4: The Admirable Campaign

<< 3: "War to the death" and the meeting at Santa Ana || 5: Antonio Ricaurte at San Mateo >>

I

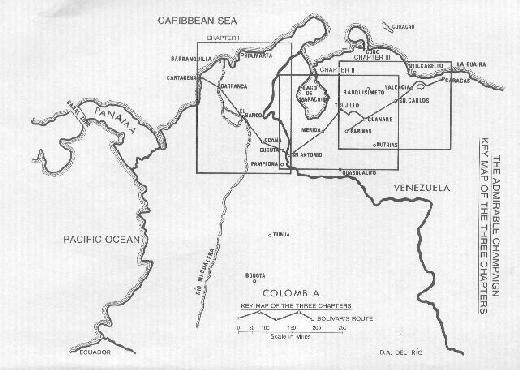

In the annals of the military history of the world perhaps one of the most amazing feats—for brilliant tactics,

swiftness of action and superb and daring strategy—is the most aptly named "Admirable Campaign" of Simón

Bolívar, the Liberator of South America.

Starting with a mere handful of seventy men (later greatly increased), and lacking the essentials of

equipment, supplies and food, he nevertheless, in the short period of seven and one-half months, succeeded in

defeating a superbly equipped enemy ten times greater in numbers, and in liberating Venezuela.

When this stupendous undertaking, during which Bolívar crossed and re-crossed the mighty Venezuelan

Andes, is better known, history will rank this achievement with the crossing of the Alps by Hannibal and

Napoleon, although the Alps are lower.

At the end of the year 1812, Bolívar, then twenty-nine years of age, had arrived in the newly independent

city of Cartagena, Nueva Granada (now Colombia), as a refugee, having barely escaped with his life from his

native Caracas, where Domingo Monteverde, Captain-General of that Venezuelan Spanish colony had confiscated

all of his properties.

The future Liberator had come to Cartagena to enlist the help of the people of Nueva Granada in

liberating Venezuela from its Spanish oppressors. It was at this time that Bolívar issued his famous public

declaration (Manifesto of Cartagena), considered a monument of military and political rhetoric, which ended with

the following words:

"Let us hasten to break the chains of those victims who groan in the dungeons, ever-hopeful of

rescue. Do not betray their confidence. Be not insensible to the cries of your brothers. Fly to

avenge the dead, to give life to the dying, to bring freedom to the oppressed and liberty to all!"

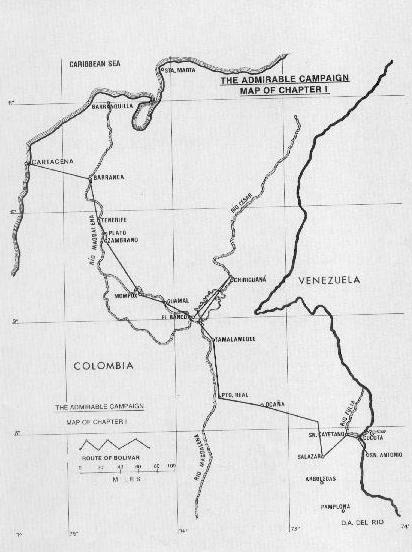

The response to this impassioned appeal, however, was his appointment as commandant, with the rank of

Colonel, of the insignificant military post of Barranca (now Calamar), situated on the left bank of the Magdalena

River. It had a garrison of 70 men, which he succeeded in increasing to 200 by securing volunteers.

On the 23rd of December, 1812, he proceeded a few miles up river to the town of Tenerife on the opposite bank

and took its fort by a daring assault. This fort, perched on a small hill and strongly garrisoned, had until then

effectively cut off all communications between Cartagena and the interior provinces of Nueva Granada.

Continuing upstream and southward from Tenerife, Bolívar overcame the Spanish detachments

entrenched in the river towns of Plato and Sambrano, and entered the city of Mompox on December 27th. Here he

not only obtained food and other supplies, as well as a few river boats, but also managed to increase his small army

to 500 men. Proceeding upstream, he took the small settlement of Guamal three days later, and by January 1, 1813,

had arrived in the town of El Banco. This strongly fortified position had a garrison of 400 troops, mostly Spaniards

recently arrived from Cuba, who had evacuated the town the day before, fleeing north in river boats through the

Sapatosa lagoon and the Cesar River toward Valle de Upar and Santa Marta. However, Bolívar marched his troops

overland ahead of the slow-moving boats, and succeeded in defeating the enemy at Chiriguana. Here he took

considerable booty, including eleven river boats, and a large number of prisoners. Again retracing his steps to the

Magdalena River, he bypassed El Banco and occupied Tamalameque, some 20 miles upstream. Beyond Puerto Real

(today: GAMARRA) which he captured on January 6, 1813, the tortuous road over the mountains led to the city of

Ocana, gateway to the border town of Cúcuta and to Venezuela.

Bolívar entered Ocaña on the 8th of January. Thus in fifteen days (or less time than it would have taken a

courier to travel from Cartagena to Ocaña), he had liberated an entire province and destroyed or dispersed enemy

forces ten times greater than his own meager troops. He remained at Ocaña one month, reorganizing his forces,

now reduced to only 450 men through desertions, disease and the acute shortage of food and clothing. Moreover,

his financial resources were non-existent; thus, the soldiers had received no pay. The obstacles and difficulties

confronting Bolívar would have discouraged any leader not possessed of his daring and determination.

The next goal, Cúcuta, was at the other side of a formidable mountain barrier (a secondary range of the

Andes). Here Bolívar had to face the Spanish Colonel Ramon Correa, who was waiting for him with 1,300

excellently trained and equipped troops. Correa, while retaining 750 men at Cúcuta, had strategically distributed

other battalions in almost impregnable locations guarding the mountain passes through which Bolívar's troops had

to travel. He had sent part of his vanguard of 200 men to San Cayetano, facing the Zulia River (about 300 yards

wide); had placed some 240 troops a little farther away at Salazar and over 100 at the heights of La Aguada.

Beyond the border, on the Venezuelan side, Bolívar had to contend with the following enemy contingents:

At Barinas and Alto Apure, under Commander Antonio Tiscar, about 2,800 men

At San Fernando and Guasdalito, under José Yañez, 1,200 men

At Calabozo, under José Tomás Boves, perhaps 1,000 men

Moreover, between Caracas and the eastern regions of Venezuela, there were garrisoned over 4,000 additional

enemy troops. Thus, in all, including the forces under Correa at Cúcuta, his next objective, Bolívar had to contend

with an enemy ten' to twenty times stronger than his own forces—in his determination to liberate Venezuela.

On January 23, 1813, fifteen days after entering Ocaña, Bolívar received an appeal from both the

Governor and the Military Commander of the Pamplona Province of Nueva Granada, adjoining Cúcuta, to come to

their assistance, as they feared an attack from the Correa forces at any moment.

As we will see later in [The Admirable Campaign: II], Colonel Manuel del Castillo, Military Commander

of Pamplona, was jealous of Bolívar's victories, and when the future Liberator was appointed Chief of the Forces of

the Union over him, he refused to follow orders, and nearly wrecked Bolívar's plan to liberate Venezuela.

On February 9th, after receiving permission from Cartagena to help Pamplona, Bolívar sent his vanguard

toward the small settlements of La Cruz, San Pedro and Salazar. At this latter point the mountain trail divided,

going toward Cúcuta in one direction and toward Pamplona in the other. The task of moving even so small a force

as 450 men toward Pamplona was formidable. The only mule trail between Ocaña and Salazar, after crossing some

36 miles of rugged and arid table-land cut by a number of deep gullies, ascended the foothills of the Sierra through

canyons and crevices carved through the giant rocks by the mountain streams. The troops followed a path which

went along the bottom of the ravine, made wet and slippery by the torrential rains of the region, and then climbed

sharply up the jagged rocks of the mountainside to the cold and desolate top of the range. Most of the soldiers,

accustomed to the torrid climate of Mompox and Cartagena, suffered greatly from these violent changes in

temperature. Only the superb leadership of Bolívar held them together.

It took the small patriot force six days to reach the canyon of La Aguada, a distance of only 40 or 50 miles

"as the crow flies". The road through La Aguada transversed a deep ravine defended along the top by the platoon of

100 men sent there by Spanish Colonel Correa. The position of the enemy was so formidable that this small force

could stop an army. But here Bolívar's generalship won the day. He sent ahead a spy who informed the enemy that,

not only were Bolívar's troops on their way to attack them, but a large body of patriot detachments was

approaching from Pamplona to take them by surprise from the rear. At this news the Spanish garrison fled in panic

toward Arboledas and Cúcuta, swiftly pursued by the vanguard of the patriots.

Thus, having succeeded in preventing an attack on Pamplona, Bolívar decided, upon reaching the small

town of Salazar, to proceed from there toward Cúcuta. Leaving these small scattered contingents of the enemy far

to his right, he accelerated his march toward San Cayetano, which was situated on the right bank of the Zulia River

only 10 miles from Cúcuta. On February 25, 1813, after a brief and bloody skirmish when the patriots crossed the

river, the Spanish garrison at San Cayetano fled toward Cúcuta, leaving the dead and wounded behind. At San

Cayetano Bolívar received some ammunition, sent by the Nueva Granada Government, and his rearguard was

reinforced by a detachment of 126 soldiers sent by Colonel Castillo from Pamplona. Even with these new troops,

his small force numbered only 500 soldiers because of desertions, sickness and casualties.

Moving swiftly from San Cayetano, Bolívar arrived at the hills on the outskirts of Cúcuta on February

28th, where Correa and his troops were waiting for him. Victory was won by Bolívar in four hours of fierce

combat, but only after the future Liberator ordered a bayonet charge to end the stubborn resistance of the enemy.

One of his lieutenants, Colonel José Félix Ribas, distinguished himself for his bravery in this assault and was

chiefly responsible for the victory. Bolívar collected large quantities of arms, ammunition, food and other supplies

abandoned by the enemy in their precipitous flight, and also from the well-stocked warehouses and stores in the

city. The patriots pursued the fleeing remnants of Correa's army across the border to the Venezuelan town of San

Antonio.

It was here, on March 1, 1813, that Bolívar issued a proclamation to the Venezuelans which read in part:

"I am one of your brothers from unfortunate Caracas. Having been miraculously spared by the

Almighty from the hands. of tyrants, I have come to bring you Liberty, Independence andJustice,

generously protected by the Governments of Cartagena and the Union..."

And in a proclamation to his troops he said in part:

"In less than two months you have carried out two campaigns and have started a third, which begins here and must

end in the country that gave me life! America expects its Liberation and Salvation from you, Soldiers of Cartagena

and the Union. Fly to cover yourselves with glory, winning the sublime name of "Liberators of Venezuela!"

Bolívar's foremost historian, Dr. Vicente Lecuna, commenting on the above proclamation, says:

...Language remarkable for its audacity and greatness. With incredible swiftness Bolívar liberated Venezuela and,

although the fighting continued for another twelve years, his soldiers fulfilled the promise of. his prophetic

proclamation."

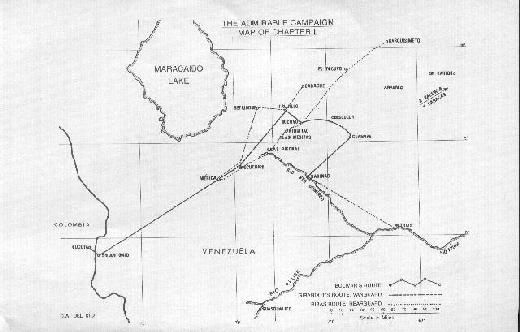

After his defeat, the Spanish Commander Correa fled to Mérida and from there to Trujillo. Meanwhile,

Bolívar returned to Cúcuta, where he received a promotion to Brigadier-General from the Nueva Granada

Congress for his splendid victory.

II

The future liberator remained at Cúcuta nearly eleven weeks, not only on account of the insubordination

of one of his officers, but also because he could not leave the territory of Nueva Granada to liberate Venezuela until

he received the necessary authorization from both the Government of Cartagena and that of Nueva Granada.

Colonel Manuel del Castillo,(1) formerly his equal in rank but now his subaltern, commanded the Nueva

Granada forces in the Province of Pamplona, consisting of about 300 men. After Bolívar's promotion to

Brigadier-General, Colonel Castillo was ordered by the Government to place his forces under Bolívar's command.

This he did reluctantly; moreover, he refused to cross the border into Venezuela, deeming this a fantastic venture,

fraught with danger and doomed to failure beforehand, because of the insignificant number of patriot troops that

would be facing an enemy ten times their strength. Bolívar tried in vain to reason with him, and after two months

of acrimonious correspondence between the two commanders and their governments, Castillo was relieved of his

command.

Bolívar was finally granted permission to cross the border into Venezuela, with the stipulation that he

liberate only the Provinces of Mérida and Trujillo. This authorization did not reach him until May 7th; but with it

the Nueva Granada Government sent to Cúcuta supplies of guns and ammunition, while the Cundinamarca

Government at Santa. Fe, (Bogotá) sent him 150 volunteers.

In their number were many young officers(2) who later received the greatest honors that history can bestow.

While Bolívar was still at Cúcuta, he had received news that the Spanish Commander Correa had fled from Mérida

to Trujillo with the remnants of his battered forces, and that the former city, freed from the enemy and anticipating

the arrival of Bolívar, had declared its independence. Thereupon Bolívar promptly sent Dr. Cristobal Mendoza, an

able administrator and wise counselor, to organize the government of that province.

On May 14, 1814, Bolívar left Cúcuta for Mérida (a distance of about 175 miles by mule trail), taking

with him only 500 men. Colonel Castillo, continuing his animosity toward Bolívar, had succeeded in withholding

100 soldiers, whom he took with him to Bogotá.

The city of Mérida is located at an altitude of about 5,300 feet in a long narrow valley, walled in from both

sides by the towering Venezuelan Andes. Bolívar's vanguard entered the city on the 18th, and he himself arrived

on May 23, 1813. It was at Mérida that Bolívar was proclaimed "LIBERATOR". While there, he persisted in his

plans to reach Caracas, and on May 26, 1813, wrote to the president of the Nueva Granada Government with this

prophecy:

"Within two months we will see the Republic of Venezuela fully liberated, provided that the

Executive Power authorizes me to act according to, circumstances".(3)

Bolívar remained at Mérida a little over two weeks, during which time he organized the local government.

However, his most urgent task was to provide for his small army, now reinforced by additional volunteers and

aggregating nearly 1,000 men, about half of whom lacked training and proper equipment.

At Mérida Bolívar received news of the invasion of eastern Venezuela by a small group of young officers

under General Santiago Mariño. This he considered most propitious, as it would turn the enemy's attention to that

part of the country, diverting in that direction some of. the Spanish forces now facing him. Bolívar also received

information that Correa and 300 troops were entrenched at Betijoque (a small town halfway between Trujillo and

Maracaibo Lake to the west), awaiting a reinforcement of 400 men who were at Carache, about 25 miles north of

Trujillo. He further' learned that some 200 enemy troops had recently arrived at this latter city from Barinas.(4)

The military plans of the Liberator were bold but simple. He had to tackle separately, first Correa at

Betijoque, and consisting mainly of volunteers from the torrid climate of Mompox and Cartagena, suffered greatly,

scaling mountains 13,000 feet high and then suddenly descending to valleys of only 2,500 to 3,000 feet in altitude.

After engaging and defeating Correa at the heights of Ponemesa near Betijoque, Girardot and his

vanguard entered Trujillo on June 10, 1813. Correa escaped, and fleeing with the remnants of his forces, scarcely

100 men, sought refuge in the woods of the Maracaibo Lake. The same day Bolívar set out from Mérida, leaving

behind his rearguard under Colonel José Félix Ribas, and arrived at Trujillo four days later, on June 14th.

Here Bolívar sent Girardot to destroy a column of 500 enemy troops under Spanish Frigate Captain

Manuel de Canas, entrenched in the impregnable heights of Obispo near Carache (25 miles north of Trujillo). On

June 17th, Canas was dislodged from his positions, and defeated after a bloody battle.

Girardot captured 100 prisoners and a large quantity of food and arms. Upon their return to Trujillo five

days later the victorious patriot columns were met at the gates of the city by the Liberator and his entourage,

together with a wildly enthusiastic multitude.

It was at this city, on June 15, 1813, that Bolívar issued his famous "WAR TO THE DEATH"

proclamation, considered by historians as perhaps the greatest and most transcendental of his revolutionary

thoughts, which culminated in these formidable words:

SPANIARDS AND CANARIANS:(5) If you do not take an active part on behalf of the freedom of

the Americas you will be shot even if found innocent. AMERICANS:(6) your life will be spared

even if you are found guilty.

To crush the incipient revolt of the natives, the Spanish armies had resorted to terrorism and mass

slaughter. No prisoners were taken: when the Spanish forces entered a town that had sided with the republicans,

the hapless inhabitants were massacred, the women raped, and the buildings looted and burned. The town's leaders

were tortured by cutting off their ears, cheeks and noses, and then drawn and quartered. Bolívar failed in his

repeated efforts to have the Spanish Generals stop this savagery, whereupon he was forced to go against his lofty,

humanitarian principles and issue the above-mentioned "WAR TO THE DEATH" proclamation.

Before proceeding further, let us go back to Mérida, whence the rearguard of the Liberator's army under

Ribas had been instructed to proceed as soon as possible to Bocono and join the vanguard there. Ribas left Mérida a

few days after Bolívar, and crossing the high peaks of Las Piedras Valley, continued up the Santo Domingo River

on the road leading directly to Barinas. Following Bolívar's instructions, he turned north here, climbed the range

and descended the other side, heading toward Niquitao and Bocono. In the vicinity of Niquitao Ribas was joined on

June 30th by Lieutenant Colonel Urdaneta, his second in command, who with an escort of 50 soldiers had brought

part of the baggage and other impedimenta of the rearguard.

At this juncture Ribas was informed by his scouts that a detachment of 500 enemy troops under Spanish

Commander José Martí was heading for Niquitao from Barinas: Frigate Captain Antonio de Tiscar, defending

Barinas with 2,600 troops, was alarmed by the news of Bolívar's invasion of the Provinces of Mérida and Trujillo,

and conceived the plan of trapping the Liberator and his small forces in the territory between the two cities. To this

end he sent a division to Yañez at Guasdalito on his rear,(7) two squadrons to Guanare in the north, and the Martí

Division to Niquitao, reducing his forces at Barinas to only 600 infantry and 500 cavalry.

Although Ribas commanded a rearguard numbering scarcely 350 men, upon learning of the approach of

the Martí forces, he retraced his steps and, by moving swiftly, covered the 40 miles separating him from Niquitao

on July 1st. The next day the small Ribas contingent reached the enemy force of 800 (not 500 as Ribas had been

wrongly informed), which was entrenched at Las Mesitas, a site protected by the enormous rocks of the foothills at

its rear. After a fierce assault, during which he used his small cavalry to attack the enemy from the heights on their

rear, Ribas achieved victory. He captured over 400 prisoners, together with their rifles, as well as a large quantity

of ammunition and supplies. To augment his forces, which had been reduced to 250 by the combat and the

strenuous march over the mountains, Ribas recruited 150 soldiers from his prisoners.

Meanwhile, after organizing the local government, Bolívar had left Trujillo on June 24th, with the

Girardot vanguard division. On June 21st the Liberator had sent revised instructions to Ribas to join him with the

rearguard at Guanare rather than Bocono. Bolívar's daring plan was to, surprise the Spanish forces at Barinas by

-attacking them from the rear, in lieu of taking the difficult route through the mountain passes toward Boconó and

Barinas (75 miles to the south), as the enemy expected. Crossing the Andes through a pass 11,000 feet high, he

arrived at Boconó on June 27th, where instead of continuing directly south, he turned in a northeasterly direction

toward Biscucuy and Guanare, a detour of over 50 miles. As Guanare is situated on the main road between Barinas

and Caracas, Bolívar's unexpected move effectively cut communications between those two cities and placed him at

the rear of the enemy.

At Guanare, upon hearing that Tiscar had considerably depleted his forces by sending the Martí Division

to the Andes, Bolívar instructed Ribas to dispose of Martí. Without waiting for the outcome of this encounter, or

for Ribas to join him as planned, he proceeded alone with the vanguard to attack Barinas, again relying on the

element of surprise.

On July 5th Spanish Commander Tiscar, upon learning of the defeat of Martí and the swift march of

Bolívar toward him, fled in panic from Barinas toward Nutrias on the Apure River (about ,100 miles to the

southeast). Bolívar entered Barinas on July 6, 1813, finding there 32 light artillery cannons and a large quantity of

rifles and ammunition which had been abandoned by the enemy in their hasty retreat.

The Liberator immediately sent the vanguard under Girardot in pursuit of the fleeing Tiscar forces. The

patriots moved rapidly over the plains, which had been transformed by the rainy season into small lagoons and

almost impassable swamps. Nevertheless the distance of over 90 miles was covered in just three full days and

nights. Girardot succeeded in completely routing the remnants of Tiscar's troops, and took 400 prisoners with their

rifles and other equipment. However, Tiscar and his lieutenant, Nieto, practically alone, succeeded in escaping by

boat, down the Apure River.

From Barinas, Bolívar wrote to the President of Nueva Granada on July 10, 1813, saying in part:

When I approached Mérida, I had only 500 men to oppose 3,000 under Correa at Carache and

Tiscar at Barinas. We have destroyed these armies, and left to face us are only the contingents of

500 to 600 men under the Canarian Gonzalez at Tocuyo (about 150 miles north of Barinas).

These must already have been defeated by our rearguard following my instructions to its

Commander.(8) After this, the road to Caracas will be free of enemies!(9)

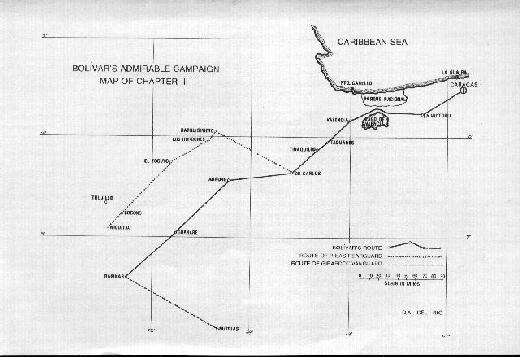

III

Upon arriving at Barinas, Bolívar had sent Girardot and his vanguard toward Nutrias, on the Apure

River, in pursuit of Tiscar. On July 9, 1813, he instructed Ribas to turn north with the rearguard and destroy the

Spanish forces at El Tocuyo(10) which were menacing Guanare.

On July 16th the Liberator left Barinas. Reaching Guanare on the 17th, he received information that the

Spanish forces at El Tocuyo under the command of Pedro Gonzalez de Fuentes, the Spanish Governor of Barinas,

had left that town on their way to Barquisimeto. He then instructed Ribas to go after Fuentes, but to avoid

Barquisimeto, where Bolívar feared that the commander might encounter a superior Spanish force. After defeating

Fuentes, Ribas was to bear east and proceed to Araure, where he would join with other patriot forces.

It was Bolívar's plan to avoid dispersing his small forces in territories away from his main goal, Caracas.

With his entire strength consolidated at Araure, he could destroy any enemy concentrations threatening him either

from Barquisimeto or from San Carlos in the north (his next target on the way to Caracas). It was a stroke of luck

that Araure, strategically located about 60 miles north of Guanare and 50 miles south of San Carlos, had declared

its independence on July 10, 1813, and had organized a small cavalry force to add to the patriot army. Only two or

three days before, Spanish Commander Oberto and his garrison of 300 troops had evacuated Araure, heading for

Barquisimeto to join an infantry and cavalry column sent there from Coro. On reaching Barquisimeto Commander

Oberto was met by the contingents of Pedro González de Fuentes, which had arrived from El Tocuyo, and by the

remnants of the Cañas forces defeated at Carache. Thus reunited, the three commanders, with a force of 909 men

(800 cavalry, 109 cavalry and three cannons) decided to attack Ribas.

On the morning of July 22nd, the Ribas forces, aggregating only 450 infantry and 80 cavalry, met the

enemy at Los Horcones (about 20 miles south of Barquisimeto). The small Ribas contingents were twice repulsed,

but their third attack succeeded in routing the enemy. Losses on both sides were about 100 dead and 100 wounded.

That very day Ribas entered Barquisimeto. Oberto, González and Cañas escaped with an escort of only 15 cavalry

soldiers through San Felipe.

Meanwhile, on July 21, 1813, Colonel Urdaneta had arrived at Araure with a patriot force of 100 infantry

and 50 cavalry. Bolívar joined him there on the 24th. The next day the Liberator wrote to Dr. Camilo Torres,

President of Nueva Granada, saying in part:

Having been informed of the defeat of Captain-General Monteverde in eastern Venezuela by.

Generals Piar and Bermúdez (under General Mariño), I fear that our illustrious brothers in arms

from Cumaná and Barcelona may liberate Caracas before we arrive there, although I hope that I

will be the first Liberator to reach its sacred ruins.

Two days later (July 27th) Bolívar and the Girardot vanguard, which had arrived the day before, left Araure to

occupy San Carlos. Before leaving Araure, the Liberator appointed Dr. Cristóbal Mendoza (who up to then had

been Governor of the Province of Mérida) as Governor of the Province of Caracas, with special instructions to

organize the Treasury and the Courts of justice in the territories he had freed.

Up to that time, Spanish Colonel Julian Izquierdo had been stationed at San Carlos with 1,200 troops.

However, upon hearing of the defeat sustained by Oberto at Barquisimeto, he and his Division immediately

evacuated the city, intending to join other forces under Captain-General Monteverde at Valencia.(11) On the way, he

decided to stop at Tinaquillo (30 miles northeast of San Carlos) to await reinforcements from Monteverde. This

stop was to prove fatal. For when Bolívar heard the news at midnight on July 29th, he immediately left San Carlos

with the Girardot and Urdaneta forces, numbering by then about 1,500. It is presumed, but not confirmed, that part

of the Ribas forces went with Bolívar, although Ribas himself, being ill, remained behind at San Carlos. On the

morning of the 31st, the calvary of the patriots met and clashed with the advance guard of the enemy at the

Savannah of Pegones in the Taguanes plains. However, after a skirmish of several hours (while the rest of the

patriot forces arrived), Bolívar perceived that Izquierdo and his troops were trying desperately to escape from the

plains of Taguanes toward the foothills of the Andes, seeking refuge in the mountains. Whereupon he ordered an

infantry battalion of about 200 men to mount the horses of a cavalry squadron behind the riders, and move swiftly

ahead of the enemy in a parallel line and, upon reaching the foothills of the Sierra, to attack Izquierdo's vanguard

while Bolívar's men disposed of their rearguard. After a bloody fight, the enemy surrendered en masse, having lost

five of their top officers, and Izquierdo, who was badly wounded, died that night. In this action Girardot and

Urdaneta greatly distinguished themselves.

The Battle of Taguanes was the coup de grace to all organized resistance by the Spaniards.

Captain-General Monteverde, en route to Tinaquillo with the reinforcements for Izquierdo, hastily retreated to

Valencia upon receiving the news of the defeat. From there he fled with the troops on August 1st, seeking

sanctuary in the Forts of Puerto Cabello.(12) In his panic, Monteverde left behind considerable military booty,

including 30 large artillery guns, emplaced in the main square of the city, as well as ammunition, foodstuffs and

many horses. Bolívar entered Valencia on August 2, 1813, sending Girardot on in pursuit of Monteverde. But it

was too late, as the latter had already reached the safety of the forts. The news of Izquierdo's defeat and the flight

of Monteverde created indescribable terror among the Spanish populace of Caracas. A battalion of 100 Spanish

volunteers deserted, abandoning all the defensive points of the city, while a garrison of 1,000 troops defending La

Cumbre, a hilltop on the road to La Guayra,(13) fled in panic. In one day desertions reduced the "veterans" battalion

of 238 Spaniards to 174.

Faced with this chaos, Manuel del Fierro, Provincial Governor of Caracas, and the other Spanish

authorities appointed a group of prominent men to negotiate a surrender with the Conqueror. Among the

Commissioners were two close friends of the Liberator: the Marquis de Casa Leon, who had prevented Bolívar's

incarceration in 1912; and Don Francisco Iturbe, who had then obtained from Monteverde a safe conduct for

Bolívar to leave the country.

At La Victoria, on the 4th of August, Bolívar signed a generous capitulation, and three days later entered

Caracas (43 miles away), to the acclaim of cheering masses, whose tumultuous welcome was expressed with

cannon and church bells, garlands of flowers and profuse display of flags.

On August 8, 1813, scarcely three months after crossing the Venezuelan border, and seven and one-half

months from the start of his campaign, Bolívar issued a proclamation at Caracas, which read in part:

Your Liberators have come from the banks of the mighty Magdalena (river) to the fertile valleys

of Aragua and to this Capital City,. ... we have defeated five armies, 10,000 strong, that

devastated the beautiful provinces of Santa Marta, Pamplona, Mérida, Trujillo, Barinas and

Caracas.

And which ended

...My Countrymen, your Republic has just been reborn under the auspices of the Nueva Granada

Congress, your auxiliary, that sent its armies, not to give you laws, but to re-establish your own,

which disappeared through the eruption of the barbarians that enveloped the Sovereign States of

Venezuela in chaos, confusion and death. Today your country is once more free and independent,

and raised to the rank of a nation. "This is—CARAQUEñOS—My Mission! Gratefully accept

the heroic sacrifices that my brothers-in-arms have made for your welfare-In giving you Liberty

they have covered themselves with Immortal Glory!

And on August 9, 1813, our Hero, who had sacrificed his great wealth and abandoned everything in life to

serve his country, made his first public declaration by which the world could know that he had no personal

ambition, issuing a proclamation ending as follows:

The Liberator of Venezuela renounces forever and declines irrevocably to accept any office

except the post of danger at the head of our soldiers, to defend the salvation of our Country.

Five months later, on the occasion of being solemnly proclaimed "Liberator of Venezuela", in an address

to the Caracas Assembly, he said in part:

Fellow Citizens—I have not given you Freedom; for this you are indebted to my fellow soldiers.

Behold their noble wounds which still bleed; recall to mind those who have perished in battle.

My glory has been in leading these brave soldiers. Neither vanity nor lust for power inspired me

in this enterprise. The flame of Freedom kindled this sacred fire within me, and the right of my

fellow citizens, suffering the ignominy of death on the scaffold or languishing in chains,

compelled me to take up the sword against the enemy. The justice of our cause united the most

valorous soldiers under my banners, and a just Providence accorded us Victory—I have

vigorously defended your interests on the field of honor, and I promise that I shall uphold them to

the last day of my life. Your honor, your glory will be ever dear to my heart—but the weight of

authority burdens me. I beg you to relieve me from a task which is beyond my strength. Choose

your representatives, your statesmen and a just government; and be assured that the armies that

have saved the Republic will forever protect Venezuela's Liberty and National Honor—and, in

taking leave of you, I promise that the general will of the people shall ever be my supreme law,

and that my people's will shall guide me in all my actions, even as the object of my efforts shall

be your Glory and your Freedom.

1. Manuel del Castillo Rada, born at Cartagena, was shot by Spanish General Pablo

Morillo on February 24, 1816.

2. Among those officers born in Nueva Granada were: Atanasio Girardot and

Luciano D'Elhuyar, (Girardot died in combat at Las Trincheras on September 30, 1813); José

Maria Ortega; Antonio Ricaurte (who died at the Battle of San Mateo on March 25, 1814);

Joaquin Paris; and Francisco de Paula Vélez. Two Venezuelan officers who were with Bolívar

deserve special mention: Rafael Urdaneta and José Félix Ribas. The latter, born in Caracas

September 19, 1775, was executed by the Spaniards on December 15, 1814. All of the New

Granadians were under twenty-two years of age. Of the Venezuelans, Ribas was the elder,

thirty-seven years old, while Urdaneta was only twenty-four.

3. This authorization was granted, and was received by Bolívar at Trujillo. It had the

limitation that three Commissioners being sent by the Nueva Granada Central Government were

to approve the decisions of the Commander-in-Chief in case of necessity. Just two months after

the Liberator left Mérida on June 10th, he entered Caracas in triumph on August 7th. Never was a

prophecy better fulfilled.

4. Barinas, capital of the province of the same name and gateway to the Llanos

(savannahs) is located about 100 miles southeast of Trujillo. Communication between the two

cities, was by mule trail through a steep and almost impassable canyon of the Andes, toward

Bocono and the plains.

5. Canarians: Natives of the Spanish Canary islands, situated on the northwest coast

of Africa, facing southern Morocco and Spanish Sahara.

6. Americans: Many of the native South Americans in the Spanish army had been

conscripted and compelled to fight the forces of the Liberator, who therefore decreed that their

lives would be spared if they were captured.

7. In a communication dated at Guasdualito, June 29, 1813, sent by José Yañez, head

of the garrison there, to his Commander, General Tiscar, Yañez acknowledged the instructions to

be ready to proceed to Cúcuta on the Nueva Granada border; he had 712 troops under his

command, of which 500 were infantry, 32 artillery, with two cannons, plus 180 cavalry.

8. Bolívar, when sending Girardot in pursuit of Tiscar, had ordered Ribas, on July

9th, to proceed with the rearguard to engage and defeat Gonzalez de Fuentes, the Spanish

ex-Governor of Barinas.

9. General Pedro Briceño Mendez, then acting as Secretary to the Liberator, wrote in

his memoirs about this campaign: "Bolívar with lightning action, conceived and executed his plans

of operations, organized the governments of the territories that had been liberated, and gathered

contingents of new troops, which while being trained had to be swiftly mobilized and engaged in

battle. With the arms and native soldiers and officers captured at Barinas, Bolívar promptly

created a battalion of "chasseurs" who had to go into combat before he had time to organize them

properly." —Victory crowned his efforts.

10. El Tocuyo: a small town about half-way between Trujillo and Barquisimeto on the

northeast, and about 50 miles north of Guanare.

11. Valencia: Second largest city of Venezuela, located about 55 miles northeast of

San Carlos and about 100 miles from Caracas.

12. Puerto Cabello: The seaport of Valencia, about 35 miles north of the city. The

forts are located on an island separated from the mainland by a narrow canal, the only means of

access being a drawbridge. When the bridge was up, the troops inside were virtually impregnable.

13. La Guayra: A principal port of Venezuela, about 20 miles north of Caracas.

<< 3: "War to the death" and the meeting at Santa Ana || 5: Antonio Ricaurte at San Mateo >>