I. Introduction

Powerful

men in Jacksonville (I have named them Beach Railroad Men) founded and operated

short line railroads from the east side of the St Johns River either from South

Jacksonville or Arlington to the ocean shore in the 1880s and 1890s. They hoped to earn a profit from the

Jacksonville & Atlantic (which connected South Jacksonville to their settlement of Pablo Beach) and the

Jacksonville, Mayport, and Pablo (which connected Arlington to the Atlantic

Ocean at the short-lived Burnside Beach). They also wanted to get to the shore

easily to escape the city's heat in the summer. Neither railroad survived per

se. It was only the multi-millionaire Henry M. Flagler who managed to

reorganize and operate one for several decades before it also disappeared. This essay is a look at the men behind the

railroads not of the railroads themselves although the study contains most of

what we actually know of the roads themselves.

Florida was

fertile ground for ambitious men. It had almost no railroads in 1880;

Jacksonville, its boom town, had only one in spite of it being the city though

which most goods and passengers passed. Railroads could move people and goods

fast and cheaply so many were bring built though out the country. Jacksonville

was no exception for it was the essential entrepôt for people and goods

entering Florida. New money exploited the possibilities and opportunities

presented by Jacksonville. Timbering,

naval stores, and real estate development were creating fortunes for ambitious

and daring men. The governments of the United States and of Florida gave public

land to corporations to build railroads for they were land rich and capital

poor. Such public-private partnerships were common in U.S. history. That some

men got rich was just an incentive.

Most of the railroads from Jacksonville went west and south.

Jacksonville

in 1880 was primitive by today's standards. The city government performed the

common municipal services such as police and fire protection and garbage

disposal. The unpaved streets were cleaned but not swept. The sidewalks in the

business district were made of wood with a few paved with stone. There was no

public transportation nor sewer system.

Waste disposal included chamber pots, privy-vaults, privies, boxes,

barrels, and much burning of whichever waste could be incinerated. Ashes would

be used for fertilizer. Infectious diseases were always a threat, particularly

yellow fever. People with smallpox were

segregated from the general population

for the duration of the disease but not those with scarlet fever. Vaccination was voluntary. The city

authorities had the power to close schools in case of an epidemic. The city owned the water works but the gas

works were private and the city government paid $2,212 a year for the gas for

its street lights. The city leased the grounds for the municipal market of

about 100 square feet and tried to insure sanitary conditions since this was

the primary source of meat and vegetables. Only one public park, an acre in

size, existed. Jacksonville lay entirely on the west side of the St Johns River

in a very small area. It grew by annexation and well as by immigration.[1]

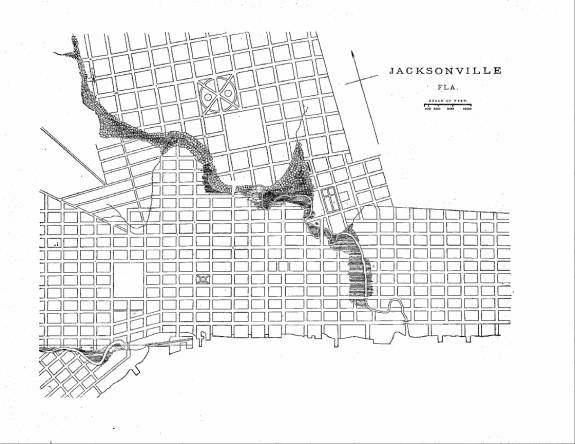

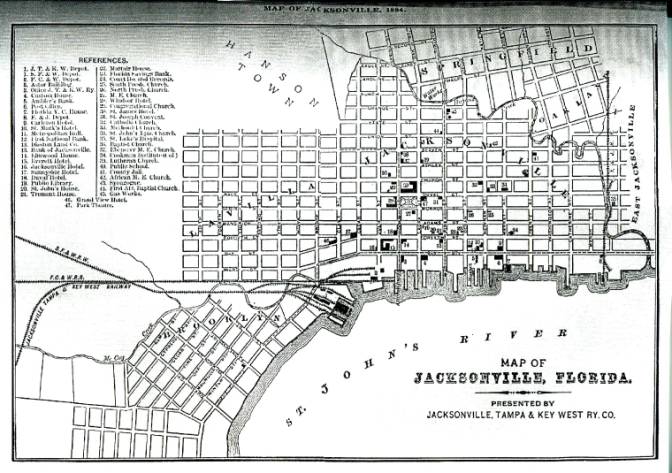

The two maps below show Jacksonville itself in 1880 and Jacksonville with its suburbs

in 1884.

Jacksonville, 1880 with the river at the bottom

Map of Jacksonville, 1884, Presented by

Jacksonville, Tampa & Key West Railway Company

|

J.T. & K. W. Depot; S. F. & W. Depot

|

25

|

South Presbyterian Church

|

|

F. C. & W. Depot

|

26

|

North Presbyterian Church

|

|

Astor Building; Office of the J.T. & K. W. Ry.

|

27

|

M. E. Church

|

|

Custom House

|

28

|

Windsor Hotel

|

|

Ambler's Bank

|

29

|

Congregational Church

|

|

Post Office

|

30

|

St. James Hotel

|

|

Florida Y. C. House

|

31

|

St. Joseph Convent

|

|

F & J Depot

|

32

|

Catholic Church

|

|

Carleton Hotel

|

33

|

Methodist Church

|

|

St. Mark's Hotel

|

34

|

St. John's Episcopal Church

|

|

Metropolitan Hall

|

35

|

St. Luke's Hospital

|

|

First National Bank

|

36

|

Baptist Church

|

|

Disston Land Co.; Bank of Jacksonville

|

37

|

Ebenezer M. E. Church

|

|

Elmwood House

|

38

|

Cookmen Institute (Colored)

|

|

Everett Hotel

|

39

|

Lutheran Church

|

|

Jacksonville Hotel

|

40

|

Public School

|

|

Sunnyside Hotel

|

41

|

County Jail

|

|

Duval Hotel

|

42

|

African M. E. Church

|

|

Public Library

|

43

|

Synagogue

|

|

St. John's House

|

44

|

First African Baptist Church

|

|

Tremont House

|

45

|

Gas Works

|

|

Mattair House

|

46

|

Grand View Hotel

|

|

Florida Savings Bank

|

47

|

Park Theatre

|

|

Court House and Records

|

|

|

Most of the

men in this study lived in LaVilla, East Jacksonville, and Springfield but most

lived within Jacksonville itself. Although difficult to see on this scale,

office buildings, churches, docks, and Hemming Park are shown on this map.

Their banks existed within a few blocks of each other as the map shows:

Ambler's Bank (5), First National Bank (12), Bank of Jacksonville (13), Disston

Land Company (13) which was in the same building as the Bank of Jacksonville,

and the Florida Saving Bank (23). Brooklyn, to the south of LaVilla, ceased

being land after the Civil War to be developed into a residential neighborhood;

its southern portion was sold and became Riverside. Brooklyn was annexed by

Jacksonville in 1887. Oakland was

primarily an African American community. Hanson Town was a primarily

agricultural area which was an African American community.

My approach

is to include brief biographical snippets and photographs of the officers and

major stockholders of the two Jacksonville-owned railroads, when possible. In

other words, my interest is who was working on the railroad at the highest

levels, who had the audacity to invest capital in such enterprises. The research involved a vast array of sources

as indicated by the bibliography. Too often, I was unable to find biographical

material of an images other than en entry in a city directory. Henry M. Flagler

is the subject of many studies; he is included here because he bought and

converted the Jacksonville & Atlantic.

The

men in this study sought escape from

the summer heat by retreating to the beach and its breezes as well as the hope

of earning even more money. In the

spirit of the times, railroads seemed the solution to crossing the broad St

Johns River to South Jacksonville and then to travel across scrub land,

marshes, and creeks to reach the beach. There were sand or dirt roads or trails

but travel on them was arduous A railroad would add value to beach land was

virtually worthless until a reliable means of getting there was found, one that

would allow one to cross creeks, marshes, a small river, and scrub easily.

Legally,

these men were involved in one or more of four railroad corporations—the

Arlington and Atlantic Railway Company (1882), the Jacksonville and Atlantic

Railroad Company (1882-1893), the

Jacksonville, Mayport, and Pablo Railway and Navigation Company (1886-1895) and

the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railway (1893-1899—but then there were only two

because some were the same road but under different names. The JM&P and the

others; the ownership and management changed according to the vicissitudes of

the time. This essay focuses on the men who were directors of the various

companies before Henry M. Flagler bought the narrow gauge Jacksonville and

Atlantic to reach a river port where coal for his engines was offloaded. His

Beach/Mayport Branch of the Florida East Coast Railway (1899-1932) is briefly

considered since it closed the railroad era of the Jacksonville Beaches. A chapter is devoted to each railroad with

the one on the Florida East Coast Railway

branch to the beach and Mayport to show what professional railroad men encountered.

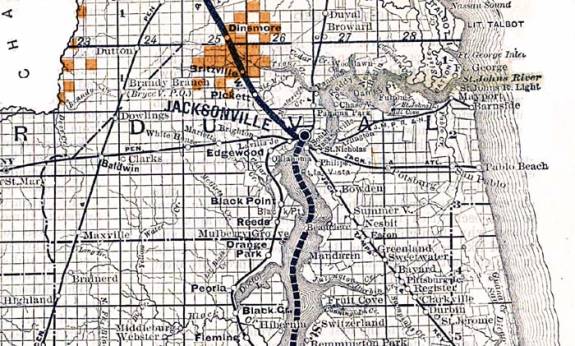

1888 Map of Duval County, FL showing the two beach railroads