6: The Sixties

<< 5: After WWII || Bibliography and Sources

When the ocean temperature and the land temperature are

right, fog rolls in from the

sea. Sometimes it is so thick that the world is enveloped in moisture, raining droplets so

fine that they seem suspended in mid-air. At times, the blanket of fog is

so thick that one can barely see the hood of a car. Eerily beautiful unless one

has an accident. The world turns gray; the flaws are masked. Sea fog evokes

thoughts of mystery and movies.

The sun comes and burns off the fog. All is revealed. Reality

returns—the beauty, the ugly, the benign, the mean—and

people have to adjust in the meantime. Only the ocean is constant but even it

has moods. Sometimes it caresses the shore in a gentle motion. The sandpipers

scurry across the beach; the gulls lift off, fly, land, and do it again. An

occasional pelican patrols beyond the surf looking for a meal. A school of

porpoise sometimes passes; less often a school of pogey fish causes

the surface to flutter. Small sharks feed on the pogey. In a matter of hours,

the ocean can change; sometimes it pounds and pounds and pounds the shore.

Violent breakers make it forbidding. The beach shifts. Wave and wind are

formidable forces.

The Beaches changed in the 1960s; they became a very

different place. Signs of change were there but often went unnoticed in the business of

everyday life. Some were abrupt, some slow and subtle.

The decision not to rebuild the Coaster block was one. It

meant the end of the Boardwalk, the carnival-like midway along the oceanfront

that had entertained so many. The Boardwalk was less and less able to compete

against theme parks. Disneyland set the standard in 1955. In 1958, Walt Disney

decided to build another theme park in central Florida. In 1964-65, the

corporation began buying land south of Orlando and lobbying the Florida state

legislature for special deals. The Florida Turnpike and Interstate Highway

system funneled patrons farther south. The Jacksonville Expressway helped. No

one wanted to turn the Boardwalk into a theme park, its only salvation. The

midway on the sea, smaller, would only continue a few more years.

Dancing on the pier disappeared. People had danced on the

pier to live or recorded music since the 1920s. Many of the rides were for kids.

Dancing and drinking on the pier was for adults but many Fletcher students

danced there as well. Parents staged an all-night dance for those who went to the prom, serving

breakfast at dawn. But it needed repair. When it burned in 1962, there were

those who claimed arson. Maybe so but no one stepped forward to rebuild this

Beaches institution. Instead, a fishing pier went up in a residential area.

Going to the beach meant getting cooler for the breezes

mitigated the summer heat. The wind came ashore in the morning and went to sea

in the afternoon, almost always. Florida gets very hot; the breezes were an

attraction. In the 1960s, those who could afford it air conditioned. In 1965,

for the first time, the majority of automobiles sold in Florida had air

conditioning. People demanded it in businesses and homes as well. The Beaches lost a

competitive advantage.

Air conditioning changed life almost as much as cars. People

stayed inside; youngsters rarely played outside. The sense of community declined. It was hard to know

people you rarely saw and with whom you did not associate. Inside one's air

conditioned car, one lived in isolation, not hearing and feeling the outside.

Watching one of the two commercial television channels meant

not only isolation from others but also being saturated with the cultural values

that big business promulgated to make money. As the decade

marched relentlessly on, TV was in living color, more powerful than black and

white. Unlike the movies, TV taught that one

should buy and buy and buy. Television sets became the idols that people

worshipped, almost always having the prominent place in the home. The commercials were often better than the programs.

They were more important. Commercials promised that article X would bring love,

pain relief, respect, sexual fulfillment, or happiness or some combination

thereof. All one had to do was buy. To get one to watch the commercials, the

programs featured and taught self indulgence and instant gratification, the efficacy of

violence, the supremacy of the U.S., tolerance of divorce and adultery, and that any and all life's problems could be solved in less than half

an hour. Serious, complicated information could be reduced to a sound bite or

two. Television, a big business, created "The Sixties" and was paid

for by other big businesses—General Motors, Proctor & Gamble, Kellogg's, Anheuser-Busch,

RCA, Revlon, Maidenform, Marlboro, Coca-Cola, Holiday Inn—to name a few.1

TV preached consumerism more powerfully than any medium

before could have hoped and encouraged a change in family patterns. TV redefined

what was a "normal" standard of living. TV characters had material

good far out of proportion to what real people made in real life. People did not

stop and say that a private detective would not afford those clothes or that car

or that a woman working in a Mid Western television station would never be able

to afford those clothes or that apartment. Houses were bigger and better

furnished than the average person but the fictional character was portrayed as

average. Who knows how long "Keeping up with the Jones" had existed

but TV blatantly as well as subtlety redefined what the Jones had. Both parents

had to go to work to pay for this new standard of living, a standard that was

constantly escalating.

National brand names replaced local and regional products as television created a national consumer economy.

Expensive, sophisticated, motivational advertising was beyond the financial

means of small businessmen and women. Chain motel chains destroyed the

family-owned motels and hotels, so common on the Beaches. The same happened

to grocery stores, pharmacies, and burger outlets. Such Beaches grocery stores

as the A&A grocery stores were doomed. So, too, was the Surf Maid, the

iconic drive-in restaurant where teens congregated. Discount stores replaced the

5 & 10 cent store and many other shops. The opening of Regency Square Mall in Arlington in

1967 marked the beginning of the end for downtown Jacksonville and for downtown

Jacksonville Beach. Shopping in a mall with its free parking, climate control, wide variety of

stores, and wonderful lighting was easier than paying to park and trudging in

the weather from store to store. So shoppers quit going downtown. The city

centers, both in Jacksonville and in Jacksonville Beach, became hollow.

Baby Boomers, those born from 1946 through 1964, became a

cultural tsunami in the United States, changing commerce, attitudes, and

politics. The first of the generation turned 18 in 1964. Their parents, in

particular, and society, in general, had indulged them, had given them power.

Things were done "for the children" instead of "for the

marriage" or "for society." They and their older siblings had

changed popular music so that reflected their immediate concerns, that is, rock'n'roll.

Advertisers, having figured out that teenagers and young adults, had more

discretionary income than their parents, designed ad campaigns to get them to

buy. Pepsi proclaimed it was the drink of the "Pepsi Generation" and

cut into the market share of Coca-Cola. When boomers began to wear underwear as

a primary article of clothing, often using it to display a slogan or dying

it, that is, the T-Shirt, corporations began the T-Shirt industry. When

the boomers modified panel trucks and the like, Detroit began creating the

passenger van. As the Boomers created a sexual revolution, society loosened its

rules, de facto and de jure, towards sexual practices. When Boomers could not

get their way, they threw tantrums on campuses and in the streets. They saw the

disconnect between what the US said it was and the everyday reality and believed

that they could make things right. And society encouraged them.

Although the Beaches were affected by this social change, the

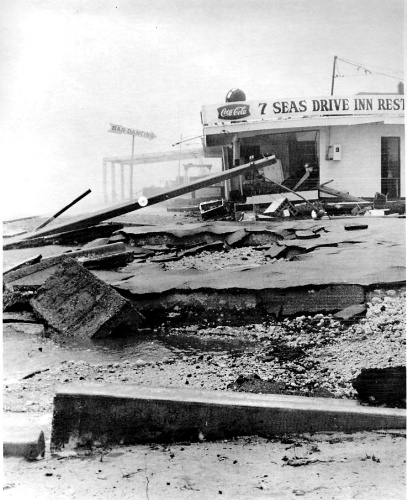

immediate problem in 1964 was Hurricane Dora. On September 10th, it devastated the

Beaches. Both piers, Jacksonville Beach and Atlantic Beach were hit and

destroyed. Damage to the Atlantic Beach Hotel was

extensive. Although owner Gerry Adams, son of W. H. Adams, Sr., rebuilt it, he

sold it in 1969. The hurricane, chain motels, and the growth of tourist

destinations further south made it unprofitable. The Adams family had been on

the hotel business at the Beaches since early in the century. Le Chateau

Restaurant in Atlantic Beach went as well. The Seven Seas Drive-In and other

Boardwalk businesses were damaged. Dora

damaged a number of other businesses as well as home on the Beaches. The Ponte

Vedra Inn and Club was inundated. Dora made some people afraid to live

on the ocean. It caused only one fatality but destroyed $280

million of property, $1,764,000,000 in 2005 terms.2

Figure 6-1 1964 Atlantic Beach Hotel After

Hurricane Dora

Figure 6-2 Atlantic Beach Hotel (photo by Nancy Adams)

Figure 6-3 1964,

Hurricane Dora. Le Chateau Restaurant

Figure 6-4 1964, Hurricane Dora. Le Chateau Restaurant

Figure 6-5 Seven Seas Drive-In Restaurant

Figure 6-7 Jacksonville Beach

Figure 6-8 Seaside homes in Jacksonville Beach

Figure 6-9

1964 Ponte Vedra Inn & Club

For Florida, the Cold War came closer to home. The October 4, 1957

launching of the space satellite Sputnik by the U.S.S.R. sparked a drive

by the United States to surpass their Cold War adversary. Florida benefited by

the creation of the major launch site on Cape Canaveral, renamed Cape Kennedy

after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1962. U.S. government

money spurted into the state. The Jacksonville area Naval bases had been beefed

up by the Korean War in the early 1950s. Fidel Castro and a coalition overthrew the Fulgencio

Batista dictatorship in Cuba. On January 1, 1959, 55 officials and family members connected

to Fulgencio Batista landed in Jacksonville, including three Batista children

and Army chief

of Staff Francisco Tabernilla. Within two years, Castro was clearly establishing

his own dictatorship albeit an anti-capitalist one. The U.S. sponsored the Bay

of Pigs Invasion in 1961; Jacksonville was involved. Cubans who could fled to

Florida, becoming the nation's most prosperous ethnic group and a major force in

Florida politics. When U.S. got more involved in the Vietnamese civil war to the

point that the war became the Vietnam War, Jacksonville was involved. The U.S.

government pumped more and more money into Duval County. The Beaches benefited

because of Mayport. The military also influenced the area with its attitudes and

personnel practices. President Harry Truman had ordered the desegregation of the

armed forces in 1948; although change was slower in the Navy, it occurred. Duval

County, however, was very segregated.

African-Americans had always been an critical component of

Jacksonville's population; they had been a majority in the 1900 and 1910

censuses and a very large minority thereafter. In 1960, they were still 41.1% of the city's population although this

figure is deceptive because many "whites" had moved outside the city

limits. The percentage of African-Americans was not that high at the

Beaches but substantial; besides, what happened in Jacksonville affected the Beaches.

| Year |

Population |

"White" |

% |

"Black" |

% |

| 1900 |

28,429 |

12,158 |

42.8 |

16,236 |

57.1 |

| 1910 |

57,699 |

28,329 |

49.1 |

29,293 |

50.8 |

| 1920 |

91,558 |

49,972 |

54.6 |

41,520 |

45.3 |

| 1930 |

129,540 |

81,322 |

62.8 |

48,196 |

37.2 |

| 1940 |

173,065 |

111,247 |

64.3 |

61,782 |

35.7 |

| 1950 |

204,517 |

131,988 |

64.5 |

72,450 |

35.4 |

| 1960 |

201,030 |

118,286

|

58.8 |

82,525 |

41.1 |

| 19703 |

528,865 |

401,695 |

77.1 |

118,158 |

22.3 |

| 1980 |

540,920 |

394,756 |

73.0 |

137,324 |

25.4 |

| 1990 |

635,230 |

456,529 |

71.9 |

160,283 |

25.1 |

Figure 6-10 City of Jacksonville Population, 1900-1990

Racial discrimination and undemocratic practices became increasingly problematic

since 1941 because the United States had been loudly proclaiming its belief in

democracy and its opposition to racism. WWII was fought, in part, against German

and Japanese racism as well as against totalitarianism. After the war, the U.S.

adopted Harry Truman's Containment

Policy against the Soviet Bloc, deciding to stop the expansionism of

Communists countries until their internal contradictions destroyed them from

within. It was a long-haul policy. The United States argued that liberal

democracy produced human happiness, freedom, and wealth whereas Communism

produced misery. Much of the Cold War and some hot wars were "fought"

in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, areas where people's skin color tended to be

darker than "whites" in the United States. American minorities—African-Americans,

Mexican-Americans, American Indians, etc.—saw the contradiction between

propaganda and reality and challenged the status quo.

Jacksonville had long been a racist city; the near equal number of

"whites" and "blacks" made "whites" fearful that

their privileges might end. The Ku Klux Klan had been a force in the 1920s and

it had not disappeared. Few "whites" were in the Klan but they resisted

desegregation. When Rutledge Pearson led demonstrations in August ,1960

against segregated lunch counters at the downtown Woolworth's, McCrorys, and

Kress stores. One day, two "black" youths accidentally knocked a

"white" woman into a plate glass window. Then on another day two women

got into a fight. On August 27th, hundreds of Klansmen and other bigots

demonstrated in downtown Jacksonville with the police watching. When some young

"blacks" tried to get lunch counter service at the Grant's store and

were refused, they were attacked by the "white" demonstrators who used ax handles and other weapons. They chased

the teenagers into a

"black" section of town but were run out by a "black" gang. Police

intervention stopped the riot. More "blacks" than "whites"

were arrested, of course. The city government of Haydon Burns, even though

African-American votes put him in office, was racist. He was a powerful force in

Jacksonville affairs as mayor from 1949-1965, when he became governor. Burns was

a segregationist so he refused to create a biracial commission to resolve the

issues. He was a determined conservative mayor of a conservative city.

African-Americans threatened an economic boycott and "white"

businessmen, fearing loss of profits, agreed to meet with African-American

leaders and work out compromises. Desegregation began. "Green" was a

more powerful color than "white" and "black."

Peace lasted a few years when it became clear that what

little desegregation that had occurred was nothing more than a token. Pressure

to change increased. A boycott was suggested and protests. Some

"whites" threatened violence. Then, on February, 16, 1964, a bomb

exploded in the home of Iona Godfrey, a civil rights worker whose son had

integrated a "white" school. No one was hurt but the incident meant

that the civil discourse ceased to exist. The NAACP stepped up demonstrations

and effort to integrate businesses. Tensions increased. Then, on March 23, 1964,

riots broke out and lasted until calm was restored on March 25th. Even Burns,

who was running for governor, finally had to admit that the two sides needed to

talk and make accomodations.4 Desegregation

of businesses, some schools, and some employment ensued. That Dr. Martin Luther King,

Jr. led demonstrations that year in St. Augustine, thirty-miles away, encouraged

people in Jacksonville to find solutions.

Jacksonville found a solution to bad government as well, a

solution that would transform Duval County, including the Beaches. Burns had

been an effective mayor in many respects. He cleaned up downtown and the

riverfront. He told "The Jacksonville Story," an effort to

attract major corporations to the city and succeeded. “Later, when state law created a favorable

environment for insurance companies, Jacksonville’s skyline became dominated by

insurance-company logos: Prudential, Gulf Life, Independent Life and American

Heritage Life.”5

The Burns administration developed a reputation for corruption. His police department was scandalous. Grand juries began indicting many public officials.

"Some thought that electing Burns governor was a great way to get him out of

town.”6

Then the Duval County schools lost their accreditation from

the Southern Association of Schools and Colleges in 1965, a major embarrassment.

That was the fault of a different government and its elected superintendent, Ish

Brant, former football coach, athletic director and assistant principal at

Fletcher Junior-Senior High School, and local leaders. The accrediting association tried this

desperate measure because Duval County and

community leaders persisted in trying to educate on the cheap. Funds were so

lacking that schools had not been cleaned in years; current textbooks were in

short supply; and the instructional staff was demoralized by low pay and

mediocre to bad working conditions. African-Americans students and teachers

were the proverbial "red-headed stepchildren" of the system. They got

what, if anything, was left over.

Community leaders acted but it took a few years to effect the

consolidation of Jacksonville and Duval Country in 1967-68. Support for the

change came

from a variety of sources. Brant used the loss of school accreditation to

get the funding he had long sought. One television station did the nightly news with a

reporter standing in front of the city hall skyscraper telling of the latest

city employee to get indicted. Someone devised a very clever way to show the

governmental problems in the county, problems that facilitated confusion and

corruption. The host of the TV program stood in a bare room with an outline map

of the country on the floor. Each time he mentioned a government that existed in

the county, he put a stanchion with the name of the entity on the map. By the

time the program ended, he had to stand outside the map because there was no

room. Voters got the point. The system in Duval County was rotten. In August, 1967,

the voters of Jacksonville and Duval County decided, with 65 percent of the votes cast,

to consolidate the county and the city. Baldwin to the west and Atlantic,

Neptune, and Jacksonville Beaches refused, however. On October 1, 1968,

Jacksonville marched out to Pablo Creek. The Beaches were never the same. They

were dwarfed by a government covering 840 square miles, the largest city in land

area in the world.7

The Beaches, whether the residents liked it or not, had

become a bedroom community of Jacksonville. Maintaining independence from

Jacksonville was a constant battle. Interlocal agreements between the county

(Jacksonville) and the Beaches governments had to be negotiated again and again;

imperial Jacksonville wanted control. Deciding the boundaries lines between

would, inevitably, be a constant problem even when the Beaches governments won

in the Florida Supreme Court. As the land along Atlantic and Beach Boulevards

was filled with homes and businesses, cross roads running north and south had to

be expanded or built. The J. Turner Butler Boulevard, an expressway opened in

1997, ran across the southern part of Jacksonville. Dubbed by wags as the

"road to nowhere" it soon fostered development along its route and in

south Jacksonville Beach and in Ponte Vedra Beach. It reinforced the fact that

the Beaches were Jacksonville, whether they liked it or not.

The Beaches population grew and grew.

In 1964, Duncan U. Fletcher Junior-Senior High School split. The high school

moved across the street into Neptune Beach and the former school became a

"middle school." The unity of the Beaches was broken. The population

growth in northern St. Johns River county, in Ponte Vedra Beach and Palm

Valley especially, meant the creation of Nease High School. Private high schools

further fragmented the Beaches. They had become simply part of the urban sprawl.

They went from tents on the beach to a congested conglomeration of chain stores,

expensive houses and condos, and modest dwelling. The last will go; greed,

conspicuous consumption. and egotism will conquer the traditionalists, the ones

who try to hold onto the past. The Beaches had lost their raison d'etre. Driving

on the beach was outlawed in 1979, killing a tradition that had existed since

1906. The seawalls or bulkheads were buried under new sand.

Figure

6-11 The Boardwalk, 2004

Only the ocean and its beach were constant. Upon reflection, the city on the St.

Johns River had won; it swallowed the Beaches.

Figure 6-12 Fuller Warren Bridge, Jacksonville

__________

1. See Bob Garfield, " Top 100 Advertising Campaigns of the Century;

Randall Rothenberg, "The Advertising Century," gives a quick overview of the power of

television advertising.

2.Cost-of-Living Calculator - AIER.

3. Jacksonville and Duval County became synonymous in 1968 and all the “white” suburbs became part of the city.

4. Abel A. Bartley, "The 1960 and 1964 Jacksonville Riots: How Struggle Led

to Progress," Florida Historical Quarterly 78:1, Summer 1999, pp. 46-73.

Barley asserts that Pearson, an outstanding athlete, had been signed to play for

the Jacksonville Beach Sea Birds but the ballpark was closed to prevent his

playing.

5.. City of Jacksonville Web site.

6. Bill Foley, The Jacksonville

Story,” February 21, 1999.

7. James

B. Crooks, Jacksonville: The Consolidation Story, From Civil Rights to the Jaguars. 2004., p. 150. See also Richard

A. Martin, A Quiet Revolution: The Consolidation of Jacksonville-Duval County and the

Dynamics of Urban Political Reform. 1993. James B. Crooks, "An

Introduction to the History of Jacksonville Race Relations," Address

given to the JCCI Improving Race Relations study committee, October 30, 2001.

<< 5: After WWII || Bibliography and Sources