© 2008 Donald J. Mabry

“Play Ball !!” the umpire shouts and America’s beloved game

begins. Permeating the air are the smells of grass, hot dogs, peanuts, popcorn,

Cokes, and, often, beer. Excited fans love the intricacies of the game, the theater on the diamond

as it were, as players and coaches duel. They cheer and boo. Few things define

America so much as baseball. In the 1950s, baseball was still the

great American past-time. Boys played on sand lots, in Little League and

similar organizations, high school, college, and, if skilled and lucky enough,

professional baseball. Girls and women played, too, but not so many. Both sexes

formed the large crowds which paid to watch a game. Sports pages of newspapers

devoted many column inches to the sport and specialized magazines promoted it. People

talked and argued about the fortunes and misfortunes of their favorite

teams—professional, college, high school. Some bet on the outcome of matches.

Major league players were heroes. Baseball movies drew crowds. Minor league

teams—divided in to Class AAA, AA, A, B, C, and D leagues with D being the

lowest—were ubiquitous. In 1950, there were 430 minor league teams in 57

leagues.[1]

Even small towns could host a low-level professional team. One such

"town" was on the northeast

Florida coast, eighteen miles east of Jacksonville, where the smell of the ocean

added to the allure of games.

The Jacksonville Beach Sea Birds offer a case study of the rise and fall of a minor league team. The Sea Birds played in 1952, 1953, and 1954 in the venerable Florida State League. The Sea Birds won more than they lost in the three years, coming in second in 1952; thus, they were better than the average minor leagues team and the team also produced some excellent minor leagues players as well as one major league player and manager. Yet, the team disappeared.

Source:

BAHS

Source:

BAHS

Jacksonville

Beach Baseball Stadium 1950 & the Atlantic Ocean

The locale is important to the story. Although the team was

named for one city, the home town audience was larger. Hugging the coast, the

Beaches[2]

consisted of the village of Mayport and the adjacent U.S. Navy base on the

south bank of the St. Johns River, the small cities of Atlantic, Neptune, Jacksonville

Beaches, the unincorporated settlements of Ponte Vedra Beach and Palm Valley in

neighboring St. Johns County, and the San Pablo Road area just west of the

Intracoastal Waterway. All except the last were on a lightly-populated barrier

island which stretched almost to St. Augustine. Most the land on the east

side of the Waterway was vacant; In 1950, about 12,000 or fewer people lived

there. Eighteen miles west of the Beaches was Jacksonville, the

county seat of Duval County, with 204,275 people. By 1950, there were two

highways to the Beaches: Atlantic Boulevard which separated Atlantic and

Neptune Beach and Beach Boulevard which used a former railroad right of way to

traverse from south Jacksonville to the ocean in mid-Jacksonville Beach. It

opened in late 1949 as a modern four-lane highway and refocused traffic to

Jacksonville Beach and its amusements. The building of a baseball park near

Beach Boulevard in 1950 enhanced the highway, which became U. S. 90.

Source:

Deane’s Studio

Source:

Deane’s Studio

Downtown Jacksonville Beach in the early 1950s

Jacksonville Beach was the business hub of the Beaches.

Atlantic, Neptune, and Ponte Vedra Beaches and Palm Valley were residential

except for a few businesses on the eastern end of Atlantic Boulevard. Mayport

was a fishing village. The Navy operated its own businesses and sailors also

shopped along the road leading to the beach and in Jacksonville Beach. The

Boardwalk stretched several blocks north from the Red Cross Volunteer Lifeguard

Station to the Sandpiper Hotel at N. 5th Avenue and the ocean. It

was an amusement park with games, food stands, carousels, Ferris wheels, bumper

cars, other rides, bars, bath houses, motels, and mercantile outlets. Close to the

oceanfront Boardwalk, there were restaurants, bars, liquor stores, motels,

hotels, rooming houses, bath houses, souvenir shops, and the other kinds of

commerce common to small towns.

The Boardwalk was the heart and soul of the summer tourist

season at Jacksonville Beach and its neighbors. Thousands descended during the

summer weekdays and tens of thousands during weekends. The key to the economic

prosperity was the attraction of more and more visitors to Jacksonville Beach.

The opening of Beach Boulevard meant many more day trippers from Jacksonville

because the highway was fast and direct and connected to the other major

highways passing through Jacksonville. Local businessmen, through the Chamber

of Commerce adopted a plan they hoped would maximize tourist traffic to the

Beaches via Beach Boulevard. They sought to bring minor league baseball to the

Beaches.

Jacksonville's baseball tradition extended back into the 19th century. The Jays played in the Class C South Atlantic League from 1904-10; was renamed the Tarpons for 1911-16; and then the Roses for 1917. World War I interrupted play. In 1921, a new team, the Scouts, played in the Class C Florida State League. They became the Indians in 1922. The Tars played in the Class B Southeastern League in 1926-30 moving to the Class B South Atlantic League from 1938-42 and the Class A South Atlantic League from 1946-1952. In 1953, the team became the Braves and stayed with that affiliation through 1960. Then the team changed names and affiliations again. The Jacksonville Red Caps played in the Negro American League in 1938 and 1941-1942; the city had a very large African-American population.

Spring training for Major League Baseball began in Jacksonville in 1888. The Washington Statesmen hosted the Philadelphia Athletics, Brooklyn Dodgers, Cincinnati Reds and Boston Nationals.[3] The Boston Braves (then called the Beaneaters) trained in 1906. The Philadelphia Athletics trained there in 1903, 1914-18; the New York Yankees in 1919-20; the Cincinnati Reds in 1905. The Brooklyn Superbas (Dodgers) trained in 1907-09, the Brooklyn Robins (Dodgers) in 1919-20, 1922; and the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1918.[4] After all, those were the days before Henry Flagler and Henry Plant had opened up Florida south of Jacksonville with railroads. Ironically, Beach Boulevard was built on the right of way of Flagler’s defunct spur line from south Jacksonville to the beach.

Jacksonville Beach businessmen cashed in on the area's historic affinity for professional baseball by daring to a ballpark a few blocks south of the Beach Boulevard and fourteen blocks from the ocean. They created the Greater Beaches Stadium, Inc. on October 7, 1949 in anticipation of the grand opening of Beach Boulevard within two months. Stock was issued at $5 a share. The corporation was capitalized at $25,000. Stockholders included Howard A. Prather, Harry Hatcher, Jr., Herbert A. Shelley, F. A. Griffin, W. D. “Pete” Dickinson, H. B. Bradford, Ira D. Sams, H. A. “Pee Wee” Durden, and Martin G. Williams.[5] Prather was mayor; Sams, who owned a laundry and some apartments, would be. Shelley owned two game sites on the Boardwalk and directed the Beaches Chamber of Commerce. Griffin had his own amusement park on the Boardwalk. Williams and Dickinson owned buildings which housed different concessions. Prather, a pharmacist, owned a drug store and building across the street. He was the president of the corporation; Hatcher, an accountant who also had a Boardwalk business, was vice president. Shelley was secretary. Ownership appears to have been widespread.

By March 2, 1950, construction crews were hustled to the deadline of having the ballpark ready for the March 27th exhibition game between the Roanoke Red Sox and the St. Augustine Saints. The Beaches News & Advertiser reported on November 17, 1950, that the Beaches might get a Florida State League team in 1951. By early February, 1951, the Corporation was trying to sell it to the City of Jacksonville Beach. Although there was opposition, the Corporation prevailed. Many stockholders were also city government officials, a fact which made it easier for the government to buy the assets. Few, if any, made a profit. It was a civic gesture. The corporate owners demonstrated that the ballpark was more than a pipedream and got the city government to agree. [6]

The city government did better. The Chicago Cubs sent three farm teams to use the stadium in 1951. On April 3, 1951, the Greensboro Patriots and the Grand Rapids Jets played an exhibition night game. Tickets cost seventy-five cents for adults and thirty-five cents for children. The Des Moines, Iowa Bruins team arrived in early April for six days. The Rutherford County [Spindale , NC] Owls of the Western Carolina League joined their fellow Cubs’ affiliates. City officials hoped to have two female baseball teams in May. In mid-November, 1951, Mayor Sams, Prather, H. B. Bradford, Harry Hatcher, Jr. met with officials of Florida State League and a committee from St. Augustine with idea of creating teams in both cities. The previous St. Augustine Saints of 1950 had become the Cocoa Indians. For scheduling purposes, the league wanted an even number of teams. In late November, 1951 the city was engaged in “office negotiations with the St Louis Browns in hopes that several of its farm teams would do Spring training in 1952. In August, 1952, Chamber of Commerce and city officials also pursued the possibility of the Boston Braves in establishing a minor league training camp in 1953 even though the Sea Birds were using the Municipal Stadium.” Chamber officials estimated that the Braves’ organization would bring 240 players and 250 scouts, trainers, wives, reporters, and fans to the beaches for five to six weeks and would pump $200,00 into the economy.[7]

Photo

by Don Keller Looking North Along

The Boardwalk

The Jacksonville Beach Sea Birds, a Class D professional

team, began its short life in 1952. The businessmen who owned it hoped that

professional baseball would add still another source of entertainment for

residents and tourists. Many residents loved the game and a few men could also

fulfill their dream of becoming owners. Minor league teams seemed ubiquitous in

Florida, the rest of the United States, and, even, Mexico and the Caribbean.

How could it miss? The team was owned by the Greater Beaches Stadium, Inc.

whose officers were H. A. Prather (President), Harry M. Hatcher, Jr. (Vice

President), and Herbert M. Shelley

(Secretary).[8]

The ball park (known as the Municipal Stadium) was on South Penman south of

Shetter Avenue, a tad more than a mile from the ocean. Although the focus was

Jacksonville Beach, people in other contiguous communities—Ponte Vedra Beach,

Neptune Beach, Atlantic Beach, and Mayport—rooted for the new team.

Source: BAHS Municipal Stadium (1950) with Intracoastal

Waterway in Background

The team would be part of the Florida State League. The

League was founded in 1919, folded in 1928, and restarted in 1936, and

suspended play in 1942-45 because of World War II. It membership fluctuated. In

1952, the teams were the Jacksonville Beach Sea Birds, St. Augustine Saints,

Deland Red Hats, Palatka Azaleas, Daytona Beach Islanders, Cocoa Indians,

Leesburg Packers, Gainesville G-Men, Sanford Seminole Blues, and Orlando

Senators, ten teams in all. The Sea

Birds were the northernmost team, 160 miles from Cocoa, the southernmost.

The owners hired Thadford Leon Treadway, a former New York Giants player who had become a manager of minor league teams, to create the Sea Birds. Red, as he was known, was born on April 28, 1920 on Crabtree Creek near Athalone, North Carolina into a very poor family. In 1932, the family moved to Marion, North Carolina where he got his first shoes because the family fortunes had improved slightly. By age thirteen, in 1934, he was playing semi-pro baseball in the Tri-County Textile League as a pitcher and a catcher. As he told it, he rented a mule for 10 cents to get to his games. The textile mill gave him a dozen pairs of sox which he sold for a penny each so he netted two cents from each trip, not much money even then but something.

Source: Bobby Trump, Sr. Manager-Player

Leon “Red” Treadway

Source: Bobby Trump, Sr. Manager-Player

Leon “Red” Treadway

Treadway’s

skill as a player landed him a professional contract. His play with the Tri-County

Textile League team and the Atlantic Christian College[9]

in batting earned him a spot on the Wilson, North Carolina team, the Tobs

(Tobacconists), in

the Coastal Plains League in 1941. He moved up to the Atlanta Crackers of the

Class AA Southern Association and then to the New York Giants, playing as an

outfielder in 1944 and 1945 during World War II.

Treadway moved down to the Class AAA Newark Bears of the International League in 1946 with the end of the war and the return of veterans who had been Giants,. He left the team before playing against the Montreal Royals which Jackie Robinson had joined that year.[10] In 1948, he starred on the Des Moines, Iowa Bruins in the Class A Western League. He played in the Caribbean League, managing the Panama Refresqueros de Spur Cola. On the Spur Colas were Negro League players Pat Scantlebury and Leon Kellman. This winter league employed both locals and Americans, including future television star Chuck Conners of Cuba’s Almendares Scorpions. Along the way, Treadway and Conners roomed together.[11] In February, 1949, he starred in the first Caribbean World Series, batting .352 and getting the first hit. The teams—Panama, Cuba, Venezuela, Puerto Rico—featured players of different races. In 1951, he worked as a player-manager for the Suffolk, Virgin Goobers in the Class D Virginia League. Eventually, he became a minor league manager-player.

Before creating the Sea Birds, he managed and played for the Suffolk, Virginia Goobers in the Class D Virginia League.[12] There he signed Bobby Trump, the most popular, versatile and colorful Sea Bird.[13] He saw Trump playing high school baseball at Suffolk High as a pitcher and a catcher. Treadway was managing the Suffolk, Virginia professional team in the Virginia League. Suffolk was the home of Planters Peanuts and Treadway and other baseball players worked in the peanut industry as an inspector during the off season. Later, he was able to get jobs in the industry for some Sea Birds jobs when he managed that team. Treadway told the eighteen-year-old Trump on March 4, 1952 to be ready to be transported to Florida by car later that month to begin training. Trump was born on June 19, 1933 in Suffolk, Virginia. Jacksonville, Florida sports columnist Joe Livingston in 1953 said Trump had been courted by the Cleveland Indians organization but Treadway had convinced him to go with the other Virginians.

The collapse of the Virginia League and the Goobers freed Treadway and some other league players to head south to Jacksonville Beach. Experienced players such as player-manager of the Emporia Rebels Hal Martin and player-manager of the Edenton Colonials “Gashouse” Parker and others followed him to Florida.

Treadway and Trump were the only two who would play both the 1952 and 1953 seasons. Minor league players came and went. Some moved up to higher leagues; some quit; some were released; and some were injured. Pay was meager and the season was only five months long. Scrabbling for income for the rest of the year was tiring. Marriage and children encouraged these young men to find steady, better-paying employment. Treadway was the role model for the club. His batting average in 1952 was .357 with 2 home runs, 65 RBIs, the best on the team. In 1953, it was .365 and one home run with 83 RBIs. Trump would be the most versatile and colorful member in those two years.

Of course Treadway recruited more players than he would eventually use on the sixteen-man team. Florida State League rules not only stipulated the number of players on a team roster but also that no more than four (4) could be veterans, that is, had played professional ball for three or more years. Treadway was a player manager so he could only recruit three veterans.[14]

Treadway assembled his team, a mixture of veterans[15] and rookies. He held a tryout camp in early March in conjunction with the Cincinnati Reds.[16] As of the April 14, 1952 season opener, the team was: Lonnie Francis (outfield), Hal Martin (outfield-infield), Harmon Young (3B), Red Treadway (outfield, manager), Wally Nolan (2B), Bill Robertson (C), Tom Mills (P), Eddie Celardo (C), Dave McCrickard (P), Alton Doyle (P), Buddy Spindler (SS), Joe Angel (P), Bill Alexander (P), Joe Johnson (P), Bill Herman (P), Bobby Trump (C), Bob Phillips (P), Ray Mieszkowski (1B), Buster Kinard (outfield), Bill Langston (P), Gas House Parker (1B), and Shorty Long (SS). Langston, Parker, Long were released shortly after the photograph was taken. Some were traded. The players Treadway assembled last year for spring training cost the owners $525 but the owners later sold two for $800. By May 1, 1952, there were 16 on the team.

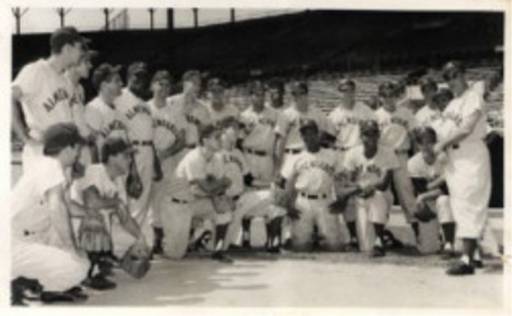

Source:

BAHS Harry Hatcher, Jr. (left) and

Howard Prather (right) with 1952 Team Players

Source:

BAHS Harry Hatcher, Jr. (left) and

Howard Prather (right) with 1952 Team Players

Life was pleasant at the beach. Players roomed and ate in different places in Jacksonville Beach. For example, Bobby Trump and David McCrickard lived above the Bamboo Bar in the heart of downtown which was also the entertainment district. Some lived in the Travelrite Motel very close to the ball park and ate in its restaurant, the Travelrite Drive-In. Others stayed in rooming houses or furnished apartments, both of which were plentiful in the resort community. The Treadways, including their daughter Laura, enjoyed a house in Atlantic Beach. Restaurants often gave them discounts, helping these youngsters who earned very little money in the five months they were in town. They did, of course, enjoy beach life, including the young women who lived or visited at the beach. Konkoleski and some of his teammates in 1954 lived in two-storey frame houses so common in Jacksonville Beach.

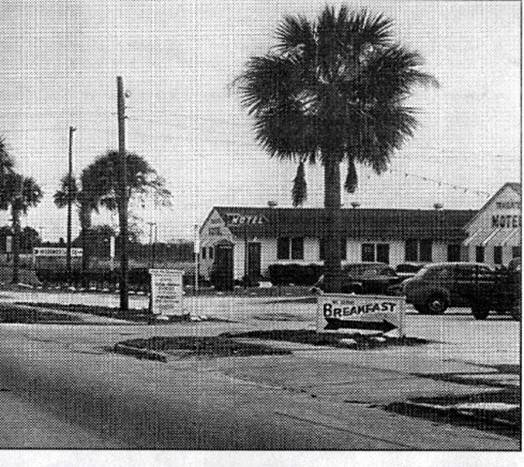

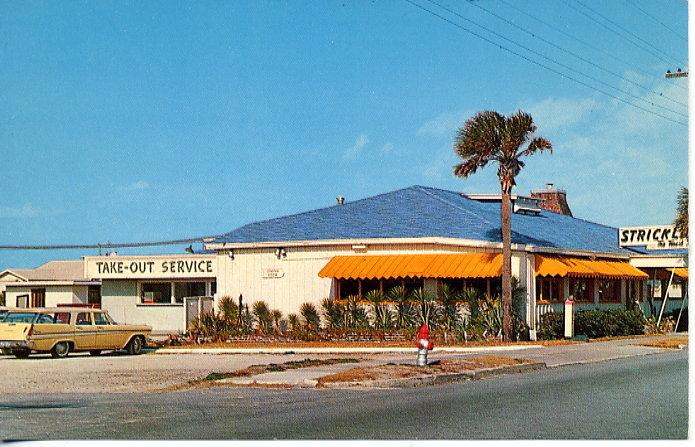

Source:

BAHS Travelrite

Motel and Drive-In on Beach Boulevard

Source:

BAHS Travelrite

Motel and Drive-In on Beach Boulevard

Before the season began, they played an exhibition game

against the Greenville, South Carolina Spinners from the Class B Tri-State

League. The Birds held their own; the game ended 5-5. They competed well

against a higher level team. The season looked promising.[17]

The schedule was grueling. For example, in May the Birds played at home on 15 times in 31 days, going on the road the other nights, traveling as much as 161 miles on two-lane roads.[18] In the first week of the 1952 season, Hal Martin played first base until John Hudzik returned and then moved to left field. Ray Panzo, a rookie from Richmond, was signed to play Shortstop. For their first game, they traveled 159 miles on two lane roads to Cocoa for a Monday night game. Then the team returned home to open the home season against St. Augustine which it beat 25-4 before 1,395 fans. Joe Angel pitched in Cocoa and Tom Mills at home. Harmon Young demonstrated his power by hitting a home run.

In the Cocoa game, Treadway began the search for the perfect batting lineup. He relied upon men he had brought from the Virginia League: Nolan, Treadway, Kinard, Martin, Robertson, and Young, Meiszkowski, Joe Angel, and Francis. As the season progressed, Treadway adjusted the roster. John Hudzik, who played in the Class C Middle-Atlantic League in 1951, joined the Sea Birds the morning of the first game. Bobby Trump, the most versatile of the Sea Birds did well in the first week; he got a single and a double in the Birds’ first home game against Sanford. That week, he went to the plate 20 times and got 8 hits for a .400 average. Two were doubles. He had four RBIs and a stolen base to his credit. During the course of the summer, Trump played shortstop, second base, outfield, and warmed up in the bullpen in case he had to pitch in relief.

By

July 4, 1952, Mills, Angel, and Herman all had thrown no-hitters. Mills threw a

no-hitter against Cocoa for his 19th victory in a 4-0 ballgame.

Thomas “Iron Man” Mills was a 20 year-old, from Geneva, New York who had three

years of professional baseball experience in Lockport, Pennsylvania in the

Class C Middle Atlantic States League.

The

1952 All-Star Game saw Tom Mills (21-4) as the starting pitcher for the

North. Pitcher Dave McCrickard, the only

Bird hurler not to have pitched a no-hitter, was added as a pitcher. The other two Birds on the All-Star team were

Treadway and Buster Kinard.

The Birds were surprisingly successful. The Florida State League split the season in half with the winner of the first half playing the winner of the second half for the pennant. The Birds finished 2nd in the first half of 1952. At the end of the 1952 season during the first playoff game, Bobby Trump demonstrated his amazing versatility in a season-ending game against the Daytona Beach Islanders. For the first seven innings, he played a different position. Had the centerfielder not injured himself while running the bases and Trump had to take his place, the youngster would have completed his grand tour. The game lasted 11 innings; the Birds notched a 7-6 victory. The Birds finished the 1952 season with a 80-56 record, finishing second in the league behind Palatka. In the playoffs, the team finished second.

Treadway had acquired a considerable amount of talent for the expansion team. Tom Mills enjoyed a 27-7 pitching record. Joe Angel won 19 and lost 11. Bill Herman went 16-15. Dave McCrickard won 12 and lost 13. These four were the only one who managed to win ten or more games. The best sluggers were Treadway (.357), followed by Hal Martin (.330), Buster Kinard (.314), and Bill Robertson (.300). Floyd Clift hit .333 but he was not on the roster for the entire season.

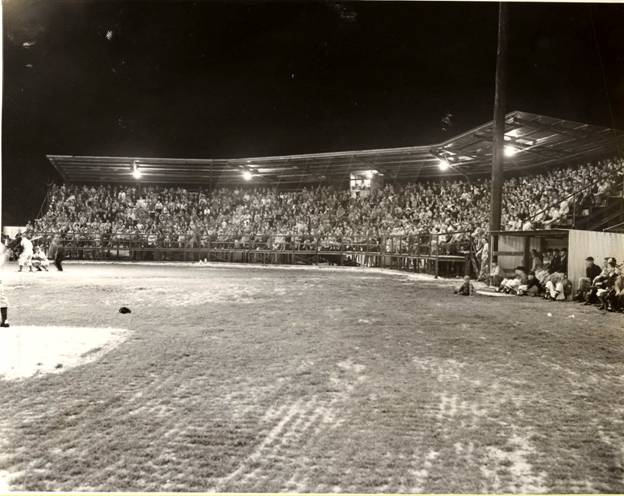

Source: BAHS

Packed Stands ca. 1952

Source: BAHS

Packed Stands ca. 1952

Julian

Jackson and T. F. Cowart, partners in the Jax Meat grocery store chain, bought

the Sea Bird team was purchased in August, 1952. They obtained a five year

lease on the stadium and promised to spend extra money on the team. They

renewed Treadway’s contract with a raise for the 1953 season.

Nevertheless, the Birds had only drawn 23,210 people at home and lost money. Were it not for Jackson and Cowart buying the team and investing $50,000, the team would have closed after the 1952 season. Both loved baseball and attended the home games, sitting behind the dugout, even though they did not live on the beach. Jackson often brought his very young son, dressing him in a Sea Birds uniform.

Treadway created a new team. He signed five rookies and was working on more. He and Young would be the only two “veterans” returning; the League had halved the number allowable. Trump was so good that his return was a cinch. The 1953 Birds would be a quite different but weaker team at the beginning of the season. Florida State League rules in 1953 only allowed two (2) players with three or more year’s experience. Gone were Robertson who went to Class A Williamsport of the Eastern League; Tom Mills who went to Class A Jacksonville but was drafted into the Army; Bill Herman who had to leave because he became a veteran and went to Class B Portsmouth of the Piedmont League; and Buster Kinard who retired.

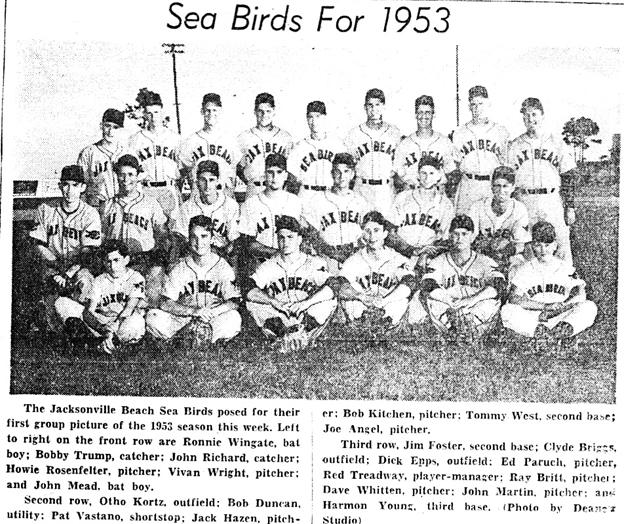

Initially

before the final sorting out, the roster was: Pitchers: Ray Britt, Dave Whitten, John Martin, Ed

Paruch, Joe Angel, Jack Hazen, Bob Kitchen, Howie Rosenfelter, and Vivan

Wright. Catchers: Bobby Trump, John

Richard. Outfielders: Otho Kortz, Red Treadway, Clyde Briggs, and Dick Epps.

Infield: Pat Vastano (SS), Tommy West (2B), Jim Foster (2B) who played in 1949

and 1950 with Gainesville, Harmon Young (3B). Utility: Bob Duncan. There were

two bat boys, Ron Wingate and John Mead.

That

was not the final lineup for the 1953 team. John Hudzik, who had not been on

the team for most of 1952, was signed to play first base. By April 13, the squad had to be down to 20.

By May 3, the team would be pared to 16. Many of the pitchers would be dropped.

New players would be hired. Joe Angel, Ray Britt, and Jack Hazen were the three

best pitchers. Red Foster had played with Gainesville in 1950. Because star

third baseman Young pulled a muscle against Hickory, North Carolina in an

exhibition game, Florida State University graduate student Augie Pompelia

substituted until Harmon returned. Pompelia batted .278 with Class D Statesboro

in 1952. Britt played in 1949 and 1950 with the Gainesville G-Men. Clyde “Apple

Pie” Briggs, who turned 25 during the season, was hired by his fellow North

Carolinian in Virginia. He hit almost .400.[19]

Some of the players were fresh out of local

colleges, a move that would increase the interest of fans. One was the

Pensacola native, Harold “Herky” Payne (pictured below). Quarterback Payne threw a touchdown pass for Tennessee’s score in its

20-14 victory over Texas in the 1951 Cotton Bowl. Tennessee became national

champions for the first time. Famous for

football, he was also the first All-American baseball player in the history of

the University of Tennessee. He earned second-team honors from the American

Baseball Coaches Association after helping the Volunteers reach the 1951

College World Series. The second baseman hit .362 that year, with 17 hits,

three home runs and 12 RBIs. He was drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1952

but did not make the team. So he turned to baseball.

Another was Jack Hazen who pitched 9-1 for the University of Florida in 1952. Paul Florence tried to sign him to a Cincinnati Reds Class B farm team Burlington [Iowa] Flints but Treadway talked him into playing for the Birds. Jack and his brother owned a 1,000 acre farm in Brooker, Florida near Gainesville, a farm that supported four families. Jack did not want to leave his brother in a lurch by going to Iowa. Instead, he stayed in Florida and gave his brother half his baseball salary and his brother gave him half the farm profits. Hazen said Class D Florida State League ball and collegiate ball were similar. Hazen, before July 21, 1953, went on the inactive list because he had to return to his farm.

By the second half of the season, the lineup had changed. Sid Hartfield and Herky Payne were in the outfield. Warren Saye was catching while Trump pitched a 6-5 victory over the Leesburg on “Trump Night,“ the first game of the 2nd half of the season. Fans loved seeing the teenager teach the “older” guys a lesson. Besides, he was such an affable young man.

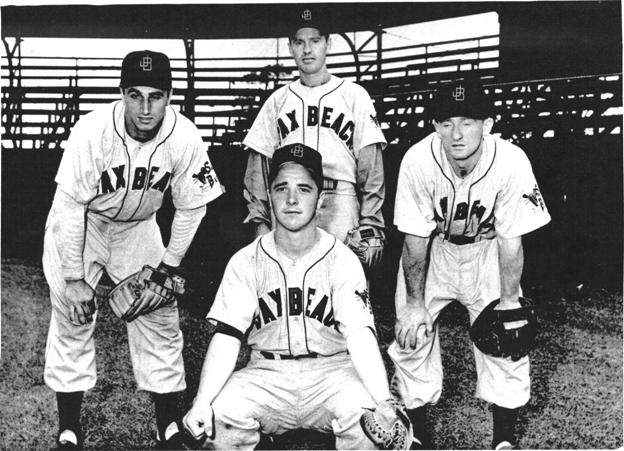

Source:

Bobby Trump, Sr.

Source:

Bobby Trump, Sr.

Squatting:

Bobby Trump (C); Standing: Pat Vastano (SS), Red Treadway (CF and Manager), Jim

(Red) Foster (2B)

In 1953, the Florida State League changed membership.

Neither St. Augustine nor Gainesville sustained teams. The former was too

small; the latter lost to University of Florida sports. The League dropped to

eight teams. Then teams moved. The 1952 champion Palatka Azaleas became the

Lakeland Pilots and the Sanford Seminole Blues became the Sanford Cardinals when

the team became a farm team of the St. Louis Cardinals.

Source: Bobby Trump, Sr.

Source: Bobby Trump, Sr.

Both

in 1952 and 1953, the owners tried a variety of gimmicks in the hope of

attracting more customers and entertaining them with more than baseball.

Various people, including Wilson Wingate, Trump, and other players manned the

Sound Car, which roamed the beaches trying to get people to attend games. The

team hosted the Duval County Beauty Queen contestants to begin the second half

of the 1952 season, and beat the Palatka Azaleas 4-2. The “Sea Bird Follies of 1953” on July 21st saw the players dressed as female

Hawaiian/South Sea Islanders. There was a Cigar Night for men, giving away

cigars and money. Free tickets were dispensed. A Knot-Hole Gang for kids was

created. Players and others performed tricks and stunts before the game to draw

crowds. Al Stracht, the baseball comedian, performed. The son of Bobby Trump,

one of its stars, reminisced about this in 2006.

My father Bobby Trump played baseball for the Seabirds during the 1952-1953 seasons. His starting position for most of his time in Jacksonville was spent behind the plate. He was also called on to pitch on several occasions. On June 23, 1953, he pitched the Seabirds to a 6 to 5 victory for which he received the game ball. That was one of many game balls he would receive throughout his stay with the team. My most memorable story of those days to go along with the many game balls and newspaper clippings I still have telling of his early life heroics was one where, before many of the games started the organization would have the team members perform different promotional stunts. The particular stunt that I recall the most was one in which my father was ask to race a horse from home plate to first base. To this day he will still not tell me whether he won or not.

Bobby

Trump, Sr. reported in 2008 through his son-in-law Rich Hensler that he won the

race.

The 1953 season did not go well even though there were stellar performances. On April 13, 1953, the Birds opened their season in Palatka and returned to the beach the next night to beat the Leesburg Lakers with Britt pitching. Britt was a strong pitcher who could throw no-hitters. In the All-Star game, the Sea Birds placed Joe Angel, Red Foster, Red Treadway, Bob Kitchen, and Bobby Trump. However, the Birds went 68-65 and finished 5th. Treadway went through 13 pitchers and only three had double-digit records: Joe Angel 28-10, Ray Britt 14-7, and Bob Kitchen 10-14. Of the 25 other players who were on the roster that year, only three hit .300 or above: Treadway (.365), Clyde Briggs (.350), and Jim Foster (.301).

Too few attended. The 17,785 patrons were considerably less than the year before. Without paying customers who bought concessions and souvenirs, the team did not generate enough income to cover costs. This was true even though as a percentage of its population base it drew better than Jacksonville but, of course, Jacksonville had a much larger population as well as Hank Aaron. Players at the beach, such as Britt, Trump, and Treadway, and Angel, could play excellent baseball but they could not generate the excitement that Aaron did twenty miles west as he dominated the hitting in the South Atlantic League, playing for the Jacksonville Braves. “Aaron delivered a dominating performance, leading the league in runs (115), hits (208), RBI (125) and batting average (.362). The display of offense captured the league's MVP honor.” Attendance increased dramatically because Jacksonville was integrating its team with Aaron, Felix Mantilla, and Horace Garner and Aaron was so outstanding. African American attendance skyrocket but also those of whites.

One solution to the attendance problem at the beach was to hire some black players but that was not to be. Hank Aaron said that the Birds tried to put black players on the team but the local chamber of commerce said no. Herb Shelley, Secretary of the Chamber, said “No race is involved in it. It’s just that patrons of the team felt they would rather have an all-white team.” City officials and the American Legion also opposed such a move.[20]

By August, owners Jackson and Cowart began talking of shedding their $50,000 losses by pulling out; they demanded concessions from Jacksonville Beach by November 1, 1953. To wit, they wanted a rent-free stadium, utilities, $20,000 worth of advance ticket sales, and 500 season tickets at $40 each ($20,000). Al Burt, a Jacksonville sports writer who was also the team’s scorekeeper, said the biggest problem was attendance and he thought the current attendance was probably the ceiling. An agreement with a major league team might help stabilize the team financially. He thought having a full-time desk man who focused on the problems, as man such as Treadway, might solve the problem. Treadway moved to the Fitzgerald, Georgia team, however.[21] Trump was released on February 24, 1954.[22] The rest either went to another team or gave up the dream. On March 18, 1954, the City of Jacksonville Beach helped the Seabirds Baseball Club by leasing the stadium from April 15th to September 15th for one dollar ($1); agreed to maintain the field and fence; provide police protection; and provide an estimated 65,000 KWH of electricity at the very low rate of two cents a KWH which would total $1,300. The Club would have all rights to advertisements on billboards and the fence. The City, for its part, could use the Stadium when the baseball team had no scheduled game. So, the City had decided to make the 1954 season attractive to owners and a major league team.

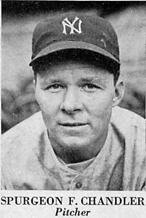

The Cleveland Indian kept the Sea Birds alive for another year as one of its farm teams but changed the personnel of the team, bringing Spurgeon Ferdinand “Spud” Chandler to coach and a new set of players except for Briggs and West. Briggs had hit .350 with 55 RBIs and one home run in 1953; he would hit .355 with 39 RBIs and 3 home runs in 1954. West hit .243 with 6 RBIs in 1953 and improved to .307 with 70 RBIs and a home run in 1954. The Jacksonville Sea Birds Baseball Club was headed by Jackson with Cowart as vice president and Lewis Matlin as business manager.

Chandler

was a well-known in baseball circles and has been nominated for the Baseball

Hall of Fame.[23]

He played 11 years with the New York Yankees (1937-47) with a pitching record

of 109-43 with a 2.83 ERA. He was the only Yankee pitcher to be named the

American League’s Most Valuable Player. He served in WWII. He played in 1946,

going 20-8 with a 2.10 ERA. However, arm surgery failed to solve the problem

that developed and he was released from the Yankees in 1948. He would serve as

a scout and manager for the Cleveland Indians, Yankees, Kansas City Athletics,

and Minnesota Twins. After the Sea Birds stint, Chandler was manager of the

Spartanburg Peaches of the Class B Tri-State League in 1955, and a coach for

the Kansas City Athletics in 1957-1958.[24]  Source: MiLB.com

Source: MiLB.com

Twenty-eight people appeared on

the roster at one time or another. Most of the turnover was in the pitching

staff as Chandler tried to find a cadre of good hurlers and as the Cleveland

Indians gave recruits a tryout. The star pitcher in 1954 was Ray Konkoleski,

the young ace from Adena, Ohio. He far outshone the rest with a 22-6 record and

an ERA of 2.77. He was a star athlete at Adena High School in 1948-52,

lettering in three sports. He played semi-pro baseball with the Dunglen [Ohio]

Miners, UMWA League champions in 1952 and 1953; Bill Mazeroski, the future

Pittsburgh Pirates star, played with him in 1952 as well as on the championship

team of the Times Leader Twilight

League; the team won the league in 1953 as well. Then he was signed by

the Cleveland Indians in 1954 and sent to the Sea Birds. The other successful

pitchers were Dick Hogg who won 12 and lost nine and had an ERA of 4.08 and Joe

Sirois who went 10-4 and had an ERA of

4.36. The other 12 who played at

various times seldom won.[25]

The Sea Bird who succeeded in

baseball was Russ Nixon, who won the 1954 Florida State League batting title.

Before the Sea Birds, he captured the Three-I League hitting crown while

playing for the Keokuk Kernels in 1955. By 1957, he was playing for the

Cleveland Indians. After his playing career, he became a manager for the

Cincinnati Reds, the Atlanta Braves, and some minor league teams.

The home schedule began for the first half on April 12 and ended on June 20 for 34 games. The second half began June 24 and ended August 30 for 35 games. The road schedule began April 13 and ended on June 18 for 35 games and June 21 through August 28 for the 35-game second season. In total, it was supposed to be a 140 game season.

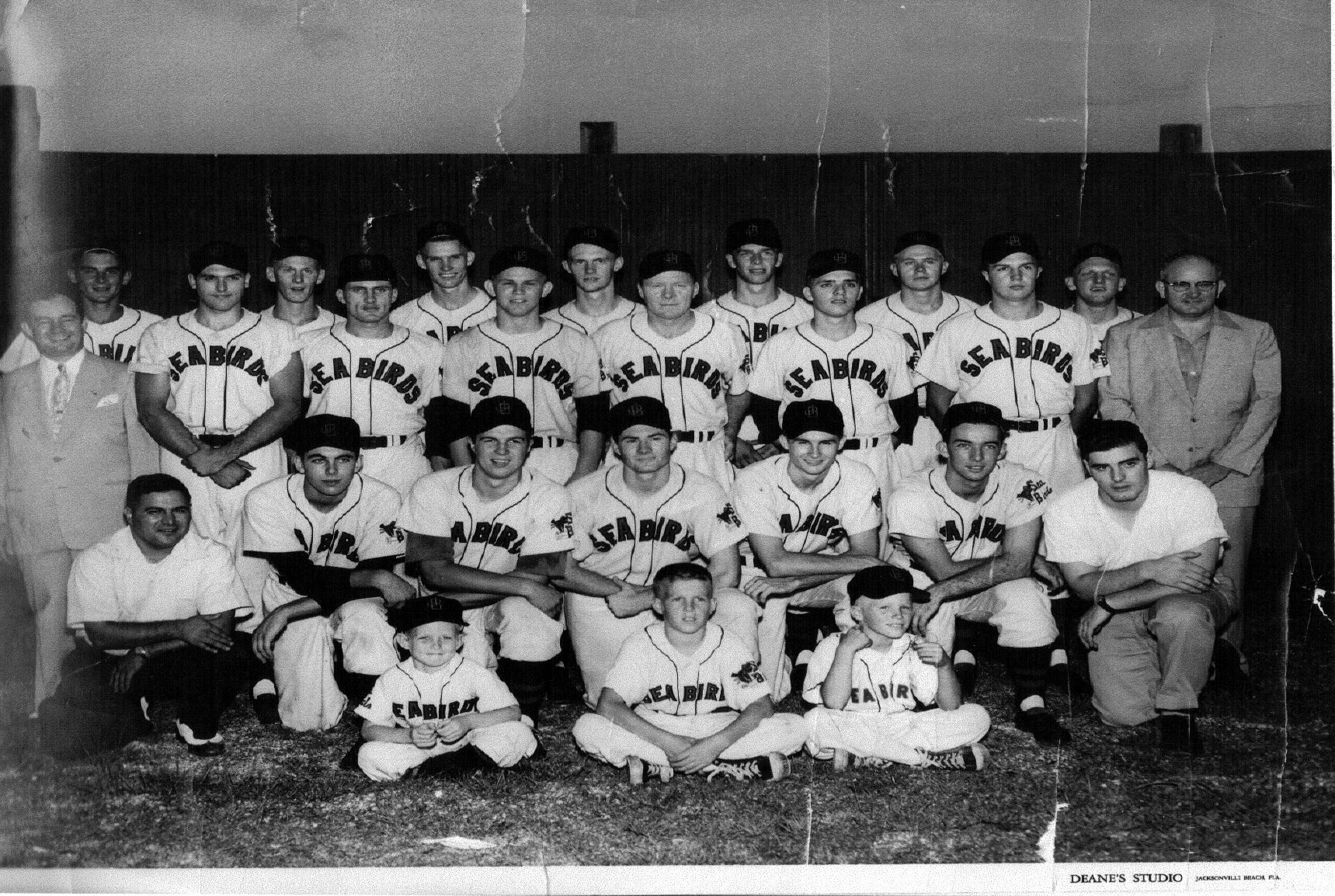

Among the players in the 1954 team photo were the following. The middle bat boy was Frank Chandler, the son of Spurgeon Chandler. Kneeling are Lou Matlin, business manager, unknown player, Roy Nixon, Bill Dashner, Tommy West, Lyn Henry, unknown person. Standing in the first row are Julian Jackson (co-owner), unknown player, Roy Chambers, unknown player, Spud Chandler, Ray Konkoleski, Russ Nixon, and T. F. Cowart (co-owner). In the row, Allen Myers is on the extreme right. People in the photo were identified by Ray Konkoleski and by comparing various photos.

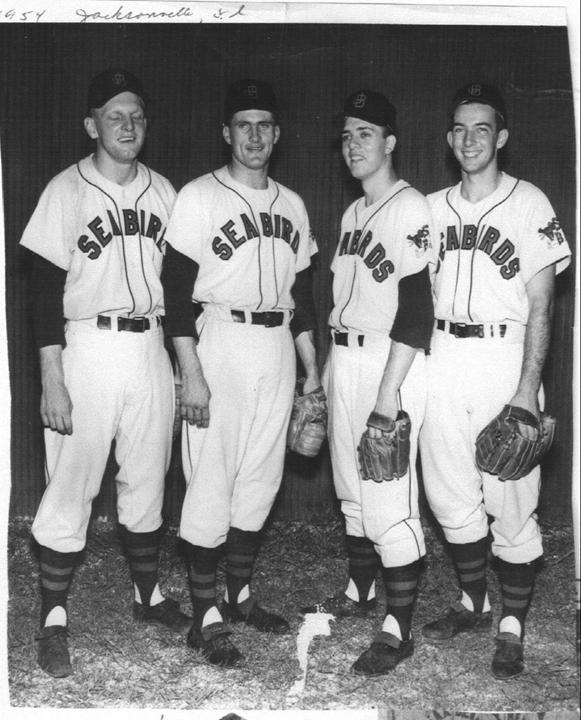

Source: Ray Konkoleski

Source: Ray Konkoleski

L-R: Allen Myers, Roy Chambers, Ray

Konkoleski, Lyn Henry

The final roster included seven

pitchers and ten other players plus Chandler. Throwing right handed were Ray

Konkoleski, Ralph Englert, Zack Gray,Jr., Wilfrid Sirois. Throwing left handed

were Stan Skaza, Dick Hogg, and Gerald Bennett. Jim Mulby and Russ Nixon, the

future major league player, caught. Roy Nixon played first base; Tommy West

held down second, and Lyn Henry third with Allan Meyer at short stop. Roy

Chambers was the center fielder; Billy Joe Dashner the right fielder, and Clyde

Briggs the left fielder. Chandler managed and served as the pitching coach.

Konkoleski remembers his year with Jacksonville Beach fondly. He was given a $1,500 signing bonus collectible at $500 a month. His salary was $175 a month. When the team traveled, the players received $1.75 a day for meals and owner Jackson matched it. Restaurants often gave them a discount. They lived in two-story frame houses, common to the beach, usually renting rooms.

Chandler, like Treadway, was like a father to the players who were, for the most part, considerably younger than he. Both managers were experienced Major League Baseball players and minor league managers/coaches. They were married men with families; most of the players were bachelors. Chandler demanded that they not get sun burned, fining any who did, but they could frequent the Boardwalk and other locales.

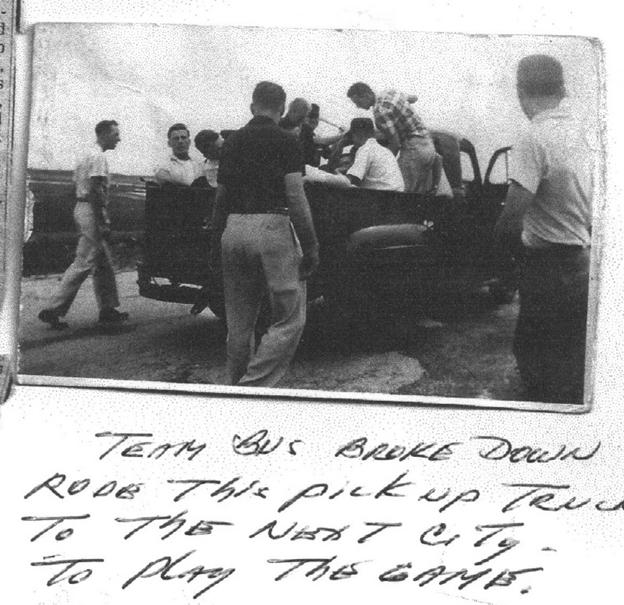

Spring training was in Daytona Beach, home of their arch rivals, the Islanders whose fans harassed the Birds on and off the field. Konkoleski never lost a game against Daytona, giving the Birds great satisfaction. To these young men, being on a team with other like-minded young men, living on a beach, and traveling was as much fun as playing professional baseball. In the early 1950s, when the Unites States was not as prosperous nor as well-organized at it became in the twenty-first century, life held frequent surprises and serendipitous events. Once, when the team bus broke down, the players piled into a pickup truck to get to the game.

Source:

Ray Konkoleski

Source:

Ray Konkoleski

Chandler’s 1954 Sea Birds won the first half

of the season but the

Birds had a 76-63 record (55%) and lost in the league finals, finishing third

in the league. Lakeland won the second half of the season and then defeated the

Birds in the five-game playoffs, three to two. Konkoleski and Russ Nixon could

not win the games by themselves. The Florida State League only had six teams in

1954: Jacksonville Beach Sea Birds, Orlando C.B.s,

Daytona Beach Islanders, Deland Red Hats, Lakeland Pilots, and the Cocoa

Indians so his team had not done as well as the two that Treadway managed.

Attendance had rebounded to 22,660 but still below the 1952 figure of the first

Treadway team. Even the presence of the twin brothers, Roy and Russ Nixon, born

February 19, 1935 in Cleves, Ohio, did not draw the crowds. Roy batted .324,

hit 4 home runs, and had 91 RBIs but Russ batted .387, hit 6 home runs, and had

96 RBIs. He won the Florida State League batting title in 1954 and went on to

became a major league player in Cleveland, Boston, and Minnesota. He would

manage with the Cincinnati Reds in 1982, 1983 and with the Atlanta Braves in

1988, 1989, and 1990.

The Indians abandoned the Birds and the Sea

Bird franchise disappeared. Some men would play elsewhere; some found other

jobs. Both Russ and Roy Nixon moved to better teams, Russ reaching “The

Show.” Ray “Chesty” Konkoleski followed

Chandler to the Spartanburg Class B Peaches. Then Konkoleski moved to the

Fayetteville [NC] Highlanders Class B club and pitched 12-16. He advanced to

the Class AA Mobile Bears in 1957; was drafted; and returned in 1959. Although

he played for the Class A Reading [PA] Indians until 1961, his pitching arm never

recovered so he was released as a player and began managing. Class D baseball gave

young ball players the chance to compete for a few months or years but, of

course, few climbed the ladder to reach the majors.

What happened to the baseball facilities? City Manager Wilson Wingate worked with Joe O'Toole of the Pittsburgh Pirate organization to locate the Pirates’ minor league training facilities in Jacksonville. Beach.[26] The city built four baseball diamonds just south of the Jacksonville Beach baseball stadium. Seventeen teams trained between 1957 and 1961. In 1957, the Beaumont Texas Pirates of the Class B Big State League, the Clinton Iowa Pirates of the Class D Midwest League, the Columbus Ohio Jets of the Class AAA International League, the Grand Forks, North Dakota Chiefs of the Class C Northern League, the Jamestown, New York Falcons of the Class D New York-Pennsylvania League, and the Lincoln, Nebraska Chiefs of the Class A Western League. Clinton, Columbus, Grand Forks, and Lincoln were joined in 1958 by the Salt Lake City, Utah Bees of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League and the San Angelo, Texas Pirates of the Class C Sophomore League. In 1959, Columbus, Grand Forks, Lincoln, Salt Lake City, and San Angelo were joined by the Class D Dubuque, Iowa Pirates of the Midwest League, the Idaho Falls, Idaho Russets of the Class C Pioneer League, the Wilson, North Carolina Tobs of the Class B Carolina League, and the Columbus, Georgia Pirates of the Class A South Atlantic League. Columbus, Grand Forks, Lincoln, Salt Lake City, San Angelo, and Dubuque were joined in 1960 by the Asheville, North Carolina Tourists of the Class A South Atlantic League, the Burlington, Iowa Bees of the Class B Illinois-Iowa-Illinois League, the Hobbs, New Mexico Pirates of the Class D Sophomore League, and the Savannah, Georgia Pirates of the Class A South Atlantic League. In the last year, 1961, only four teams trained there: Asheville, Burlington, Hobbs, and the Batavia, New York Pirates of the Class D New York-Pennsylvania League.

These teams included African American players to the beach. The Beaches were not hospitable to African Americans so there were no facilities available for the black minor league baseball players at the beaches. Wingate’s son, Ron, remembers hearing discussions regarding this problem. Housing was accomplished by farming them out to “The Hill,” a black section of Jacksonville Beach a few blocks east of the station. Strickland’s Restaurant, a very popular eatery more than a mile north, added a back room in which African Americans could eat and be served by fellow African Americans. [27]

Strickland's Restaurant, ca, 1955, Jacksonville Beach, Florida

The Pirates stayed three years and left but the Beaches benefited. The Pirates organization infused money into the local economy while undermining some of the segregation practices as black and white men played together. After they left, the facilities plus some other acreage were converted to a golf course, Wingate Park with two adult softball fields, two T-Ball fields, two little major league” fields, and a girl’s softball field, and a police building.[28]

Why was a community based on entertainment unable to sustain a professional baseball team?

The Beaches permanent population in 1950 was less than 11,000. Daytona Beach, which still has a Florida State League team, has 30,000 inhabitants and no big city nearby. Before television, small towns far from big cities could sustain a team, but the Beaches did not meet these conditions. Even though the Beaches grew in the early fifties, supporting a Class D team was impossible. Jacksonville residents could attend the games of the Class A Jacksonville Tars/Braves;[29] why drive twenty miles to see a lesser team? The Birds could not compete against Hank Aaron in 1953 or the Braves in 1954 which also finished first in the league but came in second in the league finals. Even with Russ Nixon playing very well in 1954, the beach team could not compete against the Braves.

The city fathers, especially the group which built the stadium and attracted the team, may have assumed that baseball games would be an added tourist attraction in addition those on the Boardwalk and the Jacksonville Beach entertainment district. The city fathers depended upon tourist spending because most were in the hospitality business. We now know that a baseball team at the Beaches could not be profitable or draw people to the beach communities. They misjudged business conditions.

Air conditioning in homes kept people inside. The number of air conditioner units, window or central, grew in the early 1950s. In 1950, the nation manufactured 194,000 room air conditioners; in 1955, 1,283,000.[30] The key reason was television. In 1950, 3,875,000 homes had television; by 1955, 30,700,000 did.[31] People chose to watch TV programs, including sports, at home. Minor league teams and leagues were disappearing because of the preference for television and watching major league teams or a higher level minor league team.

The major leagues hurt the minor league teams in two ways. First, they expanded the American and National Leagues by absorbing some of the most important and successful minor league teams. Second, they created a farm club system, spending money to insure that the majors would have the players they wanted. This had the effect of orphaning those teams not connected to a major league club’s system. In short, lower-level professional baseball became serious business. By 1960, there were 135 teams in 20 leagues. By 1963, national attendance had dropped from 42 million to less than 10 million.[32]

The Sea Birds never solved the attendance problem. Giving away tickets, performing stunts, and special events failed to create an audience that could sustain the team. As the chart below demonstrates, the average crowd never approached three hundred and fifty persons.

| Year | Home Games | Attendance | Average |

| 1952 | 70 | 23,210 | 332 |

| 1953 | 70 | 17,785 | 254 |

| 1954 | 70 | 22,660 | 324 |

The

Sea Birds may have been a footnote in professional baseball history but the team

was fun while it lasted. Young men got a chance to see how well they could

compete. Some were able to play for other minor league teams, enjoying the

thrill. Russ Nixon made a successful career in Major League Baseball. Treadway

and Chandler were able to shape and inspire young men. Fans saw some good

players and some great games and have fun. And isn’t that what the sport is

about?

By Don Mabry

Source:

Cubanball.com

Source:

Cubanball.com

Almendares Scorpions

Newspapers:

Beaches

News

Beaches News and Advertiser

Florida Times-Union

Jacksonville Journal

Ocean Beach Reporter

Articles,

Books, Websites:

Aaron, Hank, with Lonnie Wheeler, I Had A Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story. NY: HarperCollins, 1991.

Adelson. Bruce. Brushing Back Jim Crow: The Integration of

Minor-league Baseball in the American South. Charlottesville,

University of Virginia Press, 1999.

baseball-reference.com

“Beach Defeats Palatka, 9 to 6,” Florida Times Union, April 22, 1952.

Bellamy, Robert V.

and Walker, James Robert, “Did Televised Baseball Kill the

"Golden Age" of the Minor Leagues? NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture , - 13:1, Fall

2004, pp. 59-73.

“Birds Take Second Again With 8-0 Win Over Saints”

Jacksonville Journal, May, 1952.

“Blues Conquer Sea-Birds, 3-1,” Florida Times Union, July 22, 1952.

Burt, Al, “Treadway Inks Sea Bird Pact, Begins Winter Player

Drive.” Jacksonville Journal. 1952.

Burt, Al, “Birds Open Playoffs Tonight; Trump Shines as

Beach Wins,” Jacksonville Journal. ca.1953.

Burt, Al,

“Sea Birds Will Face Palatka Nine First,” Jacksonville Journal, April, 1953.

Burt, Al,

“Saturday Special,” Jacksonville Journal,

1953.

Burt, Al, “Future Bright For Bird Rookie, ” Jacksonville

Journal, April, 1952.

Burt, Al, “Trump Twirls Beach Victory.” Jacksonville

Journal, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Ray Britt Becomes 4th Sea Bird To

Enter No Hitter In Book,” Jacksonville Journal, 1953.

Burt, Al. “Birds Open Playoffs Tonight; Trump Shines

as Beach Wins,” Jacksonville Journal,

September, 1952.

Burt, Al, “Power Missing, North Stars Still Edge South Nine,

2-1,” Jacksonville Journal, July, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Saturday Special: Cut, Coax Or Quit,” Jacksonville Journal, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Trump Twirls Beach Triumph Victory,” Jacksonville Journal, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Jax Beach Nine In Pro Debut,” Jacksonville

Journal, April, 1952.

Burt, Al, “Saturday Special:” An Angel Rushes In,” Jacksonville Journal, May, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Sea Birds Will Face Palatka Nine First,” Jacksonville

Journal, April, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Leesburg in Home Season Opener Tuesday Night,” Jacksonville

Journal, April , 1953.

Burt, Al, “Ray Britt Becomes 4th Sea Bird To Enter

No Hitter in Book,” Jacksonville Journal, 1953.

Burt, Al. “Treadway Inks Sea Bird Pact, Begins Winter Player

Drive,” Jacksonville Journal, 1952.

Burt, Al, “Case For

Beach Baseball Rests, and Now Citizens Must Produce, “ , Jacksonville

Journal, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Saturday Special: Birds Take Flight,” Jacksonville Journal, 1953.

Burt, Al, “Birds Win Lidlifter In Second Half, 4-2,” Jacksonville

Journal, July, 1952.

Burt, Al, “Future Bright For Bird Rookie,” Jacksonville Journal, April, 1952.

Burt, Al, “Rookie Hurler Signed with Indians to Get on Team with

Feller,” Jacksonville Journal, 1954.

Campbell,

Gordon. Ninth Series of Famous American

Athletes of Today. Grierson Press, 2007.

Chamber of Commerce Newsletter, 1949-1959.

Chamber of Commerce files, Beaches Area Historical Society.

“Celebrating Sea Bird Victory,” Newspaper

Photo, April, 1952 or 1953. Ray Britt pitched 5-2 victory over Leesburg Lakers.

Crawford, Ray, “Blues Conquer Sea Birds, 9-4,”

Jacksonville Journal, 1952.

Crawford, Ray, “Beach Downs Sanford, 5-0,”

Jacksonville Journal, 1952.

Crawford, Ray, “Kitchen, Trump Lead Birds in 4-1 Triumph

Over Pilots,” Florida Times-Union.

Crawford, Ray, “Jacksonville Beach Tops Orlando Senators, 13

to 2,” Florida Times-Union April, 1953.

Foley, Bill, "Spring Training Dream Endures in N. Florida,

" Florida Times-Union, July 30, 1997.

Friend, Harold, “Spud Chandler: The Commerce

Yankee. Chandler Has the Best Winning Percentage in Baseball History, “

Suite101.com, September 21, 2007. http://major-league-baseball.suite101.com/article.cfm/spud_chandler_the_commerce_yankee.

Greater Beaches Stadium, Inc. stock

certificate.

“HELP SUPPORT THE SEA BIRDS!,” The Beach News, May 1, 1952.

“Herky Payne Signs With Sea Birds.” newspaper photo, 1953.

“Jacksonville Beach Seabirds,” BR

Bullpen, "http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Jacksonville_Beach_Sea_Birds"

Jacobson,

Steve. Carrying Jackie’s Torch: The

Players Who Integrated Baseball—And America. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2007.

“Jax

Beach Council Approves Use of Stadium,” Beach

News-Advertiser (March 18, 1954).

“Joe Angel Hurls a No-Hitter for Jacksonville Beach,

Fla.,” newspaper clipping. April 27,

1952.

Kraus, Rebecca D. Minor League Baseball:

Community Building Through Hometown Sports. New York, Routledge, 2003.

“Lakers Defeat Sea Birds, 5-2,” Florida Times Union,

1953.

Lamb, Chris, "‘I Never Want to Take Another Trip Like This One’: Jackie Robinson’s Journey to Integrate

Baseball,” Journal of Sports History, 24:2 (Summer 1997), 177-191.

Land, Kenneth C., Davis,

Walter R., and Blau, Jennifer R., “Organizing The Boys of Summer: The Evolution

of U.S. Minor League Baseball, 1883-1990,” American Journal

of Sociology, 100:3

(November, 1994), 781-813.

Livingston,

Joe, “Meet the Sea Birds: Philly Writer Stirs Thadford’s Dander,” Jacksonville

Journal, April, 1952.

Livingston, Joe, “Tom Mills’

No-Hitter Birds’ Third This Year,” Jacksonville Journal, July 5, 1952.

Livingston, Joe, Trump Was Drafted As Prep Catcher,”

Jacksonville Journal, 1953.

Livingston, Joe,

“Meet The Birds: “Apple Pie” Briggs Is Man In A Hurry,” Jacksonville Journal.

1953.

Livingston, Joe, “Meet the Sea Birds: Trump Was Drafted as

Prep Catcher,” Jacksonville Journal, 1953.

Livingston, Joe, “Meet The Sea Birds: Philly Writer Stirs

Thadford’s Dander,” Jacksonville Journal, 1952.

Mabry, Donald J., World's Finest Beach . (HTA Press, 2006) at http://tinyurl.com/5kdkb3.

McCann, Mike, “Mike McCann's Minor League Baseball Page,” http://www.geocities.com/big_bunko.

McCarthy, Kevin M. , Baseball

in Florida. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press, 1996.

Madden

,W. C., and Patrick J. Stewart,

The Western League: A Baseball History, 1885 Through

1999. MacFarland. 2002.

Miss Duval County Beauty Pageant program, 1952.

Molony, Joe, “Chesty Ray Rolls On, Gains 11th

Victory For Sea Birds,” Jacksonville

Journal, 1954.

Molony, Joe, “Konkoleski 20-Game Winner, Seems Good Bet for

Majors by ’56 Season,” Jacksonville

Journal, 1954.

Molony, Joe, “Saturday Special: Bright Future for ‘Chesty’,”

Jacksonville Journal, 1954.

Niteowl049,

“Baseball

Notebook: Jim Abbott and Chuck Connors Facts, “ ArmchairGM. http://www.armchairgm.com/Main_Page

Official Notice release notice to Bobby L. Trump, February 24, 1954,

signed by Lewis Matlin, Business

Manager.

“Play-By-Play Detail of Mills’ No-Hitter,” Jacksonville

Journal, July 5, 1952.

Polk’s

City Directory, Jacksonville Beaches, 1954.

“’Red Treadway

Night” Scheduled at Beach As Sea Birds Meet Orlando Club at 8:15,” newspaper

clipping, 1952.

“Robby’s Bat Barks Loud for Sea Birds,” newspaper article, July, 1952.

“Russ Nixon,” http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Russ_Nixon.

“Sanford Cardinals

Defeat Sea Birds by 10-5 Margin,” Florida Times-Union, June 15, 1953.

Sea Birds Game Program, April 19, 1954.

“Sea Birds Bow to Indians in Eleventh Inning, 5-4,” Florida

Times-Union, May, 1952.

“Sea Birds Top Indians, 10-6, Florida Times-Union, July 27,

1953.

“Sea Birds Lose 8 to 7 Tilt When Cards Score in Ninth,” Florida Times-Union, July 18, 1953.

“Seabirds in the ’53 Opener, 8 P.M.—Beaches Stadium,” Ocean Beach

Reporter, April 10, 1953.

“Sea Birds Annihilate Saints But

Drop Opener to Cocoa,” April, 1952.

“Spud Chandler (1907-1990),” New Georgia Encyclopedia, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?path=/SportsRecreation/IndividualandTeamSports/Baseball&id=h-2950.

“Spud Chandler,” BaseballLibrary.com. baseballlibrary.com.

“Spud Chandler,” Gary

Bedingfield’s Baseball in Wartime. http://www.garybed.co.uk/player_biographies/chandler_spud.htm.

2008.

“Spud Chandler,’ http://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Spud_Chandler.

“Spurgeon

Chandler, Obituary, St. Petersburg Times

(FL), January 11, 1990.

Stalder, Dick. “Trump Hurls Sea Birds to 6-5 Decision,” Florida Times-Union, 1953.

Staldler, Dick, “Sea Birds Thump Pilot Club, 13-1,” Florida Times-Union, 1953.

Stalder, Dick, “Islanders Overcome Birds in 7-5 State League

Game,” Florida Times-Union , July,

1953.

Stalder, Dick, “Sea Birds Rally, Down Red Hats,” Florida Times-Union, 1953.

Terwilliger, Wayne, with Nancy Peterson, and Peter Boehm, Terwilliger Bunts One. Globe Pequot, 2006.

The Bird Brain [Vivian Ropon], “For The

Birds,” Column in Sea Bird Program.

Thorn, John, and Palmer, Pete. Total Baseball. NY,

Warner Book, 1989.

Treadway, Leon “Red”, letter to Bobby Trump, March 4, 1952.

Treadway, Red, “Red Treadway Talks Back, Looses Blast at

“Grandstand Managers,’” Jacksonville

Journal, 1953.

Treder, Steve, “ Dig the

1950s,” The Hardball Times, www.hardballtimes.com/main/printarticle/dig_the_1950s/

Tygiel, Jules,

Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie

Robinson and His Legacy. New York, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Weiss,

Bill, & Marshall Wright, “Team # 82--1941 WILSON TOBS (87-30),” TOP 100 TEAMS. Minor League

Baseball,. http://web.minorleaguebaseball.com/

092408