6: Agua Prieta

<< 5: Naco || 7: Other Towns >>

A Thursday late in October in 1992. I decided to go to the library and

municipal complex in Agua Prieta, and then cross back and go to the city and Cochise

College libraries in Douglas. Since I had just been to the library in Nogales, Sonora, I

figured that the library in AP, as Agua Prieta is known familiarly in both northeastern

Sonora and southeastern Arizona, would open at 10 or 10:30 A.M.

I got to the library, about 6 blocks south of the border in a small house,

at about 10:25. The sign said that it was open at 10, but the door, with wrought iron in

front of it, was locked. A passer-by told me in English that the library was really not

open until about 4, and gave budget cuts as the reason.

What to do? I did not want to cross the border twice in one day. Fifty

miles from Sierra Vista, and not having worked since stepping out of computer contracting

in June, I did not want to spend money to try again another day. The weather was very

good. So, I decided to walk as far east, and then as far south, as AP goes.

I first stopped at the city complex, about 6 blocks east. I went into the

auditorium. There were three men and two women at the front, and an audience of about 40.

From what I could tell, what I was at was a hearing on features of education for children

in the 4th through 6th grades of the schools. The federal government

runs all schools in Mexico except preschools, universities, and specialized technical

schools, so input on schools is taken through forums and hearings. This is the same as by

city councils and boards in the United States.

Then, I walked east to 20 de Noviembre, which would be 20th

Avenue if it followed AP's regular street numbering system. November 20, 1910 was the day

that Madero called for the Revolution to start, after he escaped house arrest by Díaz in

San Luis Potosí in central Mexico, and crossed into Texas. I walked 7 blocks south from

P.E. Calles to 13th St. East of 20 de Noviembre, the streets were simply tracks

plowed into the desert by bulldozers or road graders, and maintained by the tracks of

vehicles driving on them afterwards.

As I walked east, houses became smaller and smaller. What was I doing

worrying about when I would make my next $180 a day, in an area where people were worrying

about making $40 a week? At 43rd Ave., a small army base. Originally, the base

was located out of town, as the Constitution of 1917 says bases are to be, but AP had

grown so fast there was still a long way to go before I reached the development that I saw

at the east end of town, and a little to my north.

I got to the development, at about Calles and 50th Ave. The

north half was a subdivision of houses, as I had lived in and seen in California. The only

things missing on each house were a cedar-shake roof, for which it is too dry in Sonora as

well as Arizona, and one of the side yards. The south half was a public housing project.

The streets in both halves were paved. Was I seeing the future of housing north of the

border, as living conditions keep getting worse?

After getting something to drink at the Tecate convenience store where the

subdivision and the project meet, I turned south towards Highway 2. To go straight, I went

through a stand of desert, picking my way among the short creosote bushes, and catclaw and

whitethorn acacias. It was higher than the town to the north and west. A good place for

Pancho Villa to camp with his troops, and park his long-range artillery, when he came to

Agua Prieta almost 77 years before.

On the highway, there was a social hall, run by the Rotary or another

service club. The sign said that the band Blanco y Negro would soon perform there. Instead

of following Highway 2, because it swings southward as it goes west, I went straight west

to 20 de Noviembre. Al poniente, to the west, the streets were unpaved and not

well-graded, but the occupants could afford to buy Blazers, Explorers, and similar

vehicles at some point in time, and keep them maintained. Good to carry large numbers of

children, and also to carry large quantities of goods bought in shopping, this is why so

many of the vehicles from Mexico seen in Sierra Vista and Tucson are four-wheel-drive

vans.

I turned north on 7th Ave. After walking by the Zenith plant

and the cemetery, and going one or two blocks west, I got to the library at about 3:15.

The library was open by then. On the wall, the text of the Plan of Agua Prieta of 1920.

But, no books of interest. There may have not been any, or the person at the library may

have thought that I was looking for books in English. Before it closed that night, I got

to the Cochise College library west of Douglas. It had two books which said that Pancho

Villa had probably lost 3,500 killed, wounded so they could not follow him further, and

deserted when he came to Agua Prieta.

This is a summary of what happened in AP and with its visitors, before,

when, and after Villa came to the area in 1915.

Agua Prieta means "dark water". Likely, it was named after the

Rio de Agua Prieta, a usually dry stream that runs south of town. Founded at the same time

as Douglas across the border in 1901, it was the point of exit from Mexico for copper from

Nacozari bound for Douglas to be smelted, and of entrance for supplies bound for the mines

of Nacozari.

As Nogales and Naco, its location on the border made Agua Prieta

attractive to rebels looking for customs revenues to help them continue their operations.

Agua Prieta was the first town on the border to be taken by rebels, in April 1911. Stray

shots killed Americans, including a worker in the Douglas railyard, and President William

Howard Taft tried to get Americans to leave border areas in the name of preserving

neutrality. Four days later, Agua Prieta was recaptured by federal troops. By June, the

rebels had removed Porfirio Díaz from Mexico, after taking the much bigger town of Ciudad

Juárez, across from El Paso 250 miles to the east.

After Huerta overthrew Madero, Plutarco Elías Calles held Agua Prieta for

the Constitutionalists, under Venustiano Carranza and his chief general, Alvaro Obregón.

He was helped in keeping the federals out in 1913 by bombings from a Douglas flying club

secretly supported by the U.S. Army. These were the first bombings done by aircraft

anywhere in the world.

Huerta did not fall rapidly, as Díaz had. It took until the summer of

1914 for Obregón, operating from Sonora and the Gulf of California and Pacific coasts,

and Villa, operating from the state of Chihuahua and points farther south, to force Huerta

from Mexico City. Soon, Villa split from Carranza and Obregón.

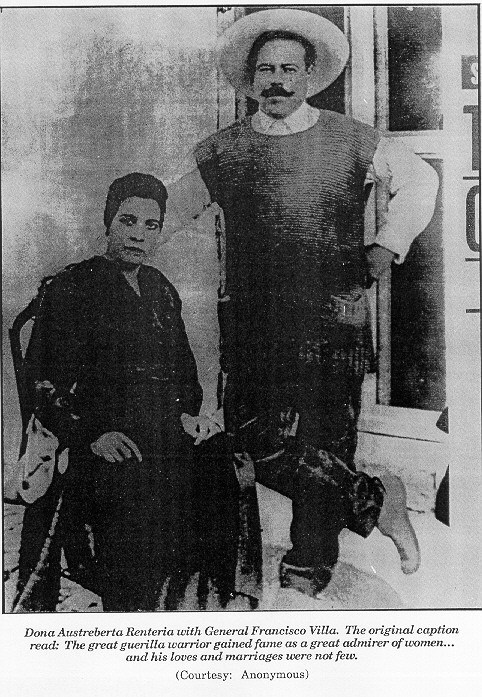

Villa is the greatest guerilla fighter the North American continent ever

produced.  Only

Geronimo comes anywhere close. Villa was also good in surprise attacks, as on Juárez

against Díaz, and on the city of Torreón, Coahuila against Díaz and Huerta.

Only

Geronimo comes anywhere close. Villa was also good in surprise attacks, as on Juárez

against Díaz, and on the city of Torreón, Coahuila against Díaz and Huerta.

However, Villa's skills did not carry over to large, pitched battles. Villa would not

listen to the advice of the generals who were loyal to him, including Felipe Angeles, who

had studied at the military academy in France. Obregón studied the battles of World War I

beginning in Europe. Early in his campaigns, he used German advisors. In April 1915,

Obregón moved into the town of Celaya, about 200 miles northwest of Mexico City, and

entrenched it. In two battles, Villa sent waves of troops toward the trenches, and

Obregón decimated them. Northwest of Celaya, Obregón moved into and entrenched La

Trinidad, near the city of León and the city of Aguascalientes, with the same results. By

October, Villa could count on only 6,700 men, instead of the 20,000 men in his Division of

the North, with whom he had started 1915. By that time, Villa held the north central parts

of Mexico, and his ally José Maytorena held most of Sonora and the west coast. Obregón,

under his political leader Carranza, held the northeast and central parts. The southern

parts were held by Emiliano Zapata and his supporters.

Calles was still holding Agua Prieta, in the name of Carranza. In the

north, Agua Prieta stood out like a sore thumb. If Villa could take Agua Prieta, he could

easily link with others holding towns or areas across from California or Texas, and take

the whole border.

Elías Torres, in his book written about Pancho Villa in 1933, says that

Villa brought only 3,000 men to Agua Prieta. Perhaps Villa brought the others as reserves.

However many he brought, they came from Chihuahua to Sonora through the difficult Cañon

del Púlpito (Needle Canyon). In one of the most difficult marches in military history,

they came through the canyon as winter weather was starting in October, without

provisions.

Calles was on his own, with 750 men. All around him in Mexico were Villa

and his allies. It was a few blocks north if he wanted to cross, but he did not want to

endure the detention, and the disgrace in Mexico, that Kozterlitzky had gone through 2

years earlier in Nogales. Besides, his mentor was Obregón, the victor over Kozterlitzky.

It would have been physically impossible for Obregón to come to his aid himself through

Mexico, and politically impossible from the north.

The politicians came to a solution for him. President Woodrow Wilson

recognized Carranza as the de facto leader of Mexico. Carranza stopped his own

covert support, and that of the Germans, for Mexicans fighting racial conflicts with

different groups of Americans in and across from Texas. In return, 3,500 troops got to

cross the Rio Bravo at Piedras Negras, Coahuila. Before they boarded the train at Eagle

Pass, Texas for Douglas, they saw the river as the Rio Grande. Obregón stayed in central

Mexico. In Douglas, American troops made sure that they crossed to Agua Prieta, and gave

them electricity for their searchlights. Once across, they were in close quarters, for

Calles had fortified an area 800 by 600 meters (2,624 by 1,968 feet), and abandoned the

area to Villa. Calles did this to allow the attackers little room to maneuver. In case the

Americans could not stop Villa if he attacked from that way, Calles even fortified the

side facing Douglas. On October 31, when Villa learned that the United States had

recognized Carranza, he still resolved to take Agua Prieta. He could not attack it from

the south, in case his long-range artillery overshot it and crossed into Douglas, and

invited American retaliation.

All through October, men kept leaving their homes in Chihuahua to join

Villa. Once the rumors became clear that they were going to AP, 4,000 people joined the

Army in Douglas, as spectators.

Calles divided the fortified area inside into four sectors. One was

commanded by Lázaro Cárdenas, who had defeated an advance patrol of Villa's outside a

few days earlier. The others were led by Fimbres, Ancheta, and Quevedo. At 2 P.M. on

November 1, Calles fired his artillery, to determine where Villa had concentrated his

heavy weapons. The duel took place for two hours.

At 8 P.M., Villa attacked the sector headed by Cárdenas, and was quickly

repulsed. He tried attacking all four sectors, at 10 P.M. This time, the searchlights were

turned on, so the attackers were easily identified and mowed down.

Villa's attacks ceased at 3 A.M. The troops of Calles recovered 223 dead,

and 376 wounded. This does not include the number wounded that stayed with Villa's force,

who died later, or deserted. Francisco Almada estimates that Villa took 1,000 casualties

overall.

By November 5, Villa had retreated to Naco. Blaming the United States for

his defeats, he issued a manifesto from there alleging that Carranza would accept a

$500,000,000 loan from the United States, reimburse Americans for all losses suffered in

the Revolution, and accept American control of the railroads in Mexico until it was paid.

With the troops he had left, he headed to Fronteras, south of Agua Prieta. He was defeated

near there. He turned south and west to Hermosillo, which the Constitutionalists under

Manuel Diiguez of Cananea had taken from Maytorena on November 17. Five days later, he was

repelled from Hermosillo. After that, Villa added that the United States would get oil and

port concessions from Carranza, and approve his treasury, foreign, and interior ministers.

He returned to the state of Chihuahua, but not before killing 77 civilians in the town of

San Pedro de la Cueva, east of Hermosillo.

The allies of Carranza, Obregón, and Calles rapidly took Nogales, Cananea,

Naco, and the other towns of Sonora. They also took the city of Chihuahua, so Villa could

not return to the house of 50 rooms that he had built just a year and a half earlier.

Looking for arms and revenge against the United States for his defeats, he raided

Columbus, New Mexico on the border about 150 miles east of Douglas on March 9, 1916, an

action much more publicized in both the United States and Mexico than the battle of Agua

Prieta. Eighteen Americans died, but the raiders lost at least 162 of their number. Villa

remained a guerilla in north central Mexico until 1920.

Obregón was Carranza's secretary of war, until he resigned in 1918 to run

for president of Mexico in the elections of 1920. After he was summoned to Mexico City to

testify in the treason trial of an ally, it became obvious that Carranza was not going to

let him win against the successor he had picked. Calles and other generals met and issued

the Plan of Agua Prieta, formally the Organic Plan of the Movement for Revindication of

Democracy and the Law, in April 1920. Obregón escaped the capital. Commanders supported

him, and removed Carranza. Obregón's provisional president under the Plan of Agua Prieta,

Adolfo de la Huerta, made peace with Pancho Villa in 1920. When Obregón himself became

president, he made peace with the successors of Zapata in the south. Obregón remained

president of Mexico until 1924, when he was succeeded by Calles. Obregón was assassinated

in 1928, before he could begin a second term. No president has died in office, and no

president-elect has died waiting to take office, until then.

Pancho Villa built this house in Chihuahua City in 1913, but

his enemies forced him out in December, 1914.

After Obregón's death, Calles did not assume the presidency again, but he

tried to rule through handpicked successors. The fourth of these was Cárdenas, one of his

seconds-in-command at Agua Prieta, who took office in 1934. Cárdenas was much more

liberal in his politics than Calles. When he got enough support in 1935, he forced Calles

onto an airplane to Sinaloa, and eventually to exile in California. Cárdenas is best

known for nationalizing the Mexican oil industry in 1938. Today, all oil in Mexico is

produced, and all gasoline distributed, by Petróleos Mexicanos, or PEMEX.

The area of Agua Prieta became a municipality of its own in 1916,

separating from Fronteras. AP was the last town that José Escobar tried to take in his

rebellion of 1929, before he crossed the border. Agriculture in the area includes wheat,

beans, corn, and forage crops. There is raising of both dairy and beef cattle, and

beekeeping. Factories make clothing, furniture, machinery, automotive equipment and parts,

tools, gypsum, and electrical equipment and accessories. There are some pharmacies,

restaurants, and bars near the border. There are some stores selling Western wear (in

Mexico, norteño), and a fairly large tile store near the city complex. Maps first

showed Highway 2 as paved east to Janos, Chihuahua, in 1984. During the 1980s, Agua Prieta

suffered much gang, election, and drug violence. A tunnel for smuggling drugs across the

border to Douglas was found in May 1990. The bodies of 12 were found in a well, possibly

killed in an unsuccessful attempt to keep them from disclosing the location of the tunnel

after they had built it. The federal government had the entire city police force fired,

and replaced it with police from the interior until the force could be staffed locally

again.

The population of Agua Prieta was counted as 40,769 in 1986. Most estimates placed the

number of people in 1992 at 85,000, and today in 2000 at as many as 135,000. As Nogales

and Naco, people keep coming to Agua Prieta from places in the interior of Mexico that are

unable to support them.