Source: MyFlorida.com

1895

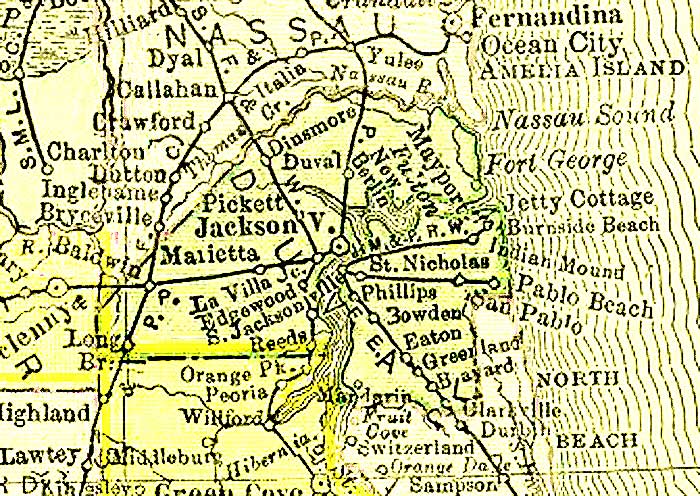

Duval County

1895

Duval County

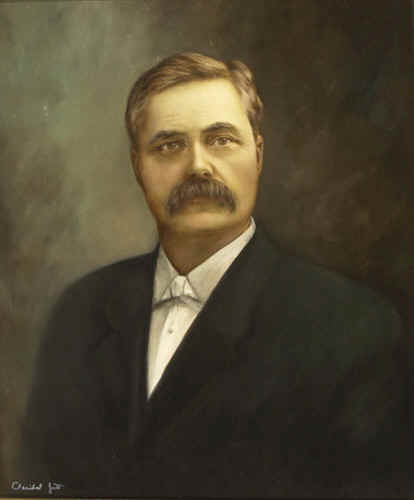

Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, Junior was born on the family farm on the St. Johns River in Duval County

on April 19, 1857. His family was prominent and wealthy. His grandfather, John Broward,

liked famous names. He named the first

Napoleon Bonaparte Broward and he also had Charles, Pulaski (from the

Revolutionary War), Washington (the first President), Montgomery (British

general), Maria, Caroline, Helen, Margaret, and Florida. He established a

school on his plantation on the north bank of the St Johns River and imported

teachers at a time when there were very few schools. The Browards were among the landed gentry, the

elite, of Florida.

Charles graduated from Harvard Law. Napoleon Senior was a dapper man who married

a New Hampshire Woman, Mary Dorcas Parsons, who had taught school in Mayport on

the south bank of the St Johns River at its mouth. She was sixteen, a proper age

for a bride in those days. She bore Napoleon Senior eight children—Josephine,

Napoleon Junior, Montcalm, Mary Dorcas, Emily, Osceola, Hortense, and

California. They all lived on land on Cedar Creek given to Senior by his

father.

Napoleon Junior had a pleasant, carefree life

surrounded by family and servants until Florida tried to

secede from the United States early in 1861. The United States government was

not about to allow that. Broward Senior thought it a great idea, however, and became Captain

Napoleon Broward when he raised a militia company. It cost the Browards dearly. When

the United States Army and Navy invaded Florida, Confederates adopted a scorched

earth policy but to no avail. The Browards' farms were burned. The United States

Army occupied Jacksonville. For many, that most of the soldiers were black

really roiled the supporters of slavery.

After the war, the Browards were

reduced to a hard scrabble existence. Eight-year-old Junior and even younger

Montcalm did heavy manual working, trying help the family survive but they were

not very good farmers. Life was tenuous, a far cry when they were rich and

powerful by Duval County standards. The mother died in February, 1869. Although

she hadn't enjoyed good health for years, Mary Dorcas Parsons Broward had been a

mainstay of the family. Broward Senior soon moved the family to his brother's place, the

former John Broward plantation, where there were aunts to raise his children. He

began working in Jacksonville, trying to feed and clothe his brood. But he

mourned Mary Dorcas excessively as well as the destruction of the lfe he had

known before 1861. He died in December, 1870. His children were orphans.

Uncle

Charles moved to Jacksonville to practice law; he was eventually successful but,

the aunts took their nieces and moved to Jacksonville, leaving Junior and Montcalm

on the farm for most of 1871. They futilely tried to make it pay. Broward Junior, now the only Napoleon Broward, and Montcalm moved to their mother's brother's home, Joe

Parsons,

and worked in his lumber camp at Mills Cove. It was hard, dangerous work. No fancy

clothes or speech there but getting one's hands scraped and dirty, aching

muscles, dangerous saws, and long hours. Whatever memories Napoleon had ever had of being in the elite were

long gone. He was working class. In the Fall, 1873 he and brother moved to Mill Cove, went to school, and worked on a

farm.

Napoleon got lucky in the Spring of 1875 when he started working on Joe Parson's steamboat.

He starting learning the river and its ways. Until his death he would always be

something of a river rat. In the Fall,

he returned to

school but in New Berlin, boarding with the lighthouse keeper. The

lighthouse was in the

river, 200 feet from Dames Point. Today the exquisite Napoleon Bonaparte

Broward Bridge, commonly known as the Dames Point Bridge, would be built there. New Berlin was

a bustling, important river town where trade occurred and ships were built. Captain David Kemps

built and owned boats including the Kate Spencer, a vessel important to

the Jacksonville area and to Napoleon. He worked on the ship and became friends with

Georgiana Carolinas Kemps, the captain's daughter.

When he finished school (what passed for high school) in 1876, he

signed on as ship's mate and he

traveled to New England where he had Parsons relatives. The seafaring tradition

of New England dated from the early 17th century; he learned more than he could

ever have learned on his river. He returned to Florida in 1878. By 1882, he was working on a

sea going tugboat; in December, he became a partner with Kemps. He made a great

career move in January, 1883 when he married

Georgiana Carolinas Kemps. The couple moved to the mouth of the river to Mayport,

a fishing and lumber village. There, they lived with Mrs. Arnau at her boarding house. In

May, Napoleon applied

for a pilot's license so he could lead ships over the treacherous, shifting

sandbar at the mouth of the St. Johns River. Pilots charged hefty fees and

Napoleon made money. He seemed set for life.

Then came tragedies. In the summer of 1883, his beloved sister

Josephine died . The couple left the river and moved into her house in Jacksonville.

Then his wife

Georgiana died in childbirth

on October 29, 1883. Then his son, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, III, died on December 16. Life

once again was cruel.

In June, 1884, Broward went north but came back in the late Fall. He

piloted his father-in-law's steamboat, David Kemps. Then he became

partner on the Kate Spencer. Captain Broward as he was now known,

prospered from tourism, hauling cargo, and carrying mail carrying to Mayport by July, 1885.

The Kate Spencer was big and well-furbished so tourists sough it out.

That the captain, who live ion the boat, was a big, strapping, handsome 29-year-old

man was also a draw. One young lady snagged him, quietly but steadily reeling

him in over several months.

He married

Annie Douglas on May 5, 1887. They lived in Jacksonville. In October, 1887,

he bought a small lumber yard and gristmill from George A. DeCottes in the city

but he loved the river. He hired someone to run it while he continued to work on

the river where he could earn more money but also smell the water, wind, flora,

and fauna. He was happy, prosperous, and respected.

Then came the notorious year of 1888. Jacksonville was scandalized by a prisoner escape which occurred because the

sheriff had moved the prisoner from the county jail to an office in commercial

building. The prisoner walked out while his guards were asleep on February 2, 1888.

Uproar and furor followed. Governor Perry asked for and got the sheriff's resignation.

The Democratic Party executive

committee recommended Broward who was appointed on February 27, 1888.

Broward went

after gambling in the city and stopped most of it. Jacksonville was, after all,

a port city so people, locals and visitors, liked to take chances. The

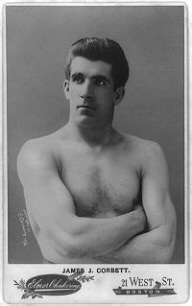

Corbett-Mitchell heavyweight championship fight was a real challenge, however.

Mayport, the little village at the mouth

of the St. Johns River in northeast Florida, played a significant role in two

fights by “heavyweights” in the winter of 1893-94. One is well-known,

drawing international attention; the other was not. Victory for one; defeat for

the other. Both are intertwined.

“Gentleman Jim” Corbett fought the English heavyweight champion,

Charles Mitchell, for the heavyweight championship of the world on January 25,

1894 in Jacksonville, Florida. The fisticuffs were held in Moncrief Park under

the auspices of the Duval Athletic Club. The club sold tickets for $25 each to

pay the purse of $20,000 and meet expenses. The DAC had pulled off a coup in

getting this championship match scheduled for Jacksonville both because other

places wanted this “Super Bowl” of boxing and because the illegal fight met

stiff resistance.

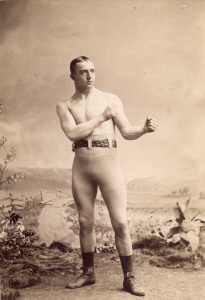

Jim Corbett Charles

Mitchell

Corbett trained at Mayport less than twenty miles by train from the south

part of Jacksonville. He and his crew rented the summer home of Claus Meyer and

almost got arrested when one of Corbett’s aides forgot to pay Meyer until he

threatened arrest. Mitchell trained in St Augustine, well over thirty miles

distant.

Both were distant from the furor in the state over the upcoming fight. The

opposition seemed insurmountable. Opposed were Governor Mitchell I.

Mitchell, Jacksonville Mayor Duncan U. Fletcher, Duval Country Sheriff Broward,

churches and moralists, and the Second Battalion of Ocala Rifles which the

governor sent to Jacksonville. They saw betting immoral and feared that the

match would bring riff raff, whores, gamblers, the wrong kind of tourist, and

such to the city. They feared violence.

Pressing public officials seemed to

work. The Governor said no. The Mayor and the Sheriff Broward each said no. One suspects

they were not that opposed but were afraid to say otherwise. Sheriff Broward

didn’t complain that much when Circuit Court Judge H. M. Call issued an

injunction to prevent him from attaching the Duval Athletic Club’s property or

enter its grounds. Governor called up troops (the Ocala rifles). Groups tried to

get the railroads of H. B. Plant and Henry Flagler not to transport any

spectators or gamblers or whores or boxing people to Jacksonville. Free

enterprise prevailed, however. The railroads were not about to forgo profits.

They refused to accept the argument that it was their moral duty and they should

act as government. Moreover, they refused to transport the troops without cash

payments in advance. The Governor conceded. When he threatened martial law in

Jacksonville to prevent the Corbett-Mitchell fight, he went too far. Public

opinion turned against him. Prominent merchant L. Furchgott protested; the

business community had joined the pro-fight crowd. The troops that came were

booed as they marched down Bay Street. As it turned out, their presence

was a charade, a way of saying the Governor was serious about maintaining public

order. The fight would go on.

One who came to Jacksonville was a blond New York City woman who was

wintering in Florida went to Mayport with her Jacksonville cousin to visit the

training facilities of Jim Corbett. No doubt, they probably also wanted to see

this very fine example of male beauty. As the New York Timesreported on

December 25, 1893, “Corbett’s muscles stood out in perfect relief, and his

skin glowed with perfect health.” He was worth seeing. He sparred

and wrestled and ran. He weighed himself twice a day on the scales he used,

scales which had to be accurate to satisfy boxing rules.

Our heroine made the first of several bad decisions, ones that she would

lose the battle to maintain her dignity. She sweet talked the powers that be to

allow her to try Corbett’s scales, to become more than a spectator. And she

mounted them. Much to her horror, she weighed 138 pounds! Surely, she thought,

she couldn’t have gained weight on vacation in Florida; surely the scales were

wrong. She searched the tiny windswept, sandy village for another scale, one

that she was sure would show she wasn’t that “fat.”

>A little grocery store nearby had scales to

weigh its products, keeping them with hogsheads of molasses in a small annex.

The hogsheads had a trough below for the drippings when drawn off. The trough

was two by nine feet, more or less, and a foot deep. The annex was dimly lit and

its floor was lower than the main building. Our heroine fell into the trough,

for her eyes focused on the scales which would restore her reputation. But she

was stuck! She was too fat to get out of the tough either by herself or with the

help of the owner and his assistant. It took four men!

The defeated tourist, holding her head high, headed for the proprietor’s

house to get clean as small boys tasted her newly-acquired sweetness. She was

even heavier.

The other heavyweight, Gentleman Jim Corbett, won twice. The “scientific

glove contest,” as the DAC termed the match, was held in Moncrief Park in

Jacksonville before 1800 people. Corbett won in twelve minutes and became

Heavyweight Champion of the World. The purse was awarded; Corbett collected the

$10,000 he had in side bets; and the swells and “sports” settled up

according to their gamble.

Corbett and Mitchell were arrested for assault and battery. Corbett was

tried first and acquitted. The government gave up. The crowds left. The Duval

Athletic Club disbanded. Life in Mayport settled down. We don’t

know if the sweet woman ever recovered from the loss of face.

We do know that Broward became active in city politics as a liberal, a Straighouts, against the conservatives, the Antis,

in the

Democratic Party. The Republican Party had no clout because of Reconstruction

when it had forced Southern states to be more democratic and enfranchised African Americans.

The Democratic Party was the "white man's party" and most

whites did not want democracy. They wanted to rule.

The Jacksonville Yellow Fever epidemic of 1888 caused a political as well as

a mortality crisis. Jacksonville was a black city but white voters still

controlled but whites fled and the black vote was the majority in the November

elections. Broward and other Democrats lost. Broward, however, was appointed

again in 1889 after the victor was declared ineligible. State government would

change the rules so that only the Democratic Party, which was white, could win.

The US population census of 1890 reveals that the county contained only 26, 773

people, of whom 14, 878 or 55.6% were black. The number of white voters was

small since at least half were females and many were children. In other words, a

few thousand white men could vote.

Being sheriff did not prevent Broward from conducting private business.

In Florida at the time, mixing the two was allowed. He was elected Sheriff in 1890.

and built the Annie Dorcas with his brother and three

others. He always had business interests in addition to his being a full-time

public employee.

Black-white relations could get testy, especially when the majority tried to

assert itself. In 1890, the Duval County population was 11,895 whites and 14,878

blacks for a total of 26,773, 55.6% of whom were black. In 1900

there were 39,733 people in Duval County, the majority black, Jacksonville's

population of 28,429 in 1900 made it Florida's largest city. Blacks were 16,236

Afro American residents comprised fifty-seven per cent of the population.

On July 4, 1892. Benjamin Reed, a black teamster, and a white office worker, Frank Burrows,

began fighting which began because

Burrows made disparaging remarks about Reed. It was a hot 4th of July and those

working were hot and tired. Burrows wanted

them to finish their work at the Anheuser-Busch company and berated Reed,

calling him names. They fought with wooden staves. Reed killed Burrows and was

arrested and jailed.

Whites began talking of pulling him out of jail and killing him but black groups prevented it. Jacksonville was a majority black city. Broward heard

the rumor that a mob was coming from Mayport to avenge the death of their

neighbor Burrows. That night, Sheriff Broward wired Governor Francis Fleming to

send the militia to prevent a lynching. A Jacksonville unit was activated but it

did not appear to be enough for white and blacks mobs grew in size and

hostility. Broward got more troops from nearby towns, about 375 men, and a Gatling

Gun was placed at the jail. There was a skirmish between the anti-lynchers and the

Metropolitan [Jacksonville] militia with both sides firing weapons. One Private

and two black men were injured. The New York Times asserted that there never was

any intention to lynch Reed, just that a white firebrand had advocated it. The

African Americans took no chances. The presence of the troops and the statements

of their commander that no lynching would occur, plus a heavy rainfall, drove the

people off the streets on July 7th. Reed was tried, convicted, and sent to

prison. See "Shot Down By Soldiers," New York Times, July 7,

1892 for a contemporary account.

Broward was fair during this crisis. He prevented a black man from being

murdered, a likely event if he had not decided to obey the law and to get

reinforcements. Another sheriff might have acted differently since there was

obvious fear of the black majority in Jacksonville and Duval County. He

preserved law and order.

In the 1892 municipal elections the liberals, the Straighouts, took control. Broward's

friend John N. C. Stockton became city attorney. Stockton would eventually lead

the liberals. However, in 1894, the conservatives or Antis took control again after their fellow

conservatives in the state government intervened, accepting the Antis arguments

that the Straighouts had committed vote fraud, the same charge the Straighouts

made against them. Broward was fired as Sheriff and went back to private

business.

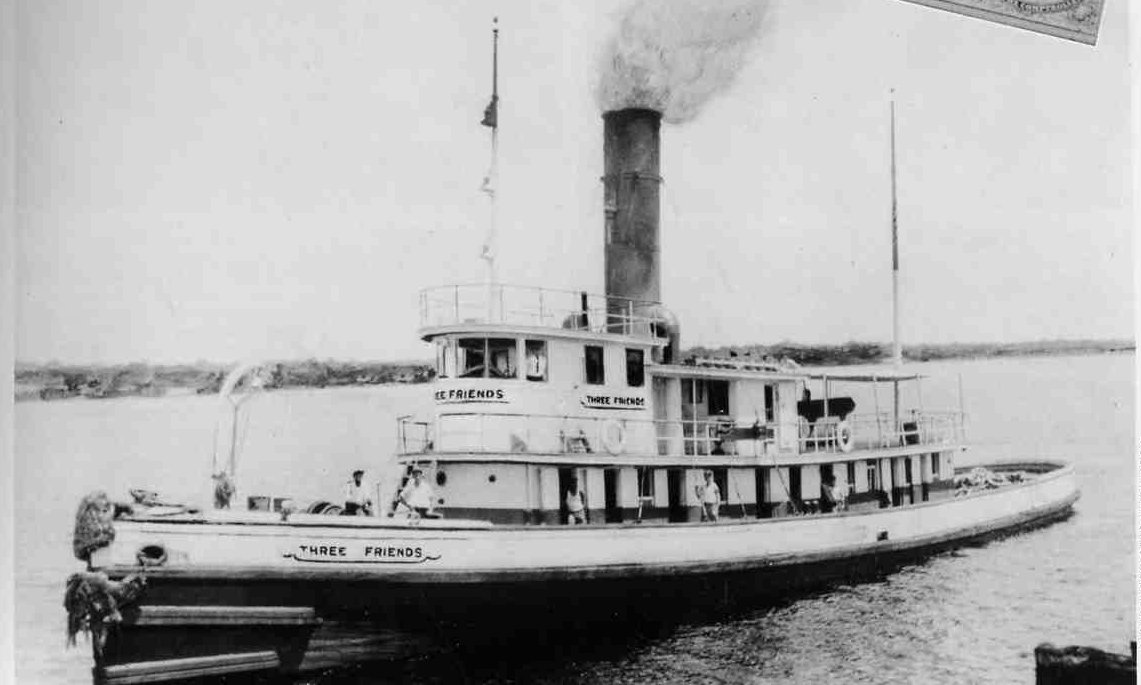

Broward, his brother Montcalm, and George DeCottes started building The Three

Friends. Almost as soon as it was completed, Broward used it in 1896 to carry arms and munitions from Nassau to Cuban

independence revolutionaries on the island. Broward piloted the seagoing tug

to Cuba, carrying a Cuban hero, General Enrique Collazo (veteran of the Ten

Years' War), two officers, fifty-four men plus arms and ammunition to Cuba,

giving the insurrectionists much-needed hope. Jacksonville Cubans had made the

arrangements; their countrymen had begun fighting in 1895 to overthrow the

Spanish colonial regime and would continue to do so even after the United States

joined the fray on April 11, 1898; Americans refer to it as the Spanish-American

War. Running guns was a profitable and exciting business. and he made eight illegal trips. Broward was so

good at it that Spain complained but U. S. authorities could not catch him. The

most the United States government did was impound his boat several times. People in the

United States, including U.S. government officials, supported the liberals who

were trying to achieve Cuban independence from the conservative

Spanish monarchy, the last vestiges of the Spanish Empire created in the 16th

century. Thus, although Broward was a criminal, many considered him a daring

hero. U.S. involvement in the Cuban war for independence meant all charges

were dropped.

Three Friends

His fame as a gun runner against an unpopular government fostered his

political career as did the money he earned from transporting arms, munitions,

and rebels. The Straighouts

tried to get him to run for sheriff office in 1896 but he was too busy making

money. The end

of the war in 1898 ended this business but his reputation for prowess as a ship

captain brought him plenty of other business. In 1900, he agreed to run for the state House of Representatives and won a

resounding victory. He supported liberal measures including a political primary

system to replace the state convention system which the conservatives

controlled. He fought to establish a railroad commission to insure that

these corporations served the public interest. Hamilton Disston of Phliadelphia and

others paid $1 million for 4 million

acres of public land or 25 cents an acre. The land was sold by the Internal Improvement Board and the

Governor to pay the debts of the Board. This sale angered many people who saw it

as a give away to the rich. Big corporate interests were seen as villains

by small farmers the bulk of the population. The railroad barons such as

Henry B. Plant and Henry M. Flagler were awarded vast tracks of public land.

Railroads controlled much of Florida, charging whatever rates they chose.

Liberals held attitudes similar to the Populists, measures they thought would

help the common man instead of the privileged few.

Yet, he cooperated with conservatives' and Flagler's assault on traditional marriage.

Even though conservatives, led by Flagler, were "political enemies" and even though the vast majority of Floridians

believed in the sanctity of marriage, Broward voted with them on this issue.

Christianity historically forbade

divorce except in extreme circumstance, abiding by the commandment "what

God has joined together, let no man put asunder." One married "for

better or for worse." If one's spouse became ill, it was a divine duty to

take care of the spouse. Flagler, however, wanted to ditch his mentally ill second

wife, Ida Alice Shourds. She had been hospitalized for mental illness for six years.

The younger Mary Lily Kenan had caught his fancy. Florida law would not let him.

Flagler, of course, was one of the richest, most powerful, richest men in

the state; he

got the law changed in 1901. Broward voted for the "Flagler

Law." So Broward voted for it even though Flagler, the Standard Oil and railroad baron,

controlled much of the state and the the conservative faction in state politics.

Floridians protested, for it was a radical departure from traditional marriage. Perhaps Broward agreed; perhaps he understood that the

bill was unstoppable. Perhaps both. On August 24th of that year, Flagler

married Kenan; he wasted little time.

Broward's first stint in state government was successful, for he remained

powerful and popular but he also had family obligations. He

did not run again for the state House in 1902. He also served from 1901 to 1904 on the

State Board of Health. Instead, he concentrated on his

lucrative salvage business, especially in the Key West area. He had a wife and

six daughters to support. Although he had successful business interests in the

Jacksonville area, the lure of the sea and big money were irresistible. At

least, for a time.

Supporters begged him to run for governor for the 1904-1908 term,

arguing that he was the only liberal who could win. Duncan U. Fletcher, a fellow

liberal politician, had a strong political base in Jacksonville where he was

mayor, but not the statewide fame of Broward. In 1903, Broward agreed to run.

The road to Tallahassee was going to be tough because the newspapers were

largely owned by railroads and other corporations. The state's elites, living in

cities, would finance his opponent. Broward's gubernatorial campaign was a run against the urban rich and the

railroad interests. His chief opponent, Robert W. Davis, was Flagler's man; his

record in Congress was ample proof. Broward campaigned in the rural areas

where the majority of the population lived. He stressed that he had always

sought what was best for the majority sand would continue to do so. And he

traveled throughout the state, meeting and speaking to people. He advocated draining the Everglades

to create rich farm land to benefit the average Floridian. The race went into a second primary, he won by 400 out of 45,000 votes.

Democrats automatically won the the general election in November. He became governor

on January 3, 1905.

As governor, he was an activist. His program of draining parts of the Everglades

gave him national

prominence. Although 21st century people would question changing the environment

so drastically, Broward and those who supported the project believed they were

helping the common man by providing cheap farm land. He reorganized the higher education system so that there were only

three colleges—Florida (for men), Florida A & M, (for African Americans) and Florida State College for Women.

The University of Florida moved from Lake City to Gainesville, a sign that the

state's population was shifting southward. He supported a state

textbook commission, free school books, a permanent Railroad Commission, and hospital reforms. He failed to get a law creating life

insurance for Floridians and a state insurance commission.

Surprise twists of fate encouraged him to seek the U. S.

Senate. On December 23, 1907, U. S. Senator Stephen Mallory died suddenly. On

December 26th,Broward appointed his gubernatorial campaign manager, William James

Bryan, to replace him. Bryan was only 31 years old and there was an uproar

that a callow youth received this plum position. That ended when Bryan died

of typhoid fever n March 22, 1908! Broward decided he would run so he then appointed William Milton on the

condition he would not run in the next election. Broward ran against the

conservative John Beard and the moderate liberal Duncan U. Fletcher, mayor of

Jacksonville. He and Fletcher went into the second primary but Fletcher won.

Broward lobbied to be the Vice Presidential

candidate under William Jennings Bryan, the popular, perennial Democratic candidate.

He came close to being chosen. It was not to be. After

all, Florida was a small frontier state. Bryan needed someone who could attract

more votes so he chose John Kern of Indiana.

Broward refused to give us his ambition to play a role on

the national stage. He ran for the U.S. Senate against the incumbent, James

Taliaferro. in 1910. He won. His victory in the general elections in

November was a foregone conclusion.

Exhausted by campaigning, he vacationed

at Fort George island on the north shore of his beloved St. Johns River. He died

there in late September of gallstones. He was buried on October 4th. He was only

fifty-seven. The Broward Era did not quite end with his death, however. Nathan

Bryan, brother of William James Bryan was elected and served only one term.

Senator Fletcher, who served until his own death in 1936, was a moderate liberal

politician who brought lots of federal money to Florida during the New

Deal.

__________________________________________________

Samuel Proctor, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward: Florida's Fight Democrat.

Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 1993.

Flynt, Wayne, Duncan Upshaw

Fletcher, Dixie’s Reluctant Progressive. Tallahassee: Florida State

University Press, 1971.

BiographyBase, "Napoleon Bonaparte Broward

Biography."

"Capt. Liscomb Returns," New York Times, May 9, 1897 tells the

story of a Harlem man, Captain Alfred Libscomb, who also ran guns and people to

Cuba during its independence revolution and had to evade the Vesuvius.

Susan D. Brandenburg, "Lynching That Didn't

Happen," May, 2006. Review of Margaret Vandiver, Lethal Punishment (Rutgers

University Press, 2006).

Gustavo J. Godoy, "Jose Alejandro Huau: A Cuban Patriot in Jacksonville

Politics," The Florida Historical Quarterly, October 1975, volume 54 issue 2, pp.196-206.

" Collazo Safely Landed ," New York Times, March

19, 1896.

"Shot Down By Soldiers," New York Times, July 7,

1892.

“Corbett in Active Training,” New York

Times, December 25, 1893.

“May Declare The Fight Off,” New York

Times, January 20, 1894.

“The Fight Still In Doubt,” New York

Times, January 25, 1894.

“The Vanity Of A New York Woman Wintering in

Florida Got Her In Trouble,” New York Times, January 28, 1894.

New York Times, November 30, 1897.

John W. Cowart, “Gentleman Jim Corbett’s Big

Fight,” 2005.

Foley, Bill. “Jacksonville's boxing title

match had real sideshow,” Florida Times-Union,

February 23, 2000.