|

2: The Migrant Circumstances

<< 1: Introduction || 3: Nineteen Migrant Families >>

THE MIGRANT CIRCUMSTANCES

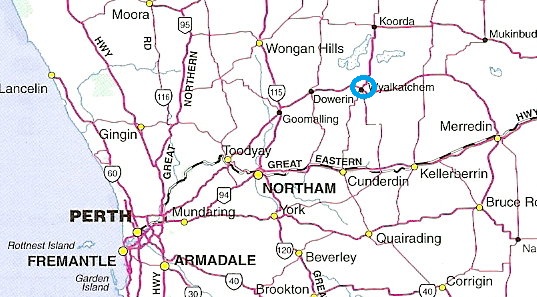

This chapter deals with the general circumstances of the post-war migrants to Wyalkatchem and how they arrived from Europe. The following chapter examines specific migrant families.

Source: West Moto Park

Wyalkatchem's Compact Migrant Tent "Colony"--The "Kemp"

Most of Wyalkatchem's initial post-war group of

newcomers reached the town during the latter months of 1950 or during early

1951, with the majority, until late 1952 or even early 1953, living in tents

south of the railway line and just west of the railway barracks complex which

was situated directly south of the western end of the railway station. In other

words, the newcomers initially lived on a specially designated tract of public

bushland away from the township. This precinct lay within what is best

described as the north-eastern corner of the intersection of the

Dowerin-Korrelocking and the Wyalkatchem-Cunderdin roads. The initial group of

migrants had all reached the town by train since Wyalkatchem still had regular

passenger rail services from Perth and Northam. In Northam they had generally

been housed for up to about six months at a former Army Camp on the

Perth-Northam road several kilometres west of Northam or the Holden Immigration

Accommodation Centre, a wartime Army hospital and recovery establishment – the

118th Army General Hospital - for soldiers wounded in the Pacific

Theatre or what was then often referred to throughout Australia simply as “The

Islands”, and specialised in caring for servicemen who had suffered serious

battle burns. The Holden Centre was located just north of Northam town site and

within that town's boundaries.

Camp or communal life was not unfamiliar to

these people as all had been living in this manner since shortly after the end

of hostilities in Europe in May 1945, so for well over five years. Some had

even endured communal life for all or most of the war either as prisoners-of-war

or forced labourers in the Reich. The

one Polish family, the Kozlowskis, which consisted of a widow, a son and

daughter, who never lived within Wyalkatchem's railway camp but instead within

the town precinct, had reached Australia either via Soviet Siberia or

Kazakhstan and British East Africa where they had lived in a camp on the shores

of Lake Victoria, Uganda, called Koja.[1]

All those who, unlike the Kozlowskis, reached WA via Hitler's Third Reich, not Stalin's Siberia or

Kazakhstan and British East Africa, had, before the end of the war, lived in

various forms of abode, from communal barracks linked to large German

industrial establishments to single rooms on German farmlets, or in

prisoner-of-war camps. In the case of Helena Poprzeczna, she had spent nearly

two years in a sub-camp of the major Silesian-based concentration camp and SS

killing centre, Auschwitz-Birkenau or Auschwitz II, called Babice. [2]

Another feature of the Eastern Europeans was that to a man and woman they had

not lived in their family home since the early 1940s, so for about a decade

before reaching Wyalkatchem. All had been on the move so were transients all

that time.

Wyalkachem's Polish migrants invariably

described the camp as “kemp”. There was no “the” used before the word “kemp”

because the Polish language is without the definite article. Whenever a Pole

was therefore asked where he or she lived they would say, “W [pronounced “V”

and meaning, “in”, or, “within”] kempie”, or, if an attempt was made to sound

Australian, then, “In de kemp”, or even, “In de rul-vay [railway] kemp”. The

English language was therefore being adapted, or more correctly, Polonized, in

exactly the same way that it had been before and contemporaneously in England,

Canada and the United States where Poles had also settled before and after

1945.

For the years 1951-53 the “kemp” area was a

relatively compact, but not congested, tent settlement with each family having

been initially allocated by the Western Australian Government Railways (WAGR) -

one of the State's then biggest employers not only of migrants but also of

Australians - two bright white canvas tents that measured about five by three

metres. The entrances of both these issued tents faced each other and they

stood about four metres apart. Soon after each of the dual tent “residences”

had been allocated to the newly-arrived families a three-walled corrugated iron

kitchen, with the open side facing the gap between or facing both tents,

thereby enclosing the third side was built.

The WAGR-issued tents had another feature that

helped ensure they were virtually waterproof, and that was an additional or

separate sheet of white canvas that was tightly stretched about a third of a

metre above the tents canvas roof's sheeting. This meant that the tents had two

roofing sheets, a design that meant very little, if any, water penetrated a

tent even on particularly gusty and rainy days and nights.

The migrant camp covered about two to three

hectares of recently cleared scrub country, bush, and at its peak, from late

1950 until early 1953, had about a dozen families living within its unspecified

boundaries. There was no perimeter fence or some such barrier, a major

difference to what most “kemp” residence had experienced in Reich-controlled Europe. After about

1952-53 the number of tent residences, and thus dwellers, steadily dwindled to

generally be taken up by single men, sometimes even Australian single men, with

only three or so families remaining in the “kemp” until about 1958. What

happened to most of the original “kemp” dwellers was that the WAGR had

initiated a program of progressively relocating families to WAGR or

government-owned houses within the town site, generally to Flint Street,

especially at its western end, just east of the late Norman Eaton's farm or

homestead paddock. Others were located on Railway Terrace, at its western end,

opposite what was then Mosel's Garage. Notwithstanding this drift into the town

site as the 1950s unfolded a handful of families remained in the “kemp”. In

these cases, however, the tents were steadily replaced by WAGR-issued jarrah

cabins, which were about the size of an average sealed WAGR railway carriage.

Such cabins had a window at one end and a door at the other and a corrugated

iron roof, sometimes triangular others a semi-circle. So, instead of living in

two tents facing each other two larger cabins replaced originally issued tents.

In these cases the corrugated iron kitchen continued to be standard residential

issue. Even in late 2005, well over half a century after having left the

“kemp”, the author can clearly visualize most of it and can still vividly

picture the interior of both his family's tents and their corrugated iron

kitchen and tarpaulin, metal and timber-covered ante “room”.

One of the Poprzeczny tents was used

solely as sleeping quarters, which had a parental and a child's bed and briefly

a cot. Both beds were built by Jozef Poprzeczny from scrounged timber while the

mattresses had been brought from Trier, which is situated on the banks of the

Moselle River in the then French-occupied Zone of West Germany where the family

had lived until late 1949, the year they left by train for Naples via western

Austria. [3]

The second or adjacent tent was used for general storage purposes and also as

the room in which he carried out some tailoring since he had been trained in

this craft in pre-war Poland.

None of the

“kemp's” combination tent and corrugated iron structures had access to running

water. Basins, buckets, and tubs therefore tended to dominate spare corners;

generally resting on homemade stools that had been built from scrounged jarrah

or pinewood from beer boxes which were in abundance at the hotel. However, each

family was fairly quickly allocated a corrugated out-house or toilet, which,

like the rest of the town, was on the weekly night-soil service. Water from the

Railway Dam that was situated about 1.5-kilometres east of the town alongside

the Korrelocking road, was obtained from a single communal tap located roughly

in the middle of the “kemp”. Not far from the tap was a communal washroom,

which had a large brick fireplace, in the middle of which sat a large copper

basin, so was called the copper, or, in Polish, “koper”. This was where all

families washed most of their laundry. Nearby were several communal wire cloths

lines, though, as time passed, families tended to erect their own cloths lines

near their tents. Near the communal weatherboard washroom a collective garden

was quickly established and most of the “kemp's” dwellers informally acquired small

patches of ground within what was probably slightly less than a quarter acre

lot to grow vegetables, i.e. cabbages, tomatoes, lettuces and cucumbers.

Watering was done by bucket from the communal tap so children became involved

in this family venture, especially after school. Vegetable productivity was

boosted by use of sheep and cattle manure that was always readily available

since Wyalkatchem's stockyards were situated just south of the “kemp”,

alongside or nearby the Dowerin-to-Trayning road. These yards were well endowed

with sheep and cattle dung because stock auctions were held regularly and

often. If manure was ever in short supply then it could be easily obtained by

going to the station shunting yards when a train load of sheep passed through on

its way to Midland Sale Yards. Since such trains often spent at least an hour

or so in the station's yard manure could be quickly bagged by raking it from

below the spaced flooring upon which the sheep stood.

Although

one could debate the pros and cons of “kemp” life, a question worth asking is

whether it was satisfactory or otherwise to its inhabitants. In seeking to

answer this question it is important to keep several crucial considerations in

mind if one opts to take an overly critical stance. Firstly, WA in 1950 was

barely out of its own period of so-called post-war reconstruction, one in

which rationing and shortages were prevalent. Post-war reconstruction was

essentially a socialist path adopted by the Curtin Government (1942-45) and

implemented by the successor Chifley Government (1945-49) to development that

was guided by the Australian Labor Party whose planks at this time had

originated from the early 1920s, that is, from the immediate post-Great War

Years. [4] Added to this was the fact that both the war

and the post-war reconstruction years of 1945-1949 came hard on the heels of

the Great Depression, meaning life in WA's wheatbelt towns was far from modern

even by the early 1950s. The WA economy of the early 1950s differed markedly

from the State's economy even of the early 1960s, and more so as the latter

decades of the 20th century unfolded. In light

of this it's fair to say life in the “kemp” definitely had certain obvious

strictures – no electricity and no running water being the two most obvious.

But there were other less obvious advantages. First and foremost, the new

arrivals were truly free people, something many today tend to either forget,

so easily overlook, or take for granted without thought. Furthermore, and most

importantly, there was a feeling that one could now get on with one's life, to

raise one's children and to expect to experience material progress, which

happened in all cases. Salaries were low, true, but remuneration rose in real

terms as the 1950s unfolded and people, after their initial two years work for

the WAGR, were free to move elsewhere - both in Australia or overseas, which

all did as the 1950s and 1960s unfolded - to improve their lot if they so

desired. Not often realized by Australians at this time and even to the

present is that all of Australia's immediate post-war migrants had come to

this country on condition they worked wherever sent. If this condition for

migration assistance – payment of passage and full board and keep until

reaching Australia and during one's time in a transit camps – had not applied

it is most unlikely that those who reached Wyalkatchem would ever have settled

there. And finally, it is important to note that even though life in the

“kemp” can be seen as having been communal this point should not be

overstressed since each family had its own dual tent and kitchen complex,

meaning privacy. In other words individual family life had commenced becoming

a part of the new arrivals' way of life in a way that had not been possible in

wartime and post-war camp life in occupied Germany and/or Austria. Underlaying

all this was an assumption that one was, if not yet a naturalized Australia,

then at last on the road to becoming an Australian. Indeed, migrants were

officially designated as New Australians, meaning they were seen as

Australians – though new ones - from the outset. Though it should be added

that in the case of adult Poles gaining command of the English language proved

to be quite a formidable task. Most, if not all, of Wyalkatchem's Polish

families took Australian citizenship either in the 1960s, or soon after.

It should be noted that

Wyalkatchem was not the only wheatbelt town to have a canvas “kemp” on its

outskirts. The early 1950s saw such similar settlements arising in many of the

State's regional townships. Tent camps had earlier been an integral part of

the entire European settlement phase of WA's history, especially in the

Goldfields as well as early timber or logging settlements of the South-West.

It's also worth stressing here the fact that the year 1950 was only 45-years

after Lindsay, Jones and Smith had reached the Wyalkatchem area and both men

and those who took up land in the dozen or so years after they'd arrived lived

in comparable if not far worse conditions. In other words, many of

Wyalkatchem's farmers were the offspring of pioneers who had endured similar

living conditions - no electricity, no running water, no refrigerators and

none of the other accoutrements of modern day, that is, later 20th century, living.

Before further considering the life and times of the

town's post-war newcomers it's worth highlighting the fact that Wyalkatchem's

largely Polish migrant community was not the town's Anglo-Celtic Australians'

first ongoing encounters with continental Europeans.

Wyalkatchem's Post-War Migrants in Historical Context

A major problem historians who

focus upon civilian demographic aspects of World War II encounter is the wide

variance in statistical estimates of people involved. Because of this the

figures quoted by many writers should be regarded only as guesstimates, that

is, as being only roughly in the order suggested unless specific and reliable

sources are cited. With this warning in mind it is generally agreed, however,

that the German or Reich war economy of 1940-45,

through varying methods, resettled or transferred forcibly or otherwise, in

the order of eight million non-Germans into the Reich (Germany and Austria) to work in various tasks

to assist in the Hitler war efforts. After the war, so after May 1945, some

six to seven million of these steadily returned to their homelands with most

of these having left the conquered Reich by about

1947-48. In addition to these there were several tens of thousands of allied

prisoners-of-war who were released and treated according to special purpose

military protocols.

The single

overriding factor that resulted in the remaining one to two million people who

remained in the defeated Reich was their refusal to

return to their homelands since the Red Army had penetrated as far as central

Germany liberating from Nazism East-Central Europe; the three Baltic States of

Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, Poland, most of Czechoslovakia, Hungary and

Bulgaria and Rumania. In addition some people from lands inside the Soviet

Union, Ukraine and Belarus especially, also found themselves in the Reich. Most of these also did not desire to return to

the Stalinist USSR. Although it is fair and accurate to describe this deep

westward penetration by the Red Army as liberation, since the ultimate Nazi

aim was to expel all Slavs and most Balts into Western Siberia under the term

of Hitler's top secret Generalplan Ost,

Soviet-style liberation differed markedly from the liberation from the West

that came with the entry of American, British and other, including Polish,

forces. The up to two million Displaced Persons in occupied Germany after 1945

did not see the Red or Bolshevik form of liberation of their homelands as

being to their desires since it had meant the imposition of a single party or

totalitarian order. Furthermore, Stalin's USSR and Poland were capable of

treating those returning from the West in a quite harsh manner.

The upshot of the two figures -

the eight million people forcibly or otherwise allocated by German, including

SS, manpower and demographic agencies to work in the wartime Reich and between one and two million who remained

after about 1947-48 is that there were well over a million so-called Displaced

Persons who refused to return to their homes. And it is from this pool of

between one and two million people that Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada,

the United States and even some South American countries drew varying numbers

of immigrants during the late 1940s to early 1950s.

The repatriation of eight million

displaced persons to their homelands in the post-war years was carried out

through the joint co-operation of the United National Relief and

Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the Allied forces of occupation. For

the purpose of caring for and ultimately re-settling over one million

displaced persons who did not want to return to their homelands, the United

Nations created the International Refugee Organization (IRO). The assembling

of these persons into camps and the housing, clothing and feeding of them was

the primary consideration of the IRO. It was the organization's ultimate aim

to have these persons re-settled in Europe and other parts of the world.

Consular representatives of countries desirous of accepting them as immigrants

were located in the IRO camps and displaced persons approached the

representatives of the country to which they desired to emigrate. If it was a

country outside Europe they were transported to a port of embarkation and

awaited shipment to that country. [5]

It should be noted that the Displaced Persons scheme,

which was responsible for all the non-Dutch migrants who settled in

Wyalkatchem after September 1950, ran alongside other assisted arrival schemes

as well as the intake of full fair paying arrivals. Not to be overlooked is

the fact that Australia throughout its entire history – so since and during

its convict era – has approach the question of immigrants in a utilitarian

manner, that is, it has only sought to attract people with skills that were in

need during particular periods.

The Eastern Europeans who reached Wyalkatchem were often

unskilled workers. But nevertheless they were accepted since that's what the

WAGR, various water supply authorities and Co-operative Bulk Handling (CBH) at

the time required. Such a statement does not, of course, overlook the

humanitarian motive in the acceptance of these people, nor does it ignore the

fact that even in the early 21st century

Australia continues to have a relatively sizeable humanitarian component

within its annual migrant intake. What is being stressed, however, is the fact

that migration has tended to reflect or been moulded around the needs of the

national, as well as individual state, labour markets, that is, it was and

remains essentially utilitarian.

Australia's post-war non-British migrant intake was to be

100,000 people and of this WA took about 19,000 with more than half from

Poland. The author of one of the best standard texts on the ships that brought

this component to Australia, Peter Plowman, says:

It was during 1944 that the Australian Government began

looking towards post-war migration, and in 1945 established the first

Department of Immigration. Late that year, a Commonwealth Immigration Advisory

Committee made a tour of Europe, seeking suitable migrants, and suggested that

people be accepted from many European countries as well as Britain. [6]

Earlier Plowman pointed out that the Great Depression of

the 1930s had resulted in the virtual cessation of a migrant intake by

Australia. The year that the war broke, 1939, saw just 3000 British migrants

reaching Australia's shores. In that year also Australia agreed to accept some

15,000 political refugees, mostly Jews, from Germany and Austria, the Reich. Of this proposed intake, however, only 7000

arrived. The major Nazi figure behind these expulsions was the infamous SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer

Adolf Eichmann, who faced trial in Israel in 1962 and was executed for his

subsequent involvement in Aktion Reinhardt,

Hitler's and Heinrich Himmler's top secret program to exterminate all

European Jews. Aktion Reinhardt was headed by SS-Brigadefuhrer Odilo Globocnik, who, during 1938-39,

was Gauleiter of Vienna. The Austrian capital had a

sizeable Jewish population that was largely expelled from that city and other

parts of Austria by Eichmann before the outbreak of war in September 1939. [7] Globocnik was based in the south-eastern Polish

city of Lublin between November 1939 and September 1943. Ten months before he

was transferred to Trieste he launched an ethnic cleansing action and settled

Volksdeutsche in the villages and homes of the

expelled ethnic Polish peasant farmers, with one of those affected by this

being Helena Poprzeczna, who was expelled from her village of Skierbieszow by

Globocnik's German/Austrian and Ukrainian policing units. This action was, in

fact, the launching of little-known Generalplan

Ost, the other major Himmler demographic program that envisaged the

Germanization of all Slavic lands between Berlin and the Ural Mountain range.

This plan was in fact the reason Hitler went to war against Stalin's Soviet

Union after their initial short-termed friendship of 1939-41, to gain

so-called Lebensraum (living room). Under Generalplan Ost all Slavs – Poles, Czechs, Slovaks,

Ukrainians, Belarusans and Ukrainians – as well as most Balts – Estonians,

Latvians and Lithuanians – would be expelled over a 25-years period into

Western Siberia, so to the lands on the eastern side of the Ural Mountain

chain. And Germans, including Volksdeutsche, would

be settled upon the vacated lands.

March 1946, so less than a year after the war had ended,

was to see the signing of an agreement with the British Government for Britons

to emigrate to Australia.

The

first departure under the new agreement was taken by Ormonde from Tilbury on

10 October 1947, with 1052 migrants. [8]

According to Plowman, the next major milestone came in

July 1947 when the Australian Government entered an agreement with the

International Refugee Organization (IRO) in Geneva to take some 12,000

displaced persons annually out of Europe. This quite sizeable target was to be

subsequently boosted. It should be noted that similar programs were being

contemporaneously launched by the United States, Canada and New Zealand. One

outcome of this concurrent running of migration programs meant a sudden demand

for shipping was felt by the international maritime sector.

The first of these vessels to come

to Australia was the American troopship, General Stuart

Heintzelmann, which departed Bremerhaven 1 November 1947 with 843 Balts on

board, and arrived in Fremantle on 28 November. [9]

It was the arrival of these early

Balts that appears to have led many Western Australians to regard all DPs, as

“Balts”. Australia in that year had a population of about 7.5 million people,

of which 98 per cent were of Anglo-Celtic descent. According to Plowman, by

1961, so less than 15-years later, Australia's population had risen to 10.5

million, an increase of three million or nearly half Australia's pre-1945

population, with about a quarter of this increase being people of non-British

descent. It's worth keeping these aggregate figures and proportions in mind

when considering Wyalkatchem's tiny intake of non Anglo-Celtic migrants after

September 1950, so when the railway camp commenced accepting the first

families whose breadwinners had been dispatched to the town to become railway

repair workers. And it should be noted that what Wyalkatchem experienced in

this regard was repeated across many central wheatbelt towns as well as in

WA's major regional towns like Northam, Albany and Bunbury, as well as in the

Perth-Fremantle area. Also noteworthy is the fact that after 1950, the

metropolitan area began to demographically outstrip the agricultural region as

it had, after about 1910, the Goldfields. Prior to 1910 the Goldfields had

demographically challenged the Perth-Fremantle area, so significant was the

impact of the gold rushes that began in the early 1890s, just after Western

Australia gained self-government from London.

Easily forgotten is the fact that

Wyalkatchem's “Refos”, or New Australians, most of whom briefly inhabited the

camp between 1950 and about 1953, were not the town's or the shire's first

non-Anglo-Celtic or non-English speaking European newcomers. Wyalkatchem's

dozen or so post-war East European refugee families were in fact preceded in

the mid-1940s by Italian prisoners-of-war (PWs), who were officially referred

to as PW (I)s. German PWs, who were also transported to WA, but not to farming

centres like Wyalkatchem, were consequently referred to as PW(G)s. Austrians

who made up a not insignificant portion of the German Army, the Wehrmacht, were classified simply as Germans. And

Italians who were known to be fascists or ardent Mussolini backers were each

designated PW(IX); meaning political allegiance was not overlooked or ignored

by Australia's military authorities.

Both Axis PWs had, in the main, been captured in North

Africa, either by British, Australia, New Zealand, or perhaps even by Polish

troops, who, after 1941, saw service in Egypt and Libya, especially. As a rule

the captured Germans and Austrians had been members of General Erwin Rommel's

Afrika Korp. Despite

this there was a smattering of German airmen and merchant marine personnel who

had been captured elsewhere, including in the Persian Gulf area in the case of

the latter.

Unlike the Eastern Europeans, all of the

hundred or so PW(I)s who reached Wyalkatchem District after 1943 lived on

outlying farms and were employed as farm hands whereas the subsequent “Refos”

were generally employed by the WAGR as fetlock workers, also called navvies or

even gangers, with some employed by CBH and later the Country Scheme Water

Board, a northward and central wheatbelt extension of the much earlier

Goldfields water provision program.

The North African Campaign resulted in some 17,200 Italian

PWs being dispatched to Australia. Australia turned towards becoming a PW

detention venue after prisoner-of-war camps in Egypt and other parts of North

Africa, as well as East Africa and India, had been filled. In other words,

because of ongoing Allied military successes. Continental USA was also used as

a venue for German/Austrian as well as Italian captives, with many tens of

thousands being held there. The steady filling-up of the behind-the-front

African and Indian camps, which gathered even greater pace after the Battle of

El Alamein (October/November 1942) – the decisive turning points of the North

Africa Campaign meant that the transfer of PWs to Australia came to be seen as

offering two advantages – firstly, removal of captured military personnel to a

distant and virtually impossible location to escape from, and secondly, as a

source of desperately needed farm labour, the role the Italians were to fill

quite well. Allied economies, like those of the Third Reich, needed to replace manpower that had been drawn

to various fighting fronts. Although a number of PWs escaped from camps around

Australia none ever managed to leave the country simply because Australia was

so far from Italy and the Reich. PW(I)s held in WA were earmarked for farm

work while PW(G)s were employed as timber cutters since wood was still a

significant fuel, especially in public hospitals, to generate steam, and for

domestic cooking and heating as well as by the WAGR at railway stations and in

workers' barracks.

The Germans

were always held at Marrinup and were employed on the cutting of firewood in

the surrounding forests. By 1945 over 60 per cent of this wood came to Perth

as fuel for home heating, hospital and army use.[10]

A small number of PW(I)s were also

employed in non-agricultural occupations such as repairing the Trans-Australia

railway on the Nullarbor Plain, meaning they left the deserts of North Africa

to labour on similar harsh terrain in Australia. In this regard those

allocated to towns like Wyalkatchem were climatically speaking far better off.

[11]

Of the 17,200 Italian PW transferred to Australia nearly

3500 or some 20 per cent were directed to WA. Most were initially dispatched

to a camp near Dwellingup, south of Perth, called Marrinup. However, as the

war continued PW(I)s were increasingly detained in a smaller holding compound

at Karrakatta which was designated Number 8 Prisoner-of-War Labour Detachment

from No. 13 Camp, Murchison, Victoria, and dispatched to farms in the

wheatbelt. In the latter stages of the war another smaller transit compound

became operational in Moora and used to distribute PW(I)s across the State's

northern wheatbelt districts.

From Marrinup, Karrakatta, and later, the town of Moora,

the PW(I)s were placed under the local jurisdiction of so-called

Prisoner-of-War Control Centres (PWCC), which were located in larger wheatbelt

towns. Wyalkatchem had such a PWCC. From these PWCCs PW(I)s were individually

disbursed to surrounding farms, meaning they were hired out at one pound per

week as farmhands.

The

Italians were mostly employed in threes or pairs on farms in the South-West,

the Central or the Northern wheatbelts of WA with the farmer paying the

Australian Government one pound per week for their labour. The farmer was

responsible for the feeding of the prisoners, and the farms were inspected

once a fortnight by the Australian Army local Prisoner Control Centres. [12]

According to Perth historical researcher, Ernest Polis,

Wyalkatchem's PWCC commenced operating on 19 April 1944, so about a year

before the war in Europe ended, and it had an initial strength of 100 PW(I)s

to administer. Administration included payment for work, provision of prisoner

attire and overseeing their proper treatment by farmers. Wyalkatchem's PWCC

ceased operations 13 months later, in May 1946, when all its PW(I)s were

transferred 100-kilometres westwards to the Northam Army Camp for eventual

repatriation to Italy which was to commence by September 1946, so just four

years before the first Eastern Europeans began arriving in the town and the

erection of the railway camp.

When the repatriation of prisoners commenced in August

1946 they were assembled in Marrinup for processing before being shipped from

Fremantle to Genoa or Naples in Italy. The Marrinup Camp closed in September

1946 and POW activities transferred to Northam Army Camp where No. 4 POW

Compound was established. All but a few POWs had left WA by December 1946. [13]

Wyalkatchem District's historian, John C. Rice, dates the

PWCC's closure at March but adds the proviso that some of its PW(I)s were

still being employed after that date, which explains the difference.

The POW Centre in Wyalkatchem

closed in March 1946. Some prisoners were still working on farms in the

district, but they were being brought in to the Northam Army Camp and there

would be no more of them in the Eastern Districts after the end of May. [14]

For most of the time the Wyalkatchem PWCC was commanded by

a Captain Harold Tindale Coppock (WX3404) who was then aged 32-years. The

Wyalkatchem Centre was officially designated W16 as part of the war

establishment of the state's line of communication and was one of 28 such

precincts within the state. [15]

According to University of

Victoria historian, Anthony Cappello:

Eventually the PWs returned to Italy, beginning in August

1945. Out of the 17,131 Italian PWs in Australia, eighteen committed suicide,

one was shot by a guard and 116 died of natural causes. . . The Italian PWs

had brought manpower to Australia's home front. Some

writers argue that the pro-migration policies, which followed the war got

their inspiration from the example of the Italian PWs. [Emphasis added] [16]

Of these 116 PW(I) natural deaths, 22 of these in Western

Australia, with one of these, a 35-year-old Private Felice Marasco

(PWI-63204), who died in the Wyalkatchem District. He lost his life in an

accident on 7 September 1945 at a Benjaberring

farm, exactly four months after the cessation of hostilities in Europe.

Private Marasco, a member of the 1st Compagnia

Radio, was killed by falling off a tractor into the scarifier that he was

towing. He was to be buried within Wyalkatchem Cemetery's Roman Catholic

section, in grave number 14. Private Marasco had been captured at Amba Alagi,

Abyssinia, on 19 May 1941 where the Italians had unexpectedly surrendered

three days earlier to the Indian “Ball of Fire” Division. He arrived in WA in

February 1944, having being interned in British India since 17 October 1941.

In civilian life he had been a clerk and was born in Nocera Terenise in the

Catanzaro area of Calabria, southern Italy. [17]

According to Polis, a general

order was issued by the Australian Government in the mid-1950s for the

exhumation of bodies of Axis servicemen so that the remains of the more than

100 deceased PW(I)s could be re-buried in a single cemetery where they would

be more easily overseen in accordance with treaty arrangements and obligations

that also affected Australians buried beyond Australia's shores. Although

Marasco's remains should therefore have been treated in accordance with that

general order this appears not to have happened in his case, probably due to a

bureaucractic oversight which means that Wyalkatchem's Cemetery has the unique

distinction of continuing to be the resting place of a World War II Italian

PW.

Little has been published

by Western Australians who employed PW(I)'s. Fortunately Wyalkatchem farmer,

military historian and author, Paul de Pierres, has not overlooked this

episode in the history of his family farm, named Derdebin. He has highlighted

this forgotten minor chapter of the district's past in his self-published

history of his French ancestors, which highlights the achievements of his

pioneering grandfather, Vicomte Guy de Pierres (1880-1954), who settled

south-east of Wyalkatchem after 1912, following nearly a decade of sheep

grazing on the eastern shore of South Australia's Lake Eyre.

Derdebin was allotted three

Italian Prisoners of War named Giovanni, Francesco and Andre, to help with the

work and they were billeted at the original farmhouse where they cooked and

looked after themselves. . . The POWs were peasant farmers in Italy and really

not much use for anything but basic labouring around the farm. One of them,

Francesco, was not happy and was replaced by another named Joseppe. [18]

The wartime Wyalkatchem or Derdebin farming experience

must not have been that unpleasant for at least one of these, since he gave

serious consideration to returning to WA as a free migrant from Italy after

having been repatriated after war's end.

. . . Guy [de Pierres] received a letter from their [Guy's

and his wife's] former Italian Prisoner of War, Giovanni di Fabio, asking if

he could return to Derdebin. He [Guy] immediately wrote back advising Giovanni

how to go about the migration process and offering to sponsor him. [19]

However, di Fabio failed to follow-up on the offer of

migration assistance from his wartime employer. Paul de Pierres' claim that

PW(I)s were “not much use for anything but basic labouring around the farm”

probably needs some explanation. As de Pierres points out, the three PW(I)s

employed at Derdebin were all of peasant farming background. What this meant,

amongst other things, was that they would have been quite unfamiliar with farm

machinery and WA's farming techniques and practices even though much of Italy

and WA's wheatbelt shared similar climatic conditions. And the PW(I)s had

little time to learn so as to become adept since they were only employed in

Wyalkatchem for slightly over one year, so less than just over one full

farming season.

One of the

often overlooked aspects of WA's wheat and sheep farming sectors' development

was the role of adolescents – farmers' children, most of whom could drive a

truck, a tractor and/or motorcycle by the time they were in their early teens,

knew how to handle large sheep flocks adeptly and undertook many other farm

chores, including being generally quite competent mechanically. Farming

childhood backgrounds meant having the opportunity to develop aptitudes that

were generally lacking in the case of the PW(I)s since these men had hailed

from vastly different agricultural backgrounds or perhaps even urban

environments. This meant wheatbelt farmers would have found such inexperienced

labourers, initially at least, not fully up to the tasks at hand. Moreover

such a lack of experience from their adolescent years may well explain, in

part at least, the fatal accident of 35-year-old Felice Marasco, a clerk in

civilian life, whose remains still lie at Wyalkatchem Cemetery. Marasco lacked

the years of practice that so many wheatbelt farmers had been able to gain

often since their childhood years.

Cappello's latter point, that the Italian PWs may well

have contributed to mellowing or modifying Australia's pre-war reluctance to

accept non-English speaking migrants is, however, most pertinent.

The more than dozen Eastern

European families who reached Wyalkatchem within five years of the Italian PWs

departure from Wyalkatchem District's many farms, to return to Italy, as

required under international law, were therefore not an entirely new factor in

the town's economic and social history. This point is made despite the fact

that the Italians were prisoners, even if they experienced a fair degree of

freedom, while the migrants were free people, just like all other Australians.

And this point is worth stressing because one of the major reasons most of the

East Europeans chose to emigrate to Australia was to ensure they did not live

in a Soviet or bolshevized society which required an inordinate degree of

social and economic regimentation, a political order than had been imposed

upon Poland after 1944 with its occupation by the Soviet Red Army. Another

reason the Italian PW experience is worth noting is that most of the migrants

reaching Wyalkatchem in 1950 or soon after had been farm labourers in the Reich so undertook work similar to that of these PWs.

Another possible reason for

growing post-war acceptance of non-English speaking migrants across WA was the

fact that most rural Australians had become increasingly aware that a huge

backlog of maintenance and repair work was required to publicly-owned

infrastructure. WA's quite extensive railway network was in disrepair, as were

its roads, and many other public assets. WA by 1950 was therefore in quite

desperate and urgent need of a boost to its skilled as well as unskilled

worforce. Not widely realized today is the fact that on many of the

wheatbelt's railway lines trains were often compelled to travel at extremely

slow speeds so as to ensure that the under-maintained and dilapidated tracks

did not give way beneath the loads. Sleepers below the tracks were prone to

sink into unhardened surfaces thereby leading to derailments.

Differences Between Italian Prisoners of-War

and Post-War Eastern European Migrants

As already stated, unlike their Italian predecessors the

Eastern Europeans were not prisoners. They were like the freemen and women who

migrated to the Swan River Colony, as the Perth area came to initially be

known, during and after 1829, so were not like Western Australia's convicts of

the 1860s to 1880s, who it is more accurate to compare to the PW(I)s when

working as farm labourers. It should be added, however, that the PW(I)s were

paid and after the war many indicated they wished to remain in WA rather than

be repatriated to Italy. In this latter respect they were like Western

Australia's 1860s to 1880s convicts. Permitting the PW(I)s to remain in the

state afters the war had ended was not an option for the Australian Government

since it was required under international law to return all such prisoners to

their homeland. Notwithstanding this some PW(I)s opted to simply escape and

hide rather than return to their post-Mussolini homeland. Others returned to

Australia soon after reaching Italy. In light of this one should therefore be

cautious about being too hard and fast when making the comparison with WA's

convict era. [20]

The Eastern Europeans and Dutch also came with spouses,

and in most cases at least one child, whereas the Italians were an all-male

contingent having been soldiers in North Africa who had been captured far away

from kith and kin. As will be seen below this meant that wives accompanied the

post-war intake and thus the town's workforce was further boosted since most

of these women quickly found employment either as private domestics on

outlying farms, or else at the Wyalkatchem Hotel, the hospital and/or the

drycleaners.

Because most of

those reaching Wyalkatchem in 1950 and shortly after also had children this

was to mean that the town's post-war baby boom of farmers' children as well as

those in the town began to mix and make friends with non-Australian children

from the outset of the 1950s. This new generation of Western Australians was

therefore the first to be exposed to non-Anglo-Celtic sensibilities and

cultures, a major difference between themselves and their parents' childhoods.

Furthermore, since most of the

migrants were Catholics the town's Catholic population was also markedly

boosted and this helped to act as a catalyst for the construction of the

Presentation Sisters' Convent in 1953. Of the 40 students attending in that

inaugural year at least 10 per cent were offspring of migrants from the

outset. But this number and proportion was to rise with the birth of a first

generation of Australian-born offspring of the migrants. [21]

Captured in Battle or in a Lapanka

Finally, it is necessary to highlight what may not be an

obvious similarity between Wyalkatchem's wartime PW(I)s, who worked in the

district during 1944 to 1945, and the town's post-war primarily Polish and

Ukrainian refugees who were residents between 1950 and about 1970. Both the

PW(I)s and the succeeding refugees reached the town or district because they

had been captured, one way or another. In the case of the former, the PW(I)s,

they were captured by British or Australian forces on one of the battlefields

of North Africa or in states of the Horn of Africa, such as Somalia or

Abyssinia (Ethiopia) by British colonial Indian troops. However, many of

Wyalkatchem's refugees, despite being civilians, had also been captured, or,

more accurately, kidnapped by members of one of the Reich's many policing

agencies. Or perhaps it is more accurate to say that they were press-ganged

into working in the Reich. In other words, they

were subjected to the same treatment experienced by so many 18th and early 19th

century Englishmen who had gone to sea forcibly with the Royal Navy by being

press-ganged, that is, caught on a street or in public house and taken to a

ship against their will. Several of Wyalkatchem's migrant menfolk, of course,

experienced military capture and thus internment, like Wyalkatchem's earlier

PW(I)s. What this meant was that virtually all those who reached the town in

1950 or soon after had begun their journey to this representative WA central

wheatbelt town a decade or so earlier, by being forcibly removed from their

home, and therefore Poland. In light of this it's little wonder that during

the war the Poles used a word to describe such kidnapping or press-ganging of

civilians, a permanent threat hanging over the entire population between 1940

and 1944. And that word was “lapanka” with the

first letter, “l”, pronounced like the English letter “w”, so it is

pronounced, WA-PUN-KAH. This word is related to the Polish verb, “zlapac”, meaning, “to catch”, and is related to

another Polish word, “lapa”, meaning, paw or claw,

in other words, the end portion of the limbs of an animal like that of a lion

or a tiger, which seems appropriate in light of the treatment that so many

civilians endured. The Kosciuszko Foundation Dictionary defines “lapanka” as a: “(police) round up (of civilians during

the German occupation, 1939-1945).” [22]

As the war continued and the

German or Reich economy required ever more workers

to replace the German and Volksdeutsche (ethnic

Germans living beyond the Reich's 1938 borders)

menfolk who were being conscripted into Germany's armed forces. This meant

there was to be an increasing reliance on forcibly recruited Polish,

Ukrainian, Yugoslav and other including even from Western Europe workers to

help maintain industrial and farming output to pursue Hitler's war aims, which

were primarily focused upon defeating and destroying the Red Army so that the

top secret Hitler/Himmler Generalplan Ost could be

implemented. This little known plan envisaged the steady expulsion of millions

of Slavs into Western Siberia and the settling of Germans from the Reich and other parts of Europe upon traditional

Slavic lands - Poland, Bohemia-Moravia (Czech Lands), Belarus, Ukraine,

Russia, and Slovakia. [23] But it is the demand for

wartime labour explains why so many of those who reached Wyalkatchem –

including women - after 1950 had been victims of a “lapanka”. Unless such people had been soldiers they

had invariably or generally been press-ganged into working in the Reich. As things transpired this was to be their first

step in coming to spend the remainder of their lives in Australia.

The Third Reich's Insatiable

Demand For Labour

Georgia Institute of Technology academic, assistant

Professor of modern German history and history of technology, Michael Thad

Allen, in his book, The Business of Genocide – The SS,

Slave Labor and the Concentration Camps, has focused on the role of

foreign workers in the Hitler war effort. [24] Although

the primary focus of Allen' study is the role and treatment of concentration

camp labour – like that endured by Helena Poprzeczna in and around

Auschwitz-Birkenau for nearly two years - the work undertaken outside such

camps by nearly all the Poles reaching Wyalkatchem was also crucially

important in the Reich's war efforts. Those

reaching Wyalkatchem, with the exception of Helena Poprzeczna, were generally

PWs or simply press-ganged labourers, who had endured a lapanka, and were then forcibly directed to farming

chores, like her husband Jozef who had been dispatched to Lorraine. One of

Allen's observations is worth quoting here since it helps put into context the

treatment most of Wyalkatchem post-war settlers underwent.

To German management fell the

daily task of configuring modern production around these [foreign] labourers

in a last-ditch effort to match the Allies tank for tank and plane for plane.

Foreign civilians made up the majority of this compulsory labour force.

Limited recruitment campaigns for foreign workers had started as early as

1940, but after March 1942 a special “General Plenipotentiary for the Labor

Action” began large round-ups of “Eastern Workers” to ship west to German

factories. Over 700,000 concentration camp prisoners laboured under the most

brutal conditions, and even if they formed only a small part of the overall

German war economy, by 1944 hardly a single locale with any factory of note

lacked a contingent of prisoners. [25]

It is worth seeing the fate of

those who reached Wyalkatchem in light of the decision to launch large

round-ups across Poland after March 1942. Although I have been unable to

establish the exact date that each of Wyalkatchem's “eastern workers” was

press-ganged into working in the Reich it is likely

that most, if not all, were caught after March 1942. I know that my father was

arrested in March 1942 for no cause while at Koluszki railway station waiting

for a train get to Piastow, which is to the west of Warsaw, because he was

placed on a Reich-bound train in Czestochowa, where

he was interned for a brief period, on the 17 March, his birthday. This

suggests he was press-ganged in the first wave of arrests.

The Ships

That Brought Them to Fremantle

TheE information about individual ships identified in this

section has been largely obtained from leading Australian maritime historian

Peter Plowman's classic, Emigrant Ships to Luxury

Liners: Passenger Ships to Australia and New Zealand, 1945-1990, which was published by the New South Wales

University Press in 1992. This book not only carries quite detailed historical

descriptions of each ship but also photographs of most of them so is worth

consulting, especially if one wishes to be reminded what the ship one arrived

in Australia looked like. If not all, then most of these ships have now been

broken up for scrap so can never be seen.

Anna Salen [26]

The Anna Salen was built in 1939 and initially known as the

Mormacland. Her builders were Sun Shipbuilding & Dry-dock Co., Chester,

and the contract was for Moore-McCormack Lines. This 11,672 gross tonne vessel

was 494 feet by 69.2 feet, with a single screw and had a service speed of 17

knots. In 1940 she was acquired by the US Navy and refitted to become an

auxiliary aircraft carrier. However, in 1941 the Royal Navy commissioned her,

HMS Archer, and she served as a convoy protector.

These were the days of American Lend-Lease with US President Franklin D.

Roosevelt's moving to save Churchill's Fortress Britain in the face of

domestic isolationism in the immediate post-Dunkirk era. As HMS Archer she collided with, and sank, the American SS

Brazos on 13 January 1942. Because she was so badly damaged HMS Archer had to be towed stern first to Charleston,

South Carolina, for extensive repairs. In 1945 the US Ministry of War

Transport took her over and renamed her simply Archer and had her refitted as

a cargo ship. She was managed by the Blue Funnel Line and subsequently renamed

the Empire Lagan. In 1946 she was returned to the

US Maritime Commission.

Her

next owners were Sven Salen of Stockholm with her registration under the

ownership of Rederi A/S Pulp. Now rebuilt as a passenger ship, with

accommodation for 600 single class passengers, Anna

Salen was set to become an emigrant ship for destinations as far away as

Australia.

In December 1949,

Anna Salen broke down off Aden and her passengers

were transferred to another legendary migrant ship, the Skaugum, which at the time was making its way back to

Europe from Australia. This mishap was to be the only such incident in the

transfer of well over 10,000 migrants to Australia over the late 1940s and

early 1950s, the years of Australia's peak migrant intake. Anna Salen next docked in Fremantle on 31 December

1950, even though this trip was destined for Melbourne, and a result, WA's

population was unexpectedly boosted by 1500 people with Victoria missing out

on that number. After mid-1953 she was used for round voyages between Bremen

and Quebec.

In 1955 Anna Salen was sold to Cia Nav.Tasmania, Piraeus in

1955, renamed Tasmania and put on the Piraeus-Melbourne service for the

Hellenic Mediterranean Line. Three years later she was rebuilt to be a 7638

gross tonner and in 1961 was sold to China Union Lines of Taipei and renamed

Union Reliance. In November that year she collided with the Norwegian tanker

Beran in the Houston Ship Channel, Texas, and was beached on fire, after which

she was towed to Galveston and sold two months later to be scrapped at New

Orleans. The Piekarczyk family were to reach Fremantle aboard the Anna Salen.

Castelbianco

Plowman points out that what

came to be known as the Castelbianco was one of the

so-called “Victory” ships built in the United

States as part of its wartime armament program. Ships in this class were

mass-produced like the far better known “Liberty” ships of that global

conflict. The Sitmar Line acquired the Vassar Victory from the US Maritime

Commission and renamed her Castelbianco, which was

refitted in late 1947 so as to be capable of carrying some 900 passengers in

segregated quarters. Furthermore a single deck of superstructure was also

added. [27]

Vassar Victory had been built

in 1945 by Bethlehem Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. She had a gross tonnage

of 7604 tonnes and was capable of a service speed of 15 knots. Propulsion was

by geared turbines with a single screw. Her dimensions were 455 feet long and

62 feet wide (138.7 x 18.9m). In July 1947 mass resettlement of refugees in

the former Reich commenced with the signing of a

contract with IRO for a number of ships that would be used to transport these

people to countries beyond Europe that either had already or would be

accepting them. Castelbianco was among the first

group of ships earmarked for this task. The first voyage to Australia by one

of these ships was that of Castelbianco, which

arrived in Sydney on 23 April 1948 from Europe via Madras. She was to make a

further trip later that year leaving from Genoa and several more over 1950 and

1952. In 1952 she was reconstructed and had her tonnage increased to 10,139

tonnes and was re-named Castel Bianco. From 1953

she began operating between Genoa to Australia, with this later being changed

to Bremerhaven. Sitmar sold her in 1957 to the Cia. Transatlantica Espanola,

known also as the Spanish Line. Castel Bianco was

again renamed, this time to Begona.

Dundalk Bay

The

7105 tonne Dundalk Bay

was built in 1936 by Bremer Vulkan, Vegesack, for the North German Lloyd. It

was named Nürnberg and was to be one of five

sisters which carried the name of a significant German city. The others were:

Dresden, Leipzig, München and Osnabrück. These general cargo ships plied between

Bremen and the west coast of the United States, via the Caribbean, and could

each carry up to a dozen passengers. Nürnberg

turned around in San Francisco and was used to carry tropical fruit such

as bananas from islands like Jamaica during these years. With the outbreak of

war in September 1939 Nürnberg was put into service

as a mine layer in the North Sea and later became a German military

accommodation and storage vessel in the Danish port of Copenhagen for

occupation forces where it was taken as war booty by the British in the spring

of 1945.

Two years later the

Nürnberg was sent to Britain and used for a short

time as a depot ship then sold to H.P. Leneghan & Sons Ltd, of Belfast,

who operated the Irish Bay Line. As the Dundalk Bay

– so named after a bay south of Belfast - was used as a refugee transport

vessel. Plowman said of her:

Very austere quarters for 1025 persons were

installed in the former cargo spaces, but the superstructure was only

slightly enlarged. [28] The Dundalk Bay made her first trip to Australia, out of

Trieste, on 15 March 1949, bringing some 1000 passengers. She made two more

trips to Australia and New Zealand the same year. In early 1950 she was based

in Naples and it was from here that she made two sailings, the first in

January, to Melbourne, and the second in March to Fremantle. It was on the Dundalk Bay's second or March trip in 1950 that the

Bajkowskis, Baluchs, Marcinowiczes, Olejaszes, Poprzecznys, Przybywoliczes and

Zuglians came to WA. [29]

Goya

The Goya commenced its life as a fast cargo ship under the

name Kamerun. She was built by Bremer Vulkan, Vegesack, for the Woermann Line

and was launched in May 1938. Kamerun and her sister ship, Togo, were employed

on the Hamburg-West Africa run. With the outbreak of war she was requisitioned

by the German Navy for use as a repair ship and carried out these duties

throughout the entire war. In May 1945, the month Hitler's Reich unconditionally surrendered, the Kamerun was

handed over to the Norwegians as war reparations. Two years later she was

renamed Goya and acquired by the Norwegian line, L.

Mowinckels Rederi, for use as a cargo ship. The Goya was a 6789-tonne vessel, and was 438 feet by 58

feet (133.8 x 18m). She was diesel powered with a single screw and could

travel at a service speed of 15 knots. Two years later, in 1949, Mowinckels

Rederi gained a contract from the IRO to transport refugees so Goya was converted to a passenger carrier. The

refitting and refurbishing meant that the Goya was

capable of carrying 900 passengers.

Goya made four migrant carrying

trips to Australia. The first was in March 1949 from Genoa and it was on this

voyage that Janis and Helena Saveljevs were passengers. Plowman writes:

During September and October 1947,

authorities from the Australian Government visited camps in Germany housing

displaced Balts, people from Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, whose homelands

were now under communist control. A total of 842 were selected to be taken

to Australia as migrants, and this group was taken to Bremerhaven . . . [30]

Goya's three remaining Australian trips were all from

Bremerhaven, Germany, and were made during 1950. In 1951 Goya made three trips to New Zealand also carrying

migrants. Plowman says that this marked the end of her career as a migrant

ship. In 1953 the Goya was to be again as a cargo

ship.

The Mowinckels Rederi's

Goya should not be confused with a passenger/cargo

ship of 5230 tonnes of the same name that had been built in Norway for the

Hamburg-America Line. This other Goya was acquired

by the German Navy to help in the mass evacuations from the Hela Peninsula in

the Bay of Gdansk (Danzig) of some two million people and nearly

three-quarters of a million soldiers during 1945. This operation, sometimes

referred to as Germany's "Dunkirk" was undertaken to move Germans from

present-day northern Poland who were fleeing the Red Army which was advancing

upon Berlin.

When the Norwegian-built Goya

was nearly 100-kilometres off the Baltic port of Stolpe, and carrying members

of the 35th Tank Regiment plus several thousand

refugees, she was attacked by the Soviet submarine L-3. Two torpedoes struck

her amidships after which she broke in half and sank in less than five

minutes. Of Goya's nearly 6400 passengers fewer

than 200 survived, meaning this 16 April 1945 disaster witnessed many more

deaths than the sinking of the Titanic. [31] Of the estimated 7000 aboard Goya only 183 were rescued

General W.

C. Langfitt

The General W.C. Langfitt was one of 10 American World War

II fast troop carriers that were to be used on the IRO's program of relocation

of refugees from post-war Europe to the New World, including Australia. Most

of these people were, at the time, housed in camps in Germany and Austria, so

the former Reich. These ships were collectively

referred to as the “Generals” since they had all

been named after an America general. [32] According to Plowman the

General W.C. Langfitt made her first refugee or

migrant trip to Australia in June 1949. Its second was in September the same

year and the third in February 1950. This last trip was from Mombasa, Kenya,

to Fremantle and was the one that the three members of the Kozlowski family

was relocated to WA on after they had spent the second half of the war and the

remainder of the 1940s in East Africa having reached there via Iran out of

either Kazakhstan or Siberia where hundreds of thousands of eastern Poles had

been deported in 1940 and 1941 by Stalinist ethnic cleansing agencies.

Skaugum

The Skaugum was German-built

and was to be rebuilt in 1949 by Germaniawerft, Kiel and Howaldswerke, Kiel.

Skaugum had a tonnage of 11,620 tonnes and her

dimensions were 552 feet in length and 66 feet wide. She was powered by a

diesel electric engine with twin screws and had a service speed of 15 knots.

When launched Skaugum was known as the Ostmark, and was sister ship to the Steiermark, a ship that has considerable and tragic

relevance in the history of the Royal Australian Navy.

With the outbreak of war Steiermark was renamed Kormoran and was converted into a raider. And it was

this ship that sank the HMAS Sydney off Carnarvon, WA, resulting in the loss

of 648 Australian seamen; so all hands. [33] Ostmark, or the future Skaugum, was launched in January 1940, so four months

after the outbreak of the war. The fact that the building of the Ostmark was completed after the outbreak of war meant

that it was “towed to a quiet backwater and laid up in this incomplete state

for the duration of the war.” [34]

When the Allies entered Kiel in

May 1945, the British claimed Ostmark as a prize of

war, and she was placed under the control of the Ministry of Transport. In

1948, the Minister of Transport sold Ostmark to the

Norwegian shipowner, Isak M. Skaugen, who owned a number of freighters and

tankers. [35]

A year later, after Isak M. Skaugen gained a contract to

transport Displaced Person for resettlement beyond war-devastated Europe, she

was re-built for this purpose and made her maiden voyage nine years after

being launched. She made trips to Melbourne in May and July 1949. During

November the same year she left Naples for Newcastle with 1700 passengers.

Plowman provides an account of an incident that many migrants, even those who

were still minors during the 1950s in Wyalkatchem, are likely to recall having

been occasionally discussed by adults.

In December 1949, Skaugum was

crossing the Indian Ocean returning to Europe empty, when another IRO ship, Anna Salen, developed engine trouble while outward

bound with 1600 persons on board. Anna Salen had to

return to Aden, and Skaugum was also directed

there, to take on board the displaced persons from Anna

Salen and carry them to their destination in Australia. [36]

Skaugum made four further trips

to Australia during 1950; in March from Naples to Melbourne; from Bremerhaven

to Fremantle in June; in August also from Bremerhaven to Fremantle; and her

last such trip in November from Naples to Melbourne. In 1964 she was sold to

Ocean Shipping & Enterprises and renamed Ocean Builder and sailed under

the Liberian flag. The Roszak family reached Fremantle aboard the Skaugum in July 1950, along with the Chorza-Purkhardt

and Szczesny families.

|

Ship[37] |

Arrival Date |

Total Landed |

|

General Stuart

Heintzelmann |

1948-February 13 |

125 |

|

Kanimbla |

1948-October12 |

429 |

|

Amapoora |

1949-April 19 |

617 |

|

Mozaffari |

1949--May 21 |

902 |

|

Goya |

1949-June 22 |

899 |

|

Amapoora |

1949-July 22 |

612 |

|

Anna

Salen |

1949-August 24 |

1566 |

|

Oxfordshire |

1949-September 9 |

675 |

|

Anna

Salen |

1949-October 10 |

256 |

|

Skaugum |

1950-January 6 |

1543 |

|

General

Langfitt |

1950-February 15 |

1164 |

|

Fairsea |

1950-March 2 |

1898 |

|

Dundalk

Bay |

1950-March 29/ |

1019 |

|

Oxfordshire |

1950-June 11 |

671 |

|

Skaugum |

1950-July 12 |

1823 |

|

Skaugum |

1950-September 24 |

1854 |

|

General

Hersey |

1950-November 3 |

1370 |

|

Anna

Salen |

1950-December 31 |

1522 |

|

TOTAL |

|

18945 |

Of the

19,000-odd Displaced Persons reaching WA over the three years 1948-50, 8236

were from Poland. Those categorized as hailing from Yugoslavia numbered 2892,

with nearly 2000 from Latvia. Those from Ukraine, or more correctly, the

Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine, numbered 1254, which was just below the

Hungarian component of 1320. The other large group was from Lithuania,

numbering 1051. Other countries represented were: Estonia (524); Romania

(174); Czechoslovakia (842); Russia (318); Germany (152); Bulgaria (91);

Albania (25); France (7); Belarus (5); and one each from Belgium, Luxemburg,

Spain and Switzerland.

These

figures should not be seen as reflecting exactly the ethnic break-up of these

newcomers since some may well have been Jews, while others who hailed from

pre-war Poland were Ukrainians. It is also possible that some of those giving

Czechoslovakia as their country of origin may have been Sudeten Germans. The

same may also apply to some giving Hungary as their nation of origin since

that country had a sizeable German minority, some of whom had adopted

Hungarian names under Budapest's pre-war Magyarization program. [38]

Finally, of the 19,000-odd Displaced Persons reaching WA

during 1948-50 about 14,200 were adults with children making up nearly 5000,

so roughly a three-quarter to one-quarter breakdown.

Although a precise average age

cannot be given a scan of the Dundalk Bay's passenger roll shows that most

males were in the 25-35 age group while females were markedly younger,

probably averaging around 25, certainly below 30. What this meant was that

Australian migration officials were selecting on the basis of age and that

those who arrived did not retire from the workforce until about 35 to 40-years

later, so in the late 1980s or the early 1990s. With migrant women generally

entering the workforce most of the 14,200 adults were therefore additions to

WA's workforce, meaning the program succeeded in the sense that it gained a

sizeable number of workers. Offspring of these migrants entered the workforce

alongside Western Australians who were in the so-called post-war baby boom

cohort, therefore adding signficantly to the state's need for workers when it

witnessed a marked boost in economic development and growth following the

emergence of the Pilbara as a major international mining region after 1964. In

this regard, therefore, this WA migration chapter must be judged as having

been successful.

Western Australian Immigration Centres

Between 1947 and 1954, the years

which well and truly cover the post-war refugee or Displaced Persons intake

that's pertinent to Wyalkatchem, the Commonwealth Department of Immigration

had no fewer than 11 immigration centres in WA that were transit residential

establishments. The one most of Wyalkatchem's migrant settlers lived in was

the Holden Immigration Accommodation Centre in Northam, which opened in 1949

and remained operational until 1957, and again during 1962-63. During 1949-51

there was also what was generally referred to as the Northam Army Camp

(Northam Reception and Training Centre). The Holden Centre had a capacity of

some 850 persons, while the Army Camp could hold up to 4500.

Cunderdin was also briefly a venue

for a transit camp, the Cunderdin Migrant Centre, which had a capacity of

between 700 and 750 persons. It was operational between 1949 and 1952. During

the war years it had been the RAAF base where air crew were trained under the

Empire Air Training Scheme that saw several thousand airmen trained across the

British Empire, especially for Bomber Command that operated out of England

against Reich cities and industrial targets. In

addition to Cunderdin, Albany and Collie had migrant hostels that could each

accommodate about 200 persons. Both these were operational during 1951 and

fell under the control of Commonwealth Hostels Pty Ltd.

In metropolitan Perth, Graylands

was the venue for the Immigration Centre (1947-54). Graylands and Dunreath

Hostel in Belmont were also Commonwealth Hostels Pty Ltd venue. Swanbourne

Migrant Centre, with a capacity of 500 persons, was operational between 1947

and 1949. This, however, was a refurbished military camp and had been loaned

by the Army to accommodate migrants. Nearby Karrakatta's Army Camp was briefly

used during 1947 to accommodate Polish servicemen from Britain who were en route to work on the Tasmanian Hydro-Electric

Scheme. And after 1947 the Point Walter Migrant Hostel, with a capacity of

about 500, was also utilized.[39]

[1] Perhaps the most comprehensive English

language account of the movement of some 120,000 Poles out of Soviet Siberia

and Soviet Central Asia, primarily Kazakhstan, in 1942-43 to East Africa and

Rhodesia, via Iran, Iraq and British India, and later on to Australia, Canada,

the United States and England, is carried in: Krolikowski, Lucjan, OFM. Conv.

Stolen Children: A Saga of Polish War Children. (Buffalo, New York). 1983. The

author is grateful to Elizabeth Patro of Dianella for information about the

Kozlowski family. Mrs Patro attended the same school as Rozalia's in Koja

Camp, Uganda, throughout most of the 1940s. She also intermittently met

Rozalia after both had reached Fremantle in February 1950, the last time being

in 1954 or 1955 in Perth. None of the Poles who knew the Kozlowskis, either in

Uganda or WA, were able to advise the author of their whereabouts after the

mid-1950s.

[2] For a detailed but concise study and

analysis of Auschwitz-Brikenau see: Sybille Steinbacher's: Auschwitz – A

History. (Penguin Books), 2004.

[3] The Poprzeczny family lived briefly in a

transit camp at Dietz, on the eastern side of the Rhine and to the north of

Frankfurt-on-Main.

[4] The single most

important contributions to Labor's socialisation and centralization (abolition

of the states) planks was Melbourne lawyer, Maurice Blackburn. Labor's

thinking since the days of Blackburn and the late 1940s, indeed, right into

the early 1980s, was essentially unchanged. Since then, however,

Liberal-National Party Government, especially the one led by John Howard, have

moved for ever greater centralization by Canberra's bureaucracies. [5] Reginald Appleyard;

"Displaced Persons in Western Australia. Their industrial location and

geographical distribution: 1948 to 1954", University

Studies in History and Economics, Vol. II, No. 3, 1955, pp. 63-64. [6] Peter Plowman; Emigrant Ships to Luxury Liners:

Passenger Ships to Australia and New Zealand, 1945-1990. (University of New

South Wales Press), Kensington. NSW. 1992. p. 7.

[7] Joseph Poprzeczny; Hitler's Man in the East:

Odilo Globocnik. (McFarland & Co. Inc. Publishers). Jefferson, North

Carolina. 2004. p. 64.

[8] Peter Plowman; Op. Cit. p. 7.

[10] Information Sheet. The Army Museum of

Western Australia, Artillery Barracks, Burt Street. Fremantle. WA. 16 August

1995.

[11] The author cannot provide the source but

vividly recalls reading an article either about or by the well-known former

electronics retailer, Dick Smith, who specialised in travelling long distances

by helicopter. At one stage Smith undertook a helicopter flight along the

Trans-Australian Railway Line either from Kalgoorlie to Port Pirie or

vice-versa. To his amazement Smith noticed a symmetrical or orderly

arrangement of several hundred white stones near the line in the middle of the

Nullarbor and for some time wondered what this was and who had set them out in

such an orderly manner. It was later determined that the stones had been laid

out in a pattern as part of demarcations between tents of and pathways of a

work camp that had been used by PW(I)s employed on this railway line.

[12] Army Museum Information Sheet.

[13] Ibid. (The Army Information Sheet says

that by December 1946, 32 POW escapees were still at large in WA. Of these one

was never recaptured while the last was captured in 1951 and returned to

Italy. Four Italian and 13 German POWs were permitted to remain in Australia.

The author met and interviewed one of these Germans, Gunther Kuhlman, in the

1990s. He had been a civilian cook aboard a German merchant marine vessel that

was blockaded at the western end of the Persian Gulf by the outbreak of World

War II. Kuhlman was captured in 1942 in the port of Basra, Iraq, following an

Allied action against Kuhlman's ship and several other Axis vessels that had

by then been blockaded for nearly three years. Kuhlman was brought to Western

Australia and was detained at Marrinup POW Camp. After the war Kuhlman

requested that he be allowed to remain in Australia and was permitted to do so

since he had never been a member of the German Navy or any other Axis fighting

arm He was a merchant marine man. After his release he developed a successful

bakery and pastry business in the Fremantle-Mosman Park area. Consequently,

Kuhlman and the other dozen Germans were technically the first post-war German

migrants to Western Australia, even though they had reached Australia's shores

ahead of Wyalkatchem's Polish and other East Europeans.)

[14] John C. Rice:

Wyalkatchem – A History of the District. (Wyalkatchem Shire), 1993. p. 314.

[15] The author is

grateful to Ballajurra historical researcher, Ernest Polis, for the details on

Italian prisoners-of-war detained in WA and disbursed across the state's

wheatbelt region, most especially the information about Wyalkatchem's

Prisoner-of-war Control Centre. For further information see Polis's:

“Marrinup: A Cage in the Bush. (2005).” Additional information on this aspect

of WA's wartime economy can be found in Rosemary Johnston: Marrinup

Prisoner of War Camp - A History. (1986) and a broader general survey of