|

Uncovering African American Micro History in Florida

By Donald J. Mabry

Too little is known about the local or micro history of African American

residents in the United States. This is certainly true of those who have lived on the

“Beaches”—the oceanfront of Jacksonville, Florida.[1] Nor are there substantial collections of original documents

or oral histories one can consult. The Rhoda Martin Cultural Heritage Center, opened in

2007, was built to further appreciation of African American history at the Beaches but it

has few resources and its office hours are not convenient for many. The much larger

Beaches Area Historical Society (BAHS) operates on a shoestring budget and with a lot of volunteer

labor. Beaches history lacks many records, especially complete records, or runs of beach

newspapers. BAHS, established in 1978, begun collecting them but its collection of materials

is spotty; it has the only collection of newspapers published at the beach but no complete

runs. My research there has been invaluable but all of it has had to be supplemented by

private sources, by census records, published materials, and oral testimony. All of which

goes to say that we do not know much about the lives of African Americans at the beaches.

My goal with this essay is to explain what I know and provide some tools for others to do

research. The bibliography at the end of the essay will guide the reader to sources. As I

go along, I will provide many names of African Americans who have lived at the beaches so

they don’t disappear and because knowing them may help future researchers. In

addition, photos and map images are provided.

There may have been African Americans as well as whites before the building of the

Jacksonville and Atlantic railroad in 1883-85 but there couldn’t have been many. The Palm

Valley area (the former Diego Plains) was older but sparsely populated. It was the

creation of Pablo (neé Ruby) Beach that brought the people to the area.

African Americans built the railroad and worked on it as section hands and as hostlers. They helped level

the sand dunes so dwellings and stores could be built. They worked at the

livery stables and the maids in homes and hotels. According to Dianne Hagan, James Dixon,

an African American, went to Jacksonville Beach (then Pablo Beach) as a section hand for

FEC railroad. Dixon quoted as saying that as many as 200 African American men employed by the big

hotels during the “season.” Since most of the original houses (called cottages)

were owned by wealthy men from Jacksonville whose primary residence was Jacksonville,

African American servants probably went to the beach with their employers. Hagan asserts:

During the early history of the beaches, the McCormick Construction Company employed

more African Americans than any other area business. The company built A1A from Jacksonville Beach to

St. Augustine and employed many African American workers. The workers earned $1 per day, which was

not unusually low in the teens, 1920’s and 1930’s. The McCormicks maintained

separate quarters and a commissary for the African Americans employees.

African Americans also worked as domestics and handymen. They worked for the railroad which was built

to the beach in 1884. They also were employed by hotels, restaurants and boarding houses.

These opportunities for employment are probably a factor in African Americans settling in

Jacksonville Beach.

We know a little about who lived in Pablo Beach in 1887 because the historical society has

a copy of Richard's Jacksonville Duplex City Directory. Jacksonville: John R.

Richards & Co., 1887. It lists 145 persons of whom 33 (22.8%) were identified

as African American (colored being the term used). Those identified appear to be heads of

household and the occasional single person. So we can’t know who lived in Pablo Beach

from Richard’s; in fact, it asserts that there were a thousand people at Pablo

Beach but that count has to be exaggerated even for the high season in the summer when the

wealthy brought families and servants to live. After all, the one thousand figure would be

about seven times the number he actually lists. Later United States Census records do not

confirm it.

We can know the names and occupations of the African Americans Richard’s lists

but, like the whites, we have to assume that some of them had families living with them.

Someone had to stay behind when the wealthy went back to Jacksonville. This table is built

from Richard’s.

NAME |

OCCUPATION |

EMPLOYER |

Brackett, William |

2nd Cook |

Murray Hall Hotel |

Brooks, Carrie |

Domestic |

J. Q. Burbridge |

Brown, Jane |

nurse |

J. M. Barrs |

Burrow, Edward |

Waiter |

Hotel Pablo |

Carter, Willis |

Hostler |

T. McMurray |

Collins, William |

Hostler |

T. McMurray |

Columbus, Christopher |

Hostler |

T. McMurray |

Edwards, Henry |

Chief Cook |

Hotel Pablo |

Franklin, James A. |

Butler |

G. E. Wilson |

Gordon, Alice |

Cook |

John Clark |

Gordon, Mary |

Domestic |

W. A. Gibbons |

Hughes, William |

Waiter |

Hotel Pablo |

Jackson, H. Andrew |

Hostler |

T. McMurray |

Johnson, Alice |

Laundress |

Hotel Pablo |

Johnson, Daniel |

Hostler |

T. McMurray |

Lamar, Ellen |

Chambermaid |

Hotel Pablo |

Lockett, Thomas |

Servant |

F. E. Spinner |

Lotry. Annette |

Domestic |

W. B. Clarkson |

Monson, Charles |

Porter |

W. A. Gibbons |

Moses, Holly |

Carpenter |

|

Palmer, Henry |

Laborer |

|

Porter, John L. |

Manager |

T. McMurray |

Reeves, Emma |

Domestic |

J. Marvin |

Sluman, Annie |

Domestic |

H. W. Brooks |

Smith, Edward |

Second Cook |

Hotel Pablo |

Smith, Hattie |

Domestic |

G. W. Wilson |

Thompson, Nora |

Janitress |

J & A Bathhouse |

Watson, Mary C. |

Domestic |

C. S. L'Engle |

Watson, Mary E. |

Domestic |

C. S. L'Engle |

Watson, William |

Porter |

C. S. L'Engle |

Williams, Delia |

Laundress |

|

Williams, Sarah |

Domestic |

T. McMurray |

Williams, Thomas |

Drayman |

|

According to Richard’s directory, some lived where they worked; there are no records

telling us where the rest lived. Some worked for the two big hotels—Murray Hall Hotel

and Hotel Pablo--for Thomas McMurray’s livery stable, or the Jacksonville &

Atlantic Railroad. Others worked as servants to wealthy people such as former Treasurer of

the United States Francis Spinner who lived in his own tent city and John M. Barrs, a

lawyer who was also secretary of the railroad. We know that whites also worked as

servants. In the late 19th century, one had to have money to build a summer

cottage in the wilderness at least fifteen miles from places to work.

We have records for the men who organized the railroad company and were given thousands of

acres of land by the taxpayers, land which they sold to build the little railroad[2] ; after all, as the elite, they left all kinds

of records. Newspapers covered what they did. Government forms were created. Some wrote.

We have few records, however, for the ordinary people. One exception is the Scull family

because William E. and Eleanor K. Scull were among the first settlers because the family

helped survey the railroad right of way and Postmistress Eleanor named the settlement Ruby

Beach after their daughter. Years later, Eleanor talked to the Federal Writers Project, a

New Deal relief program, about their experiences. One can’t do history without

records.

We know that Henry M. Flagler hired African Americans to work on his Florida East Coast

Railway, bought the J & A, revamped the narrow gauge into standard gauge, and extended

the line to the fishing village of Mayport on the south bank of the St Johns River close

to the mouth of the river so he import coal. He also built the luxury Continental Hotel

and created Atlantic Beach. In both cases, African Americans worked for Flagler and some

lived in what became the Donner area of the settlement, west of the Hotel. Some lived in

Mayport. Some lived in Pablo Beach. Perhaps there are pay books or some other payroll

records that tell us who worked for Flagler at the beaches, when, and want their names

were. Such records probably would tell us how much they were paid.

The Florida East Coast Railway created Manhattan Beach for its African American employees.

Manhattan Beach, north of Atlantic Beach and south of the jetties, opened with pavilions,

cottages, and playgrounds. Some years later, it would be replaced by American Beach in

Nassau County to the north.

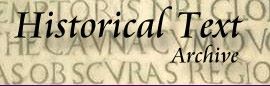

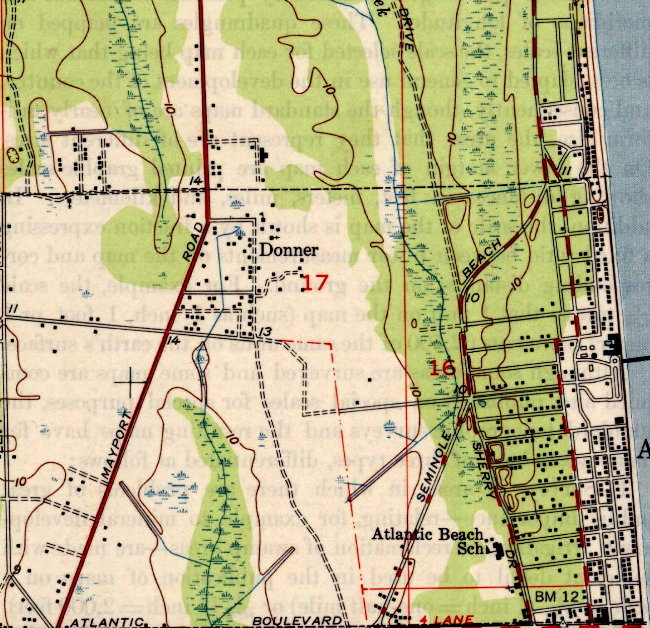

Click map for a larger image Click map for a larger image

1964 U. S. Geological Survey

Whites and African Americans were not allowed to use the same stretch of ocean beach. The Charter and

Ordinances of the City of Pablo Beach (1924) compiled by City Attorney Stanton Walker is

typical and explicit. Section 103 said:

It shall be unlawful for any white person or persons to bathe together with any negro

person or persons, or for negro person or persons to bathe together with any white person

or persons in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean within the limits of the City of Pablo

Beach.

The authors of the ordinances believed that Negro genes were much more powerful than

white genes for they defined a Negro as any person who had one-eighth or more of Negro

blood, that is, if a great grandparent was a Negro (Section 104). Then the person was a

Negro for the one-eighth trumps the seven-eighths! Together, according to Section 105, was

within 500 feet. Violators could be punished by ninety-days in jail or a one hundred

dollar fine or both (Section 105). One hundred dollars would buy 714 quarts of milk in

1924 so the fine was substantial.

Manhattan Beach was provided by Flagler’s Florida East Coast railroad for its African

American workers. The Atlantic Beach Corporation acquired it from the FEC and then Harcourt

Bull took over. Bull leased land to business people and resisted pressure for years

from white to drive African Americns away. Eventually, the state bought the land to make it a state

park.

In his letter of J. H. Payne, Atlantic Beach Corporation to FEC vice president J. P.

Beckwith. October 24, 1914, Payne wrote to tell Beckwith that the conditions of the

pavilion were worse than he had said earlier and that, within the last six weeks, the

beach had eroded 12-15 feet and that the north pavilion was now within three feet of the

high water mark. He asked the FEC to share the costs of repairing the two pavilions, the

bath house, and walkways as well as to improve the site. He estimated the cost would be

$925. He remarks that it is not the intention of the Atlantic Beach Corporation as a

“colored resort.” As it turned out, he had to write on March, 1915 that the

pavilions and bath house needed new foundations and a forty-five foot extension of

bulkhead raised the cost to $1,279.24. Payne argued that the repairs would make the site

“a creditable colored resort.” The Atlantic Beach Corporation would be bankrupt

by 1917 so maybe Payne and associates needed whatever money they could get.

Harcourt Bull ran the affairs of the Atlantic Beach Corporation by 1917 and dealt with

Manhattan Beach issues. In his letter to Lucy Bunch, June 6, 1917, he sets conditions for

her leasing the Corporation’s property at Manhattan Beach for the 1917 and possible

subsequent seasons in order to make it a “first class, respectable Negro

resort.” She was to spend at least $200 to repairs the pavilions and bath house as

part of the rent, for the property had been neglected. Bull would also get one percent of

the gross receipts and the right to inspect her books. He noted that the mortgage on the

property was being foreclosed by the Equitable Trust Company of which he was one of the

counsels and that he expected to acquire the property because he owned a large majority of

the mortgage bounds and would likely buy it. He promised Bunch that he would try to get

her a lease for 1918. He also stipulated that no liquor could be sold.

A few years later, the condition of the pavilions and bath house were again an issue as

the wind and surf continued to pound away at them. David A. Mayfield, who owned a plumbing

and heating company in Jacksonville, wrote to Bull on February 7, 1920 offering to buy the

badly damaged pavilions for $60 which he would remove. Bull responded to Mayfield on

February 17, 1920 to refuse the offer as being too cheap. He said he was working with

“colored people” with the idea of moving the south pavilion further back from

the beach and having it repaired so it could continue to be a resort for African

Americans.

On December 26, 1922 Bull filed a Notice of Lis Pendens against the Manhattan Beach

Corporation in the Circuit Court of Duval County. He wanted to be the first lien on the

Manhattan Beach Corporation mortgage foreclosure. The mortgage was for $2,500. The suit

named the property as being Lots 1, 2, 3, 4, 11, 12, 13, and 14 in Block 5 and Lots 5, 6,

7, 8, 9, and 10 in Block 8. I only have this Notice so I don’t know what happened in

this instance but do know that one of Bull’s corporations, the R-C-B-S Corporation,

acquired ownership of the Manhattan Beach property.

Bull answered Joseph W. Davin of the Telfair Stockton & Company real estate

development firm on November 24, 1932 concerning African Americans at Manhattan Beach

about which Davin had inquired in a November 9th letter. Bull said it was the

policy of the Corporation (he was president) not to sell to African Americans but leased

to them on a short- and long-term but with the proviso that said lease could be revoked if

the Corporation sold the entire property to a “developing” company. He then

asked if Telfair Stockton & Company’s client wanted such a lease. Since he noted

that some lots were owned by African Americans but that they had acquired them before the

Atlantic Beach Corporation acquired the area from the Mayport Terminal Company (a Flagler

company) many years ago.

The issue of African Americans and Manhattan Beach became more complicated when Edward

Ball, the brother-in-law of Alfred I. du Pont. His sister Jessie inherited the Florida du

Pont vast business empire when her husband died in 1935 but gave operational control to

Ball. Because of these family connections, Ball was a powerful man when William H. Rogers

(the R in R-C-B-S) wrote to Bull (the B in R-C-B-S) on January 27, 1933 in regards to

Ball’s desires for Manhattan Beach. Rogers copied John T. G. Crawford (the C in

R-C-B-S). According to the letter, Ball had just acquired title to the “Manhattan

Beach property.” He wanted to buy from R-C-B-S a strip of land 1,000 feet behind his

newly-acquired property, a statement that suggests he only bought some land not all of

Manhattan Beach. Ball was a racist and he wanted the help of R-C-B-S not only in getting

African Americans excluded from Manhattan Beach but also to get them off the oceanfront

from the southern limits of Atlantic Beach to the St Johns River. Rogers wanted to meet

with Bull, Crawford, and hid law partner C. C. Towers as soon as possible. This was

serious.

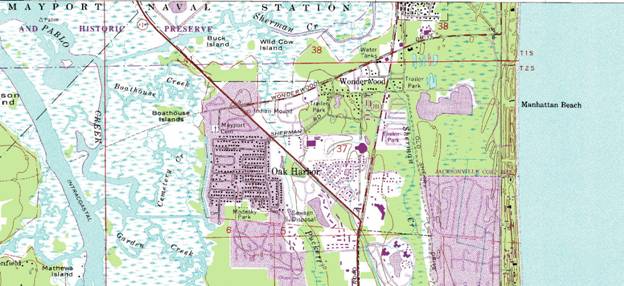

Marsha Dean Phelts, in her informative folk history, An American Beach for African

Americans wrote that the Mack Wilson’s pavilion, the last public facility, was

mysteriously destroyed by fire in 1938. She repeats the story of old-timers that the fire

was designed to drive African Americans out. She included photos from the Eartha White

Collection of the University of North Florida in Jacksonville. The Beaches Area Historical

Society also has these and other photos.

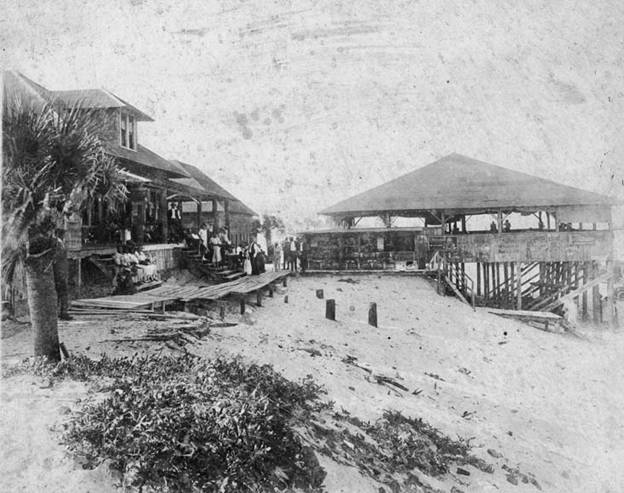

Mack Wilson Pavilion Eartha White Collection, University of North Florida.

William Middleton Pavilion Eartha White Collection, University of North Florida.

One report from the 1950s said that Negroes owned beachfront property but that the lack of

bulkheads allowed storms to wash it away. Efforts to lease land on the oceanfront had

failed.

Manhattan Beach still existed at least until 1964 as shown by this snippet of the U. S.

Geological Survey Map of 1964 and revised in 1992 and, for a time at least, was an area

where African Americans were allowed to go to the ocean. As a teenager in the 1950s, I

rode on the beach to the jetties which channeled the St Johns River into the ocean and saw

African Americans on the beach. Eventually, the State of Florida bought the land adjacent

to the south of the expanded Navy facility at Mayport and created Hanna State Park, thus

swallowing Manhattan Beach.

African Americans used the beach at Jacksonville Beach before 1964 under limited

circumstances. Baptisms were one. There was a time when they were allowed to use the ocean

on south Jacksonville Beach on Mondays. I don’t remember that being true in 1953 but

I was young.

Baptismal service, Jacksonville Beach

Someone interested and patient could plow through the property records of Duval County for

the area. Property ownership and transfers are recorded. One would have to discover if the

owners were African American or not. Such an approach would discover what happened at

Manhattan Beach. Such a study would be a good master’s thesis.

In an earlier essay entitled “WWI

Veterans: Jacksonville Beaches & Mayport ,” I identified the men who

registered for the Selective Service System (the draft) passed by Congress in May, 1917

and those who served. There were two sources: Raymond H. Banks, “Historical

Background of The World War I Draft ,” at http://archives.gov/genealogy/military/ww1/draft-registration/index.html,

World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, M1509 and the Military

Service Cards found at http://www.floridamemory.com/Collections/WWI/. I list the names of

the African Americans who registered so they are not lost to posterity and I note those

who served with an asterisk. A disproportionate number of those who serve were African

American. At least 106 men in Mayport, Atlantic Beach, Pablo Beach, and Palm Valley

registered for the draft, twenty-six of the 106 (24.5%) were African Americans. Who were

these black men? We know little about them other than what is in the table below. We do

not know why some were chosen. Those who registered for the draft are listed below; those

who served in the military are marked with an asterisk.

NAME |

BRANCH |

RANK |

PLACE |

VET |

BIRTH YEAR |

| Aiken, William |

Army |

Pvt. 1st Class |

Mayport |

* |

1895 |

| Barnes, Porter R. |

Army |

Pvt. |

Pablo Beach |

* |

1894 |

| Barnes, Samuel G. |

Army |

1st Sgt. |

Pablo Beach |

* |

1871 |

| Brooks, Clarence |

|

|

Mayport |

|

1889 |

| Coward, Clarence |

Army |

Pvt. |

Mayport |

* |

1893 |

| Douglass, Archer |

|

|

Palm Valley |

|

1894 |

| Floyd, James L |

Army |

Pvt. |

Mayport |

* |

1895 |

| Hardy, Levi |

|

|

Palm Valley |

|

1880 |

| Jackson, John |

Army |

Pvt. 1ST Class |

Atlantic Beach |

* |

1895 |

| Jackson, Robert |

|

|

Pablo Beach |

|

1880 |

| Jeffcoat, William Howard |

Army |

Pvt. |

Pablo Beach |

* |

1886 |

| Jones, Tobe |

|

|

Pablo Beach |

|

1876 |

| Killin, Alexander |

Army |

Pvt. |

Atlantic Beach |

* |

1897 |

| Kirkland, Alexander |

Army |

Pvt. |

Atlantic Beach |

* |

1893 |

| Knight, Joseph |

|

|

East Mayport |

|

1901 |

| Mincy, Andrew |

|

|

Pablo Beach |

|

1878 |

| Mosly, Edmund |

Army |

Pvt. |

Mayport |

* |

1892 |

| Nicholas, James |

|

|

Mayport |

|

1895 |

| Ruffin, Leroy |

|

|

Mayport |

|

1891 |

| Walker, Jeremiah |

Army |

Pvt. |

Mayport |

* |

1892 |

| Webb, Willie |

Army |

Corporal |

Atlantic Beach |

* |

1894 |

| Wiggins, Albert |

|

|

Mayport |

|

1890 |

| Williams, General |

Army |

Private |

Mayport |

* |

1892 |

| Williams, George |

Army |

Private |

Mayport |

* |

1895 |

| Williams, James |

|

|

Pablo Beach |

|

1879 |

The WWI Military Service cards give additional information. Those in Florida were Aiken

Webster, Samuel Barnes in Madison County, Floyd and George Williams in Mayport, Jackson in

Leesburg, Killin in Tampa, Mosly in Orange City, and Walker and George Williams

Jacksonville. Porter Barnes was born in Asheville, North Carolina and Kirkland in

Fayetteville, North Carolina. Two were born in Georgia: Coward in Westboro and Webb in

Coleman. Jeffcoat in Orangeburg, South Carolina. Aiken, Porter Barnes, Coward, Mosly and

George Williams served overseas. The cards also give induction location and dates of

service.

In 1900, a census taker noted fifty-one African-Americans within eleven families in Pablo

Beach, an average family size at the time. There were other African Americans in Atlantic

Beach and in Mayport. Since African Americans were forbidden by law and custom from

patronizing many white businesses, they created their own just as they had to create other

important institutions such as churches, insurance companies, fraternal organizations, and

clubs. Maggie Fitzroy wrote in an article about residents reminiscing in February, 2010

and their creating a list from their collective memories:

Completing the history project in time for a January social celebration called "A

Night on The Hill," they listed businesses that included two Smith Grocery stores, a

drive-in movie, a laundromat, Boston Tea Room, Crow Grocery, Georgia Boy Grill, Leo and

Ace Restaurant, Holloway Steak House, Chicken Shack, Blue Moon boarding house, St. Andrew

AME Church, 600 Club nightclub, Poor Boy Pool Room, Nelson Hayes Barber Shop, The Waiter

Club, Jabo Teenage Club, Evergreen Restaurant, Emma Branch Salon, Mr. Dixon Taylor cleaner

and taxes, Beaulia and Cathan Beauty Shop, Marcelee Salon, George and Carrie Redd Barber

Shop, Harlem Grill, Tranquil Room, Pearl Cafe, Blue Front Mary Swan, Poor Boy Cab Stand,

Charley Thomas Taylor and "Mother Rhoda's House" and the school she founded next

door on Shetter Avenue.[3]

By 1905, there were enough African-Americans at the beaches for the founding of the St.

Andrews African Methodist Episcopal Church by Mother Rhoda L. Martin in the section known

as “The Hill.” This remarkable woman had been born in 1832 and lived until 1948.

She founded St. Andrews and began teaching school at age 73. Initially, the church met in

her home at the corner of Shetter Avenue and 7th Street South, south of the FEC

railroad tracks.

The Jacksonville Beach City Council must have gotten worried about people crossing

traditional racial barriers for, in November, 1935, it passed an ordinance requiring

residential segregation and job segregation. One wonders what prompted such an action.

Government usually pass laws to address an existing problem. Or was it the traditional

insecurities that whites in the United States have demonstrated?

The State of Florida counted people in the “5” year between the US Census. In

1925, Jacksonville Beach had 744 people—544 whites, 187 African Americans, and 13 of “other

races.” African Americans were 25.1% of the population. Mayport contained 644 people, 430

whites, 214 African Americans (33.2%). Atlantic Beach was too small to be included within the

category of “minor civil divisions of the state census. By 1935, Jacksonville Beach

had 1,094 people, an increase of 695 since 1930. Of these 797 were white and 297 (27.1%)

were African American. Outside the city limits, there were an additional people of whom 359 were

white and 43 were African American. Mayport had 511 people; Atlantic Beach had 164. The state census

does not provide a breakdown by race. In neither census were the numbers very large. That

made no difference.

African-Americans did not get a public school until 1939. White kids were taught in 1887

by Mrs. James E. Dickerson, wife of a storekeeper; by 1903, it was located at 2nd

Street South and Orange Avenue (now 2nd Avenue South), located within walking distance of

“The Hill.” Segregation meant that the small student population of white and

blacks could not be educated together even though to do so made economic sense.

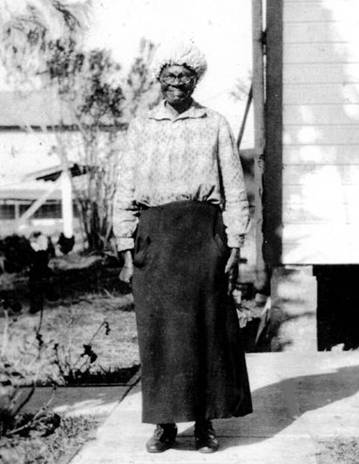

Rhoda Martin

Education was not considered important in Duval County for “white” children and

even less for “black” children. In 1900, the Duval County school system spent

$12.08 per white child but only $5.47 per "black" child. In the system, 51% of

the students were “white.” School lasted only 101 days. Salaries were low but

were less than $40 per month for "black" women. School was only for five months.

`In the 1930s, there was a school for African-Americans in East Mayport which had grades

1-6 in one room taught by Miss Short. Allison Thompson in her Shorelines article

“Reliving School Day Memories,” of October 7, 1998 wrote of Elizabeth (Williams)

Wells who recognized herself and her brother Thomas Williams in a photo of the one-room

Mayport School. She was tall, lanky, and wearing a black sweater; her brother, she said,

was half-hidden behind a classmate.

Mayport School

In 1939, the Duval County Board of Education began building a four room elementary school

for African-Americans (#144) on a two acre lot on the corner of 3rd Avenue

South and 10th Street South in Jacksonville Beach. The number of students

increased so a building was constructed in 1946. That year, it had 86 students in grades

1-6. The increase in the number of students necessitated the addition of two classrooms

and a cafeteria in 1952. By 1956, it had 217 students in grades 1-6 . The Duval County

school system operated School #115 for black students in Atlantic Beach in 1946; it had 23

students. Presumably, this school also served Mayport. Nevertheless, there were not many

students.

The Second World War (WWII) in which the United States participated from December,

1941 until August, 1945 caused demographic and economic changes to Jacksonville and Duval

County prompting the Council of Social Agencies to study the situation of African

Americans. On education, its report, Jacksonville Looks at Its Negro Community,

found wide discrepancies between the education of whites and blacks. Of the 95 black

teachers in 1945-46, 91 of them received $189 a month, the minimum even though they held

the Bachelor’s degree and had the maximum experience. By contrast, 71 of 83 white

teachers in the same category received $233 a month. Black substitutes got $4 per day

whereas white subs got $5 or25% more. This changed at the end of the 1946 year when the

Duval County Teachers Association won the suit it had filed in 1941 demanding

equalization. Per capita expenditures for white high school students in 1944-45 were

$104.53 whereas they were only $70.24 for black high school students. Similarly, for white

elementary school students it was $85.15 but $53.08 for black students.

Jacksonville Beach Elementary School # 144 was improved in 1946 when a new building was

constructed in 1946 with four classrooms. Student enrollment increased so that two more

classrooms and a cafeteria were added in 1952. For the 1955-56 school years, it had had

217 students served by 6 full-time teachers plus an itinerant music teacher. The school

was in “The Hill” section but 108 had to be bused. School #115 in Atlantic Beach

had closed. Richard H. Cook was the principal. If any child pursued education beyond the

sixth grade, it was necessary to be bused twenty-five miles to Stanton High School.

The Beaches population grew by 1945; the Second World War brought a U. S. Navy to Ribault

Bay in the tiny fishing village of Mayport and, with it, an influx of people and money.

People who worked there lived in different places at the beaches. The Palm Valley precinct

had 561 people of whom 406 were classified as white and 155 Negro (27.6%). Mayport had

1,236 of whom 881 were white and 881 were Negro. Neptune Beach had 1,298 whites within its

city limits and another 402 persons outside the city limits of whom 391 were white and 11

were black. Atlantic Beach had 956 (921 white, 35 black). Jacksonville Beach had 5,943

people (5274 white, 669 blacks [11.3%] and there were another 779 white outside the city

limits.

The Polk City Directories of 1945 and 1948 identified African Americans as

“colored” by marking the head of the household with (c), giving us an idea of

who lived there. There are some problems with these and other directories. They did not

always have the names exactly right or they missed a few people. We cannot know how many

people lived at a specific address; usually the person perceived as the head of the

household had her/his name listed. Some people operated businesses from their homes.

Still, something is better than nothing and the data I have complied from them might give

a researcher or someone who is just curious valuable information. Here are the 126 entries

for Jacksonville Beach in the 1945 directory, organized by street. Where possible, I have

indicated whether the owner was on the premises except for churches and the Jacksonville

Beach Elementary School.

Jacksonville Beach 1945 |

|

|

|

|

|

Brown, Fletcher |

owner |

Lincoln Court 811 |

Simmons, Benjamin |

owner |

Lincoln Court 812 |

Bass, James |

rent |

Lincoln Court 818 |

Williams, Sallie E |

owner |

Lincoln Court 819 |

Williams, John H. |

rent |

Lincoln Court 820 |

Swan, Mary |

rent |

Shetter 612 |

Foster, Benjamin |

rent |

Shetter 614 |

Longwood, Martha |

rent |

Shetter 618 |

Tolson, Catherine |

rent |

Shetter 714 |

Little, William |

rent |

Shetter 718 |

Toomer, Nathan |

owner |

Shetter 722 |

Toney, John |

rent |

Shetter 726 |

Smith, Mose |

rent |

Shetter 732 |

Jackson, John |

rent |

Shetter 824 |

Collins, Charles |

owner |

1 Av S 503 |

Nelson, Jacob |

owner |

1 Av S 504 |

Poole, George |

owner |

1 Av S 607 |

Branch, Roosevelt restaurant |

|

1 Av S 613 |

Thomas, Estella |

rent |

1 Av S 615 |

Cain, Samuel billiards |

|

1 Av S 616 |

Day, Louise |

rent |

1 Av S 617 |

Hughes, Estelle |

rent |

1 Av S 623 |

Higginbotham, Gertrude |

owner |

1 Av S 630 |

Warden, Thomas |

rent |

1 Av S 636 |

Brooks, Floyd |

rent |

1 Av S 703 |

Brown, John L |

rent |

1 Av S 814 |

Weaver, Ray |

owner |

1 Av S 815 |

Dillard, Sylvester |

rent |

1 Av S 816 |

Gordon, Lewis |

rent |

1 Av S 825 |

Ferrell, Ollie |

rent |

1 Av S 836 |

Lane, Frank Rev |

rent |

1 Av S 911 |

Dillard, Jesse |

rent |

1 Av S 912 |

Linder, Jerry |

rent |

1 Av S 914 |

Kirkland, Mattie |

rent |

1 Av S 915 |

Davis, Samuel |

rent |

1 Av S 916 |

Carter, Walter |

rent |

1 Av S 919 |

Dillard, James |

rent |

1 Av S 920 |

Dillard, Leice |

rent |

1 Av S 923 |

Williams, Ida |

rent |

1 Av S 924 |

May, Adler |

rent |

1 Av S 930 |

Newsome, Villon |

rent |

1 Av s 935 |

Moore, Willard |

rent |

1 Av S 936 |

Thomas, Alvin |

owner |

2 Av S 508 |

Burroughs, James |

rent |

2 Av S 509 |

Burroughs, James |

rent |

2 Av S 530 |

McNeal, Robert J |

rent |

2 Av S 635 |

Aaron, Hattie |

rent |

2 Av S 635 |

Boyton, Arthur |

rent |

2 Av S 704 |

Nunnally, Van |

rent |

2 Av S 708 |

Jordan, Roxie |

rent |

2 Av S 716 |

Glover, Virginia |

rent |

2 Av S 719 |

McGahee, Julia |

rent |

2 Av S 734 |

Colquitt, Adele |

rent |

2 Av S 735 |

Douglas, Keith |

rent |

2 Av S 826 |

Leggett, Henry |

rent |

2 Av S 921 |

Harris, Claude |

owner |

2 Av S 922 |

Robinson, James |

rent |

2 Av S 923 |

Sims, Ezekiel |

rent |

2 Av S 929 |

Jones, John |

rent |

2 Av S 931 |

Sharp, Arrie |

rent |

2 Av S 935 |

Jackson, Henry |

rent |

2 Av S 936 |

Rice, Ivory |

owner |

3 Av S 635 |

Stafford, Sallie |

owner |

3 Av S 815 |

Robinson, Theodore |

owner |

3 Av S 823 |

Green, Joseph B. |

rent |

3 Av S 912 |

Drayton, Ernest |

rent |

3 Av S 915 |

Hunter, James P |

rent |

3 Av S 918 |

Thomas, Chester |

rent |

3 Av S 919 |

Sanctified Baptist Church |

|

3 Av S 921 |

Allen, Lamar |

owner |

3 Av S 923 |

Thomas, Charles T |

rent |

3 Av S 927 |

Allen, F. Renaldo |

owner |

4 Av N 529 |

King, Gardner |

rent |

4 Av N 537 |

Jackson, Henry |

rent |

4 Av N 603 |

Waiters Club |

|

4 Av N 637 |

Branch, Roosevelt |

rent |

4 Av N 639 |

First Baptist Church |

owner |

5 Av S 610 |

Robinson, Clifford |

rent |

5 Av S 612 |

Brooks, Robert |

rent |

6 St S 32 |

Rice, Charles |

rent |

6 St S 35 |

Martin, Rhoda |

rent |

6 St S 52 |

Watford, Roland |

owner |

6 St S 84 |

Hayward, Imogene |

owner |

6 St S 102 |

Jackson, Addie |

rent |

6 St S 105 |

Dixon, Luzene E [James, tailor] |

rent |

6 St S 106 |

Simmons, Alphonso O |

owner |

6 St S 121 |

Davis, James |

rent |

6 St S 122 |

Brewer, Beatrice |

rent |

6 St S 124 |

Williams, Frank |

rent |

6 St S 126 |

Hollis, Hattie |

rent |

6 St S 128 |

Thomas, Claude |

rent |

6 St S 130 |

Sneed, Maggie |

rent |

6 St S 131 |

Hines, John |

rent |

6 St S 202 |

Johnson, Alex |

rent |

6 St S 204 |

Hayes, Virginia |

rent |

6 St S 205 |

Durham, Mary |

rent |

6 St S 206 |

Brown, Hezekiah |

rent |

6 St S 215 |

Jones, James |

rent |

6 St S 221 |

Williams, Oscar |

rent |

6 St S 225 |

Murray, Grace |

rent |

6 St S 227 |

Troupe, Elijah |

rent |

6 St S 229 |

Wood, Joseph |

rent |

6 St S 230 |

Glover, Georgia M Mrs |

rent |

6 St S 231 |

Wood, Zack |

rent |

6 St S 306 |

Mitchell, Ruby |

rent |

6 St S 310 |

Walden, Mamie |

rent |

6 St S 320 |

Robinson, Vashti |

owner |

6 St S 408 |

St Andrews AME Church |

owner |

7 St S 200 |

Anthony, Sandy |

rent |

9 St S 70 |

Williams, Essie M |

rent |

9 St S 80 |

Vickers, Mary |

rent |

9 St S 87 |

Whitten, Curtis |

rent |

9 St S 102 |

Jordan, Robert |

rent |

9 St S 104 |

Bennefield, Louis |

rent |

9 St S 106 |

Hodges, Vassie |

rent |

9 St S 110 |

Caine, Walter |

owner |

9 St S 122 |

James,Clement |

rent |

9 St S 126 |

Terrell, Sandy |

owner |

9 St S 204 |

Cain, Samuel |

owner |

9 St S 210 |

Hollis, William |

rent |

9 St S 216 |

Harris Jack |

rent |

9 St S 226 |

Wilcher, Walter |

rent |

10 St S 71 |

Isch, John |

owner |

10 St S 104 |

Copeland, Caroline Mrs |

owner |

10 ST s 106 |

Lawson, William |

rent |

10 St S 121 |

Bennett, Trudie |

rent |

10 St S 125 |

Small, Samuel |

owner |

10 St S 132 |

Jax B Elementary (colored) |

|

10 St S 300 |

Most lived south of Beach Boulevard in an area known variously as “The Hill” or

“Pleasant Hill” and “Pepper Hill” and “Bloody Hill.” The

neighborhood was bounded by Beach Boulevard to the north, 3rd Street of state

highway A1A the to east , 10th Avenue South to the south, and 12th

Street South to West.

The area is flat as a pancake so the “hill” designation is a real puzzle.

“Bloody Hill” probably reflects a common view that whites held at the time that

“blacks” were inherently violent. Some lived north of Beach Boulevard on 4th

Avenue North in the third block west of 3rd Street North. This became a white

neighborhood because the Hamby Investment Company wanted to develop all the land westward

to Penman Road for white. The story is told in the student paper by Dianne Hagan,

“Beginnings of the Black Community in Jacksonville Beach.”

Click map for a larger image Click map for a larger image

1949 U. S. Geological Surver map

Dianne Hagan’s paper was submitted on December 5, 1975 as part of the requirements of

a junior-level history course, presumably at the University of North Florida; it is the

collection of the Beaches Area Historical Society. She says it is based on oral history

and indentifies the interviewees as James Dixon, an 82 year old African American tailor, Deacon Johnny

Brown and Blanche Brown, Phil Klein, Jacksonville Beach Fire Chief, a resident of the

beaches since 1929, Ed Smith, lumber company owner and memoirist of the beaches, Sue

Alexander, retired Fletcher librarian, Dotty Permenter, Rachael Cohen, daughter-in-law of

Pritchard, one of the developers of Ponte Vedra Beach, and Stanley Holtsinger. Dixon went

to Jacksonville Beach as a section hand for the Florida East Coast railroad. Dixon quoted

as saying that as many as 200 African American men employed by the big hotels during the

“season.” Those who worked in Mineral City (present-day Ponte Vedra Beach) lived

in Jacksonville Beach and traveled the few miles either on the railroad spur or by walking

along the beach when the tide was right. Many worked for the B. B. McCormick & Sons

Construction Company. McCormick’s headquarters and staging area abutted “The

Hill” and the company had quarters and a commissary for its African American workers.

The other African American neighborhood, commonly called “Pistol Hill” was

centered on 4th Avenue North. The City of Jacksonville Beach destroyed Pistol

Hill, the African American neighborhood north of then Hogan Road but now Beach Boulevard.

It contained privately-owned residences, apartments, and the Waiters’ Club, an

establishment for Negro men who worked at the Ponte Vedra Inn. When the Hamby Investment

Company wanted the land for whites, the City agreed to force the property owners

(including the white landlord, I. Silverberg) to sell their houses and property and to

accept equivalent property in “The Hill” so that Hamby could develop

“Pistol Hill” for whites. The process began in 1942 and lasted into 1948 but

most of the work was done by 1946. Part of the time was spent in improving “The

Hill” with a Negro Health Clinic, a recreation center, and paved streets. Land was

purchased and white residents near “The Hill” petitioned the City not to let

African Americans move too close to their neighborhood. On January 21, 1946, the City

Council accepted the estimate of $1,934.10 to extend fire protection in the Negro section.

Then the actual moving process began. On June 17, 1946, the Council agreed to pay $4,750

to the Woods-Hopkins Construction Company to move 11 dwellings, two garages, and one

garage apartment. Over a year later on November 3, 1947, the Council began discussion of

moving Waiters Club but then decided on June 28, 1948 to remove it. It was sold on July

12, 1948.

We know the names of some of the people (see list below) but we do not know what the

people forced out of their homes thought except it is hard to imagine any citizen loving

being evicted from his/her home. Perhaps letters or diaries written by the affected exist.

Without such materials, history cannot be written. History is based on concrete events

which we know from documents created by the participant or participants. Documents created

by non-participants are hearsay; those created decades later are dubious at best.

Allen, F. Renaldo |

owner |

4 Av N 529 |

King, Gardner |

rent |

4 Av N 537 |

Jackson, Henry |

rent |

4 Av N 603 |

Waiters Club |

|

4 Av N 637 |

Branch, Roosevelt |

rent |

4 Av N 639 |

African-Americans made progress in Atlantic Beach. Steve Piscitelli in his “Donner

Subdivision: The Rhythms of a Community sketches the history of the Donner neighborhood in

Atlantic Beach. In 1946, the Donner subdivision grew just off Mayport Road (see map

below). The subdivision was platted in 1921 and replatted in 1946 by E. H. Donner of

Jacksonville Beach. He was a European-American real estate developer who saw the

opportunity to earn a profit. The land sold for about $50 an acre but had no public

utilities. Donner deeded a lot for a playground in 1948. The people who lived there

created businesses. The Palmetto Garden was a restaurant, dance hall, and motel for

"blacks." There was also the Bluebird Nightclub. Tony’s Seafood Shack

served food but also had rooms on the second floor. Since motels and restaurants were

segregated, these businesses provided a real service. A list taken from the Polk City

Directory of 1945 shows that home ownership was very high among African Americans. (see

below). Because the Donner subdivision was two and one-half miles from the white

settlements of Atlantic Beach, the neighborhood had been able to grow too large to move

had the whites coveted their land. A Negro Chamber of Commerce was formed to promote

business. However, there were no public utilities when the area was being settled and they

were slow in being installed. But the Donner Subdivision provided a community for some of

the Beaches’ people. The Duval County school system constructed a school in 1939

1945 |

Status |

Street |

Houston, Robert |

tenant |

Donner Rd |

Jackson, Anderson |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Peterson, Edward |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Benton, Barney |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Dove, Jafford |

owner |

Donner Rd |

FIitzpatrick, John |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Dixon, Dora |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Koonce, Lex |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Wilson, Jesse |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Stanley, Julius |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Johnson, Richard |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Francis, Maggie |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Brown, Charles |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

George, Robert |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Brown, Henry |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Howell, Julius |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Howell, Maseo |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Upchurch, Fister |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Powell, Earl |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Mills, Robert B |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Warren, Norris |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Stuart, Robert |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Kennedy, Joseph |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Friendship Baptist Church |

|

Mayport Rd |

Liptrot, Jesse |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Christopher, Charles |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Morgan, Grant |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Smith, William |

tenant |

Mayport Rd |

Click map for larger image Click map for larger image

Donner Subdivision and Mayport Road, 1949

This 1949 U.S. Geological Survey map shows most of Atlantic Beach and its population

distribution. The tiny squares represent buildings, usually houses. One can see the

Atlantic Beach Hotel and its pier on the middle-left side. The African American population

lived in the Donner subdivision and on Mayport Road.

Racial segregation damaged all peoples, of course, since it was anti-free enterprise as

well as fairness but it hurt African-Americans more than other groups. Education made

little difference. Of the 95 African American teachers in Duval County in 1945-46, 91 of them

“holding the Bachelor’s degree and having maximum experience” received $189

a month, the minimum. By contrast, 71 of 83 white teachers in the same category received

$233 a month, 23.8% more. African American substitute teachers earned $4 a day whereas white

substitute teachers earned $5 a day, a 25% difference. The African-American schools in the

county also got left-over textbooks. Between high school and college, I worked a summer

job for the Coca-Cola Company in Jacksonville and saw this disparity when delivering

machines to public schools in Duval County. I also learned that African Americans and

summer help were only to get minimum wage no matter how competent or how much seniority

the employee had.

No wonder that African-Americans began suing for equal treatment after the Second World

War; after all they had sacrificed, bled, and died in a war against German and Japanese

racism. There were many successful lawsuits but the one that shook the nation was Brown v.

Topeka Board of Education in 1954 which ruled that segregation was inherently unequal and,

therefore, unconstitutional. At Fletcher Junior-Senior High School, one heard mutterings

that African-Americans would be killed and stuffed in lockers if they tried to integrate

the school. The “perfect” world was threatened. It was not the case that the

“whites” would not accept another race or a mixed-race person. After all, there

were students of Asian ancestry as well as people who were part American Indian.

Segregation was keeping "blacks," African Americans, in "their place,"

a place to which no Fletcher student aspired. Nothing happened for years in terms of

school integration but the civil rights movement picked up momentum in the early 1960s.

By 1948, the African American population in “The Hill” neighborhood increased

beyond the absorption of “Pistol Hill” as had its small business community. The

beaches and the Mayport Navy installation grew because of World War II and the beginning

of the Cold War but Jacksonville Beach had also improved the infrastructure of “The

Hill.” On April 3, 1944, Councilman B. B. McCormick proposed that the City pave two

through streets in “The Hill” neighborhood; the bill carried on September 18th.

One of the streets was 9th Street South which eventually dead ended at 16th

Avenue South. On April 21, 1946, the city manager was authorized to extend the sewer line

in the Hill and extend light and water utilities to the “Pistol Hill” transplant

site. Then, on February 17, 1947 officials proposed paving the streets in “The

Hill.” People demand goods and services so entrepreneurs opened hair care

establishments, restaurants, groceries, laundries, and so forth. More churches were

created. H. A. Prather, a prominent white businessman, built apartments in the

neighborhood. The Polk directory of 1948 is illustrative. In comparing the 1945 with the

1948 data one sees the same surname but a different first name. Why is unclear. The 1948

showed vacancies as well.

1948 |

Tenancy |

Street |

Vacant |

|

Lincoln Court 807 |

Brown, Fletcher |

owner |

Lincoln Court 811 |

Simmons, Benjamin |

owner |

Lincoln Court 812 |

Williams, Sallie E Mrs |

rent |

Lincoln Court 817 |

Butts, Robert |

rent |

Lincoln Court 818 |

Williams, John H. |

rent |

Lincoln Court 820 |

Robinson, Clifford restaurant |

rent |

Shetter 612 |

Foster, Benjamin |

rent |

Shetter 614 |

McIntyre, Ruby Mrs |

owner |

Shetter 618 |

Davis, Willie M Mrs |

rent |

Shetter 618 rear |

Little, William |

rent |

Shetter 718 |

Toomer, Nathan |

owner |

Shetter 722 |

Smith, Mose |

rent |

Shetter 732 |

Johnson, James |

rent |

Shetter 736 |

Bright, Isadore |

rent |

Shetter 816 |

Jackson, John |

rent |

Shetter 824 |

Gilbert, William |

rent |

Shetter 912 |

Armprester, Lillie M Mrs |

owner |

Shetter 914 |

McDonald, George |

owner |

Shetter 916 |

Howard, Flax Rev |

rent |

1 Av S 503 |

Nelson, Jacob |

rent |

1 Av S 504 |

Heyward, James |

rent |

1 Av S 507 |

Heyward, Katherine Beauty Shop |

rent |

1 Av S 507 |

Poole, George |

rent |

1 Ave S 611 |

Williams, Ernest |

rent |

1 Av S 613 |

Thomas, Estella Mrs |

rent |

1 Av S 615 |

King, Pearl Mrs. grocery |

rent |

1 Av S 616 |

Day, Louise |

rent |

1 Av S 617 |

King, Pearl Mrs. Restaurant |

rent |

1 Av S 618 |

Toomer, Joseph . barber |

rent |

1 Av S 625 |

Kites, Earl restaurant |

rent |

1 Av S 627 |

Branch, Emma Mrs. |

rent |

1 Av S 629 |

Goodwin, Rupert A |

rent |

1 Av S 630 |

Warden, Thomas |

rent |

1 Av S 636 |

Threats, Alton |

rent |

1 Av S 637 |

Collier, Eugene |

rent |

1 Av S 703 |

Sullivan, Eugene |

rent |

1 Av S 794 |

Brown, John L |

rent |

1 Av S 814 |

Weaver, Ray |

owner |

1 Av S 815 |

Batton, Susie Mrs. |

rent |

1 Av S 816 |

Smith, Roy grocery |

rent |

1 Av S 825 |

McLendon, Leo |

rent |

1 Av S 827 |

Brown, Jack |

rent |

1 Av S 829 |

Gordon, Lewis |

rent |

1 Av S 831 |

Ferrell, Ollie |

rent |

1 Av S 836 |

Lane, Frank Rev |

rent |

1 Av S 911 |

Dillard, Annie B. Mrs. |

rent |

1 Av S 912 |

Kirkland, Mattie Mrs. |

rent |

1 Av S 915 |

Davis, Ollie M Mrs. |

rent |

1 Av S 916 |

Saller [Salter] , Leon |

rent |

1 Av S 919 |

Davis, James |

rent |

1 Av S 920 |

Young, Maggie |

rent |

1 Av S 923 |

Williams, Ida Mrs. |

rent |

1 Av S 924 |

Dillard, Lois Mrs. |

rent |

1 Av S 930 |

Newsome, Guy Villon |

rent |

1 Av s 935 |

Moore, Willard |

rent |

1 Av S 936 |

Thomas, Bessie Mrs. |

owner |

2 Av S 508 |

James, Claremont |

rent |

2 Av S 509 |

Coleman, Henry |

rent |

2 Av S 610 |

Donaldson, Caesar |

rent |

2 Av S 612 |

Williams, Oscar |

owner |

2 Av S 614 |

Nunnally, Van |

rent |

2 Av S 708 |

Peoples, James |

rent |

2 Av S 716 |

Savage, Luventon |

rent |

2 Av S 717 |

vacant |

|

2 Av S 719 |

Chaney, William |

rent |

2 Av S 720 |

Jones, John |

rent |

2 Av S 731 |

Peoples, James |

rent |

2 Av S 734 |

Leverett, Janie M Mrs. |

rent |

2 Av S 738 |

Simmons, Wilbert |

rent |

2 Av S 911 |

Harris, Claude |

owner |

2 Av S 922 |

Sims, Ezekiel |

rent |

2 Av S 929 |

Sharp, Arrie [Ivory] |

rent |

2 Av S 935 |

Jackson, Henry |

rent |

2 Av S 936 |

Galloway, Lottie |

rent |

3 Av S 635 |

Prather Apartments |

|

3 Av S 700-712 |

Unit 1 |

|

|

Hampton, Gladys |

|

Apt 1 |

Harrison, Proffit |

|

Apt 2 |

Lawson, William |

|

Apt 3 |

Perry, Nellie B |

|

Apt 4 |

Ruff, Dorothy |

|

Apt 5 |

Robinson, William |

|

Apt 6 |

Lewis, Samel |

|

Apt 7 |

Powell, Jesse J |

|

Apt 8 |

Unit 2 |

|

|

Longwoods, Martha Mrs. |

|

Apt 1 |

Brown, Frank |

|

Apt 2 |

Moore, Thelma Mrs. |

|

Apt 3 |

James, Hutchie |

|

Apt 4 |

Green, Joseph B |

|

Apt 5 |

Rountree, Macie |

|

Apt 6 |

Robinson, Raymond |

|

Apt 7 |

Unit 3 |

|

|

Copeland, Ulysses |

|

Apt 1 |

Smith, Edith Mrs. |

|

Apt 2 |

Unit 4 |

|

|

Hagans, Dory |

|

Apt 1 |

Weaver, William |

|

Apt 2 |

Burke, Thomas |

|

Apt 3 |

Banks, William |

|

Apt 4 |

Burroughs, James B |

|

Apt 5 |

Ikry, Hilliard |

|

Apt 6 |

Benson, James |

|

Apt 7 |

Second Baptist Church |

|

corner 8th S |

First Baptist Church |

|

3 Av S 800 |

Stafford, Sallie Mrs. |

owner |

3 Av S 815 |

Rice, Ivory |

|

3 Av S 820 |

under construction |

|

3 Av S 821 |

Robinson, Theodore |

owner |

3 Av S 823 |

Kirkland, Leander |

owner |

3 Av S 911 |

Collins, Nellie Mrs. |

rent |

3 Av S 912 |

Drayton, Ernest |

rent |

3 Av S 915 |

Bennett, Robert L |

rent |

3 Av S 916 |

Refoe, Charles |

rent |

3 Av S 918 |

Refoe, Charles |

rent |

3 Av S 918 |

Allen, Lamar |

owner |

3 Av S 923 |

Thomas, Charles T Rev |

rent |

3 Av S 927 |

Church of God by Faith |

|

3 Ave S 931 |

Allen, Lottie Mrs. |

rent |

4 Av S 412 |

Williams, Robert |

rent |

4 Av s 737 |

Gillmore, Stella Mrs. |

rent |

4 Av S 808 |

Edwards, Matilda Mrs. |

owner |

4 Av S 826 |

Smith, Robert J |

owner |

4 Av S 830 |

Simmons, Lillian Mrs. |

rent |

4 Av S 830 rear |

Waller, James |

rent |

4 Av S 904 |

Harvey, Joseph |

rent |

4 Ave S 908 |

Bennett, Fulcher |

rent |

4 Av S 912 |

Miles, Henry |

rent |

4 Av S 914 |

Bell, Simeon |

rent |

4 Av S 916 |

Ellis, Nathan |

rent |

4 Av S 985 |

Vickers, Charles V |

rent |

5 Av S 601 |

Robinson, Clifford |

rent |

5 Av S 612 |

Jackson, Celie |

rent |

6 St S 32 |

vacant |

|

6 St S 35 |

Gatsin, Richard |

rent |

6 St S 51 |

Martin, Carrie M |

owner |

6 St S 52 |

Davis Evergreen Restaurant |

|

6 St S 74 |

Watford, Sarah Mrs. |

owner |

6 St S 84 |

Gilford, Julius [white] |

rent |

6 St S 115 |

Jackson, Addie Mrs |

rent |

6 St S 117 |

Hayward, Lillie |

owner |

6 St S 118 |

Dixon, Luzene E clothes clean |

rent |

6 St S 120 |

Simmons, Alphonso O |

owner |

6 St S 121 |

Hartsfield, Bernice Mrs. |

rent |

6 St S 122 |

Brewer, Beatrice Mrs. |

rent |

6 St S 124 |

Williams, Frank |

rent |

6 St S 126 |

Hollis, Hattie Mrs. |

rent |

6 St S 128 |

Sneed, Maggie Mrs. |

rent |

6 St S 129 |

vacant |

|

|

Burroughs, Susie Mrs. |

rent |

6 St S 205 |

Murray, Grace M Mrs. |

rent |

6 St S 211 |

vacant |

rent |

6 St S 212 a |

Caine, Isaiah |

rent |

6 St S 212 b |

Bell, Henry |

rent |

6 St S 215 |

Coleman, James |

rent |

6 St S 221 |

Williams, Bonnie |

rent |

6 St S 225 |

Josey, William |

rent |

6 St S 227 |

Brown, Hezekiah |

rent |

6 St S 229 |

Day, Ellis |

rent |

6 St S 230 |

Glover, Georgia M Mrs. |

rent |

6 St S 231 |

vacant |

|

6 St S 304 |

vacant |

|

6 St S 306 |

vacant |

|

6 St S 308 |

Walden, Mamie Mrs. |

owner |

6 St S 332 |

Robinson, Vashti |

owner |

6 St S 408 |

St Andrews AME Church |

owner |

7 St S 200 |

Jackson, Ethel |

rent |

8 St S 35 |

Harris, Quitman |

owner |

8 St S 52 |

Allen, Lottie Mrs. |

rent |

8 St S 420 |

Smith, Edward |

rent |

9 St S 70 |

Jackson, Walter |

rent |

9 St S 80 |

Kirkland, Ralph |

rent |

9 St S 84 |

Vickers, Mary Mrs. |

rent |

9 St S 87 |

Coleman, Edward |

rent |

9 St S 102 |

Russell, Charles |

rent |

9 St S 104 |

Taylor, June |

rent |

9 St S 106 |

Williams, John W |

rent |

9 St S 108 |

Hollis, Alice Mrs. |

rent |

9 St S 110 |

Caine, Walter |

owner |

9 St S 122 |

Correlus, Golden |

rent |

9 St S 126 |

Moore, Henry |

rent |

9 St S 130 |

Terrell, Sandy |

owner |

9 St S 204 |

Kirkland, Gus |

rent |

9 St S 205 |

Cross, Jesse J |

rent |

9 St S 205 rear |

Cain, Samuel |

owner |

9 St S 210 |

Warren, Preston |

rent |

9 St S 210 |

Jackson, Curtis |

rent |

9 St S 216 |

Bass, James |

rent |

9 St S 226 |

Shafter, Leroy |

rent |

9 St S 411 |

Verner, James |

rent |

10 St S 71 |

Copeland, Caroline Mrs. |

owner |

10 St S 106 |

vacant |

|

10 St S 106 rear |

Isaiah, John |

rent |

10 St S 110 |

Hilton, Mamie Mrs. |

rent |

10 St S 120 |

Hughes, Stella Mrs. |

owner |

10 St S 121 |

Bennett, Trudie |

rent |

10 St S 125 |

Small, Samuel |

owner |

10 St S 132 |

Kirkland, Lee |

owner |

10 St S 200 |

Jax Bch Elementary colored |

|

10 St S 300 |

McNeill, Robert Jaboe |

owner |

10 St S 400 |

Graham, Oscar |

rent |

Beach Blvd sw of Penman |

Rountree, English |

rent |

Beach Blvd sw of Penman |

The Atlantic Beach data for 1948 showed population growth but it also showed five women

living in the white section. There were live-in servants no doubt. The percentage of

ownership was very high.

1948 |

Tenancy |

Street |

Williams, Anna L |

Gaines servant |

Beach Av 697 rear |

Cuthbert, Letha |

Blondheim servant |

Beach Av 1174 rear |

Simmons, Willie M |

Rosborough servant |

Beach Ave 1433 rear |

Muller, Alberta |

Tucker servant |

Beach Ave 1451 rear |

Anderson, Katie M. Mrs. |

Kavanaugh servant |

Beach Av 1689 rear |

Johnson, Minnie L Mrs |

rent |

Donner Rd |

Jackson, Anderson |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Stewart, Robert Jr |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Benton, Bonnie |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Dove, Jafford |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Williams, George |

owner |

Donner Rd |

Brown, Thomas |

owner |

Dudley St |

Griffin, Ollie Mrs. |

owner |

Dudley St |

Hicks, Albert |

rent |

Dudley St |

Howell, Julius |

owner |

Dudley St |

Howell, Maseo |

owner |

Dudley St |

Jenny, Ruby Mrs. |

owner |

Dudley St |

Pierce, Roberta Mrs. |

rent |

Dudley St |

Stewart, Robert |

owner |

Dudley St |

Davis, Ernest |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Wade, Frank |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Hand, Charles D |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Scott, Allen L Rev |

rent |

Mayport Rd |

Stanley, Julius |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Wade, John H |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

Friendship Baptist Ch |

owner |

Mayport Rd |

George, Robert |

owner |

Robert St |

Holmes, James |

owner |

Robert St |

Liptrot, Jesse |

owner |

Robert St |

One solution to the attendance problem at the beach was to hire some African American players but

that was not to be. Hank Aaron said that the Birds tried to put African American players on the team

but the local chamber of commerce said no. Herb Shelley, Secretary of the Chamber, said

“No race is involved in it. It’s just that patrons of the team felt they would

rather have an all-white team.” City officials and the American Legion also opposed

such a move.[4]

What happened to the baseball facilities? City Manager Wilson Wingate worked with Joe

O'Toole of the Pittsburgh Pirate organization to locate the Pirates’ minor league

training facilities in Jacksonville. Beach.[5]

The city built four baseball diamonds just south of the Jacksonville Beach baseball

stadium. Seventeen teams trained between 1957 and 1961. In 1957, the Beaumont Texas

Pirates of the Class B Big State League, the Clinton Iowa Pirates of the Class D Midwest

League, the Columbus Ohio Jets of the Class AAA International League, the Grand Forks,

North Dakota Chiefs of the Class C Northern League, the Jamestown, New York Falcons of the

Class D New York-Pennsylvania League, and the Lincoln, Nebraska Chiefs of the Class A

Western League. Clinton, Columbus, Grand Forks, and Lincoln were joined in 1958 by the

Salt Lake City, Utah Bees of the Class AAA Pacific Coast League and the San Angelo, Texas

Pirates of the Class C Sophomore League. In 1959, Columbus, Grand Forks, Lincoln, Salt

Lake City, and San Angelo were joined by the Class D Dubuque, Iowa Pirates of the Midwest

League, the Idaho Falls, Idaho Russets of the Class C Pioneer League, the Wilson, North

Carolina Tobs of the Class B Carolina League, and the Columbus, Georgia Pirates of the

Class A South Atlantic League. Columbus, Grand Forks, Lincoln, Salt Lake City, San Angelo,

and Dubuque were joined in 1960 by the Asheville, North Carolina Tourists of the Class A

South Atlantic League, the Burlington, Iowa Bees of the Class B Illinois-Iowa-Illinois

League, the Hobbs, New Mexico Pirates of the Class D Sophomore League, and the Savannah,

Georgia Pirates of the Class A South Atlantic League. In the last year, 1961, only four

teams trained there: Asheville, Burlington, Hobbs, and the Batavia, New York Pirates of

the Class D New York-Pennsylvania League.

These teams included African American players to the beach. The Beaches were not

hospitable to African Americans so there were no facilities available for the black minor

league baseball players at the beaches. Wingate’s son, Ron, remembers hearing

discussions regarding this problem. Housing was accomplished by farming them out to

“The Hill,” an African American section of Jacksonville Beach a few blocks east of the

station. Strickland’s Restaurant, a very popular eatery more than a mile north, added

a back room in which African Americans could eat and be served by fellow African

Americans.[6]

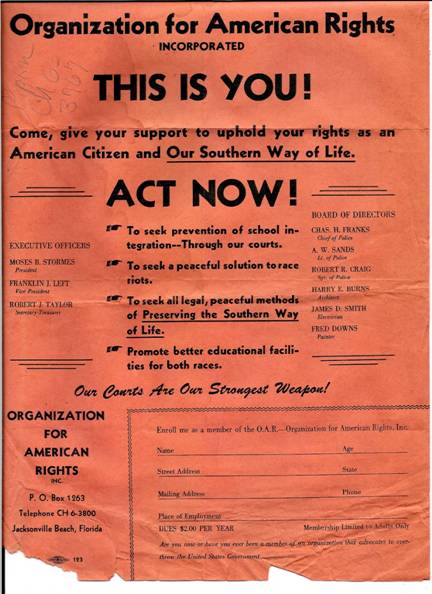

In my very lengthy essay, Carnival

on the Boardwalk, I told the story of anti-black efforts at the beaches led by a

Jacksonville Beach city councilman. When an uproar occurred in 1960, other city councilmen

and beach leaders disavowed the Organization for American Rights, as the organization

called itself. Local African Americans must have wondered about this. On April 27, 1958,

conservative terrorists bombed the James Weldon Junior High School, a Negro school in

Jacksonville, and a synagogue and Jewish community center. There was only minor damage;

the terrorist were only mildly terrorizing. These barbarous acts drew the condemnation of

many, including Hazel Brannon Smith, a small-town Mississippi newspaper editor.

The Civil Rights movement finally came to the beaches although it had been active in

Jacksonville where it had been met by violence when Rutledge Pearson led demonstrations in

August, 1960 against segregated lunch counters at the downtown Woolworth's, McCrorys, and

Kress stores. One day, two African American youths accidentally knocked a white woman into a plate

glass window. Then on another day two women got into a fight. On August 27th, hundreds of

Klansmen and other bigots demonstrated in downtown Jacksonville with the police watching.

When some young African Americans tried to get lunch counter service at the Grant's store

and were refused, they were attacked by the white demonstrators who used ax handles and

other weapons. They chased the teenagers into an African American section of town but were run out by

an African Americangang. Police intervention stopped the riot. More "blacks" than

"whites" were arrested, of course.

The city government of Haydon Burns, even though African-American votes put him in office,

was racist. He was a powerful force in Jacksonville affairs as mayor from 1949-1965, when

he became governor. Burns was a segregationist so he refused to create a biracial

commission to resolve the issues. He was a determined conservative mayor of a conservative

city. African-Americans threatened an economic boycott and white businessmen, fearing loss

of profits, agreed to meet with African-American leaders and work out compromises.

Desegregation began. "Green" was a more powerful color than white and

"black."

Jacksonville had a large African American population, potential customers for the

boardwalk; it had once been a majority African American city but annexations of suburbs changed that.

In 1960, the city of 372,569 was 26.9% African American (100,169 persons); the Standard

Metropolitan Statistical Area population was 455,411 was 23.2% African American (105,843

persons). However, the tradition of racial segregation meant that Beach business owner did

not want the patronage of a quarter of the population of the county. This was not a Duval

County phenomenon; racial bigotry was common throughout the United States.

Not many African Americans, either in absolute numbers or as a percentage of the total

population lived on the beaches and the periodic influx of white tourists, civilian or

military, shrank both numbers. The 1960 Census is instructive. Of the 12,049 persons

living in Jacksonville Beach, 1,111 (9.2%) were African American; since Jacksonville

provided most of the jobs at the beaches, it is not surprising. Atlantic Beach, a

wealthier community of 3,125 persons, was home to 605 (19.4%) African Americans. The high

percentage surely reflects the legacy of the fishing and U. S. Naval industries of

Mayport, the Atlantic Beach Hotel, and the Florida East Coast Railway. Neptune Beach has

three African Americans out of a population of 2,868., probably live-in servants.

The Census also had Division categories. The Jacksonville Beach Division of Duval County

(covering more than the political boundaries) had 23,823 of whom 2,366 (9.9%) persons were

African American. Palm Valley and Ponte Vedra Beach were small, unincorporated areas of

the Northern St. Johns County Division, an area larger than these two tiny communities.

This Division contained 5,020 persons of whom 391 (7.8%) were African Americans. Ponte

Vedra Beach had been founded as an upper-income, private settlement and it was exclusive

and wealthy.[7]

There were so few African Americans at the beaches and the adults were so well known meant

that retaliation for any efforts to acquire access to the public beaches or to use the

public accommodations of the boardwalk seemed highly likely. Councilman Moses Stormes,

President of the newly-chartered Organization of American Rights, Inc., Franklin J. Left,

Vice President , and Robert J. Taylor, Secretary Treasurer, were its officers; the Board

of Directors included Chuck Franks, Chief of the Jacksonville Beach Police, A. W. Sands,

Lieutenant of Police, Robert R. Craig, Sergeant of Police, Harry E. Burns, architect,

James D. Smith, electrician, and Fred Downs, painter. The OAR sent a scurrilous letter in

the Fall of 1960 saying that integration meant African Americans (the letter used a

different word) would be raping white girls and other similar comments. It also issue a

membership recruitment flyer (pictured). The members position on race and segregation was

clear; it was to be maintained at all costs.

The OAR leaders went too far and most had to repudiate the letter and resign from the OAR.

Left, Franks, Sands, Craig, and Downs resigned. Burns said he was never a member and

condemned the letter. Taylor admitted that some of the language was objectionable and then

resigned. Stormes, on the other hand, defended the letter. At a Council meeting in

October, two different citizens rose to demand that Stormes resign. The Council members

ignored them, perhaps indicating that they were segregationists.[8]

OAR Flyer Source: Austin Smith

The views of Stormes and his ilk did not reflect the views of others or, perhaps, others

were practical. In my research in beaches newspapers, I found nothing about desegregation.

My sense is that the local media cooperated to keep it from being an issue. The available

accounts differ but the essential facts are the same.

Contemporaries described the events in an oral history session recorded at the Beaches

Area Historical Society and Museum in Jacksonville Beach in early 2007. They noted that

the integration drove whites away from the boardwalk but there was no violence. Because of

the danger of retaliation, the 1,111 Jacksonville Beach African Americans tended not to

pioneer. White tourists had come from north Florida towns as well as Georgia; the Chamber

of Commerce had done everything it could to promote it. However, they expected a

whites-only situation. With the beach and boardwalk being opened to all, many whites

stayed away. Martin G. Williams, Jr. in a message to the author in June, 2009 believed

that the boardwalk as he knew was dying in the 1960’s for several reasons. Many

blamed integration in 1961 or 1962, a difficult situation that Mayor Justin Montgomery

handled very well. Bus loads of African Americans were brought to the Beach and Boardwalk by the

NAACP. White families stayed away. By 1970, the number of rides and amusements were sparse

because business had declined. He noted “there was much competition from Daytona

Beach, Myrtle Beach, Panama Beach, other vacation attractions and travel had gotten much

easier. Disney and the Mouse arrived in Orlando, air conditioned hotels were common and

golf and boating had become very popular. The family visitors from South Carolina, Georgia

and Alabama were gone.”[9]

A quite different view emerges from an anonymous typed document possessed by the Beaches

Area Historical Society, the view that civic leaders were progressive and quietly took the

lead to achieve integration. This six-page document is unsigned and undated although may

have been written in the late 1960s. It says the true story of what happened was revealed

to a reporter of The Beaches Leader and that a member of the “black

community” wanted it known. Some fifteen years before this essay was written, the

City Council completed the Carver Recreation Center and swimming pool and began tackling

the problem of substandard housing in 1955 in the African American section of town called

“the Hill.” It took five years to complete the application process and begin

construction but the City demonstrated that the government was not just for whites. They

had integrated the city golf course, built 1963, without incident and it turned a huge

profit in 1965.

In 1963, the mayor, W. S. Wilson, the City Council, and City Manager and other civic

leaders such as Justin C. Montgomery, a former mayor and nephew a former mayor and city

councilman, , decided that the time for change had come. They did not want the violence

they had seen in Jacksonville or the demonstrations occurring in St Augustine in 1964

under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. They desegregated the beach or

waterfront by quietly arranging for African American sailors, dressed in civilian clothes,

to drive onto the strand on a busy Saturday afternoon and go into the surf. Law

enforcement officers were hidden but acted quickly to disperse any hostile crowds. They

would use the tactic of a fait accompli to desegregate further.

Before the Civil Rights Act of July 4, 1964 was passed Jacksonville Beach had desegregated

its public accommodations. The Council asked the Chamber of Commerce to meet with local

motel and restaurant owners and ask them to desegregate; ninety percent complied. On early

June, 1969, the Chamber cooperated to desegregate the bars.[10]

Desegregation occurred in other important ways. African American citizens were not allowed

at City Council meetings. Instead, the City Council came to them at the Carver Center. In

Spring, 1965, at an outdoor ceremony for Beaches Welcome Day, invited groups were

announced, applauded, and seat on the platform. Then came the group of African American

invitees. They were announced, vigorously applauded and seated. The local high school, Duncan U. Fletcher, desegregate in 1967 without fuss.

Had not national policy and practice changed, whether Jacksonville Beach and its

entertainment industry cannot be known. Certainly respect for the law and a more tolerant

attitude in a resort community made a difference. Increasing dependence on the Navy at

Mayport surely did. The armed forces had desegregated decades before. As the naval base at

Mayport grew, its sailors had to have recreational place.