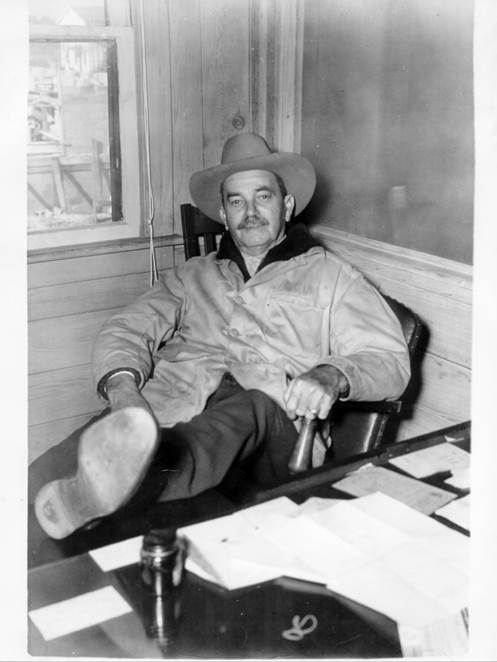

This is a story of a remarkable man, born in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and died in the second half of the twentieth century, who built and built and left a fine legacy to his children. It’s a story of personal determination and ambition, of grit, of mules, of moving tons of sand, of developing ocean side communities, of machines, and of housing people. It’s a story of generosity when none was demanded. It’s the story of a man named McCormick who lived, thrived, and died in northeast Florida when the area was still close to the frontier stage except for the city of Jacksonville.

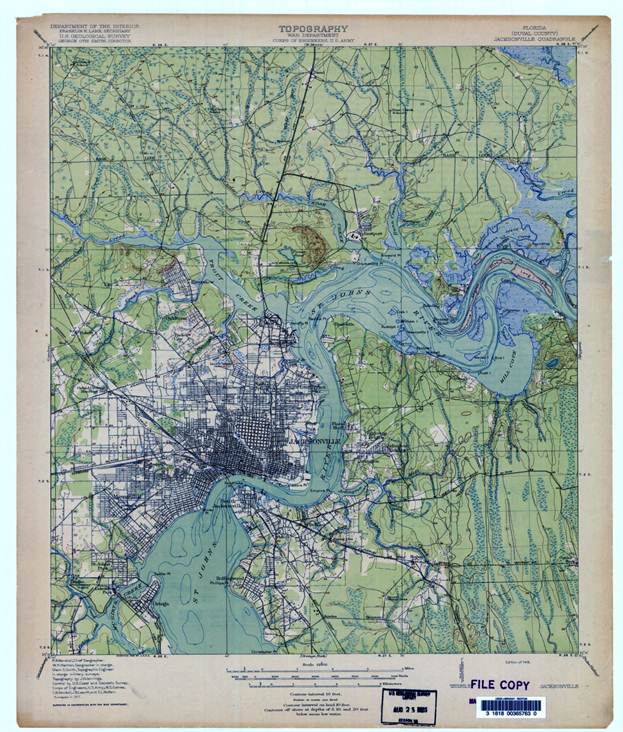

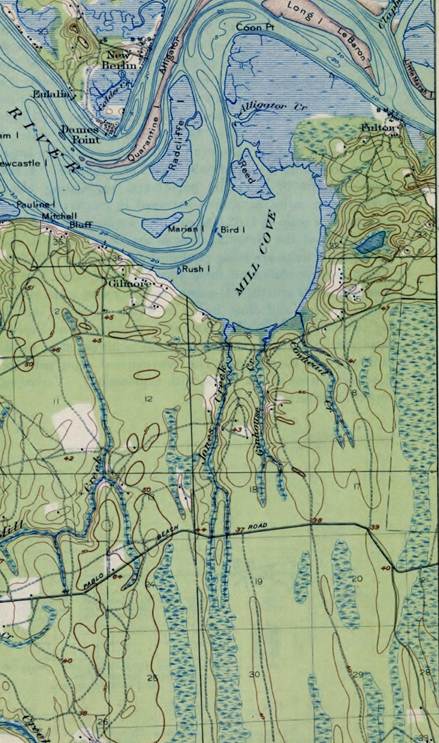

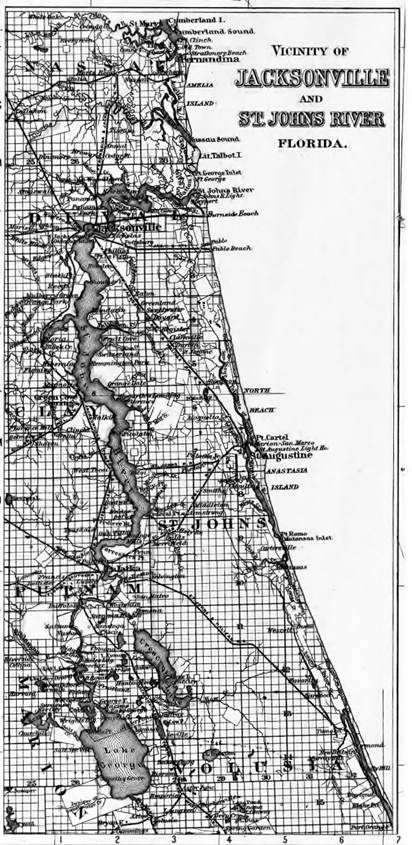

His birth place was close to the languid St. Johns River which flows slowly 310 miles north from central Florida to Jacksonville and then bends east to the Atlantic Ocean. It’s almost like a long, skinny lake that widens to three miles in places. Even its mouth has to be dredged and channeled by long jetties to make for safe navigation. In 1877 and for many years thereafter, few people lived along the lower reaches of the river. A few miles upriver lay the bustling Jacksonville, Florida’s largest city, contained only 7,650 people. Duval County, an area of 918 square miles, was home to 19,431 persons. The McCormicks had migrated there from South Carolina before the Civil War, seeking cheap land to farm. Why they settled in the Mill Cove-Fulton area is not known; since land transportation was arduous in the overgrown countryside, even on sandy trails and roads, the river had to be the primary factor.

Benjamin Bachelor[1] McCormick was born on April 13, 1877 in the Mill Cove region near Fulton on the St. Johns River. It was frontier land east of Jacksonville, forested wilderness with cleared sites connected by dirt and sand roads and the river to Jacksonville. His grandparents, John Benjamin McCormick and his wife Marinda (née Elliott) of South Carolina, settled there after the Civil War because land was relatively cheap. They could sell their excess farm produce to city folks while supplementing the family diet with fresh fish and game. Their son and daughter-in-law, Stephen Wright McCormick and Martha Ann Elizabeth (née Raley), had seven children of whom Ben was the second oldest. Ben spent his childhood mostly doing chores, hunting, and fishing. Rural Fulton offered little in the way of formal education; the only public schools in the county were in Jacksonville and not many at that. What he learned came from family and church. He was a smart boy who paid attention to life around him and learned. He was a hard worker although he suffered ill health as a child. Boyhood friends remember him as generous and willing to fight against injustice.[2]

During his childhood, he visited what would eventually be called “the beaches” riding in a wagon all day to get to the home of a family friend, “Uncle” Tillman Grace, a member of one of first four resident families. Grace lived in what is now north Ponte Vedra Beach. B. B. McCormick never forgot the trip, speaking of it to the Ocean Beach Reporter, remembering the year that he and his older brother, Townsend (Townie) visited as 1882.[3] The visit was a portent.

The McCormick move to northeast Florida was a shrewd one for Jacksonville and the Duval County had begun to boom and would continue to do so for over a century. Jacksonville was the railhead for Florida; railroad companies expanded the web of tracks throughout the state for years. Ocean going ships docked there as well as river boats. Work could be had for those who wanted it. Tourists came to enjoy the warmer winters in city hotels or to sail on the tourist steamboats going upriver to Lake George and Sanford in central Florida. The late 19th century was the railroad age for the state with Jacksonville as the entry point. Ships plied the river, especially after the city government financed docks and the federal government dredged a channel and built jetties at the river's mouth. Timber and naval stores were the primary exports although commercial citrus fruit agriculture was important until freezes forced it southward. Great fortunes were earned through the timber industry. Of course, people supplied markets with fish, fruits, vegetables, and livestock. For some, employment was creating infrastructure—roads, railroads, bridges, culverts, lumber mills, docks, and ships.

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

|

Jacksonville |

7,650 |

17,201 |

28,429 |

57,699 |

91,558 |

129,549 |

173,065 |

204,275 |

Duval County |

19,431 |

26,800 |

39,733 |

75,163 |

113,540 |

155,503 |

210,143 |

304,029 |

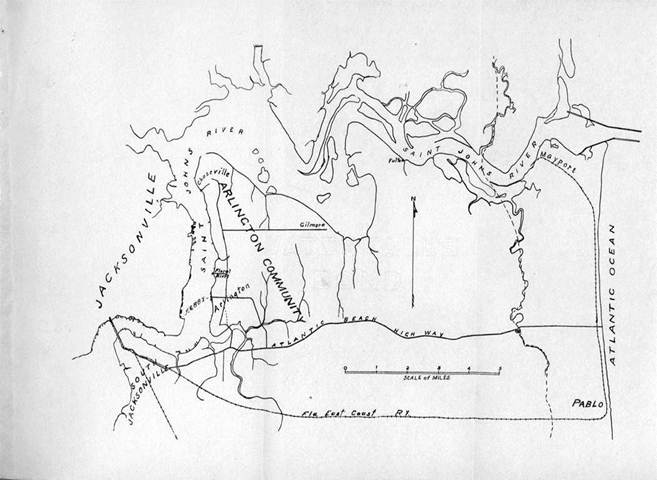

B. B. McCormick spent his working life involved in the growth

of northeast Florida, mostly on the Atlantic Coast beaches east

of Jacksonville. His older brother, John Townsend McCormick (born

in 1875) was a railroad conductor. Perhaps he influenced the

appointment of his 17-year-old brother Ben to the position of U.

S. Postal Service mail carrier from Fulton to Cosmo and back.

Cosmo, south of Fulton, was a station on the Jacksonville,

Mayport and Pablo Railroad which had been built between Arlington

and Burnside Beach on the Atlantic east of Mayport. “The

JM&P had a twice a day schedule with stations at Eggleston,

Gilmore and Cosmo, and stops at other remote settlements along

the way.” Ben earned $15 a month ($180 a year), not bad

when the average working man in the U. S. earned between $400 and

$500 a year and the average annual unskilled worker in the South

earned $300 a year.[4] The job familiarized him with the terrain and

its settlements.

He increased his income in 1899 by tackling the grueling job working on the crew that surveyed and built the right of way for the extension of the Florida East Coast Railway from Pablo Beach (now Jacksonville Beach) north to Mayport on the river. He was paid $1.25 a day. Henry M. Flagler had bought the little tourist railroad that ran from South Jacksonville to Pablo Beach, replaced its rails with standard gauge rails and continued to Mayport where he built coal docks. He needed coal for the trains in the FEC system which he was building southward to Miami and, eventually, Key West. Later, B.B. and a crew of 30 African Americans used wheelbarrows and shovels to help build the road from Pablo Beach to Mayport paralleling the FEC Railway.[5]

Florida lumber production reached 1.25 billion board feet by 1909; McCormick worked in sawmills and, in time, became a millwright, building mills in the northeast part of the state until 1916. Timber and naval stores were very important in the Northeast Florida economy with the port of Jacksonville on the St. Johns River being the shipping point either upstream to central Florida or downstream to the Atlantic Ocean. He maintained an office in Jacksonville but spent much of his time on the road building mills.

On June 1, 1904, B. B. McCormick married twenty-one-year-old

Dorothea Elizabeth Oesterreicher[6], the oldest of nine children.

According to family lore, he had first met her when the wagons of

Thomas Oesterreicher and Stephen McCormick met on the Kings Road

which connected Jacksonville and St. Augustine. Naturally, they

stopped and visited, giving the young people a chance to assess

each other. Dora, as she was known, was beautiful and caught his

eye; he fell in love. Family lore says that he would walk for

hours from what is now Fort Caroline Road to 20 Mile Road,

ostensibly to visit her father Tom but really to see her. The

Oesterreichers must have understood what was happening and been

impressed with this young man who would travel so many miles

to see their daughter. Neither family had much money—both

were hardworking, ordinary families, pioneers in the back

country. McCormick had determination and was not afraid of work,

fine attributes in a son-in-law. They gave their permission and

B.B. married Dora on June 1, 1904 at her parents’ home in

Palm Valley.[7]

Ben was marrying into an industrious extended family. The

Oesterreichers were Germans from Austria, but her mother, Ella

Ortagus, was a Minorcan, Spaniards who had entered Florida in the

late 18th century. Cousins in Palm Valley and down in

St. Augustine were Minorcan for the most part.[8] Like McCormick,

Palm Valley people worked hard.

The new family went where Ben could find work building saw

mills, necessitating constant changes of abode. On August 22,

1905, Dora bore the first of eight children, Edwin Wright

McCormick, in Oak Hill, Florida in southern Volusia County. The

next year on July 4, 1906, Edith was born only to die the next

year. Benjamin Richard McCormick was born on Tyler Creek in Levy

County south of Gainesville on December 11, 1907. He would be a

major force in B. B. McCormick & Sons later in life. Ella

Dorothea McCormick came into the world on July 06, 1909. Julian

M. McCormick was born on January 14, 1911 in Morgan Mill,

Florida, south towards Sanford.

After so much moving, the family moved to Jacksonville in 1911

and he began building a house at 1108 East 13th Street

at the corner with Phoenix Avenue in the Brentwood neighborhood.

The property was three miles from Hemming Park, the center of the

city’s business district. They were able to garden and sell

produce to supplement the family income. B. B., according to the

1914 Polk City Directory, was an engineer. His first biographer,

Frank E. Doggett, says his major occupation until 1916 was as a

millwright. Sometime before U. S. entry into WWI in April, 1917,

he worked in a shipyard which built wooden ships. By 1919, he was

listed as a carpenter. Either occupation is consistent with

working with sawmills.[9] The home on East 13th street was

where his last three children by Dora were born. Martha Nita

McCormick arrived on October 9, 1913; John Townsend McCormick on

October 5, 1915; and Gertrude Edwarda McCormick on November 26,

1918.

With a wife and seven children, he needed to find more income so

he went into the timber logging business in 1918, purchasing a

tract of timber land just west of Pablo Beach. The next year, he

borrowed a thousand dollars from a Jacksonville businessman and

bought a logging cart, two mules (Buck and Skinny), and pine

timber on a hammock at the beach. He cut timber, hauled it to San

Pablo Creek, and floated it by raft to Jacksonville.[10] It

was hard work in the sometimes blazing sun and he always wore a

hat, which became his trademark.

Finances were doing well enough in 1919 that he was able to rent rooms in a rooming house, The Owl, in southern Pablo Beach [approximately 12th Avenue South] for a month. His children were sickly and he believed that taking them to the beach with its salt air would help. So he, his wife, and seven children packed a wagon with supplies for the month in preparation for a next day departure. It was a long trip to the south side of Jacksonville and then east on narrow Atlantic Boulevard to the beach.

Opportunity knocked in the form of what seemed at the time to be a tragedy. Their home burned to the ground with all their money and possessions, other than those in the wagon. No one was hurt, however. B. B. decided to go the rooming house, The Owl, as he had planned. They would be closer to his in-laws, the Oesterreichers. His uncle, R. D. McCormick, drove the wagon to the foot of Atlantic Boulevard. There was no road south to Pablo Beach so they walked 3.5 miles on the beach at night, carrying their meager possessions, the older children carrying the younger ones . They went to The Owl where Dora cooked in the yard. The head of Furchgott’s Department Store, Fredrick Mayerheim, had kindly helped them acquire clothes and other supplies.

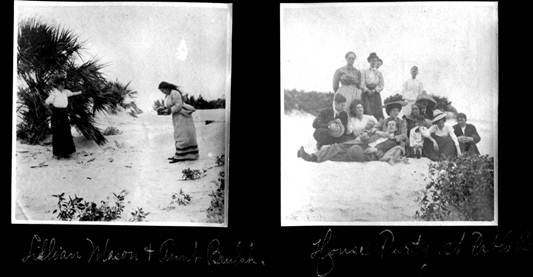

B. B. had begun working in the area in 1918 but was oriented

to Jacksonville; now he would focus more on the beach area. He

was where he could do the most good. It needed someone with his

drive and talent. Greater Pablo Beach had only 442 persons of

whom 357 lived in the village itself. Atlantic Beach had less

than 100 people clustered around the Atlantic Beach Hotel.

Further north was Mayport with 399 people living adjacent to the

St. Johns River. Mineral City [Ponte Vedra Beach] had declined

with the end of WWI. Palm Valley had few families scattered in

farms. Whereas Jacksonville with its 91,558 people had plenty of

men with technical skills, B. B. was a rarity at the beach. The

coast was mostly sand dunes, underbrush, small creeks, standing

water or ponds, and a few trees. The settled areas were expanding

with the growth of tourism and beach retreats necessitating the

work that McCormick could do. One can see the sand dunes in the

heart of Pablo Beach in these photographs of Lillian Mason & Aunt

Beulah and of their house Party at Pablo Beach taken about

1919-1922.

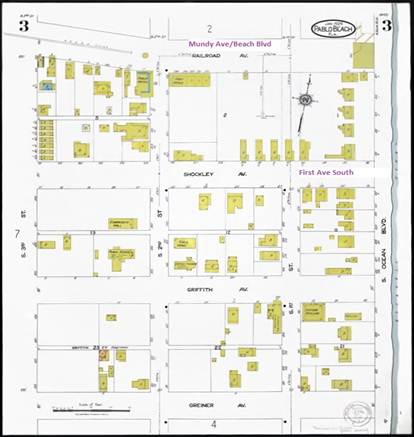

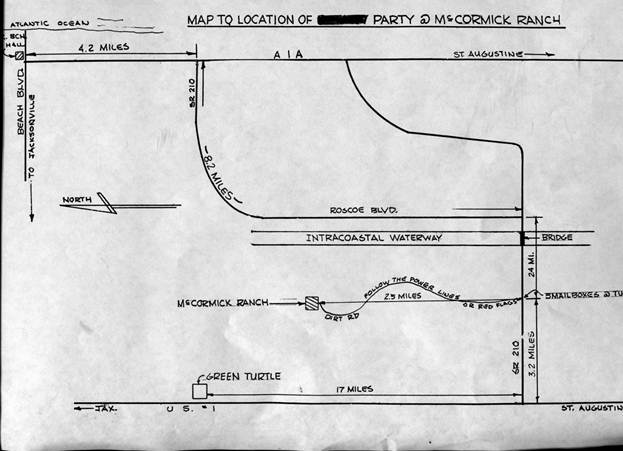

Figure 8 Duval County, 1932 US Department of the Interior

Geological Survey, 1932

He added a contracting business to his timber business and demand became so great that contracting became foremost. He established his base of operations in the African American section where most of his employees lived.[11] With them and mules, he cleared, mucked, dredged, filled, poured concrete, crested shell drives, landscaped, and even moved houses. He bartered building roads or pouring concrete or other heavy construction for land in addition to working for money. For example, the Pablo Beach News (April 15, 1922) reported that he filled in the Foss property according to the Board of Public Works and, on June 10, 1922 began grubbing, grading, and leveling of Suwanee Avenue (10th Avenue South) to the Buck & Buck Oceanside Park addition.[12]

He also began building a home for his family, a home at 225 First Avenue South where he would live until his death. As the Mayport News (September 16, 1922) reported he was erecting a “fine, two-story house” on his property on Shockley Avenue near Second Street. First, he had to fill in a railroad rail bed from a spur which had run to Mineral City. Then he filled in a huge mud pond filled with alligators. Unable to shoo one away, he filled the pond to a depth of 6-8 feet. Then he laid the foundations sixteen feet into the ground. In all, 4,402 wagon loads of earth were moved. The large house would have every modern convenience. He would borrow furniture to move his family into the new house.[13]

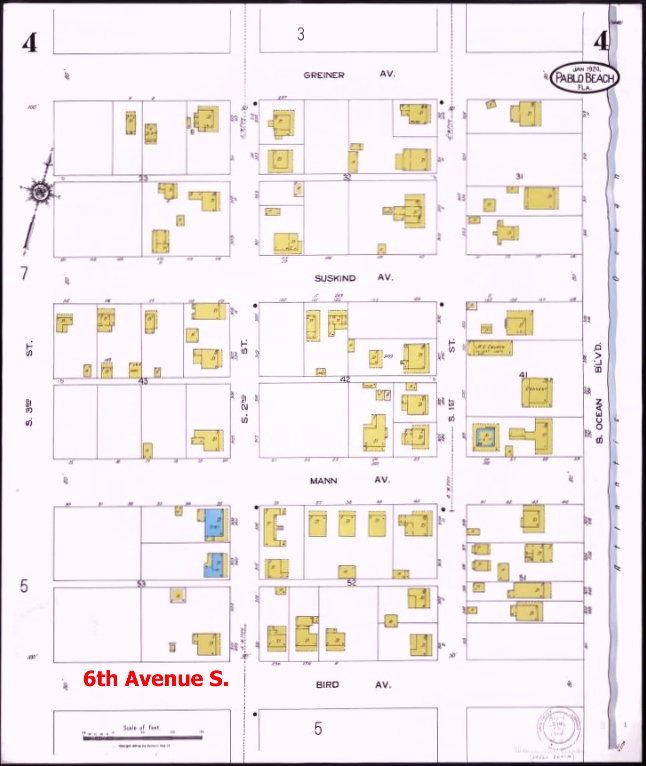

This and the other Sanborn Fire Insurance maps used show the existing buildings for the year they were created. Pablo Beach changed street names in 1937 so I have marked the current name on the map. What is important is to see how few buildings there were. Although the maps don’t show it, the existing roads were often not paved. The roads also might be platted but not exist. McCormick chose to live in the center of town near a school for his children.

He had come to stay. In 1920, he gained permission from the Duval County School Board to correct the Pablo school drainage by filling and grading the school grounds for free. Sand dunes by the ton were moved to fill a pond on the grounds. A few years later, on March 7, 1923, he petitioned the Duval County School Board to establish a special tax district for the beaches. The election on May 1 was successful. Next, on June 2, 1923, a successful petition to issue bonds, acquire property, and build a school was made. Monies became available to build a new school. McCormick was elected to a two-year term on the board of the tax district and was reelected and reelected. He devoted himself to improving education on the Beaches not just because he had children in public school until 1947 but because he believed society needed an educated citizenry. [14]

Dora died on October 20, 1922, shortly after he had begun construction of the family home. They had been through much together in eighteen years, living in a variety of places before finally settling in Pablo Beach not too far from her ancestral home in Palm Valley. Their children provided some company and even help with each other. Ed,17 was the oldest; Ben 15; Ella, the oldest daughter, 13; Julian 11, Martha 9, John Townsend II (J. T.) 7, and Gertrude almost 4. He had to have help with his household and must have turned to a servant as well as to Dora’s family and to his own. He worked very hard, long hours in a physically demanding occupation to support his family and himself as well as being an active civic leader.

In 1925, he joined a group which presented a survey to the Duval County Board of County Commissioners for a proposed second highway to the beaches from Hogan Road. This highway would have entered the beach at what is now 37th Avenue South almost at the county line, close to where J. Turner Boulevard now enters the city. Obviously, the Jacksonville Beach (the town renamed itself in 1925) people were fostering the growth of their town. The county was reconstructing Atlantic Boulevard and had no interest. Had it been built as surveyed, the history of the beaches would have been dramatically altered. That McCormick was part of the group demonstrates his standing in the community.

Early in 1926, not much before he remarried, he purchased the 40 acre homestead of Captain Robert Mickler which included a Southern “Colonial Style” home. McCormick stocked the property with cows, chickens, and other livestock with plans to retire there eventually. He was only 49 years old, however, and in the prime of his life.[15] His property in the Palm Valley-20 Mile area would be both a source of sustenance and a retreat for his family. Dora’s people were nearby.

Staying busy with work and civic concerns was not enough for man like B. B. He needed a wife and a mother for his children and there were few eligible women available. According to the Florida State Census of 1925, only 544 white people lived in Jacksonville Beach, 430 in Mayport, and 117 in Palm Valley. Five years later, Atlantic Beach had only 164 people total, many of whom were African American. So it is not surprising that he and his sister-in-law, Maude Oesterreicher, got married on February 25, 1926. Maude, born March 23, 1904, was the youngest of the nine Oesterreicher children. Maude and Ben were a handsome couple who had two children, Clarence and Miriam.

In 1928, he won the $125,000 contract to build a road, the future A1A, from the northern St Johns County line south to Vilano Beach (almost to St Augustine), a distance of about twenty-four miles. He did not use surveyors but built it line-of-sight by staying just west of the sand dunes on the ocean front. The work was a massive undertaking with numerous workers and a herd of mules using shovels and slip pans to remove vegetation and sand and grade the road (The photo below shows such a work crew). Wells were dug at strategic points on the route for the crew and the mules. His sons worked on the project as well. Even J. T., his son, did some of the cooking. With this crew the highway was complete in little more than ten months starting on November 5, 1928 and ending September 15, 1929. The state had not appropriated the funds to extend the road into Jacksonville Beach so he did at his own expense.[16]

As McCormick expanded his construction business, he relied

more and more upon African Americans for his labor force. As

Diane Hagan notes:

During the early history of the beaches, the McCormick Construction Company employed more Blacks than any other area business. The company built A1A from Jacksonville Beach to St. Augustine and employed many black workers. The workers earned $1 per day, which was not unusually low in the teens, 1920’s and 1930’s. The McCormicks maintained separate quarters and a commissary for the black employees.[17]

Testimony to such generosity came in a letter he received from W. P. Coyle:

First I shall never forget the first deep impression that I had of you, late one saturday [sic] evening during the Hoover depression when men, women and children were walking the streets of our land begging for food, medical aid and shelter. I was talking to you in front of your house when an old negro [sic] came up and said to you; Scuse [sic] me Boss but will you lend me two dollars and fifty cents for bus fare to go to New Smyrna to see my sick wife who is calling for me? After thinking a while you looked up at him and said: John I have only one thin dime to my name but I have an automobile and credit for gasoline so get ready to go see your sick wife.

At his death in 1953, preachers of the three African American churches fondly remembered him not only for the jobs he provided but also for his many kindnesses.[18]

By 1927, he was expanding his business to include building houses. He bought a “choice lot” at the corner of First Street South and Bird Avenue (6th Avenue South ) with plans to build modern bungalows.[19] He would return again and again to building houses and apartments as population growth created demand.

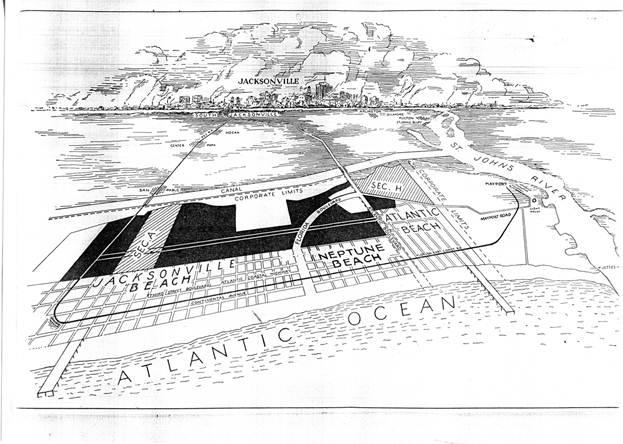

Always trying to foster the growth of the beaches, Jacksonville Beach in particular, he and some others made a survey for a possible highway route which branched from Atlantic Boulevard and parallel the Florida East Coast Railway line to the beach but coming into Jacksonville Beach at Twelfth Avenue South. Nothing came of this December, 1929 effort but the constant pressure would eventually bring success.

The beach communities would experience a growth spurt in the 1930s. Whereas Jacksonville Beach had grown to 409 in the city limits and to 882 in total by 1930, it had grown to 3,566 in 1940. Atlantic Beach had 164 in 1930 and 468 a decade later. The Mayport precinct had grown to 1003, with 511 living in the village itself but 1,290 in 1940. Neptune Beach, split from Jacksonville Beach in 1931, contained 1,363 people in 1940. Ponte Vedra (as Mineral City had been renamed) was included in the Palm Valley U.S. Census count; the Palm Valley precinct had 68 people in 1930 and 341 in 1940, reflecting the development of Ponte Vedra.

The beach communities were affected by the Great Depression which began in 1929 but not as severely as the nation. By the summer of 1933, the unemployment rate was 25% and higher in the major industrial and mining centers whereas farm income had fallen by over 50%. Farmers were losing their farms to mortgage foreclosure while 844,000 nonfarm mortgages had also been foreclosed between 1930 and 1933. The existence of a tourist industry, focused on the carnival-like boardwalk in Jacksonville Beach helped. Just as movie attendance increased in hard economic times, people went to the beach for relief. Some stayed. The New Deal spent millions at the beaches and that attracted people in search of jobs. One job supported several people. When the wooden boardwalk burned in 1933, federal money paid for much on its once concrete replacement.[20] His construction firm “began the bulkhead and seawall along the oceanfront.” Duncan U. Fletcher Junior-Senior High School was erected and opened in 1937; McCormick prepared the site. McCormick, in an interview with Virginia Taylor, said “that he had taken part in building every street and road in the eastern part of Duval County with the exception of the highways built by the Works Progress Administration.”[21] General contractors such as the McCormick firm owed their success to government spending on infrastructure. His company also did quite a bit of private work including the physical development of Ponte Vedra Beach and the Ponte Vedra Inn & Club and its golf course beginning in the mid-1930s.[22]

His dream of a new highway to the beach came closer to being fulfilled. In 1937, the County Commissioners paid the Florida East Coast Railway Company $8,500 for the right-of-way from Atlantic Boulevard at St. Nicholas to Third Street in Jacksonville Beach. The state legislature designated this as State Road No. 376. The County Commissioners sponsored a WPA construction project for $1,576,00 of which the United States government would pay $500,000. Work began to clear the right-of-way, install drain pipes, excavations, and grading the roadbed. Construction stopped in the Fall of 1941 and would not resume until the end of the war in 1945. [23]

During the Great Depression, McCormick acquired land, some of it underwater, from Jacksonville Beach in 1937 and filled it in to make it high and dry. The city had little cash for jobs it needed for him to do so it traded land for his firm’s services. He would eventually build on this land. His major housing project in the Great Depression came in 1938 when he tore down Dixie House and built the Pioneer Apartments on Mundy Drive [eventually Beach Boulevard] close to his house in one direction and one block from City Hall. His wife, Maude, managed the twelve apartments, corresponding with prospective occupants and collecting rent for either short-term or long term lets. For example, a Mrs. Leonard A. LeFiles of Valdosta, Georgia rented an apartment for herself and her husband, preferably on the first floor, for the week beginning August 12, 1941. A sheet from the Pioneer Apartments ledger book for 1940 shows one tenant paying $50 each month for rent and utilities.[24]

By 1945, when he was 68 years of age, he had lived a fuller life than most men. He had lost his Julian in a car accident in Brunswick, Georgia on February 28, 1936. His mother died February 19, 1937. His youngest son, Clarence, served in the US Navy. Edward, the oldest, had been Jacksonville Beach police chief for eight years and constable for two years before turning to work for the family corporation. Ben (Benjamin R.) was general manager. J. T. received an engineering degree from Tri-State College[25] in Angola, Indiana, the first of his family to finish college, and joined the firm. His three oldest daughters were married. Miriam was a Fletcher High School student. He had begun serving as Jury Commissioner in 1938, a job he would continue until 1946 and he was a school board trustee, which would continue until 1947. His 1,700 acre farm was feeding his family with produce, livestock, wild game and sugar (from sugar cane grown there).

Then World War II came and changed everything. B. B. McCormick and Sons, Inc. soon had a tremendous amount of work. The three oldest sons had been modernizing the business with machines and better construction techniques. Gone were B. B.’s beloved mules. In 1941 through 1945, the company constructed barracks and airfields in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Brazil. It worked on the nearby Navy Base in Mayport. It constructed twenty-two airfields during WWII. According to The Beaches Outlook, he was spending $50,000 a year for repair parts for his motorized fleet in US and abroad in 1942-43. At home, in May, 1943, he began building 15 two-story masonry duplexes using Federal Housing Authority mortgages to finance construction. Manuel Chao supervised the construction. This project was finished by late 1943 and was managed by McCormick Realty Investments, Inc. The buildings were built in clusters of four east of Third Street—214, 215, 220, 211 on 7th Avenue North and 214, 215, 220, 283-285on 8th Avenue North in Jacksonville Beach and 224 Myra, 220, 221, 226 on Pine Street, and 212 on Oak Street in Neptune Beach.[26]

His body was failing but not his mind but he thought it best, in 1944, to turn his million dollar corporation over to his sons. He continued to play a role in the corporation, seeing it achieving some of his goals for the beaches such as the construction of a huge housing complex and the completion of Beach Boulevard. He had time to reflect publicly on key workers and friends. He had a deep appreciation for the men who worked with him for 20 or more years—George Refoe (his first teamster, hired in 1913), George McDuffy, Julius “Black Man” Johnson, Odell Jackson, and Cecil Jackson and for his friendships with James Gonzales (city electrician), George Zapf, George E. Trimble, Martin G. Williams, and J. B. Arnot and the late Edgar Compton.[27]

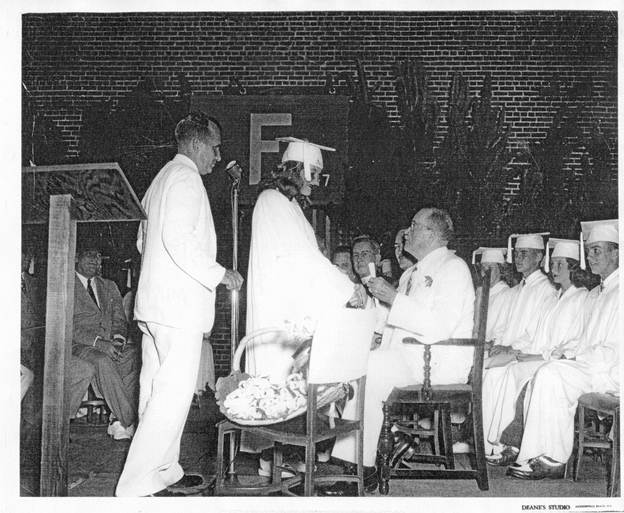

On May 26, 1945, he awarded the diplomas at the Commencement of Duncan U. Fletcher High School. Then, in June, 1947, he again awarded diplomas, including to his daughter Miriam. He was also honored by being named an honorary graduate of Fletcher. He then vacated his school trustee position because of ill health. The “Father of the Beaches School System” had done his job.

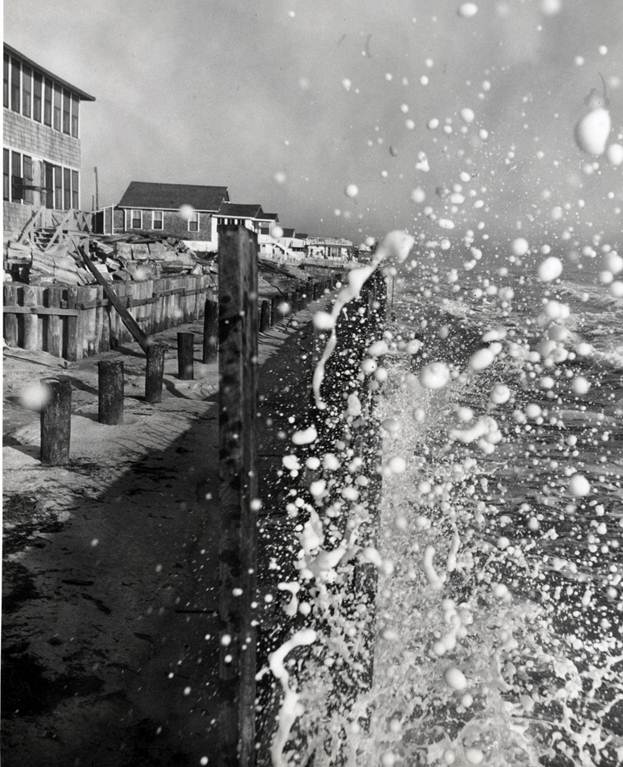

His construction firm returned to domestic work after the war. One mainstay was constructing or repairing bulkheads. In 1947, a very strong northeast storm, a Northeaster, destroyed parts of the bulkhead, washing the sand shore to the sea. Naturally, the McCormicks were hired to fix the damage. The photograph above shows such work. More work came in 1948. The firm was contracted to repair the seawall at the street end of Third Avenue South at a cost of $3,934. The wall would be 62.6 feet in length. Simultaneously, the city required that the adjacent property owners to the south would also have to build sea walls.[28] And there was roadwork.

Once the war ended in August, 1945, construction of the new

beach highway, McCormick’s dream since 1922, began in

earnest. It was originally designated State 376 but renumbered as

State 212. On October 19, 1945, Atlantic Dredging and

Construction Company began a $219,234.99 project to construct a

hydraulic embankment for approaches to the bridge over Pablo

Creek. B. B. McCormick & Sons began construction on the 1.349

miles from Third Street west to the approach of the bridge with

$335,189.56. This segment was begun on October 10, 1946 and

completed September 20, 1947. The firm received another contract

of $136,158.51 to pave 1.28 miles toward the bridge with service

roads. This last segment was begun November 1, 1949. To cross

Pablo Creek (now Pablo River) the state hired George D. Auchter

Company to construct twin bascule bridges, the B. B. McCormick

Bridge. The total cost of the highway was $3,546,000.

On December 17, 1949, B. B. McCormick arrived by ambulance to

cut the ribbon on the B. B. McCormick Bridge. From his gurney, he

used his pocket knife to cut the ribbon opening the bridge; Ed,

J.T., and Ben helped. He was down but not out.[29] It was a great

legacy.

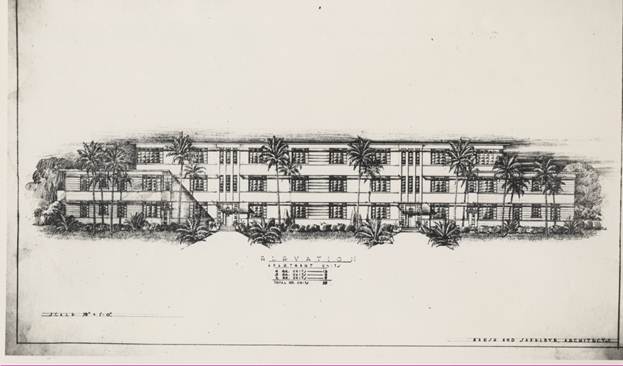

McCormick had become involved in real estate development in the 1920s; he and his sons began building with a vengeance in the 1940s to meet the demand created by people flocking to the beaches. In 1947 and 1948, McCormick & Sons constructed the Beaches Homesites Subdivision (5th to 10th Streets North between 9th and 13th Avenues North. H. A. Durden surveyed and divided the land into about 200 lots. The firm sold a few lots immediately to individuals but then sold the rest to the Ernest F. Shad Investment Company in 1951. The company’s efforts focused on building a massive apartment complex “with $44 million in government-backed mortgages via Liberty National Life Insurance Company and Stockton, Whatley, Davin & Company. The project met requirements of FHA’s section 608 veteran’s emergency rental program. In total. All of the apartments were between 1st and 3rd Streets both south and north of Beach Boulevard, some of it on the old Florida East Coast Railway right-of-way that ran from Jacksonville Beach to Mayport. Other parcels were land B. B. had acquired through the years.[30]

The plan was to build 354 dwelling units for Jacksonville

Beach between 1st and 3rd Streets:

38 dwellings between South 15th and 16th

Avenues

2 buildings between South 2 and South 3rd Avenues

having 28 dwelling units

6 buildings having 88 units between North 15th and

16th Avenues

2 having 16 units between North 6th and 7th

Avenues

4 buildings having 32 units between North 7th and

8th Avenues

4 buildings having 32 units between North 8th and

9th Avenues

2 buildings having 56 units between North 9th and

10th Avenues

2 buildings having 56 units between North 10th and

11th Avenues

1 building with 8 units between 13th and

14th Avenues

1 building with 8 units between North 14th and

15th Avenues

B. B. conceived the project but his older three sons were

carrying out his plan; Ben was President, Ed the Vice President,

and J.T. the secretary-treasurer of the corporation.

The first set, 30 units on 2nd Avenue across from the elementary school, were opened for inspection on August 14-15, 1948. They were one and two bedroom furnished apartments. Thousands came to see them and some to rent. About 80% of the renters were from out of town. McCormick and sons sped up the construction of other units as a consequence. [31]

The apartments were very modern concrete structures that were

rented furnished or unfurnished, for varying amounts of time. The

corporation began to sell them to individual investors in 1952

using J. Glover Taylor Real Estate as its agency. They were so

sturdy that many were stilled occupied in 2012. They are an

enduring tribute to B. B. McCormick. His corporation also built

the Ponce de Leon Raceway (horses) in Jacksonville for $3

million, the Jefferson Downs Raceway in New Orleans for $4

million, and a Kraft paper mill in Georgetown, SC for millions in

addition to private housing units at the beaches.

B. B.’s health continued to deteriorate. He had Parkinson’s disease and other ailments; his body was wearing out. He rejoiced when his brother “Townie” and sister-in-law Beulah came from Savannah, Georgia in the Spring of 1948 and settled in the Pine Grove subdivision of Jacksonville Beach. Townie he had been superintendent of the Bonaventure Cemetery for 37 years.[32] The newspaper showed a photo of the two of them standing together but he was hospitalized more than a month later having fractured his knee in a fall at his Jacksonville Beach home.[33]

Before he died on October 15, 1953, he had to spend much of his time in bed. One of his employees, Ollie Ferrell, would carry him downstairs and served as a chauffeur, with relief from James “Georgia Boy” Bass. He had a nurse, Millicent Koski, to help. An elevator was installed the house to help. Relatives and friends visited to bring him news and fellowship.

Much of the general contracting firm was for government projects—local, national, and foreign. The family corporation, run Ben and J.T. since the early 1940s, had the ability to build many levels of infrastructure. It built government-owned sewer and water systems and pipelines harbor facilities, bulkheads, seawalls jetties, piers, and electrical power plants to fight World War II. Whereas the federal government had normally spent $3 billion a year in the 1920s and $8 billion on 1936, the biggest New Deal spending year, it spent $98 billion dollars in 1945. The national debt was $42.97 billion dollars in 1940; by 1945, it was $240 billion dollars.[34] The post-war boom created consumer and state spending to meet the demands of the Baby Boom. The Cold War, begun by 1947, generated massive U.S. government spending. The Mayport Naval Station, which had become a Coast Guard station, was reactivated and expended. The Korean war, begun in June, 1950, demanded new expenditures as did the Vietnam War. The Florida portion of the Space Program at Cape Canaveral presented opportunities closer to home. B. B. McCormick & Sons won contracts for massive government projects for millions of dollars.

The following chart delineates many or most of the large

government contracts held by McCormick & Sons. The foreign

contracts were for WWII or the Cold War. It was created from a

typescript, author unknown, found in the Beaches Museum & History

Center archives.

Government Contracts

Large Government Contracts |

Dollar Amount |

Palm Beach International Airport |

10,000,000.00 |

Brooksville Army Air Field |

5,000,000.00 |

Bartow Air Force Base |

5,000,000.00 |

Avon Park Airfield & Bombing Range |

10,000,000.00 |

Sebring Air Force Base |

10,000,000.00 |

Buckingham Air Force Base |

10,000,000.00 |

Crystal Lake Airfield |

5,000,000.00 |

Jacksonville Municipal Airport |

10,000,000.00 |

Green Cove Springs Naval Air Station and Fleet Harbor |

15,000,000.00 |

U.S. Navy Airfield, Georgetown, SC |

5,000,000.00 |

Cecil Field Naval Air Station |

20,000,000.00 |

Jacksonville Naval Air Station |

10,000,000.00 |

Mayport Naval Air Station |

10,000,000.00 |

Jacksonville Navy Fuel Oil Facilities |

5,000,000.00 |

Parris Island Marine Corps Base |

5,000,000.00 |

Sanford (FL) Naval Air Station |

5,000,000.00 |

Corry Field, Pensacola |

4,000,000.00 |

Foundation and Marine Construction, St Johns River Shipyard |

5,000,000.00 |

Roads and Utilities, Camp Blanding, FL |

5,000,000.00 |

Graving dock, Havana, Cuba |

12,000,000.00 |

Recife ( Brazil), International Airport |

10,000,000.00 |

Mascio (Brazil) Airfield |

5,000,000.00 |

Bridges and Approaches, Veradero Beach, Cuba |

6,000,000.00 |

Highway construction |

10,000,000.00 |

TOTAL |

197,000,000.00 |

B. B. McCormick is an inspiring American success story; he was a boy of very modest means without a formal education but with intelligence and drive. He started work on foot when he carried the mail between Fulton and Cosmo, learned the timber business and became a millwright, and then progressed to general contracting. In 1918, he acquired the first two (Buck and Skinny) of the many mules he would own as he leveled sand dunes, built roads, dredged and filled and the many other arduous required. He grew his business into a large one employing as many as 1,500 people and operating in several countries. He relinquished more and more control of his corporation to his sons as his health worsened. He had to give up his beloved herd of mules when his sons mechanized the work but the sons took the business new heights. The family corporation he built was involved in space exploration. He was the foundation and inspiration for generations to follow.

The Beaches Museum and History Center of the Beaches Area Historical Society is the principal repository of the history of the beaches. I am indebted to the people who toil there to insure that beaches history is preserved. Special thanks to the director, Dr. Maarten van de Guchte, and archivist Taryn. She is a kind soul who was generous in making make newspapers, vertical files, newspapers, and photographs available to me. The file on B. B. McCormick is very small but we found material in other files.

Suzanne McCormick Taylor, a granddaughter of B. B. and Dora McCormick, gave me insights about her grandfather and proofread a draft of this work. I appreciate her help and friendship of more than 50 years. We were high school student council officers together.

Patricia McCormick Wainer kindly supplied with with materials.

Another friend and family member, Michel Oesterreicher shared information from her research notes.

Other friends connected to the beaches helped in numerous ways. Nath Doughtie and Robert Dorough supplied photographs. Nath loaned me a place to stay while doing research. Dorough, who lived next to B. B. McCormick from 1942 until 1953, provided insights. He was a frequent visitor to B. B.

Fellow historian H. B. Paksoy critiqued the manuscript.

My wife, Paula Crockett Mabry, could not have been more supportive.

I am responsible for this work, of course.

Sources

Beaches Outlook, The

Bruce, F. W. Arlington Past, Present and Anticipated.

Arlington, FL: Arlington Community Club, 1924.

Buker, George. Jacksonville: Riverport-Seaport (Columbia:

University of South Carolina Press, 1992).

"Civic Organizations, Public Officials And Individuals Joined In

Fight For Four Lane Super Highway To The Beaches," Beach

Boulevard Dedication Pamphlet.

Davis, T. Frederick. History of Jacksonville Florida and

Vicinity 1513 to 1924 . Jacksonville, 1925.

Doggett, Frank A. Biography of B. B. McCormick Is History of

the Beach, 1949.

Doherty, Herbert J. "Jacksonville As A Nineteenth-Century

Railroad Center," Florida Historical Quarterly 58:4

(April, 1980 ), 374-387.

Gray’s Atlas (Philadelphia, PA: O. W. Gray and Son,

1886).

Diane Hagan, “Beginnings of the Black Community in

Jacksonville Beach,” Student paper, University of North

Florida, 1975. Copy in Beaches Museum and History Center,

Jacksonville Beach, Florida.

Jacksonville Beach News.

Johnston, Sidney. The Historic Architectural Resources of the

Beaches Area: A Study of Atlantic Beach, Jacksonville Beach, and

Neptune Beach, Florida. Jacksonville, FL: Environmental

Services, Inc., July, 2003.

Laslett, Peter. The World We Have Lost: England Before

the Industrial Age (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons,

1965).

Mabry, Donald J. Uncovering African American Micro History. HTA

Press, 2010

_________. Yankee Engineer in Florida. HTA Press, 2010.

_________. World’s Finest Beach: A Short History of the

Jacksonville Beaches (Charleston and London: The History

Press, 2010).

Miller, Phillip Warren. Greater Jacksonville's Response to the

Land Boom of the 1920s, MA thesis, University of North Florida,

1989.

Ocean Beach Reporter.

Oesterreicher, Michel. Pioneer Family: Life on Florida's

Twentieth-Century Frontier. Tuscaloosa: The University of

Alabama Press, 1996.

Pablo Beach News.

Polk City Directory: Jacksonville. 1914, 1919, 1925.

Powell, Cleve. “A Jacksonville, Mayport and Pablo Railroad

‘Tour.”” OAI Newsletter. January,

2008.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Company, San Pablo

maps.

Smith, Ed. Them Good Ole Days at Mayport and the

Beaches. HTA Press edition, 2005.

Snodgrass, Dena. Dee-Dot Ranch and Twenty Mile House: A

History. 1973.

Sollee, Arthur N. Official dedication program for Beach

Boulevard and the B. B. McCormick Bridge. 1949.

Stratton , Sandie A. and Stacey A. Cannington, “From the

River to the Sea: Upwardly Mobile Minorcans and Florida's First

Beachside Development.” Florida History Online, a

University of Florida Web site.

Taylor, Virginia, “A Beach Resident Since 1919, McCormick

Has 68th Birthday, ”Ocean Beach Reporter,

April 13, 1945.

US Department of the Interior Geological Survey, 1932.

“United States public debt,” Wikipedia. Retrieved

January, 2012.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_public_debt