Santa Anna, Antonio López de (1794-1876)

© (1997 and 2002) Donald J. Mabry

Santa Anna (born on February 21, 1794 in Jalapa, Vera Cruz and

christened Antonio López de Santa Anna Pérez de Lebrón) became one of the most famous

and infamous Mexicans of the 19th century. To U.S. citizens, especially Texans,

his reputation is unsavory. Mexicans tend to have mixed opinions. Most persons agree that

he was a man without integrity, an opportunist. From May, 1833 until August, 1855, the

presidency changed hands 36 times (average term was 7.5 months); Santa Anna was president

eleven times.

His background would not have suggested such a life. He was the son

of a respected Spanish colonial family; his father as a sub-delegate for the province of

Vera Cruz was a minor royal official. His family was wealthy enough to send him to school.

Even when his trouble making caused his parents to pull him out of school, for Antonio had

made it clear that studying held no interest, his father used his friendship and

connections with persons in the Spanish merchant community to apprentice the boy to a firm

of merchants in the city of Veracruz. Antonio, a bright and energetic youngster, could

have become rich had he stayed with the mercantile business but he found trade as boring

as school. He finally convinced his father to let him join the Vera Cruz Infantry regiment

on June 9, 1810. At sixteen, he became an army cadet. He had found his passion.

The young cadet, born a colonial Spaniard, initially defended the

Crown. Within months after joining and with little training, he was sent to fight.

On September 16, 1810, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla started Mexico's first effort to

wrest independence from Spain. In March, 1811, Santa Anna and about five hundred others

were sent by boat to Tampico. From there they were to march to fight Hidalgo's forces.

They were disappointed, for the priest had been captured elsewhere by the time they

arrived.

Since the unit was already in northern Mexico, a vast, arid, and

desolate region, where Indians nations were still resisting European and mestizo

encroachments, the royal government reassigned the unit to Indian warfare. Indian warfare

required cavalry troops with their mobility and ability to operate far from supply lines.

These cavalry units struck quickly and usually killed their prisoners, for they did not

want to be burdened with them. Executing Indians (who were often considered sub-human) and

traitors was accepted practice. When Santa Anna transferred to the cavalry, he was trained

in the most brutal tactics of the time. Frontal charges, risk taking, and the execution of

captured opponents would characterize his military tactics throughout his career.

A man of action, he loved soldiering. It was exciting, decisive, and

rewarding. He demonstrated his courage during a battle in San Luis Potosí province in

August, 1811 He was promoted quickly—to second lieutenant in February, 1812, to first

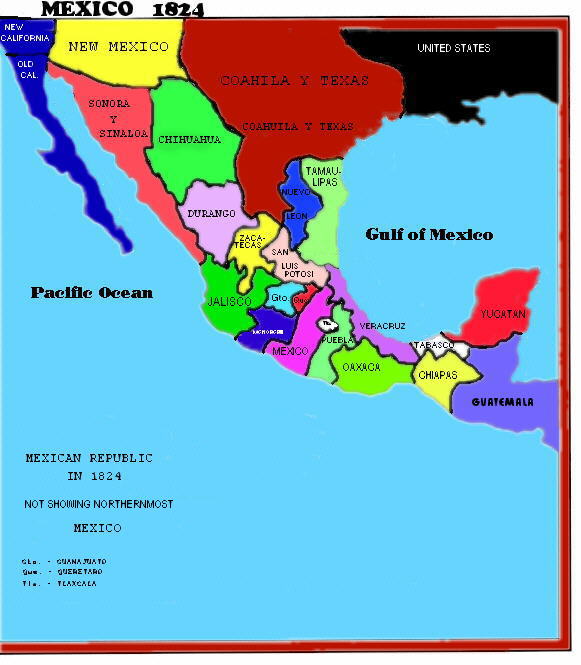

lieutenant before the end of that year. In 1813, his unit dashed to Coahuila-Texas

province to suppress a rebellion there. They took no prisoners.

Being an officer also carried special privileges. During his first

tour of duty in Texas he stole money from his unit's funds to pay his sizable gambling

debts. Caught out, he was reprimanded, told to restore the funds, and, in 1814, quietly

sent back to Vera Cruz. His fellow officers took care of him, for they did not have to

obey civilian law. They enjoyed the fuero militar (military privilege), which meant

that only fellow officers could punish them for peccadillos or crimes. Officers protected

one another not only on the battlefield but also against other

"enemies"—civilians and common soldiers. His officer status and uniform also

helped him philander, a personality trait which emerged early in his military career. In

1816, he was promoted to captain.

Although from a good family and holding a commission in the royal

army, his life might have been insignificant had it not been for the collapse of the

Spanish Empire. Military duty in New Spain, as Mexico was then called, consisted mainly of

occasional campaigns to suppress Indians or to restore order after a tumult had begun.

Royal rule was not so much by force but by allegiance to the Crown. The colony stretched

south to Panama and north to present-day Oregon, an area too vast for the Crown (and,

later, the Mexican government) to control.

The Crown lost New Spain by losing the support of colonial elites,

not through military losses. Father Hidalgo was defeated, defrocked, and disposed of, but

Juan Alvarez and Vicente

Guerrero led guerrilla bands which unsuccessfully fought for independence. The royal

army could not defeat them either. Most of the elite supported the Crown and most people

followed the lead of the elite. Agustín Iturbide

, a criollo royalist army officer,

deserted the cause of King Ferdinand VII when he realized that his fellow Mexican

conservatives would not accept the Spanish constitution of 1812 which Ferdinand had been

forced to reinstate in 1820. Alvarez, and Guerrero reluctantly supported Iturbide. The old

order was crumbling, giving opportunities to ambitious men such as Santa Anna.

Santa Anna, who had just been promoted to Lt. Colonel by the Spanish

Viceroy in March, 1821, climbed on the Iturbide bandwagon, becoming a colonel. When he

defeated a Spanish general in April, Iturbide promoted him to Chief of the Army's 11th

Division. Iturbide found the young colonel to be quarrelsome and opportunistic. Santa

Anna, in spite of reckless bravery, failed to dislodge the Spanish from their island

fortress in Vera Cruz harbor, the major reason he was sent there as military governor in

1821 and he so angered the local people by his constant forced requisitions of their goods

and money, that Iturbide had to reassign him to Jalapa. After he was instrumental in

capturing Vera Cruz city in October, 1822, Iturbide promoted him to brigadier general and

made him commander of the Vera Cruz province.

The young general, now twenty-eight, exploited his situation for

personal gain. He started acquiring land (and eventually would own a large hacienda). He

frequented gambling establishments and dallied with willing women. Having gone to Mexico

City, the young general courted favor with the Emperor by paying affectionate attention to

the Emperor's sixty-year old sister. Nevertheless, Santa Anna was never particularly

obedient to the Emperor. Iturbide solved that problem by sending Santa Anna back to Vera

Cruz as military and then civilian commander when Guadalupe Victoria rose up in revolt,

proclaiming that Mexico should be a republic. He didn't stay long because he once again

angered the locals and had to be recalled to Mexico City.

Iturbide's reign as emperor was short-lived, for he was never

popular and had to rely upon military support to stay in power. His generals began to

desert him. In December, 1822, Santa Anna defected to the republican cause, bringing with

him the custom houses revenues and the support of the wealthy Vera Cruz merchants who

disliked Iturbide so much that they were willing to accept Santa Anna's promises of

protection. The republican forces carried the day; Iturbide abdicated in March, 1823.

The new republican government was unsure how to handle Santa Anna,

for some of its members recognized how fickle his allegiances were. He was first sent to

San Luis Potosí state but then brought back to Mexico and put under house arrest when he

openly supported the federalist faction in the new government. Vicente Guerrero had him

released, reinstated as a brigadier general, and sent to distant Yucatán as military

commander. His aid in the defeat of Iturbide was valued. By mid-1824, however, he was in

trouble with the central government once again for he unilaterally declared war on Spain

and tried to invade Cuba! He was ordered back to Mexico City and put in charge of army

engineers, a post so boring that Santa Anna quit and went home to his estate near Jalapa,

Vera Cruz in 1825.

Santa Anna married fourteen-year-old Inés García [or Inés Garate,

the records aren't clear], daughter of a prosperous Spaniard and sired four children. He

acquired more land and became a prosperous gentleman farmer. Even with his marriage, his

children, his gambling, and his wenching, life was boring. He missed the military life and

he was no longer a national political factor. To play a role in the political activities

of the nation, he joined a Masonic lodge, for they provided the organizational basis of

the political factions.(1) York Rite lodges tended to be

liberal while Scottish Rite lodges tended to be conservative. Santa Anna joined a York

lodge and bought a Yorkish newspaper, but, when the power of the liberal government waned,

he quietly joined a Scottish Rite lodge. As a major landowner and a general, his normal

loyalty would be to ally with the wealthy and privileged, but his immediate concern was to

be on the winning side in any battle. Switching allegiance never troubled him.

He had ample opportunity in the ensuing years; Mexico lacked

political consensus and power was seized by force of arms. Santa Anna fought for President

Victoria and helped put down a conservative rebellion in 1827-28 led by vice president

Nicolás Bravo and the Scottish rite Masonic lodges. He was named governor of Vera Cruz as

a reward. In the 1828 elections, however, the states elected the conservative Manuel

Pedraza as president and the liberal Vicente Guerrero, the incumbent government's

candidate, as vice president. Santa Anna drove Pedraza from power. Guerrero became

president with the conservative Anastatio Bustamante as vice president. Santa Anna was

promoted to division general, the highest military rank. Santa Anna then won national

acclaim in September 1829 when he defeated an invading Spanish army at Tampico. The next

month he returned to his home and, in early 1830, resigned his political and military

assignments. Guerrero refused to discard his wartime emergency powers; his conservative

vice president, Anastasio Bustamante overthrew him in 1830, imposed a dictatorship, and

persecuted liberals. Guerrero, the old independence warhorse, was executed in 1831. The

hue and cry following this barbarous act told Santa Anna which side would win. In 1832,

calling himself a liberal, he raised an army and overthrew the government. Then, feigning

illness, he returned home to Jalapa to await the 1833 presidential election. He knew that

he was the logical choice to govern the troubled land, for he was the most popular and

powerful man in the country.

Santa Anna won the presidency in 1833 as a Liberal with Valentín Gómez

Farías as his vice presidential candidate, but governing little interested him. Or

perhaps he realized that the Liberal program would be controversial. Regardless, he

pleaded illness and went home to Jalapa, leaving Gómez Farías as acting president.

Conservatives revolted when Gómez Farías, through the "Laws of '33," which

ended special privileges; Santa Anna suppressed the rebellion. Liberal efforts to

dismantle the vestiges of the colonial past brought even stronger Conservative protests,

so much so that Santa Anna returned to the presidency in 1834, sent the Liberals and their

"Laws of "33" packing, and established a dictatorship. Conservatives

replaced Liberals in state government. He again pleaded ill health in January, 1835, and

returned to Jalapa, only to have to lead an army into Zacatecas to suppress another revolt

in May. Returning to the presidency once again, he abolished the constitution of 1824,

abolished state governments and put them under military control, made sure that only the

wealthy could hold public office, and repressed dissent In 1836, the ultraconservative

"7 Laws," which became the constitution. It made sure that only the wealthy

could hold public office, and abolished state governments, turning them into military

departments. Dissent would not be tolerated, for it threatened to destroy the nation.

Although a number of Mexicans protested, only those in distant Coahuila-Texas found a

successful means to resist. They and their illegal alien allies from the United States declared independence from

Mexico.

Texas had been a long-term problem for the Mexico government.

Located on the northeastern border, it was difficult to govern, for one had to cross

hundred of miles of arid and semi-arid land before reaching the fertile lands of

northeastern-most Mexico. In the colonial period, the Crown had established a fort and

mission (the Alamo) in San Antonio as a defensive measure. By the 1820s, however, the

cotton boom in the U.S. meant that U.S. citizens were infiltrating across the unguarded

border Mexico to acquire cheap land in Mexico. In an effort to forestall the

"Americanization" of Texas, the Mexican government granted land to a group led

by the Austin family

on condition that the members become Mexican and Roman Catholic. The effort failed, for

both legal and illegal immigrants violated the law. By 1835, the illegals vastly

outnumbered Mexicans and many wanted Texas to be part of the U.S., from whence they had

come. Exacerbating the situation was the 1829 Mexican law outlawing the keeping of humans

in captivity. Texans ignored the law with impunity for no Mexico City government could

enforce it. The Santa Anna government, certainly no friend of civil liberties and

democratic procedure, seemed to have the will to enforce the law. Texans revolted in 1836,

aided by foreign adventurers from the neighboring United States.

Santa Anna lost the Texas war for independence and his presidency.

His earlier experience in Texas had been against bandits and Indians and executing

prisoners was routine procedure. In the 1836 Texas campaign, however, he faced men who had

military experience in the United States and who were reinforced by volunteers from that

country. When the traitors and foreign revolutionaries inside the Alamo refused to

surrender, Santa Anna told his troops to take no prisoners. Later, at Goliad , he ordered the execution of

captives. These acts goaded the Texans and their allies to fight harder and brought more

aid from the U.S. Underestimating his opponents, Santa Anna failed to post sufficient

sentries, saw his encampment overrun by Texas soldiers, and was captured. To obtain his

release, he signed two treaties, recognizing Texas independence and promising never to

fight Texas again. The loss of Texas cost him the presidency, for he returned in disgrace.

His assertions that the treaties meant nothing because he had signed under duress and only

as a private citizen carried little weight. Mexico repudiated the treaties but the U.S.

recognized Texas independence in 1837; Mexico refused to do so.

The national government of Mexico was in disarray and ineffective.

The national elite saw politics as "winner take all—loser lose all"and wouldn't

compromise. Local political bosses controlled their own regions and the central government

had scant ability to enforce its will. Foreigners saw the country as easy pickings.

The French invaded Vera Cruz city in 1838 to collect debts owed by

Mexicans to French citizens. Santa Anna won this "Pastry War" (a French baker

was one of the creditors) after other Mexican commanders failed. A French cannon ball took

off his left leg during a battle. He was a national hero again!

Mexico needed a hero, for the nation was deeply divided and the

government was collapsing. The Bustamante government was falling apart. Bustamante named

Santa Anna as acting president in 1839 so that Bustamante could lead an army to suppress a

rebellion in Tampico. Bustamante succeeded but not as quickly as Santa Anna when he

destroyed a rebellion in Puebla. Few could then doubt that the General was more effective

than the President. Santa Anna waited until 1841 before overthrowing Bustamante and naming

himself dictator, a post he held until 1845.

This presidency was one of his worst. He was vicious and

egotistical. To offset criticism, he had his embalmed leg paraded through the streets of

the capital to the shrine built to house it. He angered important segments of the elite,

the Church, and the army. In November, 1884, he didn't bother to ask Congress if he could

lead an army to Guadalajara to put down a rebellion there. His army deserted him and he

was captured by Indians, who asked the new government if it would like him delivered as a

tamal, cooked and wrapped in banana leaves! Perhaps because he had only been married a

year to his second wife, fifteen-year-old María Dolores Tosta, he was sent into exile in

Cuba instead.(2)

United States efforts to acquire large portions of Mexico provided

the means for Santa Anna to come home and lead the nation again. The U.S. annexed Texas in 1845

and the Polk administration supported the bogus Texas claim that the Rio Grande was the

boundary between Mexico and the U.S., a claim that would also give Santa Fe to the U.S.

Polk also wanted California. When Mexico refused to sell off some of its territory, Polk

prepared for war, sending troops into disputed territory on the lower Rio Grande, across

the river from Matamoros. Mexico countered with troops of its own. Shots were exchanged

and Polk amended his war

message to Congress to assert that Mexicans had attacked Americans on American soil.

The Polk administration was uncertain about its ability to beat Mexico and agreed to send

Santa Anna home, for he convinced Washington that he would be more reasonable than anyone

in Mexico. He convinced the Mexican government that he should lead the attack against the

Yankee invaders since he was the nation's most successful. Within a month after his return

in August, 1846, he was leading Mexican troops northward.

Mexico, not Santa Anna, lost the war with the

U.S., but leaders blamed him and sent him back into exile. Mexican leaders had failed to

create an effective national army. Forced to war by the U.S., the government had little

choice but to turn to Santa Anna. He was the only general who possibly could defeat the

well-trained U.S. army, but he had to build an army as he made his way north to face the

invaders. Disgusted with the government which had gotten the nation into this mess,

national leaders made Santa Anna president in December, 1846. The President-General fought

Zachary Taylor's troops in February, 1847 at Buena Vista. Neither side obtained a clear

victory but the Mexicans fell back. Other U.S. troops were also invading Mexico through

California and Vera Cruz. Santa Anna regrouped and fought again at Cerro Gordo but the

American kept coming until they captured Mexico City in September after defeating

adolescent cadets (Los Niños Heróicos) at Chapultepec Castle. The U.S. had also invaded

Mexico at numerous other points. Mexico was simply not capable of defeating the

well-trained U.S. army. Mexico, not Santa Anna, lost the war.

Disgraced by the loss, Santa Anna resigned and eventually went into

exile in Jamaica in April, 1848. While he watched from afar, the U.S. completed its

annexation of forty-five percent of his country, which many of his countrymen blamed on

him. Much of his Mexican property was confiscated. He lived in Jamaica until 1850 and then

in New Granada (Colombia) until 1853. He quietly built a new estate in South America and

waited until his countrymen so mismanaged the nation that they would let him return. He

did in 1853 as dictator.

The government was broke in 1853 and having difficulty in paying its

army; money needed to be found to maintain the regime. Santa Anna made a critical mistake;

he sold a portion of Mexican territory (La Mesilla or the Gadsden Purchase) to the hated

U.S. His Liberal Party opponents, who had been fighting him for years, mustered enough

support to overthrew him in 1855 and send him back into exile once more time.

Try as he might, he was never able to play an important role in

Mexican history again. The Liberal Party hated him and was strong enough never to need

him. When the French-backed Archduke Maximilian established an erstwhile Mexican Empire,

Santa Anna returned to Mexico in 1864, offering to fight the Empire. In 1866 and 1867, the

United States government, which supported the Liberal Benito Juárez against Maximilian,

enabled Santa Anna to return to Mexico. Juárez, who had been exiled by the old rascal,

sent him back to Cuba. The Liberals ousted Maximilian without him.

Only pity for an old man and the fact that Juárez died in 1872

enabled him to return home in 1874. He had been living in Havana and Puerto Plata, Cuba

during 1867-68 and then in Nassau until 1874. He wrote his memoirs as his health failed.

He always believed himself to be a patriotic Mexican and no worse than any of his

contemporaries. When the Mexican government finally relented so he could die on his native

soil, he moved to Mexico City where he lived, in part, on the charity of relatives and

friends. The almost blind, eighty-two-year-old man died on June 21, 1876.

1. See Paul Rich and Guillermo de ls Reyes, " Problems in the Historiography

of Mexican Freemasonary."

2. His second marriage (to María Dolores Tosta) was childless.

Santa Anna legally recognized and provided for his four illegitimate children.

REFERENCES

Antonio

López de Santa Anna Collection Benson Latin American Collection, University of

Texas-Austin.

Anna, Timothy E., The Mexican Empire of Iturbide. Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1990.

Callcott, Wilfrid Hardy. Santa Anna; the Story of an Enigma Who Once Was Mexico.

Hamden, CT, Archon Books, 1964.

Santa Anna, Antonio López de, The Eagle: The Autobiography of Santa Anna.

Austin, Pemberton Press, 1967.

Jones, Oakah, Jr., Santa Anna. New York: Twayne, 1968.

Johnson, Richard Abraham, The Mexican Revolution of Ayutla, 1854-1855.

Westport, CT, Greenwood Press, 1974.

Mabry, Donald J., "Antonio López de Santa Anna," Historic World Leaders,

5: North & South America, M-Z. Detroit and London: Gale Research, Inc, 1994,

756-760.

Meyer, Michael and William Sherman, The Course of Mexican History, 3rd Ed. New

York: Oxford University Press, 1987.