By Donald J. Mabry

Too little is known about the local or micro history of African American residents in the United States. This is certainly true of those who have lived on the “Beaches”—the oceanfront of Jacksonville, Florida.[1] Nor are there substantial collections of original documents or oral histories one can consult. The Rhoda Martin Cultural Heritage Center, opened in 2007, was built to further appreciation of African American history at the Beaches but it has few resources and its office hours are not convenient for many. The much larger Beaches Area Historical Society (BAHS) operates on a shoestring budget and with a lot of volunteer labor. Beaches history lacks many records, especially complete records, or runs of beach newspapers. BAHS, established in 1978, begun collecting them but its collection of materials is spotty; it has the only collection of newspapers published at the beach but no complete runs. My research there has been invaluable but all of it has had to be supplemented by private sources, by census records, published materials, and oral testimony. All of which goes to say that we do not know much about the lives of African Americans at the beaches.

My goal with this essay is to explain what I know and provide some tools for others to do research. The bibliography at the end of the essay will guide the reader to sources. As I go along, I will provide many names of African Americans who have lived at the beaches so they don’t disappear and because knowing them may help future researchers. In addition, photos and map images are provided.

There may have been African Americans as well as whites before the building of the Jacksonville and Atlantic railroad in 1883-85 but there couldn’t have been many. The Palm Valley area (the former Diego Plains) was older but sparsely populated. It was the creation of Pablo (neé Ruby) Beach that brought the people to the area.

African Americans built the railroad and worked on it as section hands and as hostlers. They helped level the sand dunes so dwellings and stores could be built. They worked at the livery stables and the maids in homes and hotels. According to Dianne Hagan, James Dixon, an African American, went to Jacksonville Beach (then Pablo Beach) as a section hand for FEC railroad. Dixon quoted as saying that as many as 200 African American men employed by the big hotels during the “season.” Since most of the original houses (called cottages) were owned by wealthy men from Jacksonville whose primary residence was Jacksonville, African American servants probably went to the beach with their employers. Hagan asserts:

During the early history of the beaches, the McCormick Construction Company employed more African Americans than any other area business. The company built A1A from Jacksonville Beach to St. Augustine and employed many African American workers. The workers earned $1 per day, which was not unusually low in the teens, 1920’s and 1930’s. The McCormicks maintained separate quarters and a commissary for the African Americans employees.

African Americans also worked as domestics and handymen. They worked for the railroad which was built to the beach in 1884. They also were employed by hotels, restaurants and boarding houses. These opportunities for employment are probably a factor in African Americans settling in Jacksonville Beach.

We know a little about who lived in Pablo Beach in 1887 because the historical society has a copy of Richard's Jacksonville Duplex City Directory. Jacksonville: John R. Richards & Co., 1887. It lists 145 persons of whom 33 (22.8%) were identified as African American (colored being the term used). Those identified appear to be heads of household and the occasional single person. So we can’t know who lived in Pablo Beach from Richard’s; in fact, it asserts that there were a thousand people at Pablo Beach but that count has to be exaggerated even for the high season in the summer when the wealthy brought families and servants to live. After all, the one thousand figure would be about seven times the number he actually lists. Later United States Census records do not confirm it.

We can know the names and occupations of the African Americans Richard’s lists but, like the whites, we have to assume that some of them had families living with them. Someone had to stay behind when the wealthy went back to Jacksonville. This table is built from Richard’s.

NAME

OCCUPATION

EMPLOYER

Brackett, William

2nd Cook

Murray Hall Hotel

Brooks, Carrie

Domestic

J. Q. Burbridge

Brown, Jane

nurse

J. M. Barrs

Burrow, Edward

Waiter

Hotel Pablo

Carter, Willis

Hostler

T. McMurray

Collins, William

Hostler

T. McMurray

Columbus, Christopher

Hostler

T. McMurray

Edwards, Henry

Chief Cook

Hotel Pablo

Franklin, James A.

Butler

G. E. Wilson

Gordon, Alice

Cook

John Clark

Gordon, Mary

Domestic

W. A. Gibbons

Hughes, William

Waiter

Hotel Pablo

Jackson, H. Andrew

Hostler

T. McMurray

Johnson, Alice

Laundress

Hotel Pablo

Johnson, Daniel

Hostler

T. McMurray

Lamar, Ellen

Chambermaid

Hotel Pablo

Lockett, Thomas

Servant

F. E. Spinner

Lotry. Annette

Domestic

W. B. Clarkson

Monson, Charles

Porter

W. A. Gibbons

Moses, Holly

Carpenter

Palmer, Henry

Laborer

Porter, John L.

Manager

T. McMurray

Reeves, Emma

Domestic

J. Marvin

Sluman, Annie

Domestic

H. W. Brooks

Smith, Edward

Second Cook

Hotel Pablo

Smith, Hattie

Domestic

G. W. Wilson

Thompson, Nora

Janitress

J & A Bathhouse

Watson, Mary C.

Domestic

C. S. L'Engle

Watson, Mary E.

Domestic

C. S. L'Engle

Watson, William

Porter

C. S. L'Engle

Williams, Delia

Laundress

Williams, Sarah

Domestic

T. McMurray

Williams, Thomas

Drayman

According to Richard’s directory, some lived where they worked; there are no records telling us where the rest lived. Some worked for the two big hotels—Murray Hall Hotel and Hotel Pablo--for Thomas McMurray’s livery stable, or the Jacksonville & Atlantic Railroad. Others worked as servants to wealthy people such as former Treasurer of the United States Francis Spinner who lived in his own tent city and John M. Barrs, a lawyer who was also secretary of the railroad. We know that whites also worked as servants. In the late 19th century, one had to have money to build a summer cottage in the wilderness at least fifteen miles from places to work.

We have records for the men who organized the railroad company and were given thousands of acres of land by the taxpayers, land which they sold to build the little railroad[2] ; after all, as the elite, they left all kinds of records. Newspapers covered what they did. Government forms were created. Some wrote. We have few records, however, for the ordinary people. One exception is the Scull family because William E. and Eleanor K. Scull were among the first settlers because the family helped survey the railroad right of way and Postmistress Eleanor named the settlement Ruby Beach after their daughter. Years later, Eleanor talked to the Federal Writers Project, a New Deal relief program, about their experiences. One can’t do history without records.

We know that Henry M. Flagler hired African Americans to work on his Florida East Coast Railway, bought the J & A, revamped the narrow gauge into standard gauge, and extended the line to the fishing village of Mayport on the south bank of the St Johns River close to the mouth of the river so he import coal. He also built the luxury Continental Hotel and created Atlantic Beach. In both cases, African Americans worked for Flagler and some lived in what became the Donner area of the settlement, west of the Hotel. Some lived in Mayport. Some lived in Pablo Beach. Perhaps there are pay books or some other payroll records that tell us who worked for Flagler at the beaches, when, and want their names were. Such records probably would tell us how much they were paid.

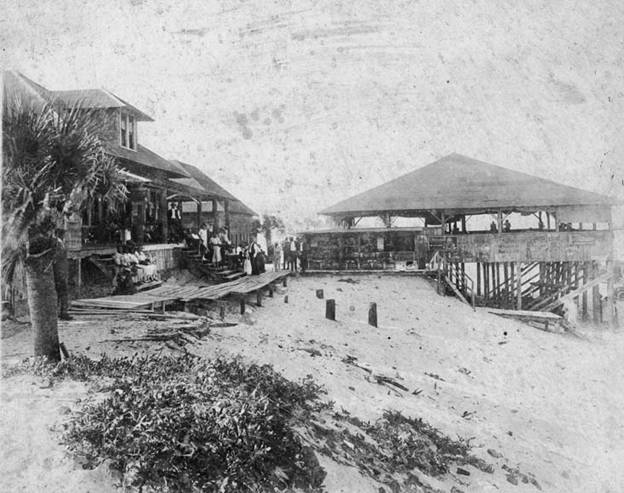

The Florida East Coast Railway created Manhattan Beach for its African American employees. Manhattan Beach, north of Atlantic Beach and south of the jetties, opened with pavilions, cottages, and playgrounds. Some years later, it would be replaced by American Beach in Nassau County to the north.1964 U. S. Geological Survey

Whites and African Americans were not allowed to use the same stretch of ocean beach. The Charter and Ordinances of the City of Pablo Beach (1924) compiled by City Attorney Stanton Walker is typical and explicit. Section 103 said:

It shall be unlawful for any white person or persons to bathe together with any negro person or persons, or for negro person or persons to bathe together with any white person or persons in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean within the limits of the City of Pablo Beach.

The authors of the ordinances believed that Negro genes were much more powerful than white genes for they defined a Negro as any person who had one-eighth or more of Negro blood, that is, if a great grandparent was a Negro (Section 104). Then the person was a Negro for the one-eighth trumps the seven-eighths! Together, according to Section 105, was within 500 feet. Violators could be punished by ninety-days in jail or a one hundred dollar fine or both (Section 105). One hundred dollars would buy 714 quarts of milk in 1924 so the fine was substantial.

Manhattan Beach was provided by Flagler’s Florida East Coast railroad for its African American workers. The Atlantic Beach Corporation acquired it from the FEC and then Harcourt Bull took over. Bull leased land to business people and resisted pressure for years from white to drive African Americns away. Eventually, the state bought the land to make it a state park.

In his letter of J. H. Payne, Atlantic Beach Corporation to FEC vice president J. P. Beckwith. October 24, 1914, Payne wrote to tell Beckwith that the conditions of the pavilion were worse than he had said earlier and that, within the last six weeks, the beach had eroded 12-15 feet and that the north pavilion was now within three feet of the high water mark. He asked the FEC to share the costs of repairing the two pavilions, the bath house, and walkways as well as to improve the site. He estimated the cost would be $925. He remarks that it is not the intention of the Atlantic Beach Corporation as a “colored resort.” As it turned out, he had to write on March, 1915 that the pavilions and bath house needed new foundations and a forty-five foot extension of bulkhead raised the cost to $1,279.24. Payne argued that the repairs would make the site “a creditable colored resort.” The Atlantic Beach Corporation would be bankrupt by 1917 so maybe Payne and associates needed whatever money they could get.

Harcourt Bull ran the affairs of the Atlantic Beach Corporation by 1917 and dealt with Manhattan Beach issues. In his letter to Lucy Bunch, June 6, 1917, he sets conditions for her leasing the Corporation’s property at Manhattan Beach for the 1917 and possible subsequent seasons in order to make it a “first class, respectable Negro resort.” She was to spend at least $200 to repairs the pavilions and bath house as part of the rent, for the property had been neglected. Bull would also get one percent of the gross receipts and the right to inspect her books. He noted that the mortgage on the property was being foreclosed by the Equitable Trust Company of which he was one of the counsels and that he expected to acquire the property because he owned a large majority of the mortgage bounds and would likely buy it. He promised Bunch that he would try to get her a lease for 1918. He also stipulated that no liquor could be sold.

A few years later, the condition of the pavilions and bath house were again an issue as the wind and surf continued to pound away at them. David A. Mayfield, who owned a plumbing and heating company in Jacksonville, wrote to Bull on February 7, 1920 offering to buy the badly damaged pavilions for $60 which he would remove. Bull responded to Mayfield on February 17, 1920 to refuse the offer as being too cheap. He said he was working with “colored people” with the idea of moving the south pavilion further back from the beach and having it repaired so it could continue to be a resort for African Americans.

On December 26, 1922 Bull filed a Notice of Lis Pendens against the Manhattan Beach Corporation in the Circuit Court of Duval County. He wanted to be the first lien on the Manhattan Beach Corporation mortgage foreclosure. The mortgage was for $2,500. The suit named the property as being Lots 1, 2, 3, 4, 11, 12, 13, and 14 in Block 5 and Lots 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 in Block 8. I only have this Notice so I don’t know what happened in this instance but do know that one of Bull’s corporations, the R-C-B-S Corporation, acquired ownership of the Manhattan Beach property.

Bull answered Joseph W. Davin of the Telfair Stockton & Company real estate development firm on November 24, 1932 concerning African Americans at Manhattan Beach about which Davin had inquired in a November 9th letter. Bull said it was the policy of the Corporation (he was president) not to sell to African Americans but leased to them on a short- and long-term but with the proviso that said lease could be revoked if the Corporation sold the entire property to a “developing” company. He then asked if Telfair Stockton & Company’s client wanted such a lease. Since he noted that some lots were owned by African Americans but that they had acquired them before the Atlantic Beach Corporation acquired the area from the Mayport Terminal Company (a Flagler company) many years ago.

The issue of African Americans and Manhattan Beach became more complicated when Edward Ball, the brother-in-law of Alfred I. du Pont. His sister Jessie inherited the Florida du Pont vast business empire when her husband died in 1935 but gave operational control to Ball. Because of these family connections, Ball was a powerful man when William H. Rogers (the R in R-C-B-S) wrote to Bull (the B in R-C-B-S) on January 27, 1933 in regards to Ball’s desires for Manhattan Beach. Rogers copied John T. G. Crawford (the C in R-C-B-S). According to the letter, Ball had just acquired title to the “Manhattan Beach property.” He wanted to buy from R-C-B-S a strip of land 1,000 feet behind his newly-acquired property, a statement that suggests he only bought some land not all of Manhattan Beach. Ball was a racist and he wanted the help of R-C-B-S not only in getting African Americans excluded from Manhattan Beach but also to get them off the oceanfront from the southern limits of Atlantic Beach to the St Johns River. Rogers wanted to meet with Bull, Crawford, and hid law partner C. C. Towers as soon as possible. This was serious.

Marsha Dean Phelts, in her informative folk history, An American Beach for African Americans wrote that the Mack Wilson’s pavilion, the last public facility, was mysteriously destroyed by fire in 1938. She repeats the story of old-timers that the fire was designed to drive African Americans out. She included photos from the Eartha White Collection of the University of North Florida in Jacksonville. The Beaches Area Historical Society also has these and other photos.

Mack Wilson Pavilion Eartha White Collection, University of North Florida.

William Middleton Pavilion Eartha White Collection, University of North Florida.

One report from the 1950s said that Negroes owned beachfront property but that the lack of bulkheads allowed storms to wash it away. Efforts to lease land on the oceanfront had failed.

Manhattan Beach still existed at least until 1964 as shown by this snippet of the U. S. Geological Survey Map of 1964 and revised in 1992 and, for a time at least, was an area where African Americans were allowed to go to the ocean. As a teenager in the 1950s, I rode on the beach to the jetties which channeled the St Johns River into the ocean and saw African Americans on the beach. Eventually, the State of Florida bought the land adjacent to the south of the expanded Navy facility at Mayport and created Hanna State Park, thus swallowing Manhattan Beach.

African Americans used the beach at Jacksonville Beach before 1964 under limited circumstances. Baptisms were one. There was a time when they were allowed to use the ocean on south Jacksonville Beach on Mondays. I don’t remember that being true in 1953 but I was young.

Baptismal service, Jacksonville Beach

Someone interested and patient could plow through the property records of Duval County for the area. Property ownership and transfers are recorded. One would have to discover if the owners were African American or not. Such an approach would discover what happened at Manhattan Beach. Such a study would be a good master’s thesis.

In an earlier essay entitled “WWI Veterans: Jacksonville Beaches & Mayport ,” I identified the men who registered for the Selective Service System (the draft) passed by Congress in May, 1917 and those who served. There were two sources: Raymond H. Banks, “Historical Background of The World War I Draft ,” at http://archives.gov/genealogy/military/ww1/draft-registration/index.html, World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, M1509 and the Military Service Cards found at http://www.floridamemory.com/Collections/WWI/. I list the names of the African Americans who registered so they are not lost to posterity and I note those who served with an asterisk. A disproportionate number of those who serve were African American. At least 106 men in Mayport, Atlantic Beach, Pablo Beach, and Palm Valley registered for the draft, twenty-six of the 106 (24.5%) were African Americans. Who were these black men? We know little about them other than what is in the table below. We do not know why some were chosen. Those who registered for the draft are listed below; those who served in the military are marked with an asterisk.

NAMEBRANCH RANK PLACE VET BIRTH YEAR Aiken, William Army Pvt. 1st Class Mayport * 1895 Barnes, Porter R. Army Pvt. Pablo Beach * 1894 Barnes, Samuel G. Army 1st Sgt. Pablo Beach * 1871 Brooks, Clarence Mayport 1889 Coward, Clarence Army Pvt. Mayport * 1893 Douglass, Archer Palm Valley 1894 Floyd, James L Army Pvt. Mayport * 1895 Hardy, Levi Palm Valley 1880 Jackson, John Army Pvt. 1ST Class Atlantic Beach * 1895 Jackson, Robert Pablo Beach 1880 Jeffcoat, William Howard Army Pvt. Pablo Beach * 1886 Jones, Tobe Pablo Beach 1876 Killin, Alexander Army Pvt. Atlantic Beach * 1897 Kirkland, Alexander Army Pvt. Atlantic Beach * 1893 Knight, Joseph East Mayport 1901 Mincy, Andrew Pablo Beach 1878 Mosly, Edmund Army Pvt. Mayport * 1892 Nicholas, James Mayport 1895 Ruffin, Leroy Mayport 1891 Walker, Jeremiah Army Pvt. Mayport * 1892 Webb, Willie Army Corporal Atlantic Beach * 1894 Wiggins, Albert Mayport 1890 Williams, General Army Private Mayport * 1892 Williams, George Army Private Mayport * 1895 Williams, James Pablo Beach 1879

The WWI Military Service cards give additional information. Those in Florida were Aiken Webster, Samuel Barnes in Madison County, Floyd and George Williams in Mayport, Jackson in Leesburg, Killin in Tampa, Mosly in Orange City, and Walker and George Williams Jacksonville. Porter Barnes was born in Asheville, North Carolina and Kirkland in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Two were born in Georgia: Coward in Westboro and Webb in Coleman. Jeffcoat in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Aiken, Porter Barnes, Coward, Mosly and George Williams served overseas. The cards also give induction location and dates of service.

In 1900, a census taker noted fifty-one African-Americans within eleven families in Pablo Beach, an average family size at the time. There were other African Americans in Atlantic Beach and in Mayport. Since African Americans were forbidden by law and custom from patronizing many white businesses, they created their own just as they had to create other important institutions such as churches, insurance companies, fraternal organizations, and clubs. Maggie Fitzroy wrote in an article about residents reminiscing in February, 2010 and their creating a list from their collective memories:

Completing the history project in time for a January social celebration called "A Night on The Hill," they listed businesses that included two Smith Grocery stores, a drive-in movie, a laundromat, Boston Tea Room, Crow Grocery, Georgia Boy Grill, Leo and Ace Restaurant, Holloway Steak House, Chicken Shack, Blue Moon boarding house, St. Andrew AME Church, 600 Club nightclub, Poor Boy Pool Room, Nelson Hayes Barber Shop, The Waiter Club, Jabo Teenage Club, Evergreen Restaurant, Emma Branch Salon, Mr. Dixon Taylor cleaner and taxes, Beaulia and Cathan Beauty Shop, Marcelee Salon, George and Carrie Redd Barber Shop, Harlem Grill, Tranquil Room, Pearl Cafe, Blue Front Mary Swan, Poor Boy Cab Stand, Charley Thomas Taylor and "Mother Rhoda's House" and the school she founded next door on Shetter Avenue.[3]

By 1905, there were enough African-Americans at the beaches for the founding of the St. Andrews African Methodist Episcopal Church by Mother Rhoda L. Martin in the section known as “The Hill.” This remarkable woman had been born in 1832 and lived until 1948. She founded St. Andrews and began teaching school at age 73. Initially, the church met in her home at the corner of Shetter Avenue and 7th Street South, south of the FEC railroad tracks.

The Jacksonville Beach City Council must have gotten worried about people crossing traditional racial barriers for, in November, 1935, it passed an ordinance requiring residential segregation and job segregation. One wonders what prompted such an action. Government usually pass laws to address an existing problem. Or was it the traditional insecurities that whites in the United States have demonstrated?

The State of Florida counted people in the “5” year between the US Census. In 1925, Jacksonville Beach had 744 people—544 whites, 187 African Americans, and 13 of “other races.” African Americans were 25.1% of the population. Mayport contained 644 people, 430 whites, 214 African Americans (33.2%). Atlantic Beach was too small to be included within the category of “minor civil divisions of the state census. By 1935, Jacksonville Beach had 1,094 people, an increase of 695 since 1930. Of these 797 were white and 297 (27.1%) were African American. Outside the city limits, there were an additional people of whom 359 were white and 43 were African American. Mayport had 511 people; Atlantic Beach had 164. The state census does not provide a breakdown by race. In neither census were the numbers very large. That made no difference.

African-Americans did not get a public school until 1939. White kids were taught in 1887 by Mrs. James E. Dickerson, wife of a storekeeper; by 1903, it was located at 2nd Street South and Orange Avenue (now 2nd Avenue South), located within walking distance of “The Hill.” Segregation meant that the small student population of white and blacks could not be educated together even though to do so made economic sense.

Rhoda Martin

Education was not considered important in Duval County for “white” children and even less for “black” children. In 1900, the Duval County school system spent $12.08 per white child but only $5.47 per "black" child. In the system, 51% of the students were “white.” School lasted only 101 days. Salaries were low but were less than $40 per month for "black" women. School was only for five months.

`In the 1930s, there was a school for African-Americans in East Mayport which had grades 1-6 in one room taught by Miss Short. Allison Thompson in her Shorelines article “Reliving School Day Memories,” of October 7, 1998 wrote of Elizabeth (Williams) Wells who recognized herself and her brother Thomas Williams in a photo of the one-room Mayport School. She was tall, lanky, and wearing a black sweater; her brother, she said, was half-hidden behind a classmate.

Mayport School

In 1939, the Duval County Board of Education began building a four room elementary school for African-Americans (#144) on a two acre lot on the corner of 3rd Avenue South and 10th Street South in Jacksonville Beach. The number of students increased so a building was constructed in 1946. That year, it had 86 students in grades 1-6. The increase in the number of students necessitated the addition of two classrooms and a cafeteria in 1952. By 1956, it had 217 students in grades 1-6 . The Duval County school system operated School #115 for black students in Atlantic Beach in 1946; it had 23 students. Presumably, this school also served Mayport. Nevertheless, there were not many students.

The Second World War (WWII) in which the United States participated from December, 1941 until August, 1945 caused demographic and economic changes to Jacksonville and Duval County prompting the Council of Social Agencies to study the situation of African Americans. On education, its report, Jacksonville Looks at Its Negro Community, found wide discrepancies between the education of whites and blacks. Of the 95 black teachers in 1945-46, 91 of them received $189 a month, the minimum even though they held the Bachelor’s degree and had the maximum experience. By contrast, 71 of 83 white teachers in the same category received $233 a month. Black substitutes got $4 per day whereas white subs got $5 or25% more. This changed at the end of the 1946 year when the Duval County Teachers Association won the suit it had filed in 1941 demanding equalization. Per capita expenditures for white high school students in 1944-45 were $104.53 whereas they were only $70.24 for black high school students. Similarly, for white elementary school students it was $85.15 but $53.08 for black students.

Jacksonville Beach Elementary School # 144 was improved in 1946 when a new building was constructed in 1946 with four classrooms. Student enrollment increased so that two more classrooms and a cafeteria were added in 1952. For the 1955-56 school years, it had had 217 students served by 6 full-time teachers plus an itinerant music teacher. The school was in “The Hill” section but 108 had to be bused. School #115 in Atlantic Beach had closed. Richard H. Cook was the principal. If any child pursued education beyond the sixth grade, it was necessary to be bused twenty-five miles to Stanton High School.

The Beaches population grew by 1945; the Second World War brought a U. S. Navy to Ribault Bay in the tiny fishing village of Mayport and, with it, an influx of people and money. People who worked there lived in different places at the beaches. The Palm Valley precinct had 561 people of whom 406 were classified as white and 155 Negro (27.6%). Mayport had 1,236 of whom 881 were white and 881 were Negro. Neptune Beach had 1,298 whites within its city limits and another 402 persons outside the city limits of whom 391 were white and 11 were black. Atlantic Beach had 956 (921 white, 35 black). Jacksonville Beach had 5,943 people (5274 white, 669 blacks [11.3%] and there were another 779 white outside the city limits.

The Polk City Directories of 1945 and 1948 identified African Americans as “colored” by marking the head of the household with (c), giving us an idea of who lived there. There are some problems with these and other directories. They did not always have the names exactly right or they missed a few people. We cannot know how many people lived at a specific address; usually the person perceived as the head of the household had her/his name listed. Some people operated businesses from their homes. Still, something is better than nothing and the data I have complied from them might give a researcher or someone who is just curious valuable information. Here are the 126 entries for Jacksonville Beach in the 1945 directory, organized by street. Where possible, I have indicated whether the owner was on the premises except for churches and the Jacksonville Beach Elementary School.

Jacksonville Beach 1945

Brown, Fletcher

owner

Lincoln Court 811

Simmons, Benjamin

owner

Lincoln Court 812

Bass, James

rent

Lincoln Court 818

Williams, Sallie E

owner

Lincoln Court 819

Williams, John H.

rent

Lincoln Court 820

Swan, Mary

rent

Shetter 612

Foster, Benjamin

rent

Shetter 614

Longwood, Martha

rent

Shetter 618

Tolson, Catherine

rent

Shetter 714

Little, William

rent

Shetter 718

Toomer, Nathan

owner

Shetter 722

Toney, John

rent

Shetter 726

Smith, Mose

rent

Shetter 732

Jackson, John

rent

Shetter 824

Collins, Charles

owner

1 Av S 503

Nelson, Jacob

owner

1 Av S 504

Poole, George

owner

1 Av S 607

Branch, Roosevelt restaurant

1 Av S 613

Thomas, Estella

rent

1 Av S 615

Cain, Samuel billiards

1 Av S 616

Day, Louise

rent

1 Av S 617

Hughes, Estelle

rent

1 Av S 623

Higginbotham, Gertrude

owner

1 Av S 630

Warden, Thomas

rent

1 Av S 636

Brooks, Floyd

rent

1 Av S 703

Brown, John L

rent

1 Av S 814

Weaver, Ray

owner

1 Av S 815

Dillard, Sylvester

rent

1 Av S 816

Gordon, Lewis

rent

1 Av S 825

Ferrell, Ollie

rent

1 Av S 836

Lane, Frank Rev

rent

1 Av S 911

Dillard, Jesse

rent

1 Av S 912

Linder, Jerry

rent

1 Av S 914

Kirkland, Mattie

rent

1 Av S 915

Davis, Samuel

rent

1 Av S 916

Carter, Walter

rent

1 Av S 919

Dillard, James

rent

1 Av S 920

Dillard, Leice

rent

1 Av S 923

Williams, Ida

rent

1 Av S 924

May, Adler

rent

1 Av S 930

Newsome, Villon

rent

1 Av s 935

Moore, Willard

rent

1 Av S 936

Thomas, Alvin

owner

2 Av S 508

Burroughs, James

rent

2 Av S 509

Burroughs, James

rent

2 Av S 530

McNeal, Robert J

rent

2 Av S 635

Aaron, Hattie

rent

2 Av S 635

Boyton, Arthur

rent

2 Av S 704

Nunnally, Van

rent

2 Av S 708

Jordan, Roxie

rent

2 Av S 716

Glover, Virginia

rent

2 Av S 719

McGahee, Julia

rent

2 Av S 734

Colquitt, Adele

rent

2 Av S 735

Douglas, Keith

rent

2 Av S 826

Leggett, Henry

rent

2 Av S 921

Harris, Claude

owner

2 Av S 922

Robinson, James

rent

2 Av S 923

Sims, Ezekiel

rent

2 Av S 929

Jones, John

rent

2 Av S 931

Sharp, Arrie

rent

2 Av S 935

Jackson, Henry

rent

2 Av S 936

Rice, Ivory

owner

3 Av S 635

Stafford, Sallie

owner

3 Av S 815

Robinson, Theodore

owner

3 Av S 823

Green, Joseph B.

rent

3 Av S 912

Drayton, Ernest

rent

3 Av S 915

Hunter, James P

rent

3 Av S 918

Thomas, Chester

rent

3 Av S 919

Sanctified Baptist Church

3 Av S 921

Allen, Lamar

owner

3 Av S 923

Thomas, Charles T

rent

3 Av S 927

Allen, F. Renaldo

owner

4 Av N 529

King, Gardner

rent

4 Av N 537

Jackson, Henry

rent

4 Av N 603

Waiters Club

4 Av N 637

Branch, Roosevelt

rent

4 Av N 639

First Baptist Church

owner

5 Av S 610

Robinson, Clifford

rent

5 Av S 612

Brooks, Robert

rent

6 St S 32

Rice, Charles

rent

6 St S 35

Martin, Rhoda

rent

6 St S 52

Watford, Roland

owner

6 St S 84

Hayward, Imogene

owner

6 St S 102

Jackson, Addie

rent

6 St S 105

Dixon, Luzene E [James, tailor]

rent

6 St S 106

Simmons, Alphonso O

owner

6 St S 121

Davis, James

rent

6 St S 122

Brewer, Beatrice

rent

6 St S 124

Williams, Frank

rent

6 St S 126

Hollis, Hattie

rent

6 St S 128

Thomas, Claude

rent

6 St S 130

Sneed, Maggie

rent

6 St S 131

Hines, John

rent

6 St S 202

Johnson, Alex

rent

6 St S 204

Hayes, Virginia

rent

6 St S 205

Durham, Mary

rent

6 St S 206

Brown, Hezekiah

rent

6 St S 215

Jones, James

rent

6 St S 221

Williams, Oscar

rent

6 St S 225

Murray, Grace

rent

6 St S 227

Troupe, Elijah

rent

6 St S 229

Wood, Joseph

rent

6 St S 230

Glover, Georgia M Mrs

rent

6 St S 231

Wood, Zack

rent

6 St S 306

Mitchell, Ruby

rent

6 St S 310

Walden, Mamie

rent

6 St S 320

Robinson, Vashti

owner

6 St S 408

St Andrews AME Church

owner

7 St S 200

Anthony, Sandy

rent

9 St S 70

Williams, Essie M

rent

9 St S 80

Vickers, Mary

rent

9 St S 87

Whitten, Curtis

rent

9 St S 102

Jordan, Robert

rent

9 St S 104

Bennefield, Louis

rent

9 St S 106

Hodges, Vassie

rent

9 St S 110

Caine, Walter

owner

9 St S 122

James,Clement

rent

9 St S 126

Terrell, Sandy

owner

9 St S 204

Cain, Samuel

owner

9 St S 210

Hollis, William

rent

9 St S 216

Harris Jack

rent

9 St S 226

Wilcher, Walter

rent

10 St S 71

Isch, John

owner

10 St S 104

Copeland, Caroline Mrs

owner

10 ST s 106

Lawson, William

rent

10 St S 121

Bennett, Trudie

rent

10 St S 125

Small, Samuel

owner

10 St S 132

Jax B Elementary (colored)

10 St S 300

Most lived south of Beach Boulevard in an area known variously as “The Hill” or “Pleasant Hill” and “Pepper Hill” and “Bloody Hill.” The neighborhood was bounded by Beach Boulevard to the north, 3rd Street of state highway A1A the to east , 10th Avenue South to the south, and 12th Street South to West.

The area is flat as a pancake so the “hill” designation is a real puzzle. “Bloody Hill” probably reflects a common view that whites held at the time that “blacks” were inherently violent. Some lived north of Beach Boulevard on 4th Avenue North in the third block west of 3rd Street North. This became a white neighborhood because the Hamby Investment Company wanted to develop all the land westward to Penman Road for white. The story is told in the student paper by Dianne Hagan, “Beginnings of the Black Community in Jacksonville Beach.”1949 U. S. Geological Surver map

Dianne Hagan’s paper was submitted on December 5, 1975 as part of the requirements of a junior-level history course, presumably at the University of North Florida; it is the collection of the Beaches Area Historical Society. She says it is based on oral history and indentifies the interviewees as James Dixon, an 82 year old African American tailor, Deacon Johnny Brown and Blanche Brown, Phil Klein, Jacksonville Beach Fire Chief, a resident of the beaches since 1929, Ed Smith, lumber company owner and memoirist of the beaches, Sue Alexander, retired Fletcher librarian, Dotty Permenter, Rachael Cohen, daughter-in-law of Pritchard, one of the developers of Ponte Vedra Beach, and Stanley Holtsinger. Dixon went to Jacksonville Beach as a section hand for the Florida East Coast railroad. Dixon quoted as saying that as many as 200 African American men employed by the big hotels during the “season.” Those who worked in Mineral City (present-day Ponte Vedra Beach) lived in Jacksonville Beach and traveled the few miles either on the railroad spur or by walking along the beach when the tide was right. Many worked for the B. B. McCormick & Sons Construction Company. McCormick’s headquarters and staging area abutted “The Hill” and the company had quarters and a commissary for its African American workers.

The other African American neighborhood, commonly called “Pistol Hill” was centered on 4th Avenue North. The City of Jacksonville Beach destroyed Pistol Hill, the African American neighborhood north of then Hogan Road but now Beach Boulevard. It contained privately-owned residences, apartments, and the Waiters’ Club, an establishment for Negro men who worked at the Ponte Vedra Inn. When the Hamby Investment Company wanted the land for whites, the City agreed to force the property owners (including the white landlord, I. Silverberg) to sell their houses and property and to accept equivalent property in “The Hill” so that Hamby could develop “Pistol Hill” for whites. The process began in 1942 and lasted into 1948 but most of the work was done by 1946. Part of the time was spent in improving “The Hill” with a Negro Health Clinic, a recreation center, and paved streets. Land was purchased and white residents near “The Hill” petitioned the City not to let African Americans move too close to their neighborhood. On January 21, 1946, the City Council accepted the estimate of $1,934.10 to extend fire protection in the Negro section.

Then the actual moving process began. On June 17, 1946, the Council agreed to pay $4,750 to the Woods-Hopkins Construction Company to move 11 dwellings, two garages, and one garage apartment. Over a year later on November 3, 1947, the Council began discussion of moving Waiters Club but then decided on June 28, 1948 to remove it. It was sold on July 12, 1948.

We know the names of some of the people (see list below) but we do not know what the people forced out of their homes thought except it is hard to imagine any citizen loving being evicted from his/her home. Perhaps letters or diaries written by the affected exist. Without such materials, history cannot be written. History is based on concrete events which we know from documents created by the participant or participants. Documents created by non-participants are hearsay; those created decades later are dubious at best.

Allen, F. Renaldo

owner

4 Av N 529

King, Gardner

rent

4 Av N 537

Jackson, Henry

rent

4 Av N 603

Waiters Club

4 Av N 637

Branch, Roosevelt

rent

4 Av N 639

African-Americans made progress in Atlantic Beach. Steve Piscitelli in his “Donner Subdivision: The Rhythms of a Community sketches the history of the Donner neighborhood in Atlantic Beach. In 1946, the Donner subdivision grew just off Mayport Road (see map below). The subdivision was platted in 1921 and replatted in 1946 by E. H. Donner of Jacksonville Beach. He was a European-American real estate developer who saw the opportunity to earn a profit. The land sold for about $50 an acre but had no public utilities. Donner deeded a lot for a playground in 1948. The people who lived there created businesses. The Palmetto Garden was a restaurant, dance hall, and motel for "blacks." There was also the Bluebird Nightclub. Tony’s Seafood Shack served food but also had rooms on the second floor. Since motels and restaurants were segregated, these businesses provided a real service. A list taken from the Polk City Directory of 1945 shows that home ownership was very high among African Americans. (see below). Because the Donner subdivision was two and one-half miles from the white settlements of Atlantic Beach, the neighborhood had been able to grow too large to move had the whites coveted their land. A Negro Chamber of Commerce was formed to promote business. However, there were no public utilities when the area was being settled and they were slow in being installed. But the Donner Subdivision provided a community for some of the Beaches’ people. The Duval County school system constructed a school in 1939

1945

Status

Street

Houston, Robert

tenant

Donner Rd

Jackson, Anderson

owner

Donner Rd

Peterson, Edward

owner

Donner Rd

Benton, Barney

owner

Donner Rd

Dove, Jafford

owner

Donner Rd

FIitzpatrick, John

tenant

Mayport Rd

Dixon, Dora

owner

Mayport Rd

Koonce, Lex

owner

Mayport Rd

Wilson, Jesse

tenant

Mayport Rd

Stanley, Julius

owner

Mayport Rd

Johnson, Richard

tenant

Mayport Rd

Francis, Maggie

owner

Mayport Rd

Brown, Charles

owner

Mayport Rd

George, Robert

owner

Mayport Rd

Brown, Henry

owner

Mayport Rd

Howell, Julius

owner

Mayport Rd

Howell, Maseo

owner

Mayport Rd

Upchurch, Fister

tenant

Mayport Rd

Powell, Earl

tenant

Mayport Rd

Mills, Robert B

tenant

Mayport Rd

Warren, Norris

owner

Mayport Rd

Stuart, Robert

owner

Mayport Rd

Kennedy, Joseph

owner

Mayport Rd

Friendship Baptist Church

Mayport Rd

Liptrot, Jesse

owner

Mayport Rd

Christopher, Charles

tenant

Mayport Rd

Morgan, Grant

owner

Mayport Rd

Smith, William

tenant

Mayport RdDonner Subdivision and Mayport Road, 1949

This 1949 U.S. Geological Survey map shows most of Atlantic Beach and its population distribution. The tiny squares represent buildings, usually houses. One can see the Atlantic Beach Hotel and its pier on the middle-left side. The African American population lived in the Donner subdivision and on Mayport Road.

Racial segregation damaged all peoples, of course, since it was anti-free enterprise as well as fairness but it hurt African-Americans more than other groups. Education made little difference. Of the 95 African American teachers in Duval County in 1945-46, 91 of them “holding the Bachelor’s degree and having maximum experience” received $189 a month, the minimum. By contrast, 71 of 83 white teachers in the same category received $233 a month, 23.8% more. African American substitute teachers earned $4 a day whereas white substitute teachers earned $5 a day, a 25% difference. The African-American schools in the county also got left-over textbooks. Between high school and college, I worked a summer job for the Coca-Cola Company in Jacksonville and saw this disparity when delivering machines to public schools in Duval County. I also learned that African Americans and summer help were only to get minimum wage no matter how competent or how much seniority the employee had.

No wonder that African-Americans began suing for equal treatment after the Second World War; after all they had sacrificed, bled, and died in a war against German and Japanese racism. There were many successful lawsuits but the one that shook the nation was Brown v. Topeka Board of Education in 1954 which ruled that segregation was inherently unequal and, therefore, unconstitutional. At Fletcher Junior-Senior High School, one heard mutterings that African-Americans would be killed and stuffed in lockers if they tried to integrate the school. The “perfect” world was threatened. It was not the case that the “whites” would not accept another race or a mixed-race person. After all, there were students of Asian ancestry as well as people who were part American Indian. Segregation was keeping "blacks," African Americans, in "their place," a place to which no Fletcher student aspired. Nothing happened for years in terms of school integration but the civil rights movement picked up momentum in the early 1960s.

By 1948, the African American population in “The Hill” neighborhood increased beyond the absorption of “Pistol Hill” as had its small business community. The beaches and the Mayport Navy installation grew because of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War but Jacksonville Beach had also improved the infrastructure of “The Hill.” On April 3, 1944, Councilman B. B. McCormick proposed that the City pave two through streets in “The Hill” neighborhood; the bill carried on September 18th. One of the streets was 9th Street South which eventually dead ended at 16th Avenue South. On April 21, 1946, the city manager was authorized to extend the sewer line in the Hill and extend light and water utilities to the “Pistol Hill” transplant site. Then, on February 17, 1947 officials proposed paving the streets in “The Hill.” People demand goods and services so entrepreneurs opened hair care establishments, restaurants, groceries, laundries, and so forth. More churches were created. H. A. Prather, a prominent white businessman, built apartments in the neighborhood. The Polk directory of 1948 is illustrative. In comparing the 1945 with the 1948 data one sees the same surname but a different first name. Why is unclear. The 1948 showed vacancies as well.

1948

Tenancy

Street

Vacant

Lincoln Court 807

Brown, Fletcher

owner

Lincoln Court 811

Simmons, Benjamin

owner

Lincoln Court 812

Williams, Sallie E Mrs

rent

Lincoln Court 817

Butts, Robert

rent

Lincoln Court 818

Williams, John H.

rent

Lincoln Court 820

Robinson, Clifford restaurant

rent

Shetter 612

Foster, Benjamin

rent

Shetter 614

McIntyre, Ruby Mrs

owner

Shetter 618

Davis, Willie M Mrs

rent

Shetter 618 rear

Little, William

rent

Shetter 718

Toomer, Nathan

owner

Shetter 722

Smith, Mose

rent

Shetter 732

Johnson, James

rent

Shetter 736

Bright, Isadore

rent

Shetter 816

Jackson, John

rent

Shetter 824

Gilbert, William

rent

Shetter 912

Armprester, Lillie M Mrs

owner

Shetter 914

McDonald, George

owner

Shetter 916

Howard, Flax Rev

rent

1 Av S 503

Nelson, Jacob

rent

1 Av S 504

Heyward, James

rent

1 Av S 507

Heyward, Katherine Beauty Shop

rent

1 Av S 507

Poole, George

rent

1 Ave S 611

Williams, Ernest

rent

1 Av S 613

Thomas, Estella Mrs

rent

1 Av S 615

King, Pearl Mrs. grocery

rent

1 Av S 616

Day, Louise

rent

1 Av S 617

King, Pearl Mrs. Restaurant

rent

1 Av S 618

Toomer, Joseph . barber

rent

1 Av S 625

Kites, Earl restaurant

rent

1 Av S 627

Branch, Emma Mrs.

rent

1 Av S 629

Goodwin, Rupert A

rent

1 Av S 630

Warden, Thomas

rent

1 Av S 636

Threats, Alton

rent

1 Av S 637

Collier, Eugene

rent

1 Av S 703

Sullivan, Eugene

rent

1 Av S 794

Brown, John L

rent

1 Av S 814

Weaver, Ray

owner

1 Av S 815

Batton, Susie Mrs.

rent

1 Av S 816

Smith, Roy grocery

rent

1 Av S 825

McLendon, Leo

rent

1 Av S 827

Brown, Jack

rent

1 Av S 829

Gordon, Lewis

rent

1 Av S 831

Ferrell, Ollie

rent

1 Av S 836

Lane, Frank Rev

rent

1 Av S 911

Dillard, Annie B. Mrs.

rent

1 Av S 912

Kirkland, Mattie Mrs.

rent

1 Av S 915

Davis, Ollie M Mrs.

rent

1 Av S 916

Saller [Salter] , Leon

rent

1 Av S 919

Davis, James

rent

1 Av S 920

Young, Maggie

rent

1 Av S 923

Williams, Ida Mrs.

rent

1 Av S 924

Dillard, Lois Mrs.

rent

1 Av S 930

Newsome, Guy Villon

rent

1 Av s 935

Moore, Willard

rent

1 Av S 936

Thomas, Bessie Mrs.

owner

2 Av S 508

James, Claremont

rent

2 Av S 509

Coleman, Henry

rent

2 Av S 610

Donaldson, Caesar

rent

2 Av S 612

Williams, Oscar

owner

2 Av S 614

Nunnally, Van

rent

2 Av S 708

Peoples, James

rent

2 Av S 716

Savage, Luventon

rent

2 Av S 717

vacant

2 Av S 719

Chaney, William

rent

2 Av S 720

Jones, John

rent

2 Av S 731

Peoples, James

rent

2 Av S 734

Leverett, Janie M Mrs.

rent

2 Av S 738

Simmons, Wilbert

rent

2 Av S 911

Harris, Claude

owner

2 Av S 922

Sims, Ezekiel

rent

2 Av S 929

Sharp, Arrie [Ivory]

rent

2 Av S 935

Jackson, Henry

rent

2 Av S 936

Galloway, Lottie

rent

3 Av S 635

Prather Apartments

3 Av S 700-712

Unit 1

Hampton, Gladys

Apt 1

Harrison, Proffit

Apt 2

Lawson, William

Apt 3

Perry, Nellie B

Apt 4

Ruff, Dorothy

Apt 5

Robinson, William

Apt 6

Lewis, Samel

Apt 7

Powell, Jesse J

Apt 8

Unit 2

Longwoods, Martha Mrs.

Apt 1

Brown, Frank

Apt 2

Moore, Thelma Mrs.

Apt 3

James, Hutchie

Apt 4

Green, Joseph B

Apt 5

Rountree, Macie

Apt 6

Robinson, Raymond

Apt 7

Unit 3

Copeland, Ulysses

Apt 1

Smith, Edith Mrs.

Apt 2

Unit 4

Hagans, Dory

Apt 1

Weaver, William

Apt 2

Burke, Thomas

Apt 3

Banks, William

Apt 4

Burroughs, James B

Apt 5

Ikry, Hilliard

Apt 6

Benson, James

Apt 7

Second Baptist Church

corner 8th S

First Baptist Church

3 Av S 800

Stafford, Sallie Mrs.

owner

3 Av S 815

Rice, Ivory

3 Av S 820

under construction

3 Av S 821

Robinson, Theodore

owner

3 Av S 823

Kirkland, Leander

owner

3 Av S 911

Collins, Nellie Mrs.

rent

3 Av S 912

Drayton, Ernest

rent

3 Av S 915

Bennett, Robert L

rent

3 Av S 916

Refoe, Charles

rent

3 Av S 918

Refoe, Charles

rent

3 Av S 918

Allen, Lamar

owner

3 Av S 923

Thomas, Charles T Rev

rent

3 Av S 927

Church of God by Faith

3 Ave S 931

Allen, Lottie Mrs.

rent

4 Av S 412

Williams, Robert

rent

4 Av s 737

Gillmore, Stella Mrs.

rent

4 Av S 808

Edwards, Matilda Mrs.

owner

4 Av S 826

Smith, Robert J

owner

4 Av S 830

Simmons, Lillian Mrs.

rent

4 Av S 830 rear

Waller, James

rent

4 Av S 904

Harvey, Joseph

rent

4 Ave S 908

Bennett, Fulcher

rent

4 Av S 912

Miles, Henry

rent

4 Av S 914

Bell, Simeon

rent

4 Av S 916

Ellis, Nathan

rent

4 Av S 985

Vickers, Charles V

rent

5 Av S 601

Robinson, Clifford

rent

5 Av S 612

Jackson, Celie

rent

6 St S 32

vacant

6 St S 35

Gatsin, Richard

rent

6 St S 51

Martin, Carrie M

owner

6 St S 52

Davis Evergreen Restaurant

6 St S 74

Watford, Sarah Mrs.

owner

6 St S 84

Gilford, Julius [white]

rent

6 St S 115

Jackson, Addie Mrs

rent

6 St S 117

Hayward, Lillie

owner

6 St S 118

Dixon, Luzene E clothes clean

rent

6 St S 120

Simmons, Alphonso O

owner

6 St S 121

Hartsfield, Bernice Mrs.

rent

6 St S 122

Brewer, Beatrice Mrs.

rent

6 St S 124

Williams, Frank

rent

6 St S 126

Hollis, Hattie Mrs.

rent

6 St S 128

Sneed, Maggie Mrs.

rent

6 St S 129

vacant

Burroughs, Susie Mrs.

rent

6 St S 205

Murray, Grace M Mrs.

rent

6 St S 211

vacant

rent

6 St S 212 a

Caine, Isaiah

rent

6 St S 212 b

Bell, Henry

rent

6 St S 215

Coleman, James

rent

6 St S 221

Williams, Bonnie

rent

6 St S 225

Josey, William

rent

6 St S 227

Brown, Hezekiah

rent

6 St S 229

Day, Ellis

rent

6 St S 230

Glover, Georgia M Mrs.

rent

6 St S 231

vacant

6 St S 304

vacant

6 St S 306

vacant

6 St S 308

Walden, Mamie Mrs.

owner

6 St S 332

Robinson, Vashti

owner

6 St S 408

St Andrews AME Church

owner

7 St S 200

Jackson, Ethel

rent

8 St S 35

Harris, Quitman

owner

8 St S 52

Allen, Lottie Mrs.

rent

8 St S 420

Smith, Edward

rent

9 St S 70

Jackson, Walter

rent

9 St S 80

Kirkland, Ralph

rent

9 St S 84

Vickers, Mary Mrs.

rent

9 St S 87

Coleman, Edward

rent

9 St S 102

Russell, Charles

rent

9 St S 104

Taylor, June

rent

9 St S 106

Williams, John W

rent

9 St S 108

Hollis, Alice Mrs.

rent

9 St S 110

Caine, Walter

owner

9 St S 122

Correlus, Golden

rent

9 St S 126

Moore, Henry

rent

9 St S 130

Terrell, Sandy

owner

9 St S 204

Kirkland, Gus

rent

9 St S 205

Cross, Jesse J

rent

9 St S 205 rear

Cain, Samuel

owner

9 St S 210

Warren, Preston

rent

9 St S 210

Jackson, Curtis

rent

9 St S 216

Bass, James

rent

9 St S 226

Shafter, Leroy

rent

9 St S 411

Verner, James

rent

10 St S 71

Copeland, Caroline Mrs.

owner

10 St S 106

vacant

10 St S 106 rear

Isaiah, John

rent

10 St S 110

Hilton, Mamie Mrs.

rent

10 St S 120

Hughes, Stella Mrs.

owner

10 St S 121

Bennett, Trudie

rent

10 St S 125

Small, Samuel

owner

10 St S 132

Kirkland, Lee

owner

10 St S 200

Jax Bch Elementary colored

10 St S 300

McNeill, Robert Jaboe

owner

10 St S 400

Graham, Oscar

rent

Beach Blvd sw of Penman

Rountree, English

rent

Beach Blvd sw of Penman

The Atlantic Beach data for 1948 showed population growth but it also showed five women living in the white section. There were live-in servants no doubt. The percentage of ownership was very high.

1948

Tenancy

Street

Williams, Anna L

Gaines servant

Beach Av 697 rear

Cuthbert, Letha

Blondheim servant

Beach Av 1174 rear

Simmons, Willie M

Rosborough servant

Beach Ave 1433 rear

Muller, Alberta

Tucker servant

Beach Ave 1451 rear

Anderson, Katie M. Mrs.

Kavanaugh servant

Beach Av 1689 rear

Johnson, Minnie L Mrs

rent

Donner Rd

Jackson, Anderson

owner

Donner Rd

Stewart, Robert Jr

owner

Donner Rd

Benton, Bonnie

owner

Donner Rd

Dove, Jafford

owner

Donner Rd

Williams, George

owner

Donner Rd

Brown, Thomas

owner

Dudley St

Griffin, Ollie Mrs.

owner

Dudley St

Hicks, Albert

rent

Dudley St

Howell, Julius

owner

Dudley St

Howell, Maseo

owner

Dudley St

Jenny, Ruby Mrs.

owner

Dudley St

Pierce, Roberta Mrs.

rent

Dudley St

Stewart, Robert

owner

Dudley St

Davis, Ernest

owner

Mayport Rd

Wade, Frank

owner

Mayport Rd

Hand, Charles D

owner

Mayport Rd

Scott, Allen L Rev

rent

Mayport Rd

Stanley, Julius

owner

Mayport Rd

Wade, John H

owner

Mayport Rd

Friendship Baptist Ch

owner

Mayport Rd

George, Robert

owner

Robert St

Holmes, James

owner

Robert St

Liptrot, Jesse

owner

Robert St

One solution to the attendance problem at the beach was to hire some African American players but that was not to be. Hank Aaron said that the Birds tried to put African American players on the team but the local chamber of commerce said no. Herb Shelley, Secretary of the Chamber, said “No race is involved in it. It’s just that patrons of the team felt they would rather have an all-white team.” City officials and the American Legion also opposed such a move.[4]

What happened to the baseball facilities? City Manager Wilson Wingate worked with Joe O'Toole of the Pittsburgh Pirate organization to locate the Pirates’ minor league training facilities in Jacksonville. Beach.[5] The city built four baseball diamonds just south of the Jacksonville Beach baseball stadium. Seventeen teams trained between 1957 and 1961. In 1957, the Beaumont Texas Pirates of the Class B Big State League, the Clinton Iowa Pirates of the Class D Midwest League, the Columbus Ohio Jets of the Class AAA International League, the Grand Forks, North Dakota Chiefs of the Class C Northern League, the Jamestown, New York Falcons of the Class D New York-Pennsylvania League, and the Lincoln, Nebraska Chiefs of the Class A Western League. Clinton, Columbus, Grand Forks, and Lincoln were joined in 1958 by the Salt Lake City, Utah Bees of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League and the San Angelo, Texas Pirates of the Class C Sophomore League. In 1959, Columbus, Grand Forks, Lincoln, Salt Lake City, and San Angelo were joined by the Class D Dubuque, Iowa Pirates of the Midwest League, the Idaho Falls, Idaho Russets of the Class C Pioneer League, the Wilson, North Carolina Tobs of the Class B Carolina League, and the Columbus, Georgia Pirates of the Class A South Atlantic League. Columbus, Grand Forks, Lincoln, Salt Lake City, San Angelo, and Dubuque were joined in 1960 by the Asheville, North Carolina Tourists of the Class A South Atlantic League, the Burlington, Iowa Bees of the Class B Illinois-Iowa-Illinois League, the Hobbs, New Mexico Pirates of the Class D Sophomore League, and the Savannah, Georgia Pirates of the Class A South Atlantic League. In the last year, 1961, only four teams trained there: Asheville, Burlington, Hobbs, and the Batavia, New York Pirates of the Class D New York-Pennsylvania League.

These teams included African American players to the beach. The Beaches were not hospitable to African Americans so there were no facilities available for the black minor league baseball players at the beaches. Wingate’s son, Ron, remembers hearing discussions regarding this problem. Housing was accomplished by farming them out to “The Hill,” an African American section of Jacksonville Beach a few blocks east of the station. Strickland’s Restaurant, a very popular eatery more than a mile north, added a back room in which African Americans could eat and be served by fellow African Americans.[6]

In my very lengthy essay, Carnival on the Boardwalk, I told the story of anti-black efforts at the beaches led by a Jacksonville Beach city councilman. When an uproar occurred in 1960, other city councilmen and beach leaders disavowed the Organization for American Rights, as the organization called itself. Local African Americans must have wondered about this. On April 27, 1958, conservative terrorists bombed the James Weldon Junior High School, a Negro school in Jacksonville, and a synagogue and Jewish community center. There was only minor damage; the terrorist were only mildly terrorizing. These barbarous acts drew the condemnation of many, including Hazel Brannon Smith, a small-town Mississippi newspaper editor.

The Civil Rights movement finally came to the beaches although it had been active in Jacksonville where it had been met by violence when Rutledge Pearson led demonstrations in August, 1960 against segregated lunch counters at the downtown Woolworth's, McCrorys, and Kress stores. One day, two African American youths accidentally knocked a white woman into a plate glass window. Then on another day two women got into a fight. On August 27th, hundreds of Klansmen and other bigots demonstrated in downtown Jacksonville with the police watching. When some young African Americans tried to get lunch counter service at the Grant's store and were refused, they were attacked by the white demonstrators who used ax handles and other weapons. They chased the teenagers into an African American section of town but were run out by an African Americangang. Police intervention stopped the riot. More "blacks" than "whites" were arrested, of course.

The city government of Haydon Burns, even though African-American votes put him in office, was racist. He was a powerful force in Jacksonville affairs as mayor from 1949-1965, when he became governor. Burns was a segregationist so he refused to create a biracial commission to resolve the issues. He was a determined conservative mayor of a conservative city. African-Americans threatened an economic boycott and white businessmen, fearing loss of profits, agreed to meet with African-American leaders and work out compromises. Desegregation began. "Green" was a more powerful color than white and "black."

Jacksonville had a large African American population, potential customers for the boardwalk; it had once been a majority African American city but annexations of suburbs changed that. In 1960, the city of 372,569 was 26.9% African American (100,169 persons); the Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area population was 455,411 was 23.2% African American (105,843 persons). However, the tradition of racial segregation meant that Beach business owner did not want the patronage of a quarter of the population of the county. This was not a Duval County phenomenon; racial bigotry was common throughout the United States.

Not many African Americans, either in absolute numbers or as a percentage of the total population lived on the beaches and the periodic influx of white tourists, civilian or military, shrank both numbers. The 1960 Census is instructive. Of the 12,049 persons living in Jacksonville Beach, 1,111 (9.2%) were African American; since Jacksonville provided most of the jobs at the beaches, it is not surprising. Atlantic Beach, a wealthier community of 3,125 persons, was home to 605 (19.4%) African Americans. The high percentage surely reflects the legacy of the fishing and U. S. Naval industries of Mayport, the Atlantic Beach Hotel, and the Florida East Coast Railway. Neptune Beach has three African Americans out of a population of 2,868., probably live-in servants.

The Census also had Division categories. The Jacksonville Beach Division of Duval County (covering more than the political boundaries) had 23,823 of whom 2,366 (9.9%) persons were African American. Palm Valley and Ponte Vedra Beach were small, unincorporated areas of the Northern St. Johns County Division, an area larger than these two tiny communities. This Division contained 5,020 persons of whom 391 (7.8%) were African Americans. Ponte Vedra Beach had been founded as an upper-income, private settlement and it was exclusive and wealthy.[7]

There were so few African Americans at the beaches and the adults were so well known meant that retaliation for any efforts to acquire access to the public beaches or to use the public accommodations of the boardwalk seemed highly likely. Councilman Moses Stormes, President of the newly-chartered Organization of American Rights, Inc., Franklin J. Left, Vice President , and Robert J. Taylor, Secretary Treasurer, were its officers; the Board of Directors included Chuck Franks, Chief of the Jacksonville Beach Police, A. W. Sands, Lieutenant of Police, Robert R. Craig, Sergeant of Police, Harry E. Burns, architect, James D. Smith, electrician, and Fred Downs, painter. The OAR sent a scurrilous letter in the Fall of 1960 saying that integration meant African Americans (the letter used a different word) would be raping white girls and other similar comments. It also issue a membership recruitment flyer (pictured). The members position on race and segregation was clear; it was to be maintained at all costs.

The OAR leaders went too far and most had to repudiate the letter and resign from the OAR. Left, Franks, Sands, Craig, and Downs resigned. Burns said he was never a member and condemned the letter. Taylor admitted that some of the language was objectionable and then resigned. Stormes, on the other hand, defended the letter. At a Council meeting in October, two different citizens rose to demand that Stormes resign. The Council members ignored them, perhaps indicating that they were segregationists.[8]

OAR Flyer Source: Austin Smith

The views of Stormes and his ilk did not reflect the views of others or, perhaps, others were practical. In my research in beaches newspapers, I found nothing about desegregation. My sense is that the local media cooperated to keep it from being an issue. The available accounts differ but the essential facts are the same.

Contemporaries described the events in an oral history session recorded at the Beaches Area Historical Society and Museum in Jacksonville Beach in early 2007. They noted that the integration drove whites away from the boardwalk but there was no violence. Because of the danger of retaliation, the 1,111 Jacksonville Beach African Americans tended not to pioneer. White tourists had come from north Florida towns as well as Georgia; the Chamber of Commerce had done everything it could to promote it. However, they expected a whites-only situation. With the beach and boardwalk being opened to all, many whites stayed away. Martin G. Williams, Jr. in a message to the author in June, 2009 believed that the boardwalk as he knew was dying in the 1960’s for several reasons. Many blamed integration in 1961 or 1962, a difficult situation that Mayor Justin Montgomery handled very well. Bus loads of African Americans were brought to the Beach and Boardwalk by the NAACP. White families stayed away. By 1970, the number of rides and amusements were sparse because business had declined. He noted “there was much competition from Daytona Beach, Myrtle Beach, Panama Beach, other vacation attractions and travel had gotten much easier. Disney and the Mouse arrived in Orlando, air conditioned hotels were common and golf and boating had become very popular. The family visitors from South Carolina, Georgia and Alabama were gone.”[9]

A quite different view emerges from an anonymous typed document possessed by the Beaches Area Historical Society, the view that civic leaders were progressive and quietly took the lead to achieve integration. This six-page document is unsigned and undated although may have been written in the late 1960s. It says the true story of what happened was revealed to a reporter of The Beaches Leader and that a member of the “black community” wanted it known. Some fifteen years before this essay was written, the City Council completed the Carver Recreation Center and swimming pool and began tackling the problem of substandard housing in 1955 in the African American section of town called “the Hill.” It took five years to complete the application process and begin construction but the City demonstrated that the government was not just for whites. They had integrated the city golf course, built 1963, without incident and it turned a huge profit in 1965.

In 1963, the mayor, W. S. Wilson, the City Council, and City Manager and other civic leaders such as Justin C. Montgomery, a former mayor and nephew a former mayor and city councilman, , decided that the time for change had come. They did not want the violence they had seen in Jacksonville or the demonstrations occurring in St Augustine in 1964 under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. They desegregated the beach or waterfront by quietly arranging for African American sailors, dressed in civilian clothes, to drive onto the strand on a busy Saturday afternoon and go into the surf. Law enforcement officers were hidden but acted quickly to disperse any hostile crowds. They would use the tactic of a fait accompli to desegregate further.

Before the Civil Rights Act of July 4, 1964 was passed Jacksonville Beach had desegregated its public accommodations. The Council asked the Chamber of Commerce to meet with local motel and restaurant owners and ask them to desegregate; ninety percent complied. On early June, 1969, the Chamber cooperated to desegregate the bars.[10]

Desegregation occurred in other important ways. African American citizens were not allowed at City Council meetings. Instead, the City Council came to them at the Carver Center. In Spring, 1965, at an outdoor ceremony for Beaches Welcome Day, invited groups were announced, applauded, and seat on the platform. Then came the group of African American invitees. They were announced, vigorously applauded and seated. The local high school, Duncan U. Fletcher, desegregate in 1967 without fuss.

Had not national policy and practice changed, whether Jacksonville Beach and its entertainment industry cannot be known. Certainly respect for the law and a more tolerant attitude in a resort community made a difference. Increasing dependence on the Navy at Mayport surely did. The armed forces had desegregated decades before. As the naval base at Mayport grew, its sailors had to have recreational place.

Jacksonville grew in part by annexations. In the 1920s, Panama Park, Ortega, Moncrief Park and the city of Murray Hill were absorbed. During the 1930s, the Ostrich farm property in 1931 and the city of South Jacksonville in 1932 were swallowed. The 1968 annexaton or consolidation made Jacksonville and Duval County synoymous but with a confusing aspect. Jacksonville Beach, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, and Baldwin (twenty miles west of the city center) were both separate municipalities with most of the attributes of any city but were also part of the City of Jacksonville. Their citizens voted in Jacksonville City elections, could hold public office, and paid taxes to Jacksonville. In short, it was a federal system.

The African American population percentage was diluted by consolidation in 1968 but has slowly increased since then. It is doubtful that the percentage will change much in the near future. In Jacksonville Beach in 2000, the US Census reported that 1,074 persons ( 5.1%) of the population was African American; 1,757 persons (13.1%) in Atlantic Beach; 66 persons (0.9%) in Neptune Beach; and 291 persons (1.5%) in the Palm Valley Census Demographic Profile which includes Ponte Vedra Beach. The beaches are becoming whiter.

CENSUS YEAR

Population

White

Percentage

Black

Percentage

1900

28,429

12,158

42.8

16,236

57.1

1910

57,699

28,329

49.1

29,293

50.8

1920

91,558

49,972

54.6

41,520

45.3

1930

129,540

81,322

62.8

48,196

37.2

1940

173,065

111,247

64.3

61,782

35.7

1950

204,517

131,988

64.5

72,450

35.4

1960

201,030

118,286

58.8

82,525

41.1

1970

528,865

401,695

77.1

118,158

22.3

1980

540,920

394,756

73.0

137,324

25.4

1990

635,230

456,529

71.9

160,283

25.0

2000

735,617

474,473

64.5

213,329

29.0

Will the African American population disappear? No. The ethnic composition of the Beaches will continue to change, however, as the ethnic composition of the United States and of Florida does. Hispanics are the largest ethnic group in the United States. One can reasonably expect more Hispanics to move to the Beaches.

Who were they? How did they earn a living? How different were their occupations from those of whites. To what extent was there “class distinctions” within the various African American communities? Did people who worked for the Ponte Vedra Inn or the Atlantic Beach Hotel, both prestigious institutions, consider themselves different?

What sources exist? Are there letters, diaries, and similar documents in private hands that could shed light on African American history at the Beaches? Surely, official records, including school records, would provide information. City directories can help even when “race” was not identified; they have a wealth of detail but are seldom used. Photographs tell a story but a picture is not worth a thousand words in this case. There is much useful material in this essay that an enterprising student can use. My contention is that Beaches history cannot be understood fully unless one knows the history of African Americans of the Beaches. Surely there are graduate students at the University of North Florida or some other university who could write one or more theses.

Possible Sources

“Mr. Roosevelt Insists on Talking to Negroes, Demands a Change in Plans of Jacksonville Committee,” New York Times, October 16, 1905.

“The Color Line in Florida, Negroes Not Allowed to Ride with Whites in Jacksonville Cars,” New York Times, November 7, 1901.

Andino, Alliniece T., “40 years ago this weekend, Jacksonville gave itself a national

reputation for violence,” Jacksonville.com, August 25, 2000

Bartley, Abel A., “The 1960 and 1964 Jacksonville Riots: How Struggle Led to Progress,” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 78, No. 1 (Summer, 1999), pp. 46-73.

________, Keeping the Faith: Race, Politics, and Social Development in Jacksonville. Westport: Greenwood, 2000.

Beaches Area Historical Society. http://www.beachesareahistoricalsociety.com.

Bull, Harcourt. Papers. Hel by the Bull Family, Atlantic Beach, Florida.

Crooks, James B., Jacksonville After The Fire, 1901-1919: A New South City. Jacksonville: University of North Florida, 1991, p. 13.

Crooks, James B. Jacksonville: The Consolidation Story, from Civil Rights to the Jaguars. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.

Duval County Schools, Negro Schools of Duval County, 1955-56. http://bit.ly/aXrJ5V.

Feagins, Karen, “Jacksonville Beach: Against The Tides,” WJCT-TV, February, 2010.

Fitzroy, Maggie, “Tea party triggers fond memories of The Hill at Rhoda L. Martin Cultural Heritage Center,” Shorelines, Jacksonville.com February 27, 2010.

Florida, Department. of Agriculture, The fifth census of the state of Florida taken in the year 1925: in accordance with the provisions of Chapter 6826, Laws of Florida, Acts of the Legislature of 1915. (Tallahassee: T. J. Appleyard, Inc., 1926, p. 20. Found at http://bit.ly/9ngDNe.

Florida State Census, 1935. Department of Agriculture, Florida Seven Census, 1945.

Florida Memory Project. http://www.floridamemory.com/

Florida Heritage Collection. http://palmm.fcla.edu/fh/

Florida, State Library & Archives. http://dlis.dos.state.fl.us/library/flcollection/index.cfm

Florida Digital Newspaper Library. http://www.uflib.ufl.edu/digital/collections/fdnl/

Hagan, Diane, ““Beginnings of the Black Community in Jacksonville Beach,” Student paper, University of North Florida, 1975. Copy in Beaches Museum and History Center,, Florida Jacksonville Beach .

Jacksonville, Florida, Council of Social Agencies, Jacksonville Looks at Its Negro Community. 1946. http://bit.ly/9uPQQa

Jacksonville Journal, June 12, 1969.

Jacoby, Jeff, “The enemies of Jim Crow, “ Boston.com, February 15, 2009.

Levine, Shira, “"To Maintain Our Self-Respect": The Jacksonville Challenge to Segregated Street Cars and the Meaning of Equality, 1900-1906,” Michigan Journal of History, Winter, 2005.

Mabry, Donald J. World’s Finest Beach: A Brief History of the Jacksonville Beaches. Charleston and London: The History Press, 2010.

_______, Neptune Beach Before 1931 , Historical Text Archive, 2006.

_______, A Man and Three Hotels, Historical Text Archive, (2006).

________, Harcourt Bull's Atlantic Beach, Historical Text Archive, (2007).

________, Beaches Veterans in WWI, Historical Text Archive, (2007).

________, Florida's Napoleon, Historical Text Archive, (2008).

________, Carnival on the Boardwalk, Historical Text Archive, (July, 2009).

________, Baseball on the Beach, Sea Birds, 1952-54 , Historical Text Archive, (2008).

________, Mighty Mayport Florida Beats Jacksonville, Historical Text Archive, (2009).

________, Yankee Engineer in Florida , Historical Text Archive, (October, 2010).

Organization for American Rights, Inc. “This is For You!” handbill.

Pablo Beach, City of. Charter and Ordinances of the City of Pablo Beach, 1924.

Pate, Jack, “A Trip To The Beach.” Tidings From the First Coast. Beaches Area Historical Society, says the actual amount of 12,067 acres of “Swamp and Overflowed Lands”, which the state deeded to the J.& A. on 19 February, 1886 “in consideration of the completion of the railroad from Jacksonville to Pablo Beach”. (Archibald Abstract Books, Ofc. No. 26109). Phelts, Marsha Dean, An American Beach for African Americans. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1997.

Piscitelli, Steve. “Donner Subdivision: The Rhythms of a Community,” Neighborhoods, Florida Times-Union, January/February, 2000, pp.33-35.

Rhoda L. Martin Cultural Center. http://rhodalmartin.org/default.aspx.

Richard's Jacksonville Duplex City Directory. Jacksonville: John R. Richards & Co., 1887.