'Higgins, Rodriguez, and Carrera. The Army had been trained in

frontier war and molded into a disciplined and loyal force under the leadership of

Portales' generals. Errazuriz provided it with the most modern weapons available. The

President was keenly aware of Chile's vulnerability from sea attack. He not only accepted

the purchase of two ironclad corvettes, the Chacabuco and O'Higgins,

but he insisted on purchasing two ironclads of the most advanced design. Powerful, heavily

armed, and thickly armored, the Cochrane and Blanco Encalada

were ships that would soon revolutionize naval warfare. Admiral José A. Goñi travelled

to England and insisted that the design provide heavy armament, thick armored plates, and

powerful engines. At the same time several auxiliary craft were added to the Navy. The

defenses of Valparaíso were reinforced and garrisoned by a strong, well trained group of

artillery men who could double as marines. But by far Errazuriz's greatest contribution to

national defense was sending Army and Navy officers to Europe where they gained knowledge

and experience that no other Latin American officers had. Thanks to him, the Chilean Navy

was not larger but at least equal to, and better trained, than the squadrons of

neighboring countries. When an economic crisis required the country to go on an austerity

program, the President insisted that the defense budget not be touched and dismissed

outright suggestions that he sell the ironclads.

His successor President Anibal Pinto inherited the growing problems of Chile's

expansion. The most serious was the southern tip where Argentina disputed Chile's claims

to the Straits, Tierra del Fuego, and Patagonia. Except for the small colony at Punta

Arenas, the immense region was inhabited by Indians whose quality of life was so wretched

and whose conditions so miserable that nobody had thought of civilizing them. The only

contacts with them were belligerent. Unfortunately for Chile opinions were divided and

those who thought Patagonia worthless were in charge of negotiations. Chile offered to

give up its claim to the Eastern Coast of Patagonia and settle the boundary South of

Gallegos river. Neither concession satisfied the Argentinians. When the gunboat Magallanes

captured the American bark Devonshire, which was loading guano in

disputed waters but with Argentinian permission, the public outcry in Buenos Aires could

not be contained. The government responded by sending a squadron to the Santa Cruz river.

Pinto ordered the Navy to man its squadron and to get ready for war. Chilean ships

concentrated in Lota where the shops of the coal mines could repair and overhaul the

ships.

Both countries realized that a war would be costly and the Chilean concessions were

accepted in a Treaty signed and ratified in the early days of 1879: Chile retained control

of the Straits, the borders with Argentina were settled, and Chilean expansion in

Patagonia was checked.

While the squadron was still at Lota, a new conflict with Bolivia arose over the

latter's increase of taxes on the production of nitrates in open violation of an existing

treaty. The Chilean mining companies in Bolivian territory refused to pay more tax. The

Bolivian government ordered the seizure of the properties and their sale at public

auction. Pinto ordered the immediate occupation of the Bolivian port of Antofagasta. The

operation was executed by the ironclads Cochrane, Blanco, and the

corvette O'Higgins.

The government of Peru made a feeble attempt to negotiate the dispute while

simultaneously preparing for war. Peru had already signed a secret treaty of alliance with

Bolivia and Pinto felt the negotiator was acting in bad faith. On April 5, 1879 Chile

declared war on Peru.

The barren deserts, without water, roads, or centers of population, made it necessary

that the belligerent countries struggle for control of the sea. Peru had a fair Navy built

around two ironclads, the turret monitor, Huascar, with two 300 pound

Dalhgren guns and six inches of armor protection , and the steam frigate Independencia

with five inches of armour plate and smaller guns. Peru also had two wooden but fast

corvettes, the Pilcomayo and the Union , and two shallow

water monitors, the Atahualpa and the Manco Capac, which

had previously belonged to the United States as the Catawa and Oneonta.

All four ironclads were armed with powerful rams.

Chile had the two sister ships Blanco Encalada and Cochrane,

each armed with six 9-inch Armstrong guns and protected by a 9 inch armor belt. In

addition to the two ironclad corvettes from which the iron plates had been removed, Chile

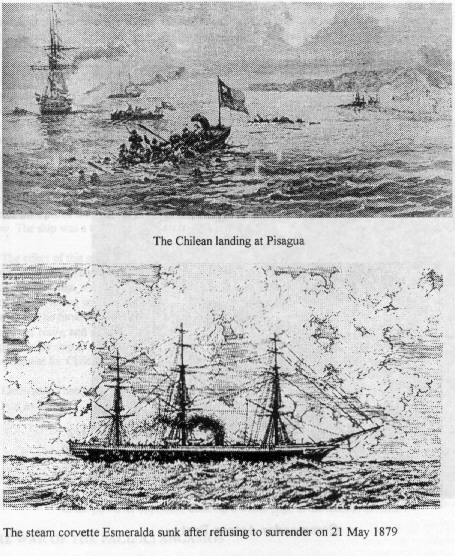

had two older ships, the corvettes Esmeralda and Abtao.

They were both in bad shape. The Abtao had been sold into private hands

just before the war and it was necessary to cancel the sale. The Esmeralda

leaked badly, was armed with obsolete guns, and had an almost inoperative engine. The

sloops Magallanes and Covadonga were too smaller ships

but at least in good running conditions. But while the Chilean officers and men had been

trained in British methods and maintained a tradition of excellence which made them an

efficient fighting force, the Peruvian Navy was poorly trained, poorly paid, and the best

sailors were foreign. In fact, upon the declaration of war many Chileans who were serving

in Peruvian ironclads went directly into the Chilean Navy.

Bolivia had no Navy and her Army, poorly armed, consisted of Indians shod in sandals

and with improper uniforms. Still, accustomed to long journeys and heavy loads, they

possessed endurance and determination that would have made them effective warriors had

they been properly trained, led and equipped.

The Chilean government had fostered a strong Navy because it was fully aware that sea

power was of vital importance to the nation's defense. Once hostilities were imminent,

Chile showed her intention to carry out all naval operations by steam alone. All upper

spars, top masts, and non-essential rigging were sent ashore to be used as derricks. The

crews were increased to full complements and all retired officers were recalled to active

duty.

February 14, 1879, the very day on which the auction of the nitrate companies was to

take place, Colonel Emilio Sotomayor landed at Antofagasta at the head of 500 men. He met

no resistance and was able to advance into the interior and secure his position.

The Navy was under the command of Rear Admiral Juan Williams, the man who had

distinguished himself in the previous War with Spain and son of Juan Guillermos. Williams

ordered the occupation of Cobija and Tocopilla so that by April 5th, when the war between

Peru and Chile was declared, all of the coastal territory of Bolivia was under Chilean

control. He set out to blockade Iquique, the main Peruvian port in the area and the center

of Peruvian nitrate shipping. His squadron proceeded systematically to destroy all loading

lighters, launches, piers and docks in the southern ports of Peru. Attacks were carried on

as far north as Mollendo which was bombarded on April 17th. The next day the Blanco

and O'Higgins bombarded Pisagua.

The Chilean Army concentrated at Antofagasta and all supplies and troops had to be

brought therefrom central Chile by sea. Shipping merchants who provided transports were in

constant danger from raiding Peruvian warships. Little consideration was given to their

safety, even after a daring ambush attempt on April 12th. Commander Juan José Latorre in

the Magallanes was carrying dispatches when he found the Peruvian

corvettes Union and Pilcomayo waiting for him near Punta

Chipana at the mouth of the River Loa. Latorre could have turned and fled south, he chose

instead to force his way through. His armament was far inferior to that of his attackers

but by increasing his speed he fought with only one enemy ship at a time. Both Peruvian

ships were hit and the Union had to retire to Callao for repairs. Latorre

arrived at Antofagasta without mishap or even delay, but without his dispatches. He was so

unsure of the outcome of the encounter that he had thrown them overboard to avoid capture

by the enemy.

President Prado of Peru decided to take command of the war at the very center of the

theater of operations. He left Callao in the Huascar, in convoy with the Independencia

and the transports Limeña and Chalaco. At the same

time, Williams had decided to attack Callao with his squadron. The two convoys passed

without sighting each other. On May 21st, Williams found Callao empty and rather than take

his chances with the shore batteries, he ordered a return to Iquique.

Two Chilean ships had been left to blockade Iquique. They were, with the possible

exception of the Abtao, the two worst hulks afloat: the old corvette Esmeralda

and the smaller Covadonga. The senior officer was Commander Arturo Prat

Chacon of the Esmeralda. There is no doubt that the two ships had been

left behind because of their slow speed and their poor condition. On the other hand, Prat

and his officers were probably the best junior officers in the Navy, as their subsequent

action actions clearly indicated.

Prado arrived off Arica and landed the troops. He was informed that two weak ships had

been left in charge of the blockade of Iquique. He called Captain Miiguel Grau of the Huascar

and entrusted him with the seemingly easy mission of capturing the Chilean ships and

lifting the blockade. Grau was then ordered to proceed to Antofagasta and bombard the town

and Chilean Army headquarters there. Grau was a capable, responsible, and cautious man.

Knowing full well that his two ironclads were Peru's only hope, he made sure, by stopping

at Pisagua and checking by telegraph, that the main Chilean squadron had not yet returned

to Iquique.

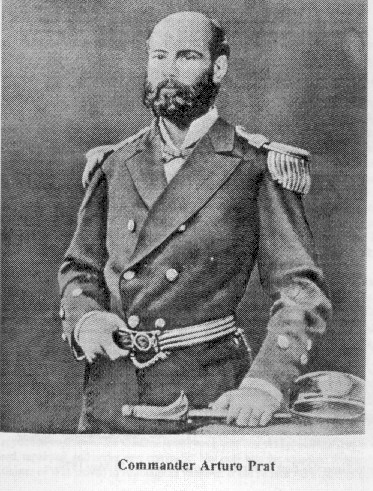

Commander Arturo Prat was a serious and dedicated man. He was born in the Central

Valley south of Santiago; he had entered the Naval Academy at Valparaíso and followed a

career marked by devotion to duty; he had participated during the War with Spain in the

combats at Papudo and Abtao and was well liked by his officers and men; he had managed to

study law , passed the bar and even taught night school. Williams is said to have disliked

him because he was a "literary mariner". Nevertheless, the Admiral did choose

him to command the blockade. He was 33 years old.

In the early morning hours of May, 21st, the two Peruvian ironclads approached Iquique.

The Covadonga , under command of Lieutenant Commander Carlos Condell, was

patrolling outside the bay and on sighting the enemy fired a warning gun and approached

the Esmeralda. The Captains addressed each other through speaking

trumpets. Prat ordered Condell to follow him and to take a position in the shallows in

front of the town. He hoped to force the Peruvians to fire into their own countrymen

ashore. As they were moving into position the first shot was fired by the Peruvians and

Condell realized that he could escape by rounding the island at the mouth of the bay. He

decided to try it, a decision which was reinforced by the fact that several launches with

Peruvian soldiers were seen preparing to set out from the beach; the small Covadonga

could easily have been boarded while under attack by the ironclads. The Independencia

under the command of Captain Moore, set out in pursuit of Condell.

Prat rallied his men. At no time did he think of surrendering; he was ready to give up

his life. He could not escape on account of the slow speed of his ship, neither was his

armament any match for the enemy's iron plates. Still, he cleared his ship for action,

ordered the men on deck, and told them in plain words what he expected to do:

"My boys, the odds are against us; our flag has never been lowered in front of the

enemy; I hope it will not be today. As long as live that flag shall fly in its place and

if I die, my officers will know how to do their duty. Viva Chile!" (6)

The crew responded with a cheer and took their battle stations. The Huascar

placed itself at a comfortable distance and proceeded to discharge its heavy turret guns

towards the Esmeralda. She remained motionless but active; from her tops,

rigging, and decks a steady rifle fire was maintained. So strong was the fusillade that

Captain Grau thought it was coming from machine guns. Nonetheless, the Esmeralda's

obsolete guns could only cause minor damage to the ironclad. After three hours of this

duel, the Esmeralda was barely damaged because of the inaccuracy of the

Peruvian gunners and the odd angle at which they had to fire to avoid the town. Meanwhile

the Peruvians on shore brought a field piece to the beach and this gun inflicted serious

damage to the corvette. Prat could not maintain this position any longer and decided to

move. During this critical maneuver one of the four boilers burst, leaving him with almost

no power. Until that time Captain Grau had not attempted to ram his enemy for fear that

the Esmeralda was at anchor protected by mines or torpedoes. But now it

was clear that she had no protection and Grau ordered a ram at full speed. Prat saw him

coming and almost avoided the collision in spite of his low power. The Huascar

struck at an angle and the impact carried her alongside the Esmeralda

toward her stern. Captain Prat climbed over the railing and jumped on board the monitor

calling on to his men to follow. Only marine Sergeant Juan Aldea was able to do so. As the

Huascar retreated, one more sailor jumped on board her. The three were killed almost

immediately on board the Huascar, though Captain Prat succeeded in

advancing towards the turret and killed Lieutenant Valverde before being shot himself.

Command of the Esmeralda fell to Lieutenant Luis Uribe. Everybody on

decks and rigging of the Esmeralda had seen their captain die. Now, more

than ever, they resolved to fight to the death. If they could not avenge Prat they would

follow his example. Another ramming afforded Lieutenant Ignacio Serrano the opportunity to

try a second boarding. This he accomplished but Serrano and his twelve men were almost

quickly overcome and killed on the deck of the Huascar. The Peruvians

kept firing their guns before and after the collision, so that the carnage on board the Esmeralda

was appalling. By the second ramming, half the men had been killed. The magazine, the

boilers, and the lower compartments were under water. The rigging was shot away and the

guns dismounted. She would not surrender and whoever could still discharged his pistol or

rifle towards the enemy. When the Huascar rammed for a third time nobody

was left to board her. Seconds later Esmeralda sank as Midshipman Ernesto

Riquelme fired the last round from the last gun afloat. Down went 150 of her 200 men crew.

Lieutenant Uribe was later rescued. He and his men were imprisoned in Iquique. The

fight had lasted four hours. Damage to the Huascar was considerable, but

not serious: as a result of the ramming her forward compartment was flooded and the turret

was out of alignment.

While Prat's ship was unable to move, the Covadonga was making good

progress south, followed closely by the Peruvian ironclad. Condell, like Prat, ordered his

men up into the riggings. From there, they succeeded in preventing the enemy from manning

the Independencia's bow guns. Condell maneuvered close to land and

successfully evaded two attempts to ram. Off Punta Gruesa his ship touched bottom.

Realizing his tremendous advantage he presented his broadside to the enemy. Moore charged

to ram only to strike the reef at full speed. The Independencia keeled

over, her bottoms ripped open, her back broken, and her guns dangling at impractical

angles. Condell ordered his ship to turn around, and placing himself in the dead angle of

the enemy's armament , proceeded to rake her deck until her flag was struck. At about that

time the Huascar was sighted and Condell, realizing that everything was

lost at Iquique, escaped at full speed. He left behind the smoldering wreck of what had

been Peru's proud ironclad. Grau attempted to salvage the frigate, but all he could do was

rescue the crew. The ship was a total loss.

The effect of this gallant behavior at Iquique was electrifying. Few times in History

has the conduct of one man so profoundly affected a nation. There had been some resistance

to the war until that time but Prat, a modest, unknown officer, who had given all he had

in defense of his country, awakened the dormant patriotism in every Chilean. From that

moment on, everyone rallied to his example. Young men had to be turned back from Army

barracks, children ran away from school to join the ranks of the Army and Navy, and

donations for the purchase of a new Esmeralda soon amounted to enough

cash to pay for the ship in cash. For all practical purposes, Prat had lost his ship and

possibly the battle, but won the war for Chile.

Lieutenant Theodore B. Mason, writing for the U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence

commented on Prat as follows:

Was this young senior officer fitted by his antecedents to surrender? The answer to

this questions is his conduct in the engagement that was about to take place-- a fight

that astonished the naval world; which established the precedent that, no matter what the

odds be, vessels must be fought to the last, and which on account of the intelligence and

intrepidity that characterized it, and on account of the harm that was actually done to

the powerful opponent, deserves a whole page in the records of fame.(7)

The War of the Pacifics: Angamos

Although Chile was swept by patriotism and enthusiasm, the squadron's morale sank when

the crews and officers learned the news of Iquique. In spite of Prat's brave actions, the

fact that he and 150 of his men had been killed because they had been left behind caused

much displeasure among the officers and men. Williams had to accept full blame for his

ill-conceived plan to attack Callao and returned to the blockade of Iquique. En route he

encountered the Huascar on the high seas, but was unable to get close

enough to engage. The monitor succeeded in reaching Callao where it went into the shipyard

for repairs. After destroying the Esmeralda and chasing away the Covadonga,

she had twice engaged the shore batteries at Antofagasta with little success.

Grau set out to disturb Chilean communications as much as possible. With the Huascar's

high speed and freedom to maneuver he became the scourge of the Chilean Navy. Entering

Chilean ports he would destroy launches, pontoons, piers, and captured several small

sailing vessels. Grau always managed to get away before the Chilean ironclads could close

in.

On the night of July 10th, the Huascar entered Iquique and attempted

to capture the collier Matias CousiZo. Before Grau could take possession,

the Magallanes with Latorre in command appeared out of the darkness and

engaged in close fire. Four times Grau turned his ship to ram, but Latorre managed to

evade by using the rudder and the twin screws of the gunboat. The Chileans kept a regular

fusillade of small arms fire and even managed to hit the Huascar with a

115 pound shot. But all these impacts had little effect. The Magallanes

had not ben hit when the Cochrane finally appeared attracted by the

explosions and by numerous rockets that Latorre had fired. Grau had strict orders from

President Prado not to engage the ironclads and fled into the darkness. Latorre whose name

was already a household word because of his gallant behavior at Chipana on April 12th, was

lauded by the press. Public outcry over the effectiveness of the Navy demanded an ironclad

for Latorre. He would eventually take over the Cochrane.

On July 23rd the Huascar, in company with the Union,

captured the Chilean transport Rimac off Antofagasta. This ship was

carrying a cavalry regiment with 300 horses. Grau was at the height of his glory. The

horses were turned over to the Peruvian army, the prisoners were landed at Arica, and the

transport was armed and commissioned as a Peruvian cruiser.

Public outrage in Santiago rose to unexpected violence. The Minister of War, Gregorio

Urrutia, was stoned as he left Congress. The parliament bitterly attacked him and demanded

changes. Pinto reacted by appointing Rafael Sotomayor, a civilian, as Minister of War.

Sotomayor ordered Admiral Williams to lift the blockade of Iquique and brought the

ironclads, one at a time, to Valparaíso to have their hulls cleaned by divers and their

machinery overhauled. It was felt that Williams lacked the skill to command the squadron

and he was relieved. Captain Galvarino Riveros was put in command. Latorre was appointed

captain of the Cochrane and soon she was ready, like the rest of the

ships, rearmed, repaired, repainted, and under new command. Not only was the squadron

thoroughly reorganized, but the Minister of War moved to Antofagasta where he could be

near the theater of operations.

The object of all these preparations was to capture or sink the Huascar.

But for a while at least Grau succeeded in preventing the Chilean commanders from

achieving their offensive campaign. On August 27th she entered of Antofagasta and engaged

the Magallanes and Abtao at long range. That night she

launched a Lay torpedo at the Abtao, but the wires became tangled and the

torpedo turned back toward the Huascar. The Peruvians claimed that

Lieutenant Diez Canseco jumped overboard and deflected the torpedo. But Grau, who usually

praised his men when they deserved it, wrote a short battle report saying:"one of the

torpedoes was launched but so unsuccessfully that, that we had to lower one of the boats

to pick it up."(8)

He continues to say that he spent the rest of the night searching for it. If Lieutenant

Canseco did perform this heroic deed, his commanding officer certainly did not mention it.

During this action the Huascar was hit by a 300 pound shell that

caused considerable damage on deck, killing one officer and wounding several men.

By October 1st, Riveros was ready. He received explicit orders from the Minister of

War: attack and destroy-- sink or capture the Huascar no matter where she

is found.The task was an extremely difficult one but Riveros proceeded methodically and

diligently and his efficiency paid off. He sailed north to Arica and from some fishermen

whom he met at sea he learned that the Huascar had gone south. He was

determined that this time Grau would not escape. Riveros decided to cover as wide a range

as possible. For this he divided his squadron into two divisions.

The first was placed under Latorre with the Cochrane and the fastest

ships. Riveros retained the Blanco and the rest of the ships. Latorre was

to cruise 20 or 30 miles off the coast, while Riveros would cruise 50 miles ahead and

close to the shore inspecting all ports, bays, and inlets where Huascar

might hide.

In the early morning hours of October 8th the Huascar and Union

were steaming north. Lookouts sighted columns of smoke on the horizon and

awakened Grau. The commanding officer, now promoted to Rear-Admiral, ordered a change of

course to the west and trusted his superior speed to do the rest. So confident was he that

he went back to sleep. The monitor was gaining on his pursuers when at 7:30 AM three more

columns of smoke were sighted dead ahead. Grau was called again to the bridge and he must

have realized that he was trapped. He ordered the Union to run north at

full speed and rather than take further evasive maneuvers to the west he attempted to

escape by passing between the Cochrane and the coast.

The Cochrane could now make close to eleven knots and under the

command of Latorre, who had shown his skill before, the crew was in prime condition for a

fight. In less than two hours the ships were within range. Latorre did not want to lose

speed by veering off to fire a salvo so he kept his guns silent until he could be sure

that the Huascar could not escape.

At 9:25 AM Huascar opened fire. Her shots fell short but the fourth

attempt ricocheted and, passing through the bow plates, struck the Cochrane's galley.

Latorre relentlessly continued and when he was barely 600 yards away from the Huascar

he opened fire with devastating effect. Hardly a shot was missed. On the first salvo the Huascar

was pierced under the tower. Her steering gear was put out of commission; and in the

following salvos a shell struck the conning tower and exploded inside, killing Admiral

Grau. The Huascar was still dangerous: one of her 300 pound guns was

still firing and her powerful ram was an extreme menace. In fact, both ships attempted to

ram each other, but neither could do so. The Chileans kept up a brisk fusillade with

rifles and two machineguns in the tops, which required the decks of the Huascar

to be evacuated.

By 10:00 AM, after half an hour of combat, the ironclad Blanco Encalada reached

the scene, coming at such high speed and her crew so eager to join the fight, that she

almost ran into the Cochrane. Latorre had to maneuver to get out of the

way of his own Commodore. Under fire from the two ironclads and other smaller ships,

including the Covadonga, Huascar was almost disabled.

When her flag was shot away it was thought she had surrendered, but she kept fighting and

raised a new flag. By 11:00 AM she could not carry on and surrendered. A fire was started

and her sea cocks were opened. But Latorre was prepared for this eventuality and two fast

boats from the Cochrane under the command of Lieutenants Juan T. Rogers

and Juan Enrique Simpson were sent over. Pistols in hand, they forced the crew to flood

the magazine and put out the fire. The sea cocks were shut just in time.

Few ships in history have sustained such terrible damage and still remained afloat. The

Chilean armament had been devastating and the accuracy superb. Nearly fifty per cent of

the shots had found the target. The scene on board the Huascar was

dreadful. Dead and wounded were lying everywhere; one third of the crew was dead or

wounded. The weak armor of the Huascar had been worse than useless

because the Chilean shots easily penetrated and exploded inside and sent thousands of

pieces of shrapnel everywhere.

The rams were equally unavailing. Only armament had brought the fight to an end. The

Peruvians had shown great valor fighting against such odds but they had lost the Huascar

and with her their last hope of controlling the sea. Now the Chileans could carry out

their plans ashore, attacking, landing, and supplying troops at will.

The Huascar was taken to Valparaíso after some hasty repairs. A few

guns were added and the ship joined the Chilean squadron under the command of Manuel

Thomson. The Union had successfully escaped Angamos, easily outrunning

the Chilean corvettes which had abandoned the Cochrane to pursue her.

The Navy and the Invasion of Peru

With the sea under their control, the Chilean could now move on shore. Sotomayor now

executed his plan to capture the nitrate rich province of Tarapacá. On the morning of

November 2,1879 a Chilean fleet composed of six warships and ten steamers appeared befor

CHAPTER III

O'Higgins managed, by shifting all but one gun to the opposite side, to bring

the gun to bear on enemy trenches. It was a bloody fight, every inch of the way with loss

of nearly half the attackers. In two hours the bluff had been cleared and the railroad

stock-- cars, engines, and all gear-- captured. The force scheduled to land at Junin could

not be landed in time because of high seas and therefore played no part in the battle.

The Chilean Army, 7000 strong, moved inland and took up positions at San Francisco.

There it was attacked by combined Peruvian Bolivian forces which the Chileans routed.

Although the Peruvians achieved a small victory at the town of Tarapacá, the allies

evacuated Iquique and gave up the whole province to the Chileans.

With the province of Tarapacá in Chilean hands, the squadron established a blockade of

the Peruvian coast from Arica to Mollendo. Riveros, cruising with the Blanco

Encalada alone, encountered the Peruvian corvette Pilcomayo

which was abandoned and set afire by her crew upon sighting the ironclad. Chilean sailors

boarded the ship, put out fires, and hoisted their flag. Peru's effective Naval power had

been reduced to just the Union and her coast defense monitors.

The next step for the Chileans was to capture Arica. Twenty transports were

concentrated in Pisagua and on February 24th, 1880 they appeared off Pacocha, a small town

north of Arica where the Army of 12000 men was landed without opposition. At the head of

the Chilean land forces rode a new commander, General Manuel Baquedano. Baquedano pushed

his Army into the desert, attacked and dislodged the Peruvians entrenched at Los Angeles

hills, and then defeated the combined Peruvian and Bolivian Armies at Tacna.

Riveros in the meantime, kept steady pressure on Arica from the sea. On February

27,1880, the Huascar and Magallanes entered the bay and

fired on a troop train that was ready to leave. Arica is protected by a huge rock: the

Morro. From this high rising bluff just south of the city, Peruvian artillery opened up on

them. Although struck by a shell the Huascar retreated only temporarily

from the line of fire and when Captain Manuel Thomson again guided her closer to the

enemy, the monitor was hit several times as she engaged not only the forts but also the

ironclad Manco Capac. When the Manco moved to close the

range, Thomson attempted a daring maneuver: circle around his enemy and take her former

position under the Morro thus preventing the Manco from returning to her

anchorage. But at a critical moment her engine failed and Huascar became

an easy target for the 200 pound Rodman guns mounted on the Manco. A

well-aimed shot landed on deck and exploded; Captain Thomson was instantly killed, his

head and sword being left on deck. Commander Valverde, second in command, needlessly

exposed the ship to one more hour of heavy gun fire before finally retreating. That

evening Captain Condell took command of the Huascar.

The Chileans kept up a tight blockade but captain Villavicencio of the Union

managed to land a valuable cargo of supplies for the besieged Army. Just as the Chileans

were planning to attack on the Union, Captain Villavicencio brilliantly

escaped in broad daylight, running his ship towards the south and confusing the blockading

squadron. The Union's tremendous speed had saved her once more from

Chilean guns.

After the crushing defeat at Tacna, the Bolivians abandoned the fight and did not

actively participate in the war. The remnants of the Peruvian Army retreated to Arica but

the town was evacuated and all defenses concentrated on the Morro. On June l6th the

Chileans launched a combined sea and land attack against the bastion. Peruvian artillery

silenced the Chilean field guns and opened a devastating fire on the ships within range.

The Magallanes and Covadonga were hit. One shot entered

the gunport of the Cochrane's second starboard gun, exploding the shell

that was being loaded and an additional charge that was being readied in the compartment.

A series of explosions followed and twenty-seven men were wounded. The Cochrane

was seen retreating in a cloud of black smoke but the damage was not serious.

The next morning a Chilean infantry column assaulted the fortress and succeeded in

reaching the top of the rock after a bloody bayonet charge. Colonel Bolognesi in command,

and Captain Moore of the ill-fated Independencia were killed in the

fight. The Manco Capac was scuttled and her crew surrendered to the

nearest Chilean ship. A torpedo boat that attempted to escape was driven into the breakers

and destroyed by the tender Toro.

The conquest of Arica marked the end of the Chilean expansion campaign. It was now

thought that peace could be negotiated. Baquedano, with this in mind, ordered his Army

quartered at Arica for the winter. Chile accepted a mediation offer from the United States

and representatives of the three nations met on board the U.S.S. Lackawanna.

But Chilean conditions were not acceptable to either Peru or Bolivia and when it became

clear that the Peruvians were not yet convinced of their defeat, it was decided to carry

the war to the capital of Peru, Lima.

After the capture of Arica, Riveros agreed to allow the transport Limeña

to carry wounded and sick Peruvian soldiers to Lima. Since there were more troops that the

Limeña could carry, some of them were placed on board the Chilean

warship Loa and safely delivered to the hospitals of Lima and Callao. On

July 3, 1880 the Loa came upon a small coasting vessel loaded with fresh

provisions. As the last crate was being removed, a terrific explosion blew a large hole on

the side of the Loa, and the ship sank almost immediately with great loss

of life. Less than two months later, a similar fate befell the historic Covadonga

at Chancay. Only fifteen men succeeded in escaping. Although it was obvious that the

Peruvians could not possibly have selected the two ships to be sunk, the Chileans were

angered by what they considered cruel and inhuman acts of war. The Loa had

just returned from a humanitarian mission in Peru's interest; and sabotage to the Covadonga

was an insult and outrage to Chile as well, for the ship had been captured during the War

with Spain that Chile had entered in defense of Peru. Public pressure demanded that

Riveros put an end to the torpedo menace and he retaliated as strongly as he could. First

he demanded that the Union and Rimac surrender; when the

Peruvians refused as expected, he ordered the bombardment of Chorrillos, Chancay, and

Ancon.

That same month Captain Patricio Lynch was sent with a 3000 man force to attack the

northern coast of Peru. The purpose of this expedition was to inflict as much damage as

possible on the northern ports and thus to discourage their inhabitants from supporting

the war in the south. The Chileans destroyed government and private property in all ports

between Callao and Payta and in some cases they even ventured inland. Lynch demanded

payments from local authorities and large property owners. When they refused to comply

their property was destroyed. Although large amounts of money and supplies were gathered,

great damage was caused by this expedition. Lynch had been scrupulously honest in keeping

close accounts of his collections and everything was turned over to the government, but

foreign countries looked upon the expedition as a piratical cruise, specially since many

neutrals were involved in paying ransoms and others lost their properties. Indeed, Lynch's

activities created almost insurmountable diplomatic difficulties for Chile.

A blockade of Callao was maintained in spite of repeated efforts by the Peruvians to

torpedo the Chilean squadron. Several types of mines and five types of torpedoes were

used, including some launched by a submarine, El Toro Submarino, which

had been successfully tested in twelve dives. More frequent and practical, were the

torpedo boats. Every night patrols from both countries cruised the bay and encounters were

frequent. Every conceivable trick was used to bring the Chilean torpedo boats within the

range of the shore batteries.

On December 6, 1880, a small Peruvian convoy was seen moving from the inner harbor.

Three Chilean torpedo boats, Fresia, Guacolda and Tucapel,

went to meet it at full speed. The convoy was merely a bait, a steamer with a heavy armed

barge under tow followed. Shore batteries opened up and the Chilean squadron promptly

responded but the Fresia was hit and sank in 15 fathoms of water. Chilean

divers raised her from the bottom and in a matter of days she rejoined the blockading

forces.

The Chileans needed longer range guns to engage both the batteries and the ships close

in shore. A former Irish "pig boat", re-named Angamos, was

armed with an 8-inch, 180 pounder, breech loading Armstrong and converted for naval use.

Every day at sunset the Angamos would steam up to the limit of the range

of the shore batteries and open fire on the fortifications and anchored ships from a

distance of 8000 yards. But in late December of 1880, during an attack, the gun recoiled

so violently that the barrel disconnected from the carriage, bounced on deck, killed two

people and fell overboard.

The Peruvians were unsuccessful in scoring any hits at Callao. The preventive measures

taken by the Chileans were strictly observed. The squadron sailed out to sea at night and

returned cautiously next morning. The blockade was maintained at night by the torpedo

boats which prevented any vessels from entering or leaving the harbor.

The blockade was not lifted even to convoy the transports bringing the Army from Arica.

This Army consisted of three divisions with a total strength of 26,000 men under the

overall command of Baquedano. It was transported on board 36 ships.

On November 18, 1880 the first division landed at Pisco and proceeded on foot up the

coast protected by warships which followed the troops' slow progress on land. Baquedano

was dissatisfied with the slow pace. He removed the commanding officer and appointed

Captain Lynch of the Navy to take command of the First Army Division. His prestige was

such that many high ranking officers who might have been expected to take command,

welcomed him. A week later, the Second Division landed at Chilca and occupied the town of

Lurín, while the Third Division landed at Curayaco and occupied the ancient city of

Pachacamac. All three landings were unopposed. Baquedano dispersed some of his regiments

to offer some security on the flanks and front, and established his headquarters at

Lurín.

The first attack on Lima took place against the fortified line of Chorrillos in the

early morning hours of January 13, 1881. As soon as daylight broke, the Chilean squadron

opened fire on the Peruvian position around Morro Solar a rocky mountain facing the sea,

forcing the Peruvians there to retreat towards Chorrillos where they came under attack of

Lynch's First Division. By 2:00 PM the Chileans had occupied Chorrillos.

An armistice was arranged by the Lima diplomatic corps but on January 13, while

Baquedano was reconnoitering the lines in front of Miraflores, the Peruvian naval brigade,

a group formed by the crews of the ships in Callao, opened fire on the escort. A cease

fire was attempted but when it proved impossible, forces on both sides of the line engaged

in battle. The ships started an intensive cannonade which, though tactically useless, was

encouraging to the Chilean infantry. By sundown the battle of Miraflores had been won by

the Chileans at a cost of over 2,000 casualties. The Peruvians claimed 2,000 dead on their

side, a figure not our of proportion when one considers that the Peruvian Army ceased to

exist after the two battles.

Baquedano ordered his Army to camp outside Lima and that night a mob, led by stragglers

from the Peruvian Army, sacked Lima and Callao. A group of foreigners formed a civil guard

and restored an uneasy peace until the Chilean Army occupied the port and the capital. The

Peruvians officers ordered all ships blown up to prevent capture by the Chileans. The Union,

Atahualpa, and Rimac were destroyed. The forts were blown up and

the remaining troops disbanded. When Lynch arrived to take over as military governor of

Callao he was greeted by smoking ruins and half submerged wrecks.

Although it would be years before the hostilities ceased entirely, the Navy's job was

done. The Peruvian Navy had been destroyed and its ports occupied. All that was left for

the squadron was to provide transport for the Army to return to Chile and to bring

supplies, ammunition and replacements for the troops that had to remain behind. After

careful consideration, President Pinto appointed Patricio Lynch, promoted to Admiral, as

military governor of Peru. In spite of nationalistic resentments and his former command of

the unpopular expedition to the North coast, Lynch was to rule Peru with fairness and

honesty. For three years Lynch was in charge of the occupation Army, of Peruvian

administrators, of ship's movements in Peruvian waters, and of peace negotiations. His

administration was so efficient that it has been said that he was the "best Viceroy

of Peru".

Chilean historians have been overly critical of naval operations during the War of the

Pacific. Foreign observers have praised the naval campaigns as examples of good judgment

and ability. The Navy took the initiative and once it established control of the ocean in

a region where the cities were surrounded by deserts, it was a questions for attacking the

Peruvian positions as if they were islands. Furthermore, although it seems clear that a

naval ship that engages a vastly superior enemy is destined to fail, the fight between the

Covadonga and the Independencia off Punta Gruesa, shows

that there are exceptions. Once supremacy at sea was established, Chile took control of

the war. This control would not have been possible without the dedication to duty that

Prat and his companions demonstrated at Iquique.

<< 2: Independence || 4: Civil War >>