By Donald J. Mabry

Over a century ago, the coast from south Jacksonville Beach through Ponte Vedra Beach was unspoiled by humans until two men, George A. Pritchard and Henry H. Buckman, Junior, began mining the beach for the rare minerals of ilmenite, rutile, and zircon. They dug in the sand on the beach as well as the high dunes to the west. The sand on the beach was hard packed, making it easy to utilize machines. They built a mining camp called Mineral City where they and their workers lived and where their equipment and buildings stood. The beach was the only road to this isolated spot. The two men worked hard in their extensive sand mining operation. Then they sold their holdings to National Lead Company, a major paint manufacturer, which continued operating under the name Buckman & Pritchard until mining ceased to be profitable. Someone realized that the land could be developed as real estate. They called it Ponte Vedra. It makes a good story.

Children on sand dune, vehicles on the beach

Children on sand dune, vehicles on the beach

George Pritchard and Henry Buckman on a Mineral City dune

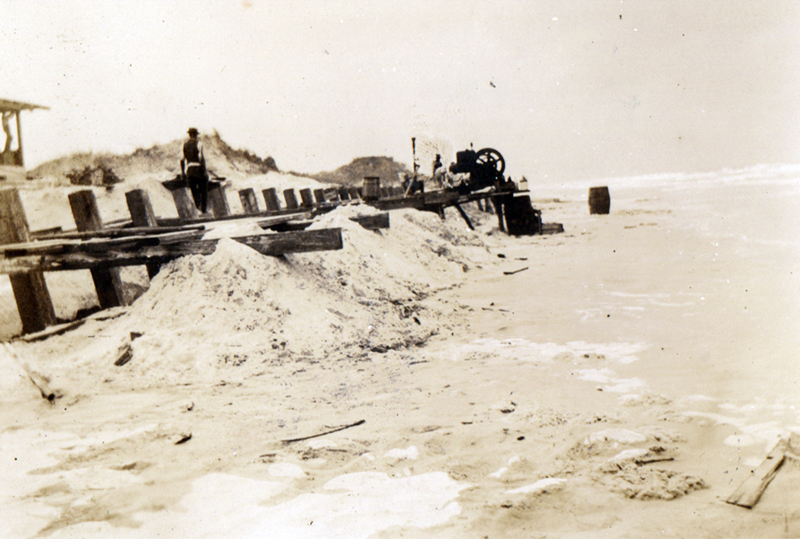

Bottom: Mining the beach, Atlantic Ocean in the background

Pritchard was born in Independence, Missouri on March 10, 1881, but grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana where he was close friends with the Wales family, especially daughter Nelle. In 1910, she lived on North Illinois Street with her father Edward A. Wales (60), a bookkeeper for Union Trust Company, her mother Ellen D. Wales, a housewife who was also sixty, and thirty year old sister Clara who worked as a secretary for a savings and loan association.[1] She and George used to ride a tandem bike to high school. Nelle said they always knew they would get married. He had a very good education as an engineer, having attended the Colorado School of Mines. Prit went to Costa Rica to work in a mine and returned, at age 26, to New Orleans, having sailed from the banana port, Puerto Limón, Costa Rica on board the steamship “Chickahominy” in the summer of 1907. He had a trunk, and a suitcase in his cabin. It was to the Wales house that he went to live. He used their shed as his laboratory.

He and Nelle finally married on January 1, 1917 when he was 39 and she was 33. She had been taking care of her parents. Her father was buried on May 4, 1925, her mother on November 5 the same year. George’s love became even more important.

They set up house in Mineral City, Florida. In 1918, he registered for the draft. The certificate identified him as blue-eyed with light brown hair. He listed Pablo Beach, Duval County. Florida as his permanent residence and also listed Buckman & Pritchard, Inc. in Pablo Beach as well. He said he was superintendent of mining and transportation.

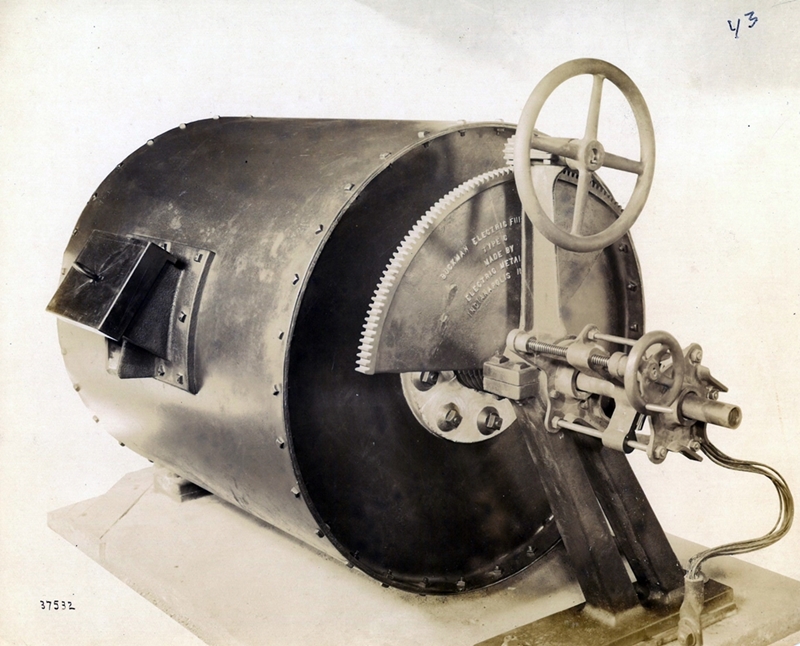

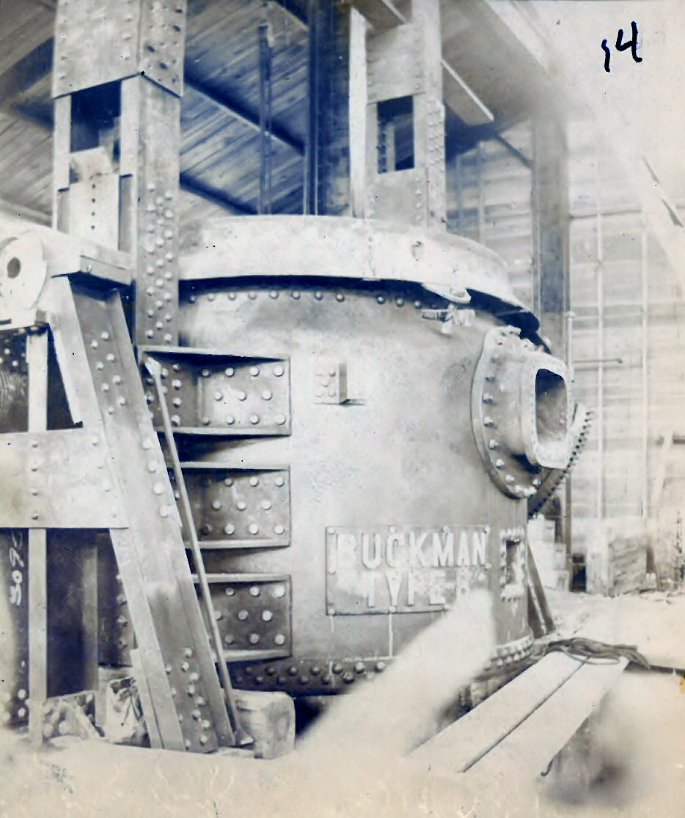

Indianapolis was also important in the life of Buckman, Junior as well.[2] He was the son of a prominent Jacksonville attorney who sent him to Harvard. He graduated with a cum laude degree in chemistry in 1908 at the age of twenty-two. His senior thesis was entitled “The Sands of Florida” in which he erroneously concluded that there were no valuable minerals in Florida sand. He then studied engineering at the Universities of Berlin and of Leipzig. One presumes that he went to Indianapolis to work with Pritchard, who was successful in his research, having applied for a patent on January 9, 1911 for an invention in the field of paints and painters’ materials. Buckman was living in a rooming house in Indianapolis at the time of the 1910 US Census. Buckman, with assistance from Pritchard, invented an electric metallurgic furnace in 1912; he submitted it for a patent in 1913and received it in 1914.[3] Below is a scale model.

Model submitted to the patent office.

Holland (left) and Pritchard (right) using Buckman furnace, 1914.

Buckman and Pritchard settled into partnership. Buckman married Mildred Regester of Indianapolis, and their son, Henry the 3rd, was born there on September 4, 1915.[4]

The two used sand in the casting of molten metal, some of which Buck’s family has sent from Florida. Pritchard noticed that some of the sand did not wash off easily and that it appeared to have metal in it. They collected enough to send it to a laboratory for analysis, a smart move. The lab found ilmenite, rutile, and zircon in it, all rare and valuable minerals. World War I was raging in Europe and these elements were extremely valuable in weapons of war. They knew the sand came from the southern east coast but were not sure of the location. After surveying that coast, they found a huge vein in the beach sands of Pablo Beach in southeastern Duval County and northeast St. Johns County. Birse Shepard, who interviewed Nelle Prichard in the 1960s, said it was four to five feet deep and four miles long. Others say the vein was five miles long of the seventeen miles of oceanfront they bought, some of which was north of the St. John County line.

Mining started in 1916, first in the “Friendship Vein” where concentration of ilmenite was high. Ilmenite, processed to titanium tetrachloride, was used in smoke screens, tracer bullets, and spotting shells. The war made it extremely valuable. Extracting it from the sand required machinery and men. Processing it required ingenuity; Buckman and Pritchard developed unique processes; no one else was mining sand for rare earths.[5]

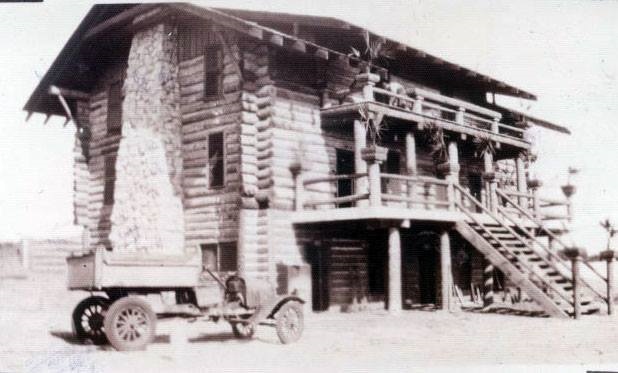

Mineral City was mostly a mining operation but it also was a home for those who worked there. It was not large but neither were Pablo Beach and Atlantic Beach to the north. Pablo Beach (later Jacksonville Beach) had only 249 residents in 1910 and 357 in 1920. Atlantic Beach had less than one hundred people in 1910 and only 164 people in 1930. The settlement had a post office to serve the workers and management. The company built housing for its employees. The best house was “Bonnie Dune” where the Pritchards lived until Buckman and Pritchard became a subsidiary of the National Lead Company. George Jeffers and his family then moved into it.[6]

Bonnie Dune in the dunes

Interior, Bonne Dune Lodge

Prit and Nelle Pritchard dining

Nelle and George Pritchard in Living Room, Bonnie Dune

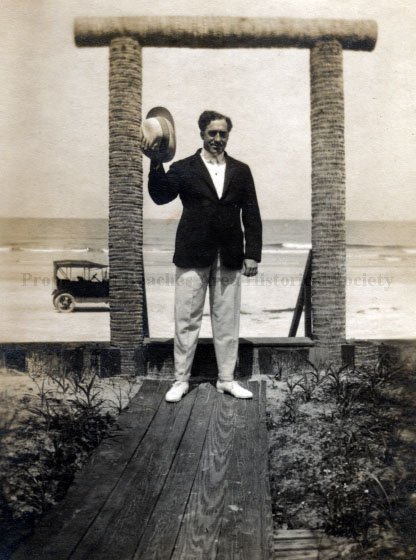

George Pritchard, c. 1919, at beach entrance to Bonnie Dune

Bonnie Dune Lodge. The Jeffers. Marion, George, and child Jeffers.

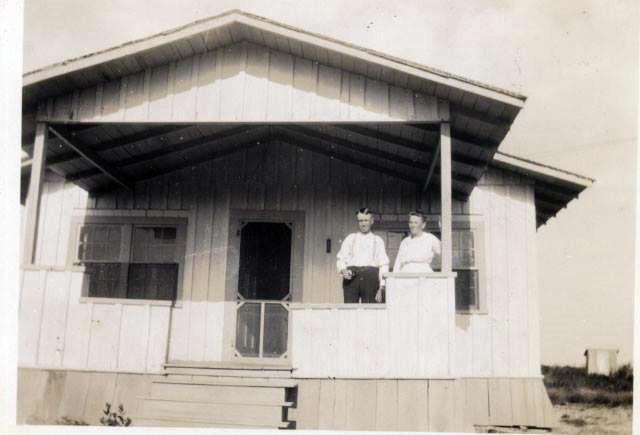

Other employees did not live as well. Rank and race determined where one lived. R. C. Root and his wife ran the commissary, a very important job.

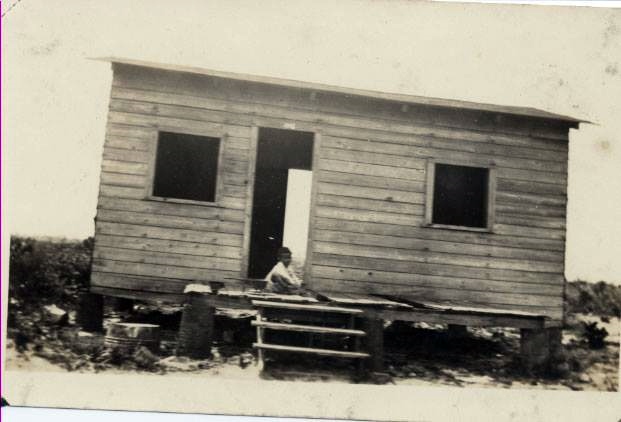

Mr. and Mrs. R. C. Root on the porch of their home

The Commissary ca. 1915

White Employee Housing

African American housing, Mineral City

Sand Plant, Mineral City Courtesy: Florida Photographic Collection

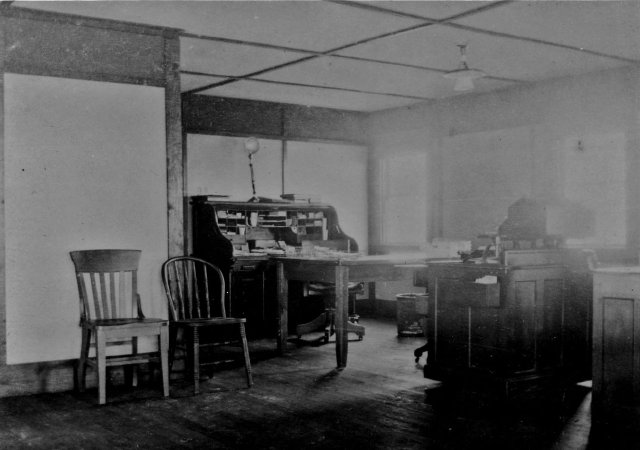

Office, Buckman & Pritchard

On the beach

Sand Cars delivered over 500 tons to the separation plant.

Sand Cars delivered over 500 tons to the separation plant.

Full Scale Buckman Furnace

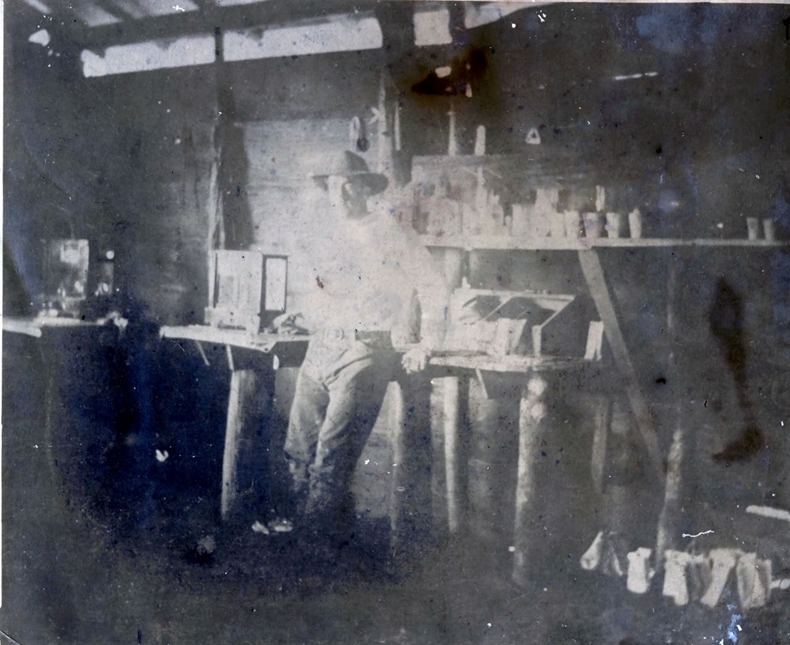

George Pritchard in workroom

George Pritchard in workroom

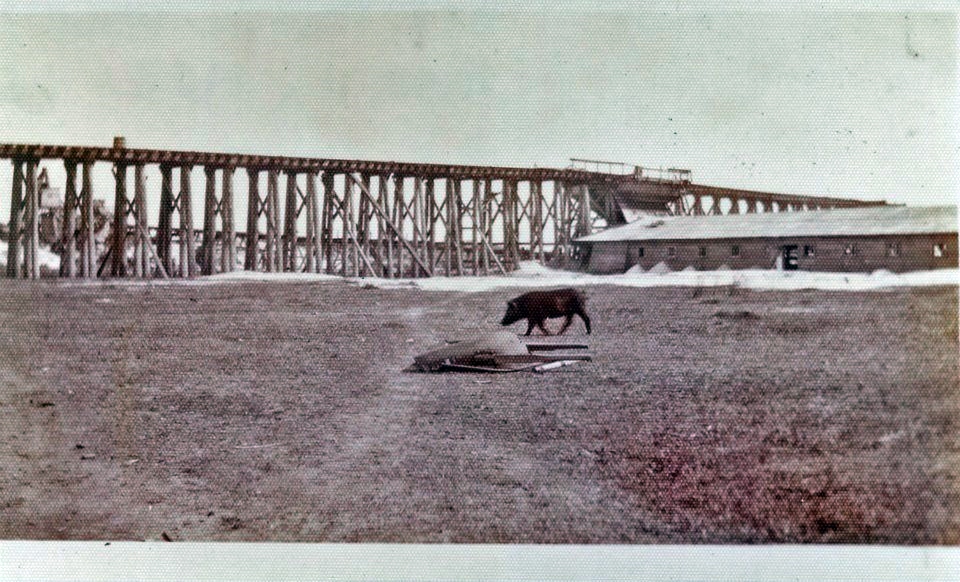

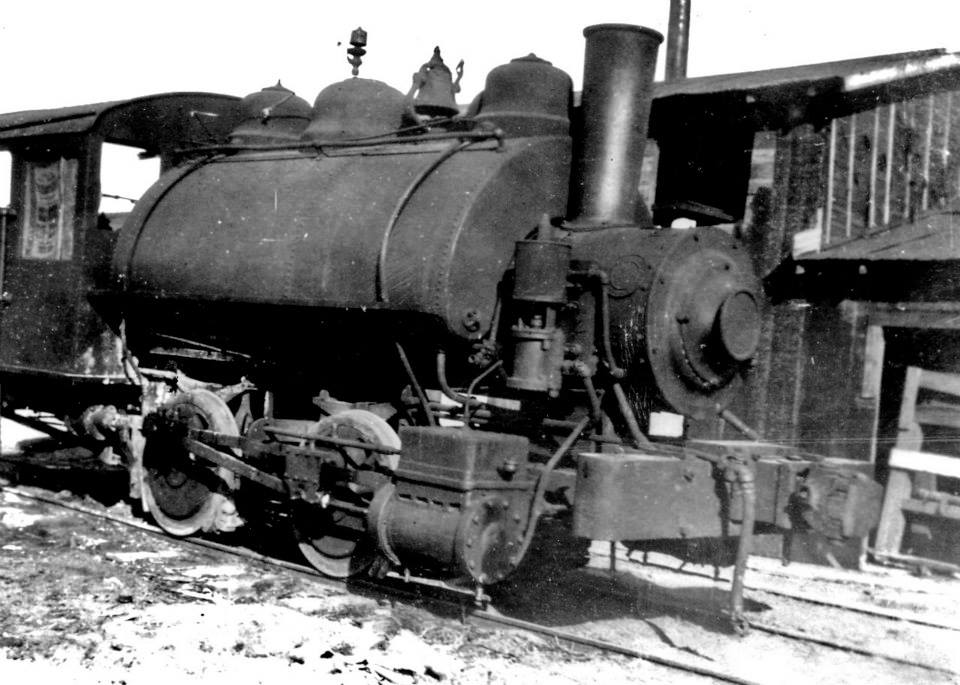

The plant covered acres and was connected to the Florida East Coast Railway at Pablo Beach via five miles of standard gauge track. From Pablo Beach, the minerals moved on the FEC Railway Mayport Branch to Jacksonville.

Dog waiting for the ore train to Pablo Beach, 1919

World War I began in Europe in August, 1914 and ended with the armistice on November 11, 1918. The United States was neutral until April, 1917 when it declared war on Germany and its allies. This war created demand for ilmenite. Buckman & Pritchard had a hard time when they first began mining in 1916. They dodged creditors according to Nelle Pritchard. The minerals were there but the process was complex and expensive. They had to invent new machinery to process the sand once it was mined. They began by mining and processing ilmenite, a needed war material. In the course of their mining, they obtained two patents. Frank Hess, describing some of their difficulties, wrote in 1921 in Mineral Resources of the United States, 1919:

In 1918, against the wishes of the Bureau of Mines and the U.S. Geological Survey, the federal government gave a contract to Buckman & Pritchard to furnish 410 tons of rutile at $90 a short ton of concentrate of 94% titanium dioxide (TiO2.) for manufacturing titanium tetrachloride used for making “smoke screens” in a war. The federal agencies argued that Buckman & Pritchard would be unable to produce large quantities of rutile in less than six months. The federal government advanced the corporation $11,000 in May, 1918. The company built an expensive plant with appropriate machinery to separate rutile and zircon. Buckman & Pritchard was unable to produce enough before the Armistice of November, 1918. It did manage to sell some to General Electric since the U.S. government no longer wanted it. Buckman & Pritchard lost money on the contract but a new federal law in March, 1919 allowed it to appeal and receive full compensation.[7]

In 1920, the company was sold to the National Lead Company, primarily a manufacturer of paint. Hess wrote that Ilmenite was shipped to Titanium Alloy Manufacturing Company in Niagara Falls, New York, a National Lead subsidiary. It controlled Buckman & Pritchard. Titanium Alloy refused to release production figures. Buckman & Pritchard also mined some rutile and zircon.

Buckman left Mineral City for Jacksonville where he created his own industrial and chemical engineering firm. He reported the change to the Harvard Alumni Bulletin in1922, and also the dissolution of Buckman & Pritchard, Inc. He must have meant his partnership with Pritchard since the corporation continued. Walter M. Philips was named manager in 1920. He enjoyed a successful career in Jacksonville. He authored the first statewide engineering examination, planned the city’s water supply, and engaged in development along the river. On May 3, 1929, he was elected President of the Jacksonville Historical Society. [8]

H. H. Buckman, Jr. [II] Courtesy: Jacksonville Historical Society

Pritchard remained active in Buckman & Pritchard of which he was Vice President. He asserted in Chemical Age in 1921 that zircon, ilmenite, rutile are not “rare earths” because his company is mining them in abundance. In a later issue of Chemical Age, Mineral City was explained to a national readership. Buckman & Pritchard of New York, New York owned miles of beach property, including Mineral City. The author of this article noted that the town had its own U. S. post office to serve the company and its workers. The company had built very nice cottages for the white population, some near the beach, some a quarter mile back from the ocean. It asserted that in the back of the plant, African American workers had better than average housing.

One got to Mineral City by taking Atlantic Boulevard to the ocean and driving south on the beach for four miles south of Pablo Beach. Fresh water was available at this ocean location from an artesian well which produced 2,000 gallons per minute. In 1921, the principal ores mined were ilmenite and zircon. Ilmenite was used to make a pure white paint with twice the covering power of white lead. Zircon is important in the manufacture of spark plug and electrical porcelains as well as many other uses. Buckman and Pritchard received two patents covering these minerals.[9]

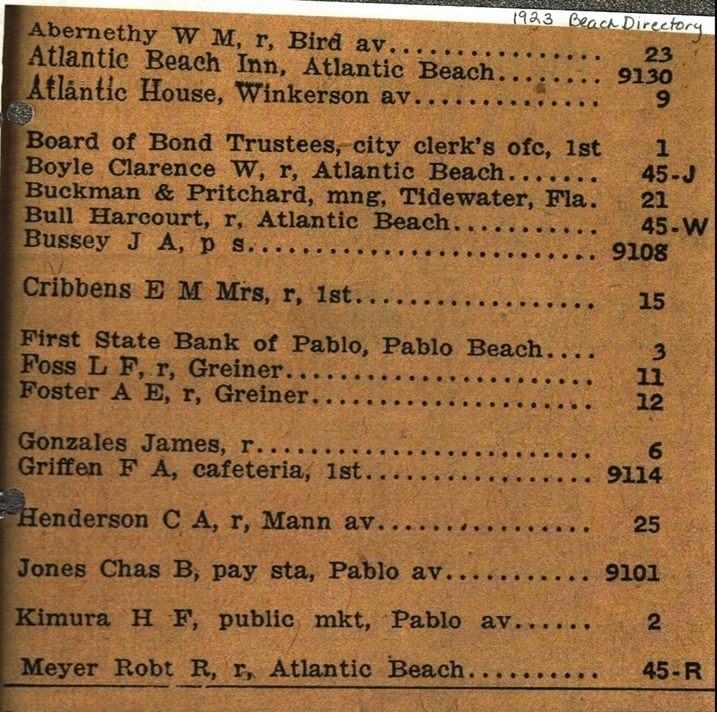

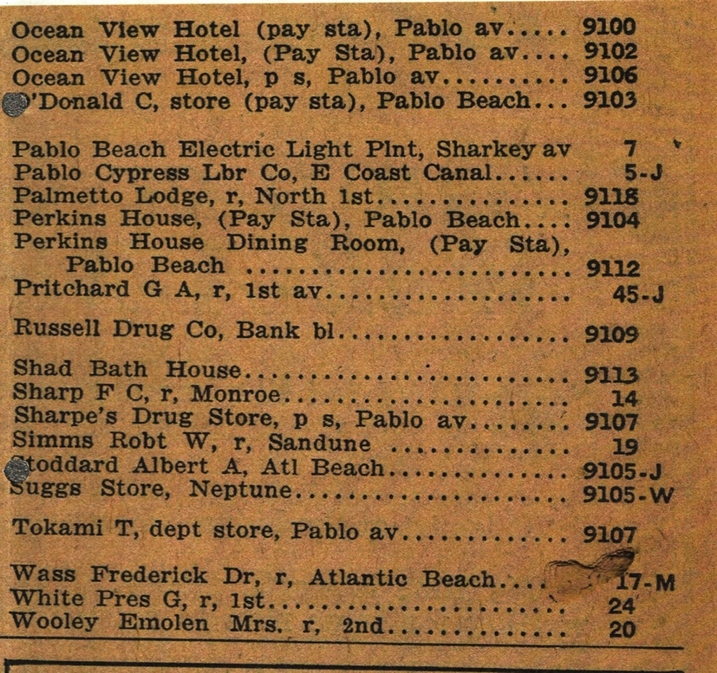

The 1923 Beaches City Directory showed important changes. Pritchard left Mineral City for Pablo Beach, living on First Avenue. His telephone number was 45-J. Buckman & Pritchard, the mining company, was located in Tidewater, Florida (wherever that was) and could be reached by the telephone number 21.

1923 Beaches telephone directory

Pritchard’s good life after he left the mining company is worth a digression from the main subject. He moved from Pablo Beach to Atlantic Beach. The Pritchards rented a house until their very large house on Thirteenth Street and the oceanfront was finished. In 1925, he was appointed to the brand new Atlantic Beach town council by Governor Martin and served as Vice President from the ?rst Town Council meeting on December 15, 1925 through August 11, 1926. The Governor also appointed the mayor and other town council members. Serving with him were Harcourt Bull as mayor; and W.H. Rogers, Charles Bell, Francis S. Mason, and Chalmers D. Horne as town councilmen.[10]

Patricia Pritchard, the servant Estelle, and Allen Pritchard, ca. 1925

Pritchard house on right.

His home, valued at $15,000 in 1930, was comfortable. He and Belle could entertain; he could continue his research. Living with the 49-year-old man was his wife Nelle, his son George, Jr. (called Allen) and daughter Patricia, his sister-in-law Clara Belt, and an African American servant named Frances Scott. It was in Atlantic Beach that they became friends of Elizabeth P. Stark of Mayport. Stark’s story is told in “Princess to Pauper: the Elizabeth P. Stark Legend.” The Beaches Museum owns a recording of Nelle and her daughter. Patricia Pritchard Finley, talking about Mrs. Stark with great fondness. Nelle was civic minded and was a newspaper columnist.

Nelle Pritchard

He remained productive. On October 13, 1931, Pritchard obtained a patent for built-in visors for motor cars. In the 1940 US census, he is listed as the president of a mining company earning more than $5,000 annually. On June 3, 1953, he was awarded a patent for a weather shield for automobile windows. He and his collaborator and friend, Leon E. Van Zile, received a patent in August 1966 for an “impregnating and coating apparatus”; he died in early November of that year. His widow, Nelle, applied for a patent on February 3, 1967 in her husband’s and Van Zile’s name for “Impregnating and Coating Compositions and Articles and Products Treated Therewith” which makes things more water resistant. For all patents, the patent office made sure that the object or process was unique, which took time. This Pritchard-Van Zile patent was granted in 1969.

George A. Pritchard

Mining the sand continued in Mineral City in the 1920s, but National Lead understood that the profit margin was getting smaller and smaller. The company reworked previous sites such as lagoons to extract zircon and rutile (titanium dioxide). Rutile was substituted for white lead in the manufacture of white paint. By 1927, the profits from Mineral City were almost gone. The company could not start mining in Jacksonville Beach because of its tourist industry. Someone (it isn’t clear who) decided to turn the mining town into an upscale real estate development with a golf course and private club. Some give credit to Walter Phillips who ran Buckman & Pritchard, National Lead’s subsidiary. He had been living in the Jacksonville area for years and knew the territory.

Left to Right: Walter Phillips, John Straughn, George Jeffers, and 2 unidentified employees

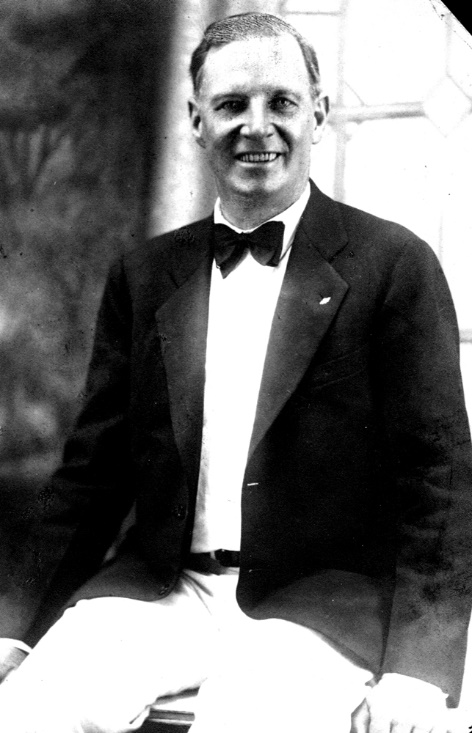

Walter Myles Phillips, ca. 1920

Walter Myles Philips was an amiable extravert who not only was the boss of Mineral City but was also active in the politics of Jacksonville Beach where he owned property. Property ownership gave him voting rights in 1928 regardless of domicile. Phillips, born in Michigan of Canadian parents in 1882, had been working for the Cummer Lumber Company before he took the job as the new manager of the mineral plant. His wife, May, was 30; their son Walter, Jr. was 12 and the only native Floridian. Living next to the Philips in Mineral City were the Jeffers. Francis Jeffers was the Superintendent of the sand plant. He, his wife Grace, son, and two daughters were all New Yorkers. The Jeffers occupied Bonnie Dune Lodge after the Pritchards left.

Philips rose quickly in Jacksonville Beach politics. On June 27, 1927, he announced his candidacy for the city council and won a seat in the July elections. The term was for two years but he ran for mayor the next year and beat J. A. Bussey, the perennial mayor, and W. H. Stormes. He wanted to attract conventions, beautify the city, and get the Atlantic highway [A1A] hard surfaced. He was ambitious for the beaches. He spoke to the Jacksonville Beach Board of Trade [Chamber of Commerce] urging its members to advertise the beach as a year round resort

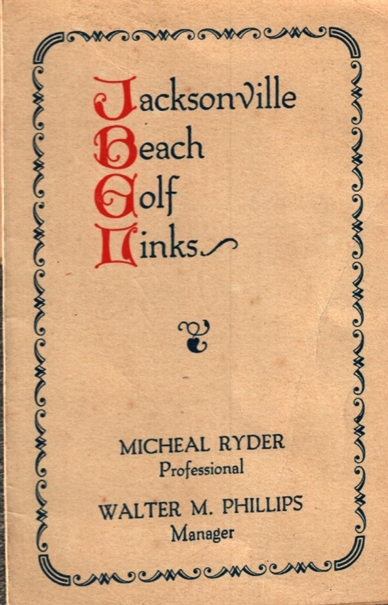

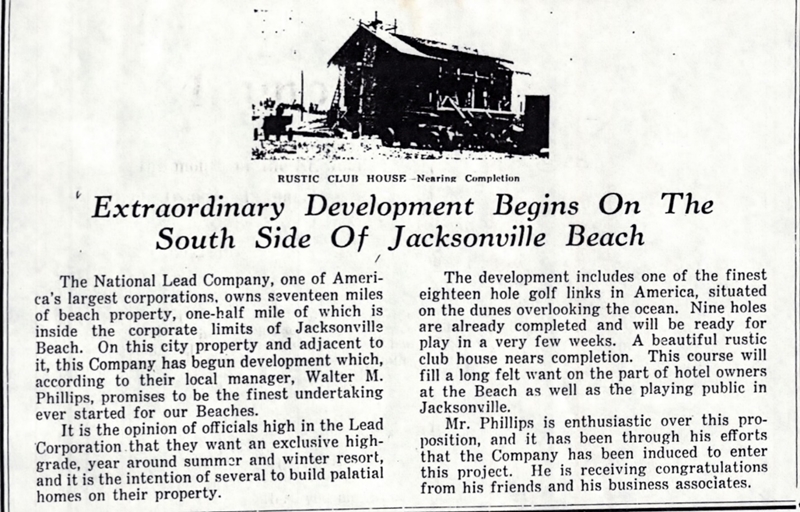

Phillips announced on August 1, 1927 that his company, Buckman & Pritchard, planned to build an 18 hole golf course and clubhouse facing the ocean. The course would be given to Jacksonville Beach. Philips hired D. C. Clark, a noted golf course architect, to design it and planned to have the first nine holes to be ready by summer, 1928. The first nine holes of the course were built by the end of 1927; he was the manager and Michael Ryder was the Golf Professional. The three-story club house had a large meeting room, a kitchen in the basement, a dining room, showers, lockers, and other traditional amenities, Phillips had an apartment on the third floor. The club house was located about where the Ponte Vedra Inn and Club is located. The Jacksonville Beach Golf Links golf course became the Ponte Vedra golf course.[11]

Building the golf course

The club house, 1927-28

Club House, 1942

On Saturday night, September 1, 1928, Mayor Philips, fell thirty feet to the concrete floor of the main auditorium. He had been sitting on the tiger skin on a banister when it slipped off and his body followed it down. He was entertaining friends at the time. He was taken to St. Vincent’s hospital in Jacksonville. The doctors could do little to repair the damage to his cervical vertebrae. He died on September 8, 1928.[12]

National Lead, through its Buckman & Pritchard subsidiary, continued Phillips’ efforts in St. Johns County. After all, it was in business to earn money and Mineral City was a very good opportunity because it was sole proprietor and the county government offered minimal supervision. The beautifully landscaped golf course by the sea expanded to eighteen holes. The designer made good use of the mining remains; some became attractive lagoons. Company officials renamed the area as Ponte Vedra Beach, a classier name than Mineral City. Real estate development is not a forte of a national manufacturing corporation so it used Telfair Stockton & Company of Jacksonville as its real estate agent. Telfair had been involved in building the Jacksonville & Atlantic Railroad to Pablo Beach. James Stockton assumed control after Telfair died and pursued the areas development with more vigor. On July 28, 1934, the Ponte Vedra Company was incorporated to create a high-grade, year around, summer and winter resort built around its golf course. Some National Lead officials planned to build palatial homes on the property but many were members of the Telfair Stockton Company. Jack Pate compiled a list of the first lot owners.[13]

Source: St. Johns County Public Records

GRANTOR: PONTE VEDRA COMPANY, Wm. F. Meredith, Pres.

| DB | PG | GRANTEE | FILED | LOT/BLOCK | |||||

| 105 | 121 | Robert B. & Ida Holmes McIver | 8/3/1934 | 3/1 | |||||

| 222 | Sara Hall Randle | 9/15/1934 | 5/2 | ||||||

| 107 | 280 | John Z. & Naniscah Tucker Fletcher | 5/16/1935 | 1/12 | |||||

| 285 | H.B. Merritt | 5/22/1935 | 2/12 | ||||||

| 290 | Gladys DeVore | 5/22/1935 | 3/12 | ||||||

| 295 | Thomas Fitch & Annette White King | 5/22/1935 | 4/12 | ||||||

| 300 | T. Knox Boardman | 5/22/1935 | 1/13 | ||||||

| 305 | Corrie C. Howell | 5/22/1935 | 4/14 | ||||||

| 310 | Joseph W. Davin | 5/22/1935 | 1/15 | ||||||

| 315 | James R. & Elizabeth Bryan Stockton | 5/22/1935 | 2/15 | ||||||

| 352 | Brown & Marion H. Whatley | 5/24/1935 | 3/15 | ||||||

| 357 | CORCO, Inc. (A Florida Corporation)* | 5/24/1935 | 4/15 | ||||||

| 366 | T.G. & Loca Lee Buckner | 5/27/1935 | 5 & 6/15 | ||||||

| 497 | Paul E. & Ida Klare Reinhold | 6/22/1935 | 3/11 | ||||||

| 564 | Colonial Homes, Inc. (A Florida Corp.)* | 7/10/1935 | 2/18 | ||||||

| 582 | Carl S. & Mary Swisher and | 7/13/1935 | 1/11 | ||||||

| H.K. & Mildred Smith | |||||||||

| 108 | 4 | Colonial Homes, Inc. (A Florida Corp.) | 7/23/1935 | 2/14 | |||||

| 9 | Colonial Homes, Inc. (A Florida Corp.) | 7/23/1935 | 1/18 | “ | |||||

| *Probably Arthur A. Corcoran of Palatka, | |||||||||

| who bought another lot in his name in 1936 | |||||||||

| (DB 110, PG 526) | |||||||||

So a sandy wilderness bordered by an ocean on one side and scrub land yielded its mineral resources to the profit to its owners for about fifteen years and was then transformed into a pricey real estate development. Membership in the Ponte Vedra Club controlled who could build or buy houses. Its remoteness in the first years discouraged casual visitors, helping preserve its exclusivity.

The genius of Henry Buckman and George Pritchard opened these miles of oceanfront to exploitation by mining and, thus producing “gold,” in a manner of speaking. The creation of Ponte Vedra produced even more “gold.”

Few living there know or care that their property used to be a sand mine.

Photographs

Unless otherwise noted, the photographs are from the large collection in the Beaches Museum. Many of them are snapshots taken by friends and relatives of the principal people in this history. There are so many that I could only use a few. Through the Museum’s Web site, one can search for these and other photographs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The personnel of the Beaches Museum and History Park/Center, especially Sarah Jackson, deserve praise for all they do to keep the history of the Beaches alive. MS Jackson as Archives & Collections Manager has been so very helpful to me. I live in Starkville, Mississippi, hundreds of miles from the Museum, but Beaches people, past and present, are generous with their time and resources so I can do this research.

Thanks to Taryn Rodríguez-Boette of the Jacksonville Historical Society.

My lovely wife Paula is an inspiration. She gives so much of herself to students and to our community.

© July, 2016 Donald J. Mabry

[1] U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1910, Indianapolis city, Marion County, Indiana,

[2] He sometimes is called Henry Holland Buckman II even though he was named after his father.

[3] “A Bibliography of the Roasting, Leaching, Smelting and Electrometallurgy of Zinc.” Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy. Columbia, Missouri, 1918. p. 255. Filed June 30, 1913; granted April 7, 1914. “Electrical furnace for Metallurgical purposes” filed by Henry H. Buckman, Jr. of Indianapolis; Bulletin: Technical Series. P. 255. School of Mines and Metallurgy, University of Missouri, 1918; and Chemical Abstracts, Volume 8, Issues 9-19, (April 7, 1914), p. 1708 for citation for Buckman’s electrical metallurgical furnace with a refractory hearth and electrodes supported above it by rotatable carrier. US Patent #1,091,764.

[4] Harvard Alumni Bulletin, Vol. 25, 1922. Page 46. Henry Holland Buckman, Junior was born in Jacksonville on October 26, 1886, making him five years younger than Pritchard. His father, Henry Holland Buckman, Senior (1858-1914), was a rich and powerful Jacksonville attorney and legislator. Senior’s Buckman Act (1905) consolidated the public institutions of Florida which, among other things, created the University of Florida. He is honored in Jacksonville with the Buckman Bridge. Buckman Senior died in 1914, about the time his namesake and Pritchard were beginning to mine the sands of Ponte Vedra. Junior, usually called “Buck,” maintained his strong ties to Jacksonville, where the 1920 and 1930 censuses found him and his family. By 1930, he and Mildred had two sons and a daughter. Senior was prosperous enough to send his namesake to Harvard and Europe. (October 26, 1886 – March, 1968). In 1920, Junior was living at Copeland Street, Jacksonville, with his wife Mildred. At age 82, he died on March 5, 1968, ten years after Mildred. For a short biography, see Jacksonville Historical Society, “Society’s first leader and his family were legends in city history,” January, 2016, http://www.jaxhistory.org/about-jhs/meet-the-team.

The patent is in Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office. (Washington: Government Printing Office. 1911), Volume 164. #53,770.

[5] Harald Elsner, Economic geology of the heavy mineral placer deposits in northeastern Florida. Florida Geological Survey, Tallahassee, 1977. United States Geological Survey, Mineral Resources of the United States, 1919. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922. Florida State Geological Survey, Annual report of the Florida State Geological Survey. University of Florida Digital Collections. Tallahassee, 1928, page 25. The report said that the recovery of ilmenite and monazite from Mineral City sand began in 1916. Florida is today (1928) the leading producer of ilmenite. The first commercial production of zircon was reported in 1922 and of rutile in 1925. Operations under name of Buckman & Pritchard, Inc. which is owned by Titanium Pigment Company, Inc. of Fulton Street, New York City, a subsidiary of National Lead Company. J. H. C. Martens, “Beach deposits of Ilmenite, zircon, and rutile in Florida,” Florida Geological Survey, 19: pp, 128-154. (1928), Tallahassee, Florida.

[6] From the Beaches Museum & History Center collection. Some are snapshots. Some were taken in the early 1920s.

[7] The first patent was on an electrical insulator (US 1370276 A) on October 10, 1919 and received it on March 1, 1921. On March 1, 1921, they applied for a patent which they received on January 2, 1923 for using zircon in high temperature applications. See Frank L. Hess, “Titanium,” Mineral Sources of the United States Washington, DC, Government Printing Office, 1922), p. 719.

[8] “Alumni Notes,” Harvard Alumni Bulletin, Vol. 25, 1922. Page 46. “Meet the Team,” The Jacksonville Historical Society January, 2016. http://www.jaxhistory.org/about-jhs/meet-the-team/.

[9] G. A. Pritchard, “American Enterprise Makes “Rare Earth” a Misnomer,” Chemical Age, Vol. 29, No, 2 (February, 1921), pp.45-46; Given the publication date, the article was written in 1920. Pritchard published another article in 1921. G. A. Pritchard, “American Production of Zirconium and Titanium Ores,” Chemical Age, Vol, 29, No. 11, (November, 1921), pp. 476.

[10] Pablo Beach News, March 28, 1925. S. S. Goffin of Jacksonville bought his oceanfront home just outside the Pablo Beach city limits for his summer home. For the1925 incorporation of the town, see Jacksonville Beach News, December 14, 1925. Donna L. Bartle, City Clerk, City of Atlantic Beach, email to Don Mabry, July 12, 2016 for his town council career. Birse Shepard errs in saying he was a mayor. Citizens elected a new town council and mayor on August 11, 1926.

[11] “Extraordinary Development Begins on the South Side of Jacksonville Beach,”

Beach Life, June 29, 1928; Maria A. Mange and David T. Wright, Heavy Minerals in Use (Elsevier, 2007), p. 1175. Florida Department of State, Division of Corporations, Document Number 129292.

[12] “Beach Mayor, Hurt in Fall, Still Paralyzed,” Florida Times-Union, September 3, 1928; Find a Grave Memorial# 70154459; Jack Pate, “Father of Ponte Vedra? Walter M. Phillips,” Tidings, Vol. 20, No 3, September, 1999.

[13] Jack Pate, First Lot Purchases in Ponte Vedra. Beaches Museum Archives, Sidney Johnston, The Historic Architectural Resources of the Beaches Area: A Study of Atlantic Beach, Jacksonville Beach, and Neptune Beach, Florida. Jacksonville, FL: Environmental Services, Inc., July, 2003.