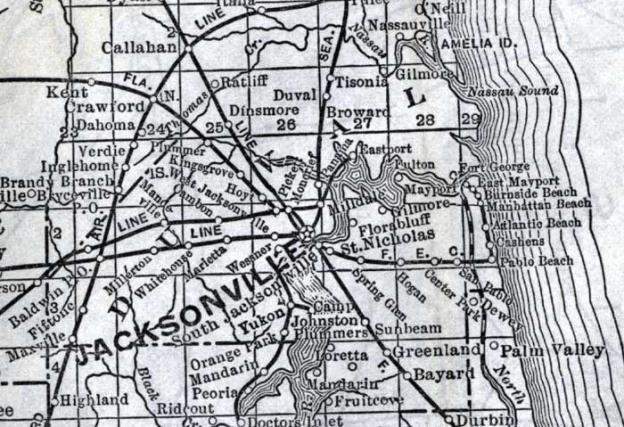

II. Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad

The first

name of the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad

was the Arlington and Atlantic Railway Company incorporated on August

29, 1882 to run from Arlington (see map) to the beach by John Q. Burbridge,

George B. Griffin, and Jonathan C. Greeley. It is not clear whether Griffin or

Burbridge was the initiator. All three men were engaged in the real estate

development and the coastal area was a potential development. Jack Pate, a

retired U.S. Navy Captain who wrote articles on beaches history, asserts that

Griffin conveyed some of the original beach property to the railroad company,

receiving two lots in exchange.[1]

Burbridge is credited by other sources as the one who acquired free land from

the State of Florida. Florida had little money but lots of land so it offered

acres of land free for every mile or railroad built, a practice the United

States government had been utilizing to subsidize the building of

transcontinental railroads. Perhaps the

purpose of creating this corporation was to acquire free land from the citizens

of Florida because the corporation became the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railway

Company on September 28, 1882.

Griffin, Greeley, and Burbridge were powerful men in

Jacksonville but only Burbridge was devoted to the project. Their individual

biographies shed some light on why each involved himself in railroading to the

beach. Griffin and Greeley dropped out.

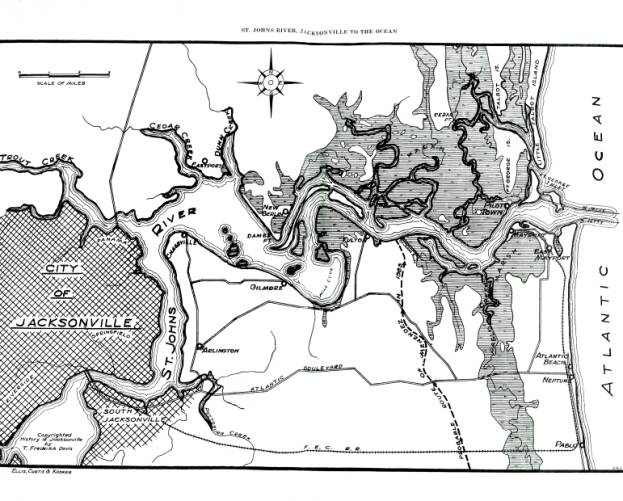

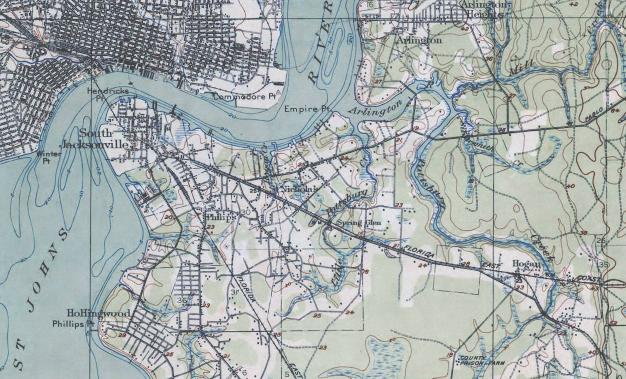

Jacksonville and

eastern Duval County, 1925

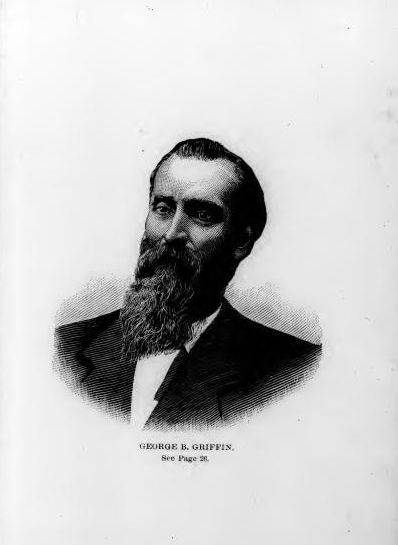

Charles B. Griffin

Griffin

was a native of Jefferson County, New York (the county seat is Watertown) on

Lake Ontario. He was born April 4th,

1819 on this cold border with Canada.

At age twenty-one in 1840, he went to sea on a fishing boat bound for

the fishing grounds of Newfoundland. His physician thought the bracing,

strenuous life would improve his health. The enterprising young man was the

cook who learned on the job. The captain and crew must have forgiven him often

during the voyage. The voyage did toughen him as well as convincing him that

staying on land was more enjoyable. In my estimation, worked a season or two

fishing and then headed to Chicago, a city charted in 1837, and helped build

the City Hotel at the southeast corner

of State Street and Lake Avenue. Then he went to Madison, Wisconsin

where he engaged in business[2]

and became a prosperous merchant.

He returned

to Chicago eventually because its city directory of 1871 shows him in a real

estate partnership with a fellow named A. G. Storey. He lived at 567 Washington

Avenue with one male and five females.

The Great Chicago Fire of October, 1871 destroyed the downtown business

district and many residential areas. The Panic of 1873[3] was

harder on his finances than the fire for it was more sweeping. It wiped out

most of his assets while making it difficult to sell real estate. In 1875, he

was in business by himself with an office in 9 Major Block and a residence on

646 West Adams. At age 54 or later, he

decided to take what he had left and move to sunny Jacksonville, Florida where

opportunity abounded.

In

Jacksonville, he was involved in

developing two street railways, the creation of Evergreen Cemetery, the

platting of Springfield, Campbell's Addition and Burbridge's Addition, the

development of Pablo Beach, and the

Arlington and Atlantic Railway which became the Jacksonville and Atlantic

Railway. According to C. A. Rohrabacher[4], “he

conceived the idea of the Pablo Beach railroad and seaside resort, in which

enterprise he acted in unison with Mr. Burbridge, who put much of his time and

many thousands of dollars into the company.”

By 1887, Griffin and his son were engaged as real estate,

loan and investing agents (G.

B. Griffin & Son) but Griffin

left most of his Jacksonville affairs to run by his son F. B. He moved to the

town of Windsor in Alachua County focused his attention on Windsor, Inverness in Hernando County, and central

Florida real estate interests.[5]

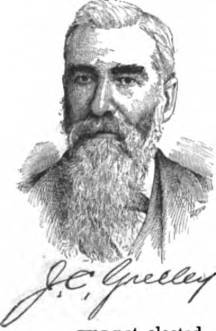

J. C. Greeley

Jonathan Clark Greeley was another Yankee who migrated to

Florida but long before Griffin and Burbridge. His father had moved from New

Hampshire to Maine. He was born on his parents’ farm in Palermo, Waldo County,

Maine on July 6, 1833. The Sheepscot Valley is almost 1,400 miles from

Jacksonville. Of course he worked on the farm; there was little other

employment. He went to the local common school in the winter for his early

education. Maine, once part of Puritan Massachusetts, required that children be

taught reading, writing, and arithmetic but it was a poor state with its people

scattered in small pockets. Even in the 21st century, Palermo only

has 1,200 people. Free public/government high schools did not exist until the

1890s. Young Jonathan, like most who wanted further education, had to work

during vacations to earn the funds to pay his fees at Lincoln Academy in New

Castle Academy. He then became a teacher, earning enough to pay off the family

mortgage.

People

“Down East” tend to be very hearty but suffered severe lung problems

exacerbated by the Maine cold. Somehow, the nineteen year old made his way to

Palatka, Florida in 1852, passing through Jacksonville as he did so. In all

likelihood, he made his way by ocean to Jacksonville and by river steamer up

the St. Johns River. It was a wise move in several respects. He recovered his

health. He became so popular in the village that he was elected an alderman at

age 22.

He married Lydia Forward of Palatka in 1858. but she and

their eight and one-half year old son were lost at sea on October 23,

1865. He then married Leonora Keep in

1867; she died in 1886. The three children of this marriage were “Allan, who

has just graduated from the University of Michigan, at Ann Arbor; he was

previously graduated from Yale; Florence, now Mrs. Dr. James G. DeVeaux, of New

York, and Mellen, aged fourteen, at school in Lawrenceville, New Jersey.” [6]

He was

always loyal to the United States which paid off. He refused a Confederate Army

commission in 1861 but served, reluctantly, in a state militia. He was elected

to the state House of Representatives 1862-63. He escaped certain conscription

into the Confederate army in January 1864 by running the blockade at sea and

reaching Maine in March, 1864 he returned to Maine. When the war ended, he

moved to Jacksonville and became a merchant. Under the Reconstruction

government, he was rewarded for his loyalty to the US by being appointed deputy

collector of internal revenue and assistant assessor for Duval County in

1866. He held the job for seven years.

In 1866 as well, part of Unionist group

that took control of the Florida Times newspaper.

In 1868, the Governor Harrison Reed appointed him county treasurer and the next

governor, Ossian Hart, reappointed him

in 1873. He held that office for seven years. He served as an alderman and then

as Mayor of Jacksonville for the 1873-74 term, all under the Republican control

of Florida. The Duval County Circuit court appointed him the receiver for the

Jacksonville, Pensacola and Mobile Railroad in 1874 but ownership of the road

was disputed for five years.

Reconstruction

ended in Florida with the Compromise of 1877 bringing white conservative

Democrats back to power; Republicans such as Greeley no longer fared well in

politics. He ran for ran for Lieutenant Governor as an independent in 1882 and

lost. He did win election as a State Senator in 1883 and served through 1886.

During that term he made an unsuccessful run for a seat in the U. S. House of

Representatives in 1884. He was elected by fellow Republicans to the party’s

state convention in 1885 but the party was in sharp decline in conservative

Florida.

His

political sentiments did not prevent him from becoming a major economic force

in Jacksonville and elsewhere in Florida. In 1874, he founded the Florida Savings Bank and Real Estate

Exchange, a bank which lasted until 1888 when depositors withdrew $100,000 and

fled the city during the great yellow fever epidemic of that year. He invested in real estate throughout his

business career and was one of the founders of The Springfield Company in May,

1882 which developed the suburb of Springfield adjacent to the northern

boundary of Jacksonville and built a streetcar line (Suburban Railway and Land

Company) to connect the two. In 1882,

as we know, he was an investor and director of the Arlington and Atlantic

Railway Company. In August, 1884, he would be a Director of the Gulf Steamboat

Company of Cedar Key. In spite of the yellow fever epidemic in 1888, the Land

Mortgage Bank, of London, England, was organized in Jacksonville, with the firm

of Greeley, Rollins & Morgan as resident agents to loan money on Florida

land. It loaned over two million dollars on real estate, purchased 75,000 acres

mostly for phosphate mining, and erected a $75,000 phosphate mine. By

1895, he was President of the Florida Finance Company, with a capital of

$250,000 and President of the Indian River Pineapple and Cocoanut Grove

Association.[7]

The

proposed little railroad held scant interest compared to his other activities.

It was Jack Burbridge who carried the project forward.

The directors petitioned the Secretary of State to change

the name to the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad Company with Burbridge,

James M. Schumacher (sometimes spelled Schumaker), and William M. Ledwith as

the incorporators.[8]

They decided to build from South Jacksonville to the coast, using a ferry to

cross from Jacksonville. Francis Spinner was not one of the three men who

incorporated the J & A but he and Schumaker were such a team that their

biographies are placed together.

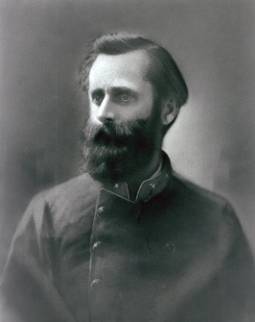

John “Jack” Quincy Burbridge

John “Jack” Quincy Burbridge was born in Pike County

Missouri in May 21, 1830 and lived in Louisiana, Pike County, Missouri (90

miles north of St. Louis)before the Civil War. He was educated at St Louis

University, a Jesuit school. He joined the California Gold Rush in 1849 and

returned to Missouri three years later in 1852. By 1860, his general

merchandise business was successful. He was also a banker in Louisiana,

Missouri and, perhaps, city treasurer.

Missouri was a state, admitted as such by the Missouri

Compromise of 1820 but less than ten percent (10%) of the population was

enslaved by 1860. Nevertheless, there was strong pro-slavery sentiment in the

state. Pro-slavery Missourians had crossed the border to fight in the civil war

in the Kansas Territory. On the eastern side of Missouri along the Mississippi

River slavery was more prevalent. When the Civil War started, Burbridge threw

his lot in with the Confederates even though Missouri stayed within the United

States.

The pro-Confederate Governor O. F. Jackson appointed him as

a Captain of Company B of the 1st Infantry, 3rd Division of the Missouri State

Guard; he rose to Colonel. He later became Colonel in the 2nd Cavalry, 2nd

Division Missouri State Guard, then Colonel of the 2nd Missouri Infantry (Confederate States of

America), and lastly Colonel in the 4th Missouri Cavalry (CSA),which was also

known as Burbridge's Cavalry. Captain Burbridge was captured and held in the

Camp Jackson Affair just outside of St Louis in May, 1861 but then

exchanged. The bloody Camp Jackson

affair[9],

polarized the state into pro- and anti- slavery factions or pro-US and

pro-Confederate factions. He was elected Colonel of the First Missouri regiment

of infantry on July 2, 1861. A few months later, he was shot in the head the

Battle of Wilson's Creek (Oak Hills)[10] near

Springfield, Missouri) on August 10, 1861. He and his troops surrendered at

Shreveport, Louisiana in June, 1865 and he took his men back to St Louis and

disbanded his unit. After the war he

had businesses briefly in St. Louis, Missouri and Alton, Illinois where he met

and married Maltida Gutzweiller. The 1880 U.S. Census shows him with five

children as a flour manufacturer.[11]

By February, 1882, he was living in Jacksonville on Laura

Street at the corner of Adams and owned the Palmetto Brush Company. We don’t

know when and why he moved some nine hundred miles to frontier town of

Jacksonville, Florida from St Louis. Jacksonville and its suburbs contained

15,904 according to the estimate of Webb’s City Directory (1882). It was a town

connected to the interior of the state by the navigable St. Johns River and to

the east coast of the United States by the Atlantic Ocean into which the St.

Johns emptied.[12]

He was involved in real estate in the suburbs of Jacksonville and in

Gainesville. His Burbridge's Addition was northwest of present downtown

Jacksonville almost adjoining the suburb of Springfield.

He became friends with Griffin and “conceived the idea of

the Pablo Beach development, and in 1883 procured for that purpose about 700

acres of beach land from the government and the Disston Land Company.”[13]

The directors’ meetings of the Jacksonville and Atlantic would be held in his

office. More on this later. He would be President from 1884 to 1886.

In 1887, the Jacksonville city directory listed the

Burbridge Company, grocers, at Ocean near Forsyth with offices at 17 West

Forsyth. He seems to have left the real estate business. John Q. Burbridge

lived at 87 E. Monroe. He was also a founding member of the Board of Trade

[Chamber of Commerce] in 1884 and mayor of Jacksonville in 1887. He was

instrumental in maintaining the public library. He developed throat disease,

probably cancer, and moved to Arizona where he died in 1892.

He

assembled a sterling group of directors for the Jacksonville and Atlantic.

Their biographies demonstrate this.

General

William M. Ledwith fought as a colonel on the staff of Robert E. Lee and surrendered

him at Appomattox in April, 1865. His rank as general came from his service in

the Florida State Troops. Ledwith was born in Micanopy, Florida on September

12, 1832. From this Alachua County village he moved to Jacksonville where he

stayed until 1848 when he left for Essex, Connecticut to prepare for

college. He graduated from Brown University in 1854 where he was a member

of Phi Beta Kappa and Theta Delta Chi social fraternity. After graduation, he

taught languages for a year in Providence, Rhode Island and then went to Europe

for two years, teaching English literature and mathematics while he read law

for the bar exam. His father was Collector of Customs. When the Civil War began

in 1861, he joined the Confederate army. After the war, in 1866, he married a

woman from Lake City and became a father. By 1870, he was a deputy sheriff

living with his wife and four year old son in a $25,000 house. He was a lawyer and a member from

Jacksonville of the Florida House of Representatives in 1879. He served as a

city councilman. President Chester A. Arthur appointed him postmaster. Governor Francis Fleming appointed him as

Superintendent of Public Instruction, As with many of the other railroad

directors, he was involved in real estate development in the Jacksonville area

and elsewhere in the state. By 1887, he was the proprietor of Haines City on

the South Florida Railway about 50 miles south of Sanford. In 1888, he was an

at-large delegate to the Republican National Convention and still lived in

Jacksonville. He died in 1901[14]

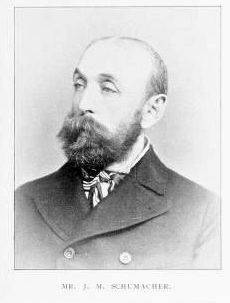

James M. Schumacher

James M. Schumacher, President of the railroad 1886-1890,

was a man with clout. Schumacher was born in Mohawk, Herkimer County, New York,

on November 18th, 1843, son of a wealthy leather manufacturer,. He graduated from

Tufts College [now University] in 1863, studied law at Michigan and then

apprenticed in a law office at home and was admitted to the New York Bar. He

married Josephine Caroline Spinner, youngest daughter of General Francis E.

Spinner, on November 6th, 1871, at Mohawk, New York. He moved to Jacksonville

in 1874 at the instigation of his father-in-law, a former Treasurer of the

United States and they organized the First National Bank of Florida.

Stockholders included the Remington arms people also from Herkimer County, New

York and Colonel T. W. C. Moore, a prominent art collector who had served on U.

S. General Phillip Sheridan’s staff in the Civil War. He became a member of the Bar of Florida and was granted the

right to practice law in the United States courts.[15] He

was a founding member of the Board of Trade. He was Treasurer of the J & A

under Burbridge’s presidency. He served in the state Senate 1888-90. He was

Commissioner of Public Works (1890-93). He was a director of the Florida

Central and Peninsular Railway Company for two years. He was also vice

president of The Springfield Company and the Main Street Electric Railway.

Schumacher and his bank became involved in phosphate business.

Francis E. Spinner

General Francis E. Spinner was an important person even

after his service to the United State government. He was born on January 21,

1802 in Herkimer County, NY. He rose to the position of Major General in the

state militia, became county sheriff; and became president of Mohawk Bank; and

a state official. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives 1855-6,

President Abraham Lincoln appointed him as Treasurer of the United States in

which post he served from March 16, 1861 until his resignation at age 73 on

July 1, 1875. He moved to Jacksonville and then to Pablo Beach until his death

on December 31, 1890. He was an unconventional man in many ways. As Treasurer,

he had advocated and achieved the employment of women in the Department. In

retirement, he lived in his tent city, Camp Josephine, on the beach! [16]

Spinner and family in front of Camp Josephine, Pablo Beach

Eventually the directors would include John Q. Burbridge, J.

J. Daniel, James M. Schumacher, H. S. Ely, Francis F. L'Engle, Samuel B. Hubbard, Mellen W. Drew, Patrick McQuaid, W.

T. Forbes and W. A. MacDuff (often spelled McDuff). Each made his mark on

Jacksonville.

Colonel J. J. Daniel

Colonel J. J. Daniel

Like

Burbridge, James Jaquelin Daniel (known as J. J.) had been a Confederate

Colonel in the Civil War, fighting 1st Florida Infantry Reserves in 1864-65. He

was born in Columbia, South Carolina in 1830; and moved to Jacksonville as a

child; and eventually became a lawyer. When the Civil War began, he raised the

First Company of the Second Florida Infantry, ''the St. Johns Grays,'' to fight

on the Confederate side. He was

commander of the forces at the Battle of Natural Bridge (March 6, 1865) until

injured. After the war, he returned to Jacksonville and entered the lumber

business and resumed his law practice. He was a partner in the law firm of

[Colonel Lewis I.] Fleming and Daniel. Francis Fleming, one of his law

partners, was elected Governor in 1889. Daniel was active in civic affairs,

including the creation of Evergreen Cemetery. In late December, 1885, Col. J.

J. Daniel, president of the company, resigned effective January 5 [1886] to

accept position as commissioner to investigate the work of the Okeechobee

Drainage Company. He was president of the Times-Union

and the Florida Publishing Company. In

1887, he was President of the Board of Trade and Vice President of the National

Bank of the State of Florida. He lost his life October 2, 1888 from yellow

fever as he assisted other stricken during the great epidemic of that year.

Henry S. Ely, treasurer of the Jacksonville and Atlantic

Railroad in 1882 was also affiliated with the Florida Savings Bank. In 1884, he

was a Director of the small railroad the Gulf Steamboat Company of Cedar Key

along with Greeley and Schumacher. In 1886, he was a Director of the St.

Augustine and Pablo Beach Railroad Company along with J. M. Barrs, S. B.

Hubbard, Patrick McQuaid, and others. He was Secretary and Manager, The

Springfield Company located in Ely’s Block. He contracted yellow fever early in

September, 1888 and survived unlike Daniel.

Francis Fatio L'Engle, born in Florida in 1830 of a Florida

mother and a father from the Dominican Republic and was a prominent lawyer and real estate

developer. He was a Confederate Army

Lieutenant in Florida during the Civil War. After 1865, he purchased land west

of Jacksonville, subdivided it, and named it the Town of La Villa. The town had whites in its easternmost

section, adjoining Jacksonville, but was majority black, as was Jacksonville.[17]

In 1880, he lived in La Villa with his wife Charlotte, two sons, two daughters,

and a twenty-seven year old African American male servant. His older son,

Porcher, was Mayor of La Villa and would purchase one of the first lots at

Pablo Beach. In 1887, Francis and Porcher shared law offices in Ely’s Block.

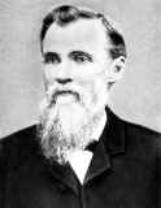

Samuel

B.Hubbard

Samuel

B.Hubbard

S. B. Hubbard [Samuel Birdsey Hubbard][18]

saw the light of day first on June 18, 1833

in Wadesboro, North Carolina, where his father was a very successful

merchant for thirty years until he decided to return to Connecticut in 1837 and

became a farmer. Young Samuel worked on the farm and went to school in the

winter when the ground was dormant.

After elementary school, he attended Chase Academy in Middletown for

four years, a very high level of education. He returned to North Carolina to

work in a general merchandise store and then, in 1853, to a family store in

Pine Bluff Arkansas as a partner. He endured illness to the point that he left

in 1860 and returned to Connecticut. Someone mentioned that he go to

Jacksonville for health. He had money so he took the train to Jacksonville and

arrived in 1867. Immediately, his health improved.

Hubbard was a highly educated,

experienced businessman with money. He saw the need for a well-organized

general store, he opened the S.B. Hubbard Company, the first wholesale hardware

store in Florida. Although the building burned three times before 1895, he

rebuilt and prospered. By 1891, S.B. was a force to be reckoned with. He

expanded into the banking business and opened the Southern Savings and Trust

Company. As its President, he quickly built its capital base to over $150,000.

He owned or was a partner in the Citizens’ Gas Company, the Jacksonville

Electric Company, the Jacksonville Electric Car Line and the Springfield Land

Company. In 1878, the mayor appointed

him to oversee the city improvements. He served as a city councilman but

politics was not his métier. Hubbard concentrated on his business interests. He

died at the age of 70 in 1903.

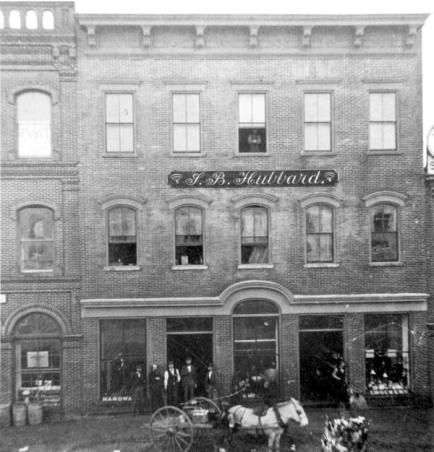

S. B. Hubbard Company, Florida’s first wholesale hardware

business.

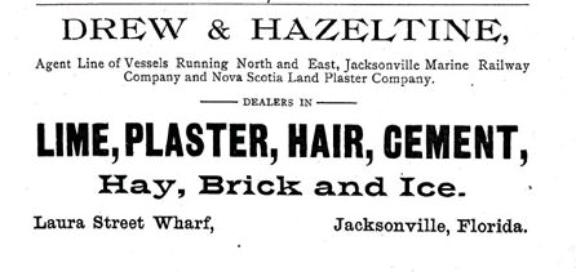

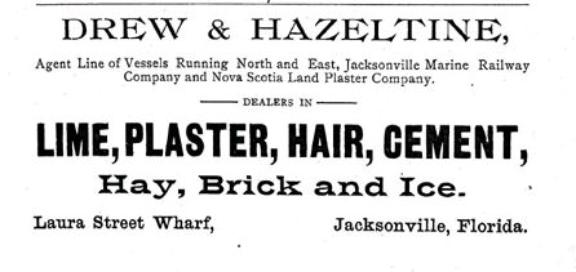

Mellen W. Drew of

Drew, Hazeltine &

Livingston, a company which sold building materials, hay, ice, and supplies to dockyards was involved in the Jacksonville

and Sterling Railroad. He was Director of the Jacksonville Cemetery

Association. He became President of the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railway

Company in 1890.

Drew & Hazeltine Advertisement

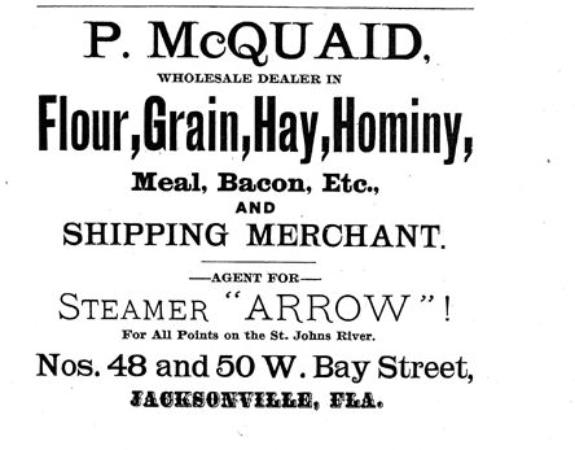

Patrick McQuaid, an Irishman who arrived in Jacksonville in

1867 from South Carolina died at the young age of 43 in 1892. He was twice

mayor of Jacksonville (1886-87, 1888-91). In 1886, he became a director of the

St. Augustine and Pablo Beach Railroad Company along with Hubbard, John E.

Hart, J.M. Barrs, Ely, and R. P. Daniel. He was Director, National Bank of the

State of Florida; Director of Florida State Park Association; and member of the

Board of Trade. When J. J.

Daniel died during the 1888 yellow fever epidemic, it was McQuaid who took

charge. On June 17, 1890, City Marshal Stephen Wiggins clubbed him repeatedly on the head until he

lost consciousness. He recovered from his injuries and died of pneumonia on

February 21, 1892 at age 43. The New York

Times (February 21, 1892) noted that he amassed a moderate fortune largely

through his wholesale flour and grain business. He also invested in orange

groves in central Florida.”[19]

McQuaid Advertisement,

W. T. Forbes in 1882 was the Assistant Land

Commissioner, Florida Land and

Improvement Company which owned some of the Disston Lands. In 1881, acquired 4

million acres about which 30,000 are in Duval County. Later, he became

Commissioner. By 1885, he headed W. T. Forbes & Company, part of the

Florida Real Estate Exchange on Bay Street in Jacksonville. The Exchange sold

land throughout the state.[20]

In 1882 as well he was a Director of the Georgia and Florida Midland Rail Road. Two years later he was a Director of The

Florida Investment Company in Jacksonville along with Hamilton Disston as well

as the San Pablo Diego Beach Land Company, again with Disston. In 1886, he was

a Director of the St. Augustine and Atlantic Railway Company.

W. A.

McDuff/MacDuff was native of Pictou, Nova Scotia who moved to Jacksonville

shortly after the Civil War. He began as a carpenter and became a general

contractor. He was the contractor for the Florida School for Blind, Deaf and

Dumb in St. Augustine, Florida which was built in 1884. The first four

buildings cost $12,749. He was involved in the early development of the Port of

Jacksonville. In May, 1882, the Springfield Company was formed by several

prominent Jacksonville citizens, including S. B. Hubbard, Jonathan Greeley, and

William MacDuff. They acquired the

remaining six hundred acres of the Hogans' Donation and, coupled with the

extension of the trolley line out Main Street (then known as Pine Street),

brought about the first real surge of development in Springfield. Like other

men in this group, he served on the Executive Committee of the Jacksonville

Auxiliary Sanitary Association; his term was in 1889. After the Great Fire in

1901, he developed the new suburb of

Ingleside Heights, next to Riverside and Avondale.[21]

Richard P.

Daniel was a physician. In 1882, he was on the staff of St. Luke’s Hospital. He

was a President of Duval County Medical Society. Because he played an important role later, more biographical

material will be presented in Chapter lV.

With such a strong Board of

Directors, Burbridge proceeded to get the short-line railroad planned, financed

and built as well as getting the beach community created. The directors chose

the south bank of the St. Johns River, that is, the city of South Jacksonville,

as the western terminus because of its close proximity to Jacksonville center,

a ferry, and to the best route to St Augustine and the east coast. The

Jacksonville, St. Augustine and Halifax River Railway Company would open in

1883 nearby.

Burbridge, in an editorial in the Florida

Times-Union on June 24, 1883, made a case for support, announcing that

$80,000 of the needed $100,000 had been raised. He thought that the directors

would not call for the whole amount of stock subscribed because the assessments

would not exceed 50%. The railroad be fifteen and one-half miles in length; the

cost of the equipment and tracks would be $90.000. The company would build a

town on the 700 acres owned on a “high and elevated plain” on the coast. No

swamps existed for miles, he said. He asserted that the railroad owned four

miles of land on the coast. At the end of July, the amount was reduced to two

miles. He also asserted that the corporation owned about 30,000 acres (worth

about ($90.000) donated by the state government and this land would be

worth$5-10 an acre.[22]

He estimated that the corporation would sell a thousand lots at not less than

one hundred dollars per lot, thus yielding $100,000. Thus, he was arguing that

investing in the corporation would be very profitable for investors but also

for Jacksonville because a fine resort to be created meant that the best

citizens would no longer go north in summer to escape the heat and humidity. It

would prove that Florida was safe in the summer.[23]

Initial plans changed as the

directors encountered obstacles. Schumacher went North to find the money and

men to build the little road. He learned that the J & A could not afford a

railroad running on standard gauge track (4’ 8.5”) but that a narrow gauge road

on two feet track at a length of sixteen miles could be built for $60,000 and

would be cheaper to operate. Of course, it could not connect to standard gauge

railroads but that mattered not at all

since it was to serve the planned resort. So Schumaker consulted a railroad

builder in Massachusetts. Further complications became apparent at the July 30th

called meeting of stockholders in Burbridge’s office. They elected Burbridge as

president and Ely as secretary. Burbridge announced that the corporation was

capitalized at $120,000, owned seven hundred acres of land at the beach with a

front of two miles, and had been promised 16,500 acres by the state government

upon completion of the railroad. Daniel read the opinion of Colonel John T.

Walker of the Cockrell & Walker law firm that the directors had no

authority to change name from Arlington and Atlantic Railroad Company to

Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad Company as they had done and the

stockholders could by creating a new corporation. So Daniel, Walker, and

Schumacher were appointed to draft the articles of association and by-laws

to be submitted August 2nd.

Burbridge was instructed to prepare a book of shares to be signed by the

stockholders, to wit, Burbridge, R. P. Daniel, M.D., Schumacher, Henry

Clark, L’Engle, Hubbard, Greeley, J.J. Daniel, Griffin, McQuaid, MacDuff, Ely, and Ledwith

to be sent to Tallahassee. Elected as Directors. The next meeting

was August 1st in Burbridge’s office at 4 PM. [24]

Little was

definitive at this point. The road bed was being graded and bridges built

across Little and Big Pottsburg Creeks. The 1918 map shows the railroad as the

Florida East Coast Railway, the successor to the J& A. Little Pottsburg

Creek goes through Spring Glen; Big Pottsburg Creek meanders through Hogan. It

is not clear to which creek the grading of the road bed had reached. Progress

were being made. Burbridge thought lot sales at that point would produce enough

revenue to pay road grading costs.

The railroad bed crossing Big and Little Pottsburg Creeks,

1918.

J&A route

On August 3rd,

they regularized to corporation’s status. The majority of the stockholders met

and approved the new by-laws with changes and the articles of incorporation

were sent to the state capital in Tallahassee.

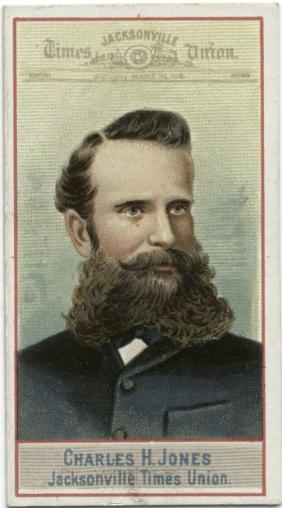

Charles H. Jones, owner and editor of the Times-Union, moved to give

five acres of centrally-located land to anyone who would build a hotel of at

least fifty rooms and a dining room capacity for one hundred people. Jones

understood that tourists and day-trippers were necessary to support the

railroad and that necessitated a fine hotel as a draw.

The stockholders meeting adjourned until August 7th

and the directors meeting was convened, necessary because of the new

corporation. They elected Burbridge as President, J. J. Daniel as Vice

President, Ely as Secretary, and Schumacher as Treasurer. They decided to ask

the stockholders to raise capitalization to $125,000 and to issue $50,000 worth

of bonds at once. On August 6, 1883 articles of incorporation filed with the

Secretary of State and Letters patent issued. [25]

Charles H. Jones

Jones, who avidly supported the J & A railroad project

with the newly-formed Times-Union, enjoyed prestige in literary and journalism

circles. Harper’s Weekly, Eclectic Magazine, Appleton’s Journal, Jacksonville Union, and then the Florida Daily Times November

1881 and the Times-Union in 1883 when he combined it with the Union, another

Jacksonville newspaper. He later began editor of the Post-Dispatch in St. Louis, Missouri and then the New York World before he died in 1913. He was elected President

of the National Editorial Association. He wrote Vers de société selected from recent authors (1874), Lord

Macaulay: His Life-His Writings (1880),

Famous explorers and adventurers in Africa: From the earliest period to the

present time, Vols. I & II, and

other books and articles. He was born in Talbotton, Georgia in 1849, served in

the Civil War as a drummer boy at age fourteen, and then entered journalism.

This very talented man became editor of Eclectic

Magazine at age twenty-one. Always an activist in the Florida Democratic

Party, he played a major role in writing the national Democratic platform of

1888, 1892, and 1896.[26]

The railroad needed

a cheerleader in Jones' Times-Union;

its reports of the construction progress reassured investors and the reading

public alike. On December 31, 1883, in an article entitled “A City By The Sea,”

its readers enjoyed details. The western terminal was in South Jacksonville a

little east of the wharf of the Jacksonville, St. Augustine and Halifax River

Railway. As the track left the South

Jacksonville terminus, it paralleled the Jacksonville, St. Augustine and

Halifax for a quarter mile and then turned sharply to the east. To cross Little

Pottsburg Creek about a mile above its mouth, it used a 10 feet high trestle

and about two miles further east it crossed Big Pottsburg Creek on a 200 feet

long trestle 15 feet high. To reach Pottsburg Creek, the construction crew had

to cut though a 60 feet ridge three quarters of a mile west of the creek. The

cut averaged 10 feet deep but was 18 feet deep in places. Once it was fourteen

miles from the ferry landing, it would cross the salt marshes on both sides of

Pablo Creek for a mile. The track was to be laid on a bank five feet high and

almost 2,000 feet long. Grading the

road bed began during the first week of

October. Between one hundred and two hundred men were doing the work, so the

grading had reached eight miles east of the St. Johns River. The grading contractors

were William Mickler, civil engineer & surveyor, and his partner Mr.

Genovar, both of St Augustine. [27]

Building a railroad, with onlookers

Time passed and the construction of the rail bed continued

into the Fall of 1884. Equipment was

ordered. Some lots at the beach site had been allocated. Griffin had gotten

title to two, for example. Plans to sell the remaining lots were made for the

company needed people there to generate traffic as well as money. By October

21, 1884, the Florida Weekly Times reported

that an artesian well had been sunk 350 feet to provide water for the

settlement and that the rail road bed had been graded but the crossties and

iron rails had to be placed. January was the expected completion date. This

photo from the collection of the Beaches Museum and History Park may have been

taken when the work was being done. Regardless, it indicates the process. Black

men are doing the heavy work.[28]

Newspapers also reported that the railroad company would auction lots on November 12 at Pablo

Beach and that potential buyers could pay $1.50 to travel on the steamer to

Mayport and then proceed on the beach to the settlement. The highest bidders would have first choice.

The remaining lots would be offered for sale in Jacksonville beginning the next

day. The J & A ran an ad in the Times-Union

specifying that the terms of the sale would be one-third in cash and the

balance in thirty days or the buyer could give his approved note for three or

six months at 5% interest. W. T. Forbes and H. S. Ely were the Committee of

Sale. Like all such advertisements, this one was enthusiastic with large type

proclaiming Pablo Beach to be “The Finest Beach in the World” sixteen miles

from Jacksonville. Maps of Pablo Beach were available to prospective buyers.[29]

So men made

the trip to the site for the auction; most were stockholders and/or directors

of the corporation. All were men of

substance; their imprimatur was important to get non-stockholders to buy. So

directors Hubbard, McQuaid, Burbridge, Forbes, Hazeltine, Ely, Hartridge,

Jones, and Schumacher went. They were joined by Dr. Hy Robinson, city alderman

M. C. Rice (who sold flour, hay, and provisions), City Treasurer Jacob Huff,

Captain John T. Talbott (of Coloney & Talbott), Dr. Seth French(hotelier),

Julius Hayden (who would be General Superintendent of the railroad), W. A.

Gibbens (meat business) , Stephen H. Melton (fish, oysters, and a saloon),

Porcher L’Engle (son of F. F. L’Engle),

and Thomas McMurray (city bill post, livery and stable business). Lots had a

set price which varied by proximity but bidders could pay a premium to get the

lot or lots they wanted. Thus Burbridge ran premium up to fifty dollars and

bought four lots. The premiums on other lots ranged from five to twenty-five

dollars. Buying lots were Burbridge, Robinson, McQuaid, Huff, Forbes, Hazeltine,

Ely, French, Hartridge, Gibbens,

P. P. L’Engle, and Jones. The auction sold 34 lots for a total of $7,514 for an

average of $221 a lot. Subsequent sales would take place in Burbridge’s office.[30]

The Times-Union painted a glowing

picture of the site. Between the ocean and the proposed settlement was a

barrier of 15-20 feet high sand dunes but the land to the west was a treeless

plain. The 1898 photograph below shows the U.S. Army at Pablo Beach and the

height of the dunes. The railroad company owned miles of oceanfront. To make

the site attractive, the company had drilled an artesian well for a water

supply, set aside land for a resort hotel, reserved two blocks for public

parks, and laid out the streets. A 250-foot wide street, the Boulevard, would

run to the ocean with additional numbered streets; perpendicular to the

Boulevard and streets would be avenues named after counties. African Americans

would be given access to the beach via Third Street about a mile to a railroad

spur.

1898 Pablo Beach , 2nd Virginia Volunteers

The Times-Union continued to plug lot sales in the guise of

news. It asserted that the excursion and auction generated interest; some

potential buyers went to Burbridge’s office to examine the plat. Ten lots were

sold. The article promoted sales by noting that the revenue from the sales

would be ploughed immediately into improving the town. Sand dunes would be

removed, streets graded, and lots improved. The sooner one bought a lot, it

said, the greater the choice would be! The board of directors had begun talking

to hotel men to find one who would erect a luxury hotel on the oceanfront close

to the railroad terminal. By July, 1885, they had reached agreement with the

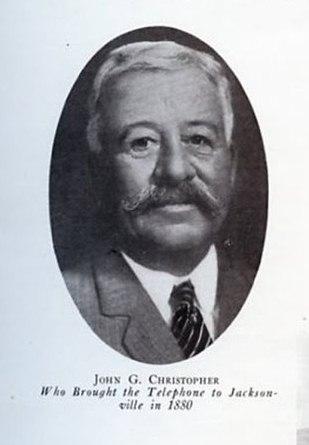

prominent and wealthy John G. Christopher of

Wrightman and Christopher to build a one hundred room hotel. Christopher chose Fred P. White of New York City to be the

architect. He promised that the hotel would equal any in the South. It would be

three stories high with a billiard room, a bowling alley, bath rooms, lounges,

and other amenities.[31]

John G. Christopher

Selling

lots proved difficult as long as train service to the beach did not exist; the

company turned to the firm of Barrs, Hunter, and Stockton to be land

commissioners in 1885. Telfair

Stockton went to the beach and sold some lots and then another when he returned

to Jacksonville. It was slow going even though the lots were selling for

$50-$250. Cottages could not be built until the train could get there with

lumber and other building materials. Once houses existed, lot sales would be

much easier. Only between four and five

miles needed to be laid. By Thursday, July 23, the Times-Union was reporting

that the track should be laid by Saturday, the 25th if heavy rains

stayed away. Patrick McQuaid and James

P. Taliaferro rode the train on an inspection tour to Pablo Creek reporting

that the ballasting for the tracks needed another two weeks to be completed

before timber could be shipped. The locomotive had been shipped from

Philadelphia and J. McElroy went to Dayton, Ohio to buy rolling stock.[32]

Taliaferro

was an up and coming man who was near to being thirty-eight years old when he

made that inspection tour with McQuaid. He was born in Orange, Virginia on

September 30, 1847, served in the Civil War from 1864-65, and then moved to

Jacksonville in 1866 when he was nineteen, more or less. He rose in business

circles, becoming a partner in the

Ambler and Taliaferro Company, lumber dealers and railroad contractors. He,

along with McQaid and J. N. C. Stockton, were directors of the National Bank of

the State of Florida. He, McQuaid and Burbridge served as directors of the

Florida State Park Association. His crowning achievement was being a US

Senator, 1899-1911, from Florida. More immediately for our story was his being

elected a director of the J & A in 1887.

James P. Taliaferro

James P. Taliaferro

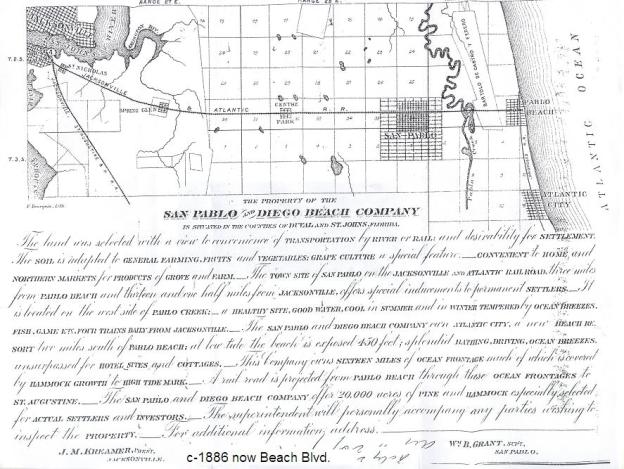

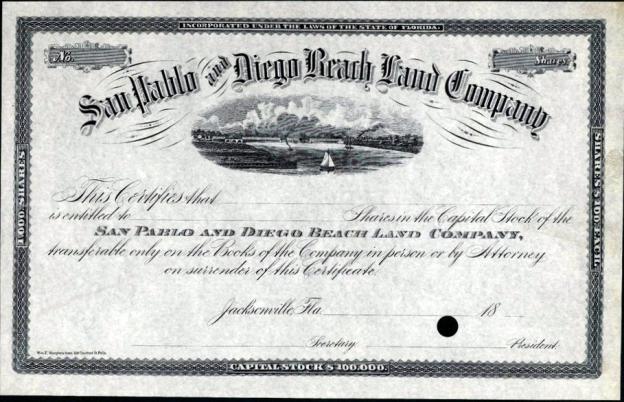

The railroad spurred the creation of the San Pablo Diego

Beach Land Company in August, 1884. The company, part of The Disston Land

Company, advertised that it had 20,000 choice acres which were the “projected

Town Sites of San Pablo, Diego Beach, and St. Leonard’s-by-the-Sea. SAN PABLO

is on the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad, thirteen miles from Jacksonville,

and within three miles of the new seaside resort, ‘PABLO BEACH.’" San Pablo was west of San Pablo Creek and

its train station or flag stop was about where Beach Boulevard and San Pablo

Road are today. Diego Beach never developed; it was what is now southernmost

Jacksonville Beach, Ponte Vedra Beach, and Palm Valley (Diego Plains). Town

lots were to be sold for $50 to $100 each and parcels from five and ten acres

would be sold for $10 to $20 per acre. W. T. Forbes was the land commissioner. In

1886, The Florida Dispatch ran the

company’s advertisement directed to

“Settlers and Investors” offering fruit and vegetable lands, home sites, and

town lots at San Pablo and Atlantic City on the installment plan if desired.

Railroad and daily mail service existed it bragged. Those interested were to

contact James E. Kreamer in care of the Bank of Jacksonville or W. B. Grant,

Superintendent. San Pablo, Florida. In

the 1887 Jacksonville city directory, Kreamer was listed as engineer and superintendent, Atlantic and Gulf Coast

Canal and Okeechobee Land Company, another Disston Land Companies. The ad

continued for a number of issues.[33]

Courtesy of Cleve Powell. San Pablo and Diego Beach Company

Stock certificate, San Pablo and Diego Beach Land Company

The Duval County commissioners, in a seventy-page booklet

promoting the county to people in other states, devoted a full page in praise

of Pablo Beach and the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad company. It asserted that the beach width varies from

200 feet at high tide to 500 feet at low tide and was so hard packed and smooth

that one could drive from Mayport to St. Augustine. The company was planning to

level the high sand dunes and use the sand to fill low places in the western

part of the town site. After the sand dunes are cut down to eight feet above

the high water market, the company will create a drainage system. To protect

the bluff from erosion, rows of piling will be driven into the sand, projecting

six or eight feet. The commissioners asserted that people could swim or “bathe”

because the average water temperature was 78° and rarely too cold in the

winter! The goal was to make Pablo Beach both a summer and winter resort. Moreover, they said that there was no

undertow and, therefore, no need for life saving.[34]

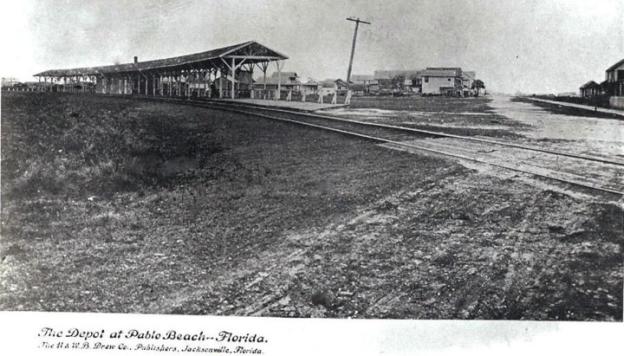

The page described plans for the central part of the

settlement noting that it had been surveyed and mapped with streets running

north-south and avenues east-west with the wide boulevard on the town front.

The expectation was that this boulevard would be planted in grass and trees

and, in front of each block, bath houses with three compartments each would be

built. The general passenger station or terminal “will be located at the corner

of Duval Avenue [Beach Boulevard] and First Street, and the entire block

immediately on the south of this is reserved for hotel purposes, and upon that

on the north will be erected a large ornamental, covered pavilion, for the

accommodation of excursionists.”[35]

Pablo Depot looking east. The road was Railroad Avenue, now

Beach Boulevard

Pavilion plans were advertised in a Times-Union article on July 29, 1885 to generate and sustain lots

sales at Pablo Beach. The pavilion at the terminus of the railroad, designed by

the forty-six year old Vermont native, the architect H. B. Bebbe, was to be

massive. It would occupy 170 feet of beach frontage. Each end would have a four

and one-half veranda. It was to be sixty feet wide with covered verandas of

nine feet on each side. The roof would be an open truss with support posts down

the center. The structure would be sixteen feet high but peak at thirty-five

feet at the center. Because of the proximity to the ocean and water being

driven inland, the building would be four feet from the ground on heavy brick

piers. The most striking feature would be an octagonal tower seventy-five feet

high topped by a flagstaff. There would be two rooms, forty feet in diameter

with large windows, in the tower fifty feet from the ground and an observatory

seventeen feet in diameter. To protect people from rain and wind, the pavilion

would have sliding doors for one third of the sides. For entertainment a

bandstand, five feet above the floor, was planned.[36]

August was not the best month for the

railroad. Old Sergeant Engine No. 1 of the Jacksonville, Halifax, and St

Augustine Railway came to Pablo Beach terminal, creating great excitement for

its arrival proved the efficacy of the rails. More people had become

interesting in the beach. David H. Kennedy, a civil engineer was laying out the

town of Neptune for Eugene F. Gilbert ,

a jeweler. Gilbert would eventually

build Neptune Station on Ocean and Atlantic Boulevards to get the Florida East

Coast train to stop. The boundary between present-day towns of Atlantic and

Neptune Beaches was not definitive. In late August, a strong storm from the

northeast hit the community with winds in excess of sixty miles an hour. The Times-Union reported the August 25th

events as “The Hurricane at Ruby” (the post office was originally called Ruby

Beach) but Hurricane Dora in 1964 is the only hurricane to have hit

Jacksonville. Regardless, the storm destroyed recently-built barracks for

railroad workers and blew down the seven tents of General Spinner’s Camp

Josephine. Fortunately for the Spinner

entourage, William and Eleanor Kennedy Scull had built Dixie House to replace

the tent where they and their daughter had been living since October, 1884 when

had had come as part of his father-in-law’s surveying crew. The frame shook and

rocked and wind and water pierced crevices in the walls but the twenty-nine

people inside were safe. Cleaning up after the storm delayed all else.[37]

Things improved for the company and Pablo Beach in the Fall.

On October 19th, the J & A was scheduled to be opened for

passenger service with the train leaving South Jacksonville (Jacksonville on

the printed schedule) at 9:00 AM and arriving at Pablo Beach at 10:25, then

returning to Jacksonville at 10:55 AM and arriving at 11:50 AM with a second

round trip run leaving Jacksonville at 5:30 PM and arriving at Pablo Beach at

7:30 PM with a return at 9:00 PM arriving at 10:00 PM. The train was initially slow, taking a long

time to make the 16.54 mile trip. Service would improve in November when the

expected additional equipment arrived. Eventually, the company would have two

locomotives. Just after making its runs to the beach, the railroad had to be

repaired. This allowed the train to make a forty-five minute trip one way. A

week later, day trippers were paying to relax in Pablo Beach. Those buying

round trip excursion tickets in South Jackson paid half-price; the company was

encouraging people in Jacksonville to go to the beach but those buying in Pablo

paid full price since they needed little incentive to go home. Freight was being shipped both ways with

Yulee Mickler shipping freshly-killed ducks to Jacksonville. The pavilion had a

floor of 64 feet by 105 feet and was near completion. Christopher’s workmen had

graded the hotel grounds and awaited the arrival of building materials by train

and by December 1st were

busily at work. A few lots were sold but not as many as possible because many

lots had not been laid out.[38]

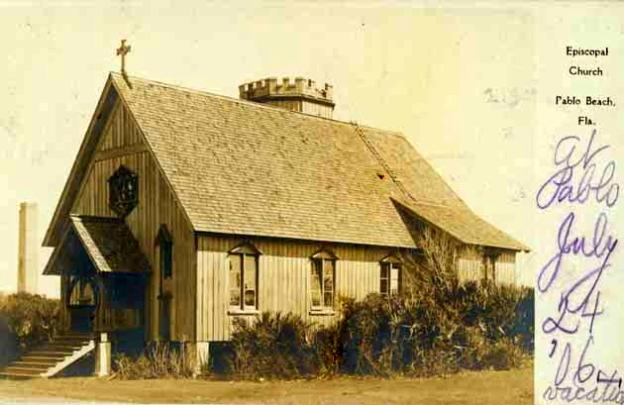

A terminal,

a pavilion, a well, a hotel under construction, and a few houses did not a

community make; it needed a church. The J & A authorized Colonel John E.

Hart, chairman of its Land and Improvement Committee, to invite religious

congregations in Jacksonville to build a house of worship on a lot supplied by

the railroad. The railroad offered to transport all the building materials for

free. The

Christophers were congregants of St. Johns Episcopal Church in Jacksonville

and, once it was complete, allowed Sunday afternoon services in the hotel

parlor. St. Johns sponsored the mission church, St Paul’s-by-the-Sea, which was

built at what is now 2nd Street South and 2nd Avenue

South in 1887. The congregants provided funds. Henrietta Christopher bought the

first organ and she and her husband were avid supporters of the little chapel.

Church services were held in the summer for the most part and priests came when

possible.[39] The

original building has survived albeit without its tower and has been moved

three times, the last in 2012 to the grounds of the Beaches Museum and History

Park in Jacksonville Beach. It is being restored. The Roman Catholic Diocese in

St. Augustine would build its St Paul’s Catholic Mission on 1st Street South by

1890 with Father William Kenny in charge.

Hart was

another important man in business and railroad circles. He was a wholesale

seed and grain dealer who owned the St Johns elevator and hominy mills by 1884,

the year he was elected a Governor of the Board of Trade. In 1886, he was a

director of the St. Augustine and Pablo Beach Railroad Company. In 1886 and

1887, he was Vice President of the Board of Trade. By 1887, he was as a

shipping and commissions merchant and an agent for Baltimore Packets.

St. Paul’s-By-The

Sea, 1906

Trains

shuttled between South Jacksonville and Pablo Beach with regularity in 1886

while necessary adjustments were made. O. H. Wade deepened the artesian well.

Daily mail delivery became routine. So many day trippers had come to Pablo on

April 4th that five coaches were needed to return them to South

Jacksonville that night. Freight also

moved between the two cities. The State had deeded 12,067 acres of “Swamp and

Overflowed Lands” to the J.& A. on

19 February, 1886 “in consideration of the completion of the railroad from

Jacksonville to Pablo Beach”. At the May 27 meeting of the Directors,

Schumacher became President of the railroad. Hart, Taliaferro, and J. M. Barrs,

Secretary of Board of Directors were newer members. They joined the other eight

directors and Schumaker in resolved the erect a first class restaurant just

north of pavilion and a couple of Chinese pagodas. They received the news that

telephone poles and wires had been strung two miles along the railroad right of

way for two miles so far. From April 1st through May 27th,

$11,000 worth of lots had been sold.[40]

James P. Taliaferro

became a very important man in Jacksonville and then became a United States,

1899-1911. He was born in Orange, Virginia on September 30, 1847; served in the

Confederate army in 1864-65; and moved to Jacksonville in 1866 at the age of

19. He worked hard and made important friends. He became a director of the

National Bank of the State of Florida along with John N. C. Stockton and

Patrick McQuaid. He and Daniel G.

Ambler of the banking house of Ambler, Marvin, and Stockton were

partners in Ambler and Taliaferro Company, lumber dealers and railroad

contractors. Along with Burbridge and McQuaid he was a director of the Florida

State Park Association.

John M. Barrs was an attorney in the offices of Fleming and

Daniel and secretary-treasurer of the J. M. & G Railroad. He would be city

attorney. In the early 20th century, he became a political ally of

Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, future sheriff and governor, and John N.C. Stockton

( who would also be involved in the J & A). Barrs and Broward were active

supporter of the Cuban effort to gain independence from Spain. These liberals

opposed the conservative faction of Taliaferro, men who were seen as lackeys of the rich and the railroads. In

1906, Barrs would author the pamphlet Municipal Ownership in Jacksonville,

Florida.

The 4th of July proved to be a big boom for the

beach and the railroad as thousands went to celebrate U.S. independence. The

unfinished Murray Hall Hotel hosted soldiers at a discount. The trains ran full

as 4,000 people came to Pablo Beach. Many African-Americans participated,

including two militia companies. They were not treated as equal participants.[41]

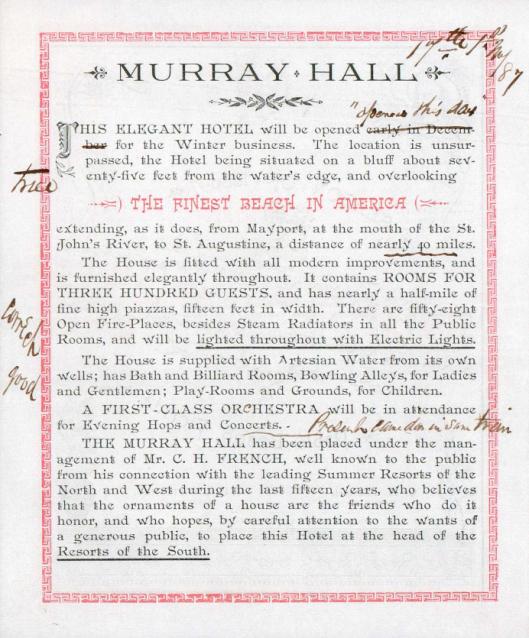

The opening of the Murray Hall heralded the arrival of Pablo

as a tourist destination; the railroad and hotel hoped these would be wealthy

customers from northern climes, the kind who had been coming to Jacksonville

and cruising upstream on the St Johns River into the interior of the state. The

flyer below describes the luxuries available, including the local post office.

The photograph shows the massive and ornate wooden building. All was finally in

place.[42]

Ad for Murray Hall Hotel Opening

Murray Hall Hotel

Pablo Beach

had both permanent and seasonal residents. Although the railroad men and

hoteliers hoped visitors would come in the winter, most went to the beach

between mid-April and mid-September. They sought sand and surf and ocean

breezes which relieved them from the very hot summer sun. This was true of

those wealthy enough to own or rent cottages as well as the day trippers. The

permanent residents served the seasonal residents as railroad employees, hotel

employees, cooks, skilled and unskilled laborers, and small business people.

Many hunted and fished to supplement their incomes, especially during the off

season. of Richard's Jacksonville Duplex

City Directory. identified 145

people as living in Pablo Beach in the 1887. Almost all were workers on the

railroad, in hotels, restaurants, and bathhouses, servants, or owners of small

businesses. Of these, 33 (22.8%) were identified as African American (colored

being the term used). Pablo Beach

residents were there to service the Jacksonville cottagers and the tourists who

were mostly day trippers. The tiny community remained small. There were only

249 people listed in the 1910 census.

The

railroad did not generate enough passenger and freight traffic; it lost money. Poor’s Manual of the Railroads of the

United States, the source for

railroad information, provides a glimpse of the problem. It ran from South

Jacksonville to Pablo Beach with a total track lineage of 17.3 miles which

included two miles of sidings. The track was 35 pound steel rails with a gauge

of three feet. It owned two locomotive engines, five passenger cars, one

combination car and twelve freight cars (two box cars and ten platform cars for

a total of eighteen pieces of equipment.

It earned $27,400.72 (passenger $20,105.06, freight $7,310.66 but spent

$35,661.62 (transportation, $13,456.96 ; maintenance, $5,969.71 ; general,

$16,234.95), thus running a deficit of $8,200.90. It paid $2,205 interest on

bonds and $2,152.15 interest on other

debt, thus raising the total deficit to $12,558.05. It received an income of

$47,266.13 from such items as land sales and rents. Its current accounts was

$1,652.38 ; bills receivable, $3,125.40 ; and cash, $97.63. Only $82,100 in

capital stock was subscribed but less, $78,975 was paid in. “The company has a State land grant of

30,000 acres, and owns besides about 2,000 acres, acquired by purchase, on

which stands the town of Pablo Beach.” It needed to sell land. It desperately

needed to stop bleeding money. [43]

Schumacher,

who had become President, tried to solve the problem. His directors, elected

January, 1887 were Hubbard, Ely, Barrs,

James W. Fitzgerald, Benjamin P.

Hazeltine, R. P. Daniel, MacDuff, Taliaferro, Burbridge, McQuaid, Forbes, and

Hart.

Fitzgerald was captain of the steamer “H. B. Plant” in 1882

and, in 1887.Superintendent of the People’s Line of Steamers and the Plant

Steamship. He was born in England in 1839 and came to Portsmouth, New Hampshire

as a child. Not long before the

outbreak of the Civil War, he moved to Charleston, South Carolina where he

captained a steamer. He moved to Jacksonville and became friends with

Taliaferro. About 1890, he moved to Tampa to design steamships for Henry B.

Plant, the Florida railroad tycoon. He invested in real estate.

Benjamin P.

Hazeltine was a partner in 1886 in the firm Drew, Hazeltine, and Livingston

which sold building materials, ice, hay, marine railway, cement and lime. They were owners and agents of vessels

running north and east and had a shipyard. In 1894, he would become the Vice

President of the Jacksonville &

Atlantic Railway which had been formed in 1893. In 1896 he owned the Arctic Ice Company

and became President of the Jacksonville Ice Delivery Company.[44]

Events forced the railroad into bankruptcy in 1890. Much of

the Duval County population fled to avoid contracting yellow fever epidemic of

1888. There were 4,676 cases; J. J. Daniel died while trying to help victims.

It started on July 28th without warning, sickening rich and poor alike, and

killing and killing. Many died. There seemed to be no stopping it, no cure.

People fled if they could. Death was everywhere. The city's population dropped

from 130,000 to 14,000. Dwellings flew yellow flags to warn of the presence of

yellow fever. Almost no one understood the disease. Frost came on November 25,

1888 and killed the mosquitoes, which were the disease carriers. Train traffic

almost ceased; the J&A lost money. Then the resort hotel on which the railroad

was banking ran into trouble. The Murray Hall Hotel was struck by a tornado on

September 23, 1889, killing a boy, wreaking destruction, and forcing it to

close for the season. Then, on August 7th, 1890, the hotel and surrounding

buildings went up in flames.[45]

The creditors of the Jacksonville and Atlantic Railroad

foreclosed and the corporation filed for bankruptcy. On December 5, 1892 was

sold by Special Master to Mellen W. Drew who deeded it to the Jacksonville and

Atlantic Railway Company on January 18, 1893, eight days after it was formed.

The Railway took over the assets and liabilities of the first J&A but with

a reduced debt load. Its story will be told later after that of the

Jacksonville, Mayport, and Pablo Navigation Company, a rival road.

[1]

According to Jack Pate, the

Archibald Abstract Books (Ofc. No. 23203) show that two waterfront lots were

deeded to George B. Griffin on Nov. 1, 1884 by board resolution.

[2]

B.W. Suckow and John Y. Smith, Madison City Directory, a

city and business directory for 1866 (Madison. B. W. Suckow, 1866).

[3]

The Panic of 1873 lasted until 1879; it was a severe

depression.

[4]

C. A. Rohrabacher, Live Towns and Progressive Men of Florida.

Jacksonville, Florida, Florida

Times-Union Publishing Company, 1887.

Pp. 26-29.

[5]

C. A. Rohrabacher, Live Towns and Progressive Men of Florida.

Jacksonville, Florida, Florida

Times-Union Publishing Company, 1887.

Pp. 26-29. Webb’s Jacksonville

and Consolidated Directory (Jacksonville: Wanton B. Webb, 1887), p. 116.

[6]

S. Paul Brown, The book of Jacksonville: a history; Poughkeepsie,

N.Y.: A.V. Haight, printer and bookbinder, 1895, 194 pages.

[7]

National

Cyclopedia; Jacksonville Public Library, Owl's Nest: Special Collections Newsletter July/August 2011; Live towns and progressive men of Florida. Jacksonville, Florida, Florida Times-Union

printing and publishing house, I887;

Paul S. Brown, The

book of Jacksonville: a History;

Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: A.V. Haight, printer and bookbinder, 1895,,

[8]

As we see below, the directors were

acting without proper authority.

[9]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_Jackson_Affair

[11]

Sterling Price's Lieutenants

(Peterson, McGhee, et al.); Biographical Souvenir of the States of Georgia

& Florida (1889, Battey & Co.), Confederate Veteran Magazine (Sept

1918), Serving With Honor (Banasik, p.378-80); Lee's Colonels (Appendix, Robert

K. Krick); Florida Times-Union (Saturday, November 26, 1892). A genealogist who

uses the moniker tinman1861 on

Ancestry.com provided the comments about the census data, See his [Mark] 9 Aug

2004 posting on John Quincy Burbridge at http://boards.ancestry.com/thread.aspx?mv=flat&m=385&p=localities.northam.usa.states.missouri.counties.pike.

"United States Census, 1880," index, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/MXVL-1HW : accessed 16 Aug 2012), J.

Burbridge, Alton, Madison, Illinois; citing sheet 185A, family 0, NARA

microfilm publicationT9-0233. Kip

Lindberg posting on Ancestry.com on

December 16, 1999.]

[12]

Webb’s

Jacksonville, Florida Directory, February, 1882.

[13]

Jack Pate, “Founding Father John Q.

Burbridge,” Tidings. Vol. 16,

No. 4 (October 1995). Griffin

would own a trolley and real estate company, the Suburban Railway and Land

Company, beginning in April, 1884. The story of Hamilton Disston and the

Disston Land Purchase is told in several places. See Frederick T. Davis, "The

Disston Land Purchase". The Florida Historical

Quarterly 17:3 (, (January

1939), pp. 201–211; J. E. Dovell, “The

Railroads and the Public Lands of Florida, 1879-1905", The Florida Historical Quarterly 34:3 (January, 1956

), pp. 236–259.

[14]

Theta Delta Chi, The Shield, Vol., 17

(1901). Florida

Times-Union and Citizen ( October

14, 1901). U.S. Census, 1850, 1860. 1870.

[15]

The

National Cyclopedia of American Biography, p. 137; S. Paul Brown, The Book of Jacksonville: A History.

(Poughkeepsie, NY, 1895), pp. 158-159.

[16]

Biographical

Directory of the United States

(http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=S000737).

[17]

Wayne W. Wood, Joel McEachin, and

Steve Tool, Jacksonville's Architectural

Heritage (Gainesville: University Press of Florida,1989), p. 87.

[18]

LENI BESSETTE AND LOUISE STANTON WARREN

, “Pioneering Hubbard family's name is still remembered in Jacksonville,”

Jacksonville.com, December 10, 2005. Joseph E. Miller, “Headstone: Samuel B.

Hubbard,” The Jacksonville Observer,

June 19, 2009. As well as other references

[19]

New York Times, February 22, 1892; Leni Bessette and Louise Stanton

Warren, “From Our Past: McQuaid rose to become city's mayor, but it almost

ended badly, “ Florida Times-Union, July 9, 2005.

[20]

.John P. Varnum Jacksonville Board of

Trade, Jacksonville, Florida. Jacksonville Florida Times-Union, 1885. .

[21] Jacksonville Historic Landmark

Commission, Jacksonville's Architectural

Heritage, p. 172. Thanks to the able staff of the Jacksonville Public

Library, I was able to confirm that MacDuff’s name has been misspelled McDuff including on street

signs. See Virginia King, Interesting

Facts About Leading People and Families of Duval County 5th Ed.

(Jacksonville, 1977).

[22]

How much land the corporation got from

the public is not clear. We know that it received 12,067 acres of “Swamp and

Overflowed Lands” by 1886.

[23]

John Q. Brundidge, “Editorial,” Florida Times-Union ( June 24,

1883). It was not an editorial as much

as a plea to the public to support the project. The owner and editor, Charles

H. Jones (profiled below) was a strong supporter of the proposed railroad,

[24]

“The Beach Railroad,” Florida

Times-Union (July 15, 1883); “Our Beach Railroad” Florida Times-Union (July 31,

1883. Jack Pate noted Pate’s note that Richard A. Martin, The City Maker.(Jacksonville, R. A. Martin, 1972), p. 135, says the

corporation owned 1,700 acres at the beach.

[25]

“The J & A Railroad,” Florida

Times-Union, August 4, 1883. Report of the Secretary of State for the Years

1883-84. (Tallahassee, Florida, 1884),

p. 8.

[26]

C. A. Rohrabacher, Live Towns and Progressive Men of Florida.

Jacksonville, Florida, Florida

Times-Union Publishing Company, 1887.

Pp. 107-108; Walter Thompson,

“Biographical/Historical Note,” A Guide to the Charles H. Jones Papers,

University of Florida Smathers Libraries - Special and Area Studies

Collections, November 2008; “The

Florida Times-Union, http://morris.com/divisions/daily-newspapers/florida-Florida

Times-Union, retrieved September 5, 2012; S. Paul Brown, The

Book of Jacksonville: a history (Poughkeepsie,

N.Y.: A.V. Haight, printer and

bookbinder, 1895), pp. 127-130.

[27]

“A City By The Sea,” Florida Times-Union (December 31, 1883).

William Mickler, a civil engineer and surveyor in St. Augustine, may have been

the one involved in the grading. St. Augustine City Directory, 1885.

[28]

Florida

Weekly Times, October 21, 1884. The image is labeled P902 in the Beaches

Museum and History Center online database.

A glimpse of the Sculls can be found in the 1939 interview with Eleanor

Scull, “Ruby Beach,” American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal

Writers' Project, 1936-1940, America Memory, Library of Congress. She has some dates wrong

[29]

The Florida Times-Union, October 21,

1884.

[30]

Florida

Times-Union, November 13, 1884. Jack Pate, “A Trip to the Beach” and “Pablo

Beach, “ Tidings, newsletter of the

Beaches Area Historical Society, 1993-2004. Webb’s Jacksonville Directory,

1882.

[31]

“Our Seaside Resort,” Florida

Times-Union, November 14, 1884; “At Pablo Beach,” Florida Times-Union, July 7, 1885.

[32]

“Jacksonville’s New Resort,” Florida Times-Union, July 17, 1885;

“Track Nearly Laid, ” Florida Times-Union.

July 23, 1885.

[33]

Duval County Commission, Duval County Florida (Jacksonville: Florida

Times-Union Printing Company. 1885), p.28; The Florida Dispatch, October 4,

1886.

[34]

The information was faulty but, after

all, it was boosterism. Not many bath in the ocean in the winter. A life guard

corps was created in 1912.

[35]

Duval

County Florida, p. 28. The terminal was a block further west.

[36]

“Pablo Beach Pavilion,” Florida

Times-Union, July 29, 1885.

[37]

“Ruby Locals,” Florida Times-Union, (August 4, 1884). The dispatch from H. G.,

special correspondent of the Florida Times-Union, is dated August 1, 1885; “The

Hurricane at Ruby,” Florida Times-Union,

August 27, 1885.

[38]

“To Be Opened Monday,” Florida Times-Union, October 17, 1885.

Julius Hayden, Superintendent of the J&A published the schedule. “At Pablo

Beach,” Florida Times-Union, October

21, 1885; “Lively Times at the Beach—Killing Time Instead of Game, “ Ruby

News—Notes, Florida Times-Union,

December 4, 1885.

[39]

Harley Henry, “A Brief History of St.

Paul's by-the-Sea,” St. Paul's by-the-Sea web site, http://www.spbts.net/our-history.php,

on March 23, 2012. Unpublished manuscript, “A Chronology of St. Paul’s by the

Sea

Episcopal

Church, Jacksonville Beach, Florida. Revised May, 2007, copy in the Beaches

Museum.

[40]

H. G., “Ruby Local,” Florida

Times-Union, March 20, 1886; “At Pablo Beach,” Florida Times-Union, April 5,

1886; “Things at the Beach,” Florida Times-Union, May 8, 1886; “By River and

Rail,” Jacksonville Morning News, May 28, 1886. Jack Pate, “A Trip to the

Beach,” Tidings, cites Archibald

Abstract Books, Ofc. No. 26109 as the

source of the land transfer.

[41]

“The Military Camp,” Florida Times-Union, July 3, 1886; “The Nation’s

Birthday,” Florida Times-Union, July 6, 1886.

[42]

The year the completed hotel opened

is usually said to be 1886 but the flyer has to printed date struck out and a

handwritten note saying May 17, 1887. Housing soldiers in July, 1886 qualifies

as an opening even if the hotel was incomplete and that fact that the post

office named Ruby Beach was moved into the hotel in 1886 and then renamed Pablo

Beach gives eight to the 1886 date.

[43]

Poor’s

Manual of the Railroads of the United States Volume 20. ( New York: New York Poor's Pub. Co , 1887). Other

payments, $73,079.93. Financial Statement, December 31, 1886. Capital stock, $100,000 ; funded debt,

$50,000, 7 per cent. 10-20-year $500 coupon bonds, interest January and July,

secured on road bed, franchise, roiling stock, and State land grant ; bills

payable, $39,588.17 ; profit and loss, $17,402.78 total, $206,990.95. Contra :

Cost of road and equipment, $134,530.12 ; real estate and buildings, $26,300.49

; stocks and bonds owned, $36,400 ; other property and assets, $4,881.93 ;

current accounts, $1,652.38 ; bills receivable, $3,125.40 ; cash, $97.63 total,

$206,990.95. Capital stock authorized, $100,000; subscribed, $82,100; paid in,

$78,975 par, $100. History. Chartered

August 25, 1882 ; road opened in 1884. Company has a State land grant of 30,000

acres, and owns besides about 2,000 acres, acquired by purchase, on which

stands the town of Pablo Beach. Annual meeting, first Wednesday after second

Monday in January.

[44][xliv]

Webb’s Jacksonville city directories,

various dates; Butchers’ Advocate And Market Journal, November 18, 1896.

[45]

On the yellow fever epidemic, Margaret

C. see Fairlie, “The Yellow Fever

Epidemic of 1888 in Jacksonville,” Florida

Historical Quarterly 19:2 ( October 1940 ), 96-109; on the Murray Hell

Hotel, see Donald L. Mabry, “What A Man! John G. Christopher”, Historical Text

Archive, http://tinyurl.com/bvgnjhp.