Taking a Carriage on the Grand Tour

by

Sharon

Wagoner

yardoftin@georgianindex.net

Postchaise by James Pollard

The round of visits to cities in France and Italy with the possible

addition of visits to Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands which made up the

itinerary of the Grand Tour served as a hands-on education for young noblemen in

the eighteenth century. These travelers were the first tourists; in fact the

term tourist is derived from the Grand Tour. Some of these travelers chose to

take their own coach with them. We today might like to take our own car when

possible because it is more familiar to us, but in those pre-insecticide days

there was always a risk of renting a carriage which was infested with fleas or

simply in poor repair. What was it like to take your coach with you on the

eighteenth century Grand Tour?

The carriage itself was generally pulled by a team of two to four horses

and might be a chaise guided by a postillion riding one of the lead horses or a

coach controlled by a coachman who sat on the box at the front of the carriage

and drove the team with reins. Carriages often had a roof of leather over a

metal frame which could be let down like a convertible roof in good weather.

They were high slung so as to pass over rough roads more easily. A carriage was

entered by a side door with steps that folded onto the coach floor. The interior

was richly upholstered with fabric and seats padded with horsehair with an

overlay of goose down filled squabs. The interior might include seats that

folded down into a travel bed and compartments for guns, liquor, a telescope,

and maps.

A complement of servants for a nobleman who intended to spend one to

four years traveling Europe on the Grand Tour would include two coachmen for

each carriage, a pair of grooms for each carriage, armed outriders, and a

tutor/guide at the least. Other possible servants might include a valet and a

secretary.

If the tourist started from London it was a day long drive to Dover with

stops every 8 to 10 miles to exchange the four horse team for fresh horses. The

coach traveled at a speed of about 8 to 10 miles per hour. At Dover the coach

would be hoisted onto a ship that must wait for a fair wind in the correct

direction to make the passage to a European port, usually Calais. The trip might

take only three hours with a favorable wind, but waiting a week for the wind to

blow in the proper direction was not uncommon. Dr. Burney, the music historian,

waited nine days in 1772 for good weather. In Calais, the coach was hoisted from

the ship onto the dock with a crane.

After an inspection and obtaining a passport horses could be leased and

the coach could follow the reasonably good post road to Paris with sightseeing

stops along the way. After a long stay in Paris for lessons in fencing,

etiquette, and a visit to the French court, the tourist must decide whether to

enter Italy via the Alps or by crossing the Gulf of Genoa.

Over the Alps

There were no coach roads through the Alps until the end of the

eighteenth century, so to cross the Alps the entire coach had to be disassembles

and packed over the mountains on mule back. The Mount Cenis pass on the route

from Lyons to Turin was the most traveled route into Italy. The tourists were

carried over the mountains by Swiss chairmen in a device like a chair without

legs mounted on poles. A Miss Wilmot, who was one of the rare women to make the

Grand Tour, reported that the Swiss chair carriers were

happy men who burst into song as they approached the Alpine villages.

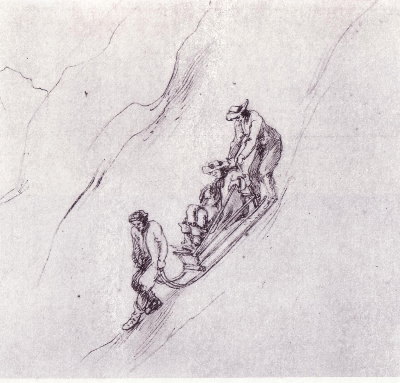

Sometimes tourists had the thrill of sledding down a

steep slope as Thomas Pelham did in 1777. Once in Turin the carriage was

reassembled and the tourist began the slow trip around Italy.

Pen and ink sketch of sledge in the Alps from Royal Library Windsor

Castle, England.

Pen and ink sketch of sledge in the Alps from Royal Library Windsor

Castle, England.

To

Italy by Sea

If the Grand Tour traveler chose to sail to Italy, he would first travel

to the south of France. The English were enchanted by the warm weather,

sunshine, and the fields of lavender, calling Provence almost Paradise. To sail

across the Gulf of Genoa a tourist engaged a fishing boat in Marseilles or Nice

and had the coach once again hoisted onto a boat. Then they embarked for Genoa.

The Gulf of Genoa was known for its sudden squalls. The specter of storm and

shipwreck or attack by pirates hovered over this route. However it could be much

quicker than the long arduous trek through the mountains, and Alpine passes were

closed in the winter. The tourist might cross safely but find himself quite

seasick as William Theed, the painter did. He complained in a letter to a friend

that he was seasick during all the crossing and for sometime afterward.

Lord Boyne and Companions

consult a map in the ship’s cabin.

Lord Boyne and Companions by

Bartolomeo Nazzari,

oil on canvas, National Maritime Museum, London, England

In the port of Genoa the coach was hoisted from the boat onto the dock.

Horses were obtained and the tourists began the round of Italian stops over the

excellent roads that were themselves Roman remains. The city of Rome with its

Roman buildings and Baroque churches, palaces, and fountains was a must see.

Naples with its beautiful bay, wonderful climate and the rediscovered Roman

cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum which were buried by the still active Mount

Vesuvius in 79 A.D. was a favorite destination. Exotic Venice, the gateway to

the East, was another usual stop in Italy.

Germany

and Austria

The roads in Germany and Austria were widely regarded as some of the

worst in Europe. Even on main roads to Berlin and Hanover the carriages would

often sink up to their axels in the muddy roadway. The inns were also

notoriously bad. Many a letter was written home from Germany pining for the

attentive landlord and excellent food of the English inn. On the other hand the

travel on the rivers was commodious and swift. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote

of her trip on the Danube River from Regensburg to Vienna in 1716 in glowing

terms.

The inns might be bad but the German courts were very hospitable and

always invited English tourists to dinner without inquiry as to birth or title.

Munich with its fine architecture particularly the Elector’s palace which all

the eighteenth century guide books particularly recommend was a favorite German

destination. Vienna was also particularly recommended by the guidebooks. The

Baroque Belvedere palace and the Schönbrunn palace were always visited.

The

Netherlands

Many Grand Tour travelers chose to either begin or end their tour in

Holland. The Dutch were the kings of trade in the eighteenth century and passage

home to England could be booked on one of their excellent merchants ships.

Travel within the Low Countries was facilitated by excellent roads. The

Antwerp-Brussels road was even paved. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote that the

whole country had the appearance of a garden. Holland must have seemed a garden

indeed with the whole coast from Leiden to Haarlem heavily planted with tulips.

Holland thus offered an excellent source of bulb plants and delftware china to

take home as gifts and souvenirs.

Grand Tour travelers also purchased many souvenirs such as pieces of

Roman art which might include vases and sculpture. The transportation of the

bulky purchases and safety in numbers meant that very wealthy tourists generally

took more than one carriage with them on the tour. The account book kept by Lord

Burlington’s head servant listed 878 pieces of baggage on their arrival back

in Dover. Many of the pieces of baggage would have been crates of paintings,

books, and antiquities. Other tourists of less exalted means tried to travel in

tandem with fellow travelers they met along the way.

England

and Home

After the Channel crossing, the carriage would be once again hoisted

onto the dock at Dover, England after years of travel. The wheels and harnesses

would have been replaced more than once by this time. The coach would then

convey the seasoned young adventurer back to his home, perhaps a learned man,

but both carriage and man would certainly be well traveled.

Sources

Black, Jeremy. The Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century. New

York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

________. Italy and the Grand Tour. New Haven and London: Yale

University Press, 2003.

Hibbert, Christopher. The Grand Tour. New York: G. P. Putnam’s

Sons, 1969.

McCausland, Hugh.The English Carriage. London: The Batchworth

Press, 1948.

071504