|

Introduction

Preface to the 2005 Edition || 1: MAYPORT

by

Donald J. Mabry

@ 2005 Donald J. Mabry

Ed Smith wrote for family and friends when he penned

nostalgic essays about life on "Mayport and the Beaches," communities

on the northern end of a

narrow barrier island off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida. Although the

essays are pleasant reads for those who know the area and even more so for those

who knew the people, providing background on the places and people makes his

book more valuable as a glimpse into life in what was a backwater in the first

half of the twentieth century. Few today would recognize the area about

which Ed Smith wrote. Higher incomes, cheap air conditioning, better and more

divided highways, the dramatic expansion of the Mayport

Naval Station into the second largest naval installation on the U.S.

Atlantic coast, and the growth on Jacksonville into a megalopolis of more than

one million people, the sprawl of housing developments, and the destruction of

historic housing for the benefit of condominiums in the thirty-two years since

he wrote his book in 1973 make Mayport and the beaches almost unrecognizable.

Only the Atlantic Ocean, Pablo Creek/San Pablo River1,

and the St. Johns River seem constant. This outline map of Duval County, Florida shows the

geographical relationship of these communities. Ponte Vedra Beach and Palm

Valley are in neighboring St. Johns County.

In the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, the

island was relatively isolated and very sparsely populated. The northern

boundary is

the St. Johns River. To the east is the Atlantic Ocean. To the west, are rivers

such as Pablo Creek/River and the Tolomato River plus a canal through the Diego

Plains connecting the two. On the south, near Vilano Beach, the Tolomato River

enters the Atlantic. The island is now tied to the mainland by a number of

bridges and one can easily forget that one is going onto an island for the width of

the waterways is not that great. The communities on the northern

end of the island, the subject of the book, are Mayport, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, and Jacksonville

Beach in Duval County and Palm Valley and Ponte Vedra Beach2 in

adjacent St. Johns County. Mayport, the oldest settlement, was considered as a

separate community until Jacksonville became synonymous with Duval County.3

Both Ponte Vedra Beach and Palm Valley are unincorporated

communities in St. Johns County.

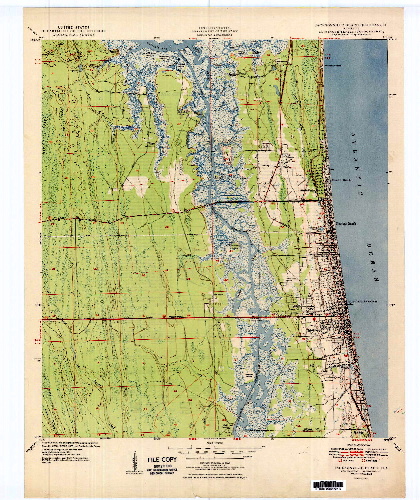

This topographical map of the Beaches area shows

that the area was largely sand dunes, swamps, marshlands, and creeks with only a

narrow band of development as late as 1949. The village of Mayport and the Naval

station are not shown on this map. They are located north of the area shown.

Similarly, only the northern tip of the Ponte Vedra Beach-Palm Valley area are

shown in the lower right hand side.

Click on the map to enlarge it

Living on a remote barrier island off the coast of

Jacksonville in North Florida in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had to

be tough, even for people accustomed to hardship. The best route to

Jacksonville was traveling on the hard-packed beach at low tide to Mayport and

hen by boat or ship up the St Johns River. Getting to

Mayport was a two hour trip on the and then getting to

Jacksonville was a three-hour trip upriver. Still, it was easier than

going due west for 15 or miles at least the river provided smooth

passage.

Settlement clustered in the fishing village of Mayport, originally

founded by

French Huguenots in the 16th century. In addition to fishing and a little

farming, people and

goods coming or going to Jacksonville or could be offloaded there. The village

contained about 600 people in 1864. Entrepreneurs

tried to develop a tourist trade by building a few hotels on Burnside Beach on

the coast but fire destroyed their dreams so the area remained small. Not

until the U.S. Navy decided to build a naval base on Ribault Bay did Mayport

change.

Jacksonville Beach had better luck because a narrow gauge railroad

ran from

south Jacksonville to Pablo in 1886. Eventually two railroads ran

east from Jacksonville—one to Mayport, the other to Jacksonville Beach. That drew

a few people, many of whom lived in tents. That was the situation of William E.

and Eleanor Scull in 1884. She was the postmistress of the Ruby Beach Post

Office named after their daughter. They lived in one tent and ran a store

and post office from the other tent. A resort hotel, the Murray

Hall, was built in 1886 but it lost money and was destroyed by fire in 1890. Then, in 1900, Henry Flagler,

Standard Oil magnate and railroad builder, acquired the Jacksonville Beach

route, eventually extending it to Mayport. He Flagler built the luxurious Continental

Hotel in Atlantic Beach in an effort to build tourism. Like other hotels at the beaches,

it was destroyed by fire. The railroad was removed in 1932 because automobiles

and trucks made it redundant. Although the opening of Atlantic Beach Boulevard, paved with

shells, in 1910 from

south Jacksonville made access to the island easier, few people owned cars. The automobile age

which began in the 1920s would kill the railroad. As George Simons notes, 116,000 cars

were registered in Florida in 1922, 286,000 in 1925, and 460,900 by 1942. The St

Johns River was spanned in 1921 and Atlantic Boulevard was modernized as a

paved road in 1925.4

Still, few people moved to the island until the 1930s and

1940s. Pablo Beach had only

249 inhabitants in 1910, 357 in 1920, and 409 in 1930.5 In spite of

the Great Depression and the loss of Neptune Beach in 1931, Jacksonville Beach

grew to 1049 in 1935 and 3566 in 1940. Neptune Beach grew from 350 in 1935 to

1363 in 1940. Atlantic Beach contained only 164 people in 1930 and 468 in 1940. Palm Valley had only a few hearty pioneers.6

Mineral City was renamed Ponte Vedra Beach in 1928 but its

conversion to a luxury resort and residential area was slow.

The beaches did develop as a resort. Winter tourists went

further south but summer tourists from north Florida and south Georgia

flocked to the amusements along the

boardwalk in Jacksonville Beach and the sand throughout the beaches. Bath

houses, rooming houses, hotels, and, eventually, motels provided places to stay

for tourists and employment for the locals. A roller coaster, merry-go-rounds,

bumper cars, and other rides thrilled kids and adults. Restaurants and bars

satisfied basic needs. Although the main season lasted but five months, it

provided a living for those who didn't survive by commuting to Jacksonville or

fishing. The beaches were a satellite of Jacksonville and their fortunes were determined by it.

World War II changed the area. The riverport became a seaport.7 The U.S. Navy expanded and

built new bases. Navy personnel from Jacksonville came to the beaches for

recreation and some stayed but it was the Mayport Naval Base that made the

beaches area grow quickly in the 1940s and the 1950s as Mayport Naval Station

became an important aircraft carrier base. Government money flowed into all

manner of enterprises. Jacksonville Beach grew from 3,566 people in 1940 to

5,943 in 1945 to 6,430 in 1950 and 12,053 in 1960. By 1945, Atlantic Beach had

956 people and Neptune Beach had 1,298. Even so, the beaches area was a small

town in 1960 quite a distance from Jacksonville. Although there were two very

good highways and regular city bus service connecting the beaches and

Jacksonville, it was still insular. Even the many who commuted the 15-16 miles

into Jacksonville to work saw themselves as being different.

Jacksonville moved the town limits to the town limits of the beaches in 1968

as it and Duval County (save Atlantic, Neptune, and Jacksonville Beaches and the

west Duval town of Baldwin) became one. Now the San Pablo River became the

dividing line. As the national economy boomed in the 1960s, so, too, did that of

the Jacksonville area. Improvements in its shipping capabilities through

dredging of the St. Johns River and improvements in it port facilities had

dramatically increased its importance as a trade center. Prudential had

established its south central office there in the early 1950s, paving the way

for other financial institutions. People migrated to Florida, including

Jacksonville. The Vietnam War meant billions of dollars spent not only on

payrolls and improvements at Mayport, Jacksonville Naval Air Station, and Cecil

Field but also on civilian activities. By 1970, Jacksonville had

grown to 528,865 persons; Jacksonville Beach to

19,000; Atlantic Beach to 6,132; and Neptune Beach to 4,281. Ponte Vedra Beach

had expanded commensurately. Palm Valley, that swampy area on the Intracoastal

Canal, also grew. The area was bustling. The vacant land close to the water was

virtually gone.

No wonder, Smith, who had come to the beaches in 1936 when it

was possible to know almost everyone, at least by sight, wrote of the good old

days. He could just as easily of termed that period "the world we have

lost." Surprisingly, he was not bitter. Instead, he looked to the future

with promise.

1. The name of this body of water varies.

Pablo Creek, Pablo River, and the San Pablo River are the same. Since it forms

an important part of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway, residents have often

referred to it as the Intracoastal. In recent decades, residents sometimes refer

to it as "the ditch," as in, "they live on the other side of the

ditch."

2. Mineral City was

renamed Ponte Vedra Beach in 1928.

3.. Baldwin west of Jacksonville and Atlantic, Neptune, and Jacksonville Beaches have their own city governments and, thus, retain most of their autonomy but the City of

Jacksonville performs many governmental functions for them.

4. George W. Simons, Jr., Report for the

Jacksonville Beaches Chamber of Commerce, 1944.

5. Simons, p. 7; Beaches Area Historical Society, October 19, 2005

via e-mail; Sidney P. Johnston, The Historic Architectural Resources of the

Beaches Area: A Study of Atlantic Beach, Jacksonville Beach, and Neptune Beach.

ESI Report of Investigations No. 382, July, 2003, pp. 8, 45, 52, 58, 66, 70, and

73.

6. Michel Oesterreicher, Pioneer Family: Life on Florida's

20th-Century Frontier. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1996 details

)how her parents settled in Palm Valley.

7. George E. Buker, Jacksonville: Riverport-Seaport. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1992.

|